The Information Battleground: Terrorist Violence and the Role of the Media 291

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unintended Consequences of the American Presidential Selection System

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLP\15-1\HLP104.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-JUL-21 12:54 The Best Laid Plans: Unintended Consequences of the American Presidential Selection System Samuel S.-H. Wang and Jacob S. Canter* The mechanism for selecting the President of the United States, the Electoral College, causes outcomes that weaken American democracy and that the delegates at the Constitu- tional Convention never intended. The core selection process described in Article II, Section 1 was hastily drawn in the final days of the Convention based on compromises made originally to benefit slave-owning states and states with smaller populations. The system was also drafted to have electors deliberate and then choose the President in an age when travel and news took weeks or longer to cross the new country. In the four decades after ratification, the Electoral College was modified further to reach its current form, which includes most states using a winner-take-all method to allocate electors. The original needs this system was designed to address have now disappeared. But the persistence of these Electoral College mechanisms still causes severe unanticipated problems, including (1) con- tradictions between the electoral vote winner and national popular vote winner, (2) a “battleground state” phenomenon where all but