The Atlantic Return and the Payback of Evangelization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROUND the BEND TEAM Being Through Our Efforts

Round the bend Farm A CENTER FOR RESTORATIVE COMMUNITY 1 LETTER FROM THE It’s been an AMAZING monarch year for us here at RTB. We even offered CO-VISIONARIES a monarch class in July Desa & Nia Van Laarhoven and we’ve been hatching & Geoff Kinder some at RTB to increase s fall descends on Round the Bend Farm their odds. (RTB), vivid colors mark the passage of time. Autumn’s return grounds us amid Aeach day’s frenetic news cycles. It reminds us of the deeper cycle that connects us all to the earth and to each other. And yet one news story, from late September, has done the same. More than 7.5 million people came together in cities and villages across the planet to call in unison for an environmentally just and sustainable world. This is a story that speaks to RTB’s mission and purpose and demonstrates the concept of Restorative Community that’s so central to our existence. You can see it in the image that juxtaposed September’s global crowds with the prior year’s solitary Swedish protester. You can hear it in the words spoken by an Indigenous Brazilian teen to 250,000 people lining the streets of New York City. Restorative Community is a force multiplier for our own personal commitments to justice, health and peace. It nurtures and supports us as individuals, unites and strengthens us as a movement and harnesses our differences in service of our common goals. In community, we respect, enjoy and learn from each other. As you page through this year’s annual report, we hope you experience the same! We’re This past year, we continued to expand our inspired and encouraged by what we’ve Restorative Community at RTB, more than accomplished this year and we’re honored to doubling the number of people who visited serve our community in ever new ways. -

Unintended Consequences of the American Presidential Selection System

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLP\15-1\HLP104.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-JUL-21 12:54 The Best Laid Plans: Unintended Consequences of the American Presidential Selection System Samuel S.-H. Wang and Jacob S. Canter* The mechanism for selecting the President of the United States, the Electoral College, causes outcomes that weaken American democracy and that the delegates at the Constitu- tional Convention never intended. The core selection process described in Article II, Section 1 was hastily drawn in the final days of the Convention based on compromises made originally to benefit slave-owning states and states with smaller populations. The system was also drafted to have electors deliberate and then choose the President in an age when travel and news took weeks or longer to cross the new country. In the four decades after ratification, the Electoral College was modified further to reach its current form, which includes most states using a winner-take-all method to allocate electors. The original needs this system was designed to address have now disappeared. But the persistence of these Electoral College mechanisms still causes severe unanticipated problems, including (1) con- tradictions between the electoral vote winner and national popular vote winner, (2) a “battleground state” phenomenon where all but a handful of states are safe for one political party or the other, (3) representational and policy benefits that citizens in only some states receive, (4) a decrease in the political power of non-battleground demographic groups, and (5) vulnerability of elections to interference. These outcomes will not go away without intervention. -

Next-Gen Technology Transformation in Financial Services

April 2020 Next-gen Technology transformation in Financial Services Introduction Financial Services technology is currently in the midst of a profound transformation, as CIOs and their teams prepare to embrace the next major phase of digital transformation. The challenge they face is significant: in a competitive environment of rising cost pressures, where rapid action and response is imperative, financial institutions must modernize their technology function to support expanded digitization of both the front and back ends of their businesses. Furthermore, the current COVID-19 situation is putting immense pressure on technology capabilities (e.g., remote working, new cyber-security threats) and requires CIOs to anticipate and prepare for the “next normal” (e.g., accelerated shift to digital channels). Most major financial institutions are well aware of the imperative for action and have embarked on the necessary transformation. However, it is early days—based on our experience, most are only at the beginning of their journey. And in addition to the pressures mentioned above, many are facing challenges in terms of funding, complexity, and talent availability. This collection of articles—gathered from our recent publishing on the theme of financial services technology—is intended to serve as a roadmap for executives tasked with ramping up technology innovation, increasing tech productivity, and modernizing their platforms. The articles are organized into three major themes: 1. Reimagine the role of technology to be a business and innovation partner 2. Reinvent technology delivery to drive a step change in productivity and speed 3. Future-proof the foundation by building flexible and secure platforms The pace of change in financial services technology—as with technology more broadly—leaves very little time for leaders to respond. -

Sustainability Guidebook

SUSTAINABILITY GUIDEBOOK ©LEVI STRAUSS & CO. | December 2013 | Sustainability Guidebook Table of Contents Introduction Ratings defined Chapter One – Labor Standards 1. Child Labor 2. Prison Labor/Forced Labor 3. Disciplinary Practices 4. Legal Requirements 5. Ethical Standards 6. Working Hours 7. Wages and Benefits 8. General Labor Practices and Freedom of Association 9. Discrimination 10. Community Involvement 11. Foreign Migrant Labor 12. Dormitories 13. Permits Chapter Two – Environment, Health & Safety Part I : Safety Guidelines 1. Safety Committees 2. Risk Assessment 3. Emergency Preparedness 4. Building Integrity 5. Aisles and Exits 6. Lighting 7. Housekeeping 8. Electrical Safety 9. Control of Hazardous Energy/Lock‐Out/Tag‐Out 10. Machine Guarding 11. Powered Industrial Trucks 12. Noise Management 13. Personal Protective Equipment 14. Ventilation 15. Chemical Management 16. Extreme Temperatures 17. Asbestos Management 18. Occupational Exposure Limits 19. Signs and Labels 20. Maintenance Part II : Finishing Guidelines 1. Finishing Safety Guidelines 2. Hand Scraping 3. Laser Etching 4. Resin/Curing 5. Screen Printing 6. Spraying 7. Abrasive Blasting 8. Ozone Part III : Health Guidelines 1. First Aid 2. Preventing Communicable Disease Part IV : Environment Guidelines 1. Global Effluent Requirements 2. Domestic Wastewater Requirements 3. Biosolids Management 4. Waste Management 2.1 Transporting Hazardous Materials 2.2 Hazardous Waste Management 2.3 Solid Waste Management 5. Preventing Storm Water Pollution 6. Aboveground/Underground Storage ©LEVI STRAUSS & CO. | December 2013 | Sustainability Guidebook | Table of contents | page 1 Appendix A : SAFETY GUIDELINES 1. Safety Committees 2. Emergency Preparedness 3. Aisles and Exits 4. Housekeeping Checklist 5. Electrical Safety Inspection Checklist 6. Lock‐Out/Tag‐Out 7. -

The Popular Culture Studies Journal

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor Kevin Calcamp Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Wrestling” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of https://openclipart.org EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH FALON DEIMLER Minnesota State University, Moorhead University of Wisconsin-Madison JESSICA AUSTIN HANNAH DODD Anglia Ruskin University The Ohio State University AARON BARLOW ASHLEY M. DONNELLY New York City College of Technology (CUNY) Ball State University Faculty Editor, Academe, the magazine of the AAUP JOSEF BENSON LEIGH H. EDWARDS University of Wisconsin Parkside Florida State University PAUL BOOTH VICTOR EVANS DePaul University Seattle University GARY BURNS JUSTIN GARCIA Northern Illinois University Millersville University KELLI S. BURNS ALEXANDRA GARNER University of South Florida Bowling Green State University ANNE M. CANAVAN MATTHEW HALE Salt Lake Community College Indiana University, Bloomington ERIN MAE CLARK NICOLE HAMMOND Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota University of California, Santa Cruz BRIAN COGAN ART HERBIG Molloy College Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne JARED JOHNSON ANDREW F. HERRMANN Thiel College East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO MATTHEW NICOSIA Maryville University of St. -

CHP As a Boiler Replacement At

Andy Colwell AnnMarie Mountz Penn State is a World Class University with more than 50,000 students, faculty and staff on campus on any given day. As a provider of utilities, Steam Services plays an important supporting role in the success of the University’s mission of teaching, research and service. 3/19/10 2 • Buildings Served • +40 Operations and • +700 total Maintenance Staff • +200 served with steam Power Plants • +19 million ft2 18 Operators 8 daylight maintenance • +10 engineering and 6 Coal and Ash handlers technical support 2 supervisors Distribution 7 Daylight Maintenance 1 supervisor 2 Staff Assistants 4/30/2013 3/19/10 3 4/30/2013 3/19/10 4 Additional Steam Capacity • Steam demands began to exceed firm capacity Aging Infrastructure • Last steam capacity upgrade was 1971 Essential Services • Where/How to care for 10,000+ folks during a total loss of power to campus • Estimated we need 12 mW to do this 4/30/2013 3/19/10 5 4/30/2013 3/19/10 6 4/30/2013 3/19/10 7 exhaust Steam to campus 32 kpph un-fired 117,000 kpph fired RENTEC HRSG 900 oF Natural gas or oil Combustor 7mW SOLAR TAURUS 70 air 4/30/2013 3/19/10 8 Combustion Turbine $3.9 million HRSG $1.4 million Total Project $19 million 4/30/2013 3/19/10 9 Covers • Planned in-service and out-of-service maintenance • Service calls • Complete overhaul after 30,000 hours Costs • $21,000/month, $35 per hour • ~$600,000 per year 4/30/2013 10 3/19/10 Before ECSP Upgrades Electricity After ECSP CHP Prior to 2011 Generated After 2011 (kWh) Electricity 4% Generated (kWh) -

Environmental Standards, Thresholds, and the Next Battleground of Climate Change Regulations

Article Environmental Standards, Thresholds, and the Next Battleground of Climate Change Regulations Kimberly M. Castle† and Richard L. Revesz†† Introduction .......................................................................... 1350 I. Traditional Risk Assessment Models ............................. 1363 A. Carcinogens ............................................................... 1363 B. Noncarcinogens Other than Criteria Pollutants ..... 1371 II. Treatment of Criteria Pollutants ................................... 1377 A. Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 ......................... 1378 B. Shift in the EPA’s Approach: A Case Study of Lead ....................................................................... 1383 C. Rejecting Thresholds and Calculating Benefits Below the NAAQS .................................................... 1391 III. Calculating Health Benefits from Particulate Matter Reductions Below the NAAQS ....................................... 1397 A. Scientific Basis .......................................................... 1400 B. Regulatory Treatment .............................................. 1409 C. Addressing Uncertainty ........................................... 1413 D. Adjusting Baselines .................................................. 1417 IV. Considering Co-Benefits ................................................. 1421 A. Co-Benefits and Indirect Costs ................................ 1424 B. The EPA’s Practice ................................................... 1427 † Research Scholar, Institute -

Neutral Ground Or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston American Studies Faculty Publication Series American Studies 2018 Neutral Ground or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter Lynnell L. Thomas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/amst_faculty_pubs Part of the African American Studies Commons, Africana Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, and the Tourism Commons Neutral Ground or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter Lynnell L. Thomas The National Slave Ship Museum will be the next great attraction for visitors and locals to experience. It will reconnect Americans to their complicated and rich history and provide a neutral ground for all of us to examine the costs of our country’s development. —LaToya Cantrell, New Orleans councilmember, 20151 In 2017, the city of New Orleans removed four monuments that paid homage to the city’s Confederate past. The removal came after contentious public de- bate and decades of intermittent grassroots protests. Despite the public process, details about the removal were closely guarded in the wake of death threats, vandalism, lawsuits, and organized resistance by monument supporters. Work- Lynnell L. Thomas is Associate Professor of American Studies at University of Massachusetts Boston. Research for this article was made possible by a grant from the College of the Liberal Arts Dean’s Research Fund, University of Massachusetts Boston. I would also like to thank Leon Waters for agreeing to be interviewed for this article. 1. In 2017, Cantrell was elected mayor of New Orleans; see “LaToya Cantrell Elected New Or- leans’ First Female Mayor,” http://www.nola.com/elections/index.ssf/2017/11/latoya_cantrell _elected_new_or.html. -

GENERAL ASSEMBLY of NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2013 S 2 SENATE BILL 744 Appropriations/Base Budget Committee Substitute Adopted 5/29

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2013 S 2 SENATE BILL 744 Appropriations/Base Budget Committee Substitute Adopted 5/29/14 Finance Committee Substitute Adopted 5/29/14 Pensions & Retirement and Aging Committee Substitute Adopted 5/29/14 Short Title: Appropriations Act of 2014. (Public) Sponsors: Referred to: May 15, 2014 1 A BILL TO BE ENTITLED 2 AN ACT TO MODIFY THE CURRENT OPERATIONS AND CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS 3 APPROPRIATIONS ACT OF 2013 AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES. 4 5 The General Assembly of North Carolina enacts: 6 7 PART I. INTRODUCTION AND TITLE OF ACT 8 9 TITLE OF ACT 10 SECTION 1.1. This act shall be known as "The Current Operations and Capital 11 Improvements Appropriations Act of 2014." 12 13 INTRODUCTION 14 SECTION 1.2. The appropriations made in this act are for maximum amounts 15 necessary to provide the services and accomplish the purposes described in the budget. Savings 16 shall be effected where the total amounts appropriated are not required to perform these 17 services and accomplish these purposes and, except as allowed by the State Budget Act, or this 18 act, the savings shall revert to the appropriate fund at the end of each fiscal year as provided in 19 G.S. 143C-1-2(b). 20 21 PART II. CURRENT OPERATIONS AND EXPANSION GENERAL FUND 22 23 CURRENT OPERATIONS AND EXPANSION/GENERAL FUND 24 SECTION 2.1. Appropriations from the General Fund of the State for the 25 maintenance of the State departments, institutions, and agencies, and for other purposes as 26 enumerated, are adjusted for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2015, according to the schedule 27 that follows. -

Funding Report

PROGRAMS I STATE CASH FLOW * R FED CASH FLOW * COMPARE REPORT U INTRASTATE * LOOPS * UNFUNDED * FEASIBILITY * DIVISION 7 TYPE OF WORK / ESTIMATED COST IN THOUSANDS / PROJECT BREAK TOTAL PRIOR STATE TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM PROJ YEARS 5 YEAR WORK PROGRAM DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRAM "UNFUNDED" LOCATION / DESCRIPTION COST COST FUNDING ID (LENGTH) ROUTE/CITY COUNTY NUMBER (THOU) (THOU) SOURCE FY 2009 FY 2010 FY 2011 FY 2012 FY 2013 FY 2014 FY 2015 FY 2016 FY 2017 FY 2018 FY 2019 FY 2020 FUTURE YEARS 2011-2020 Draft TIP (August 2010) I-40/85 ALAMANCE I-4714 NC 49 (MILE POST 145) TO NC 54 (MILE 7551 7551 IMPM CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 POST 148). MILL AND RESURFACE. (2.8 MILES) 2009-2015 TIP (June 2008) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $4.4 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 I-40/85 ALAMANCE I-4714 NC 49 (MILEPOST 145) TO NC 54 (MILEPOST 5898 869 IMPM CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 1676 148). MILL AND RESURFACE. (2.8 MILES) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $4.4 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 2011-2020 Draft TIP (August 2010) I-40/I-85 ALAMANCE I-4918 NC 54 (MILE POST 148) IN ALAMANCE COUNTY 9361 9361 IMPM CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 TO WEST OF SR 1114 (BUCKHORN ROAD) IN ORANGE ORANGE COUNTY. MILL AND RESURFACE. (8.3 MILES) 2009-2015 TIP (June 2008) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $12.0 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 I-40/I-85 ALAMANCE I-4918 NC 54 (MILEPOST 148) IN ALAMANCE COUNTY 15906 2120 IMPM CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 4595 TO WEST OF SR 1114 (BUCKHORN ROAD) IN ORANGE ORANGE COUNTY. -

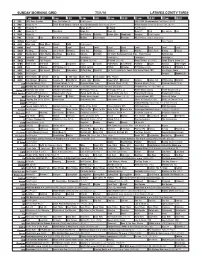

Sunday Morning Grid 7/31/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/31/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program 2016 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å 2016 Ricoh Women’s British Open Championship Final Round. (N) Å Action Sports From Long Beach, Calif. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Pregame MLS Soccer: Timbers at Sporting 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Mom Mkver Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Eat Dirt-Axe 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program El Chavo (N) (TVG) Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (N) (TV14) Como Dice el Dicho (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Choques El Príncipe (TV14) Fútbol Central Fútbol Choques El Príncipe (TV14) Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl On the Psychiatrist’s Couch With Daniel Amen, MD San Diego: Above 52 KVEA Paid Program Enfoque Haywire (R) 56 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up J. -

WWE Battleground/Seth Rollins Predictions

Is The Future Of Wrestling Now? WWE Battleground/Seth Rollins Predictions Author : When Seth Rollins first stabbed his brothers in “The Shield” in the back, he joined “The Authority” and proclaimed himself the Future of the WWE. Why shouldn’t he … He was on top of the world. He had the protection of Triple H and the rest of the stable, he had the Money in the Bank contract and then, he had the World Title. With the Championship came a bit of hubris for Rollins. That Hubris has caused him to alienate all who have been around to help him and protect him. He had made up with them before his big title match with Brock Lesnar at Battleground, giving J&J Security Apple Watches and a brand new Cadillac, and he gave Kane an Apple Watch and a trip to Hawaii. It seemed to work as they ALL had Rollin’s back when Lesnar showed up on RAW. But all that did was piss off the Beast. Lesnar then went and tore apart the Caddy and had it junked. While he was doing that he broke Jamie Noble’s arm and suplexed Joey Mercury through the windshield, putting them both out of action. Then last week on RAW, Lesnar dropped the steel steps on Kane’s ankle. That pissed Rollins off so much; he then yelled at Kane and jumped on his ankle. So you can cross off the Devil’s favorite Demon off of Rollins protection list heading into Battleground. So what IS going to happen to the “Future” of the WWE? Here is one mans informed opinion.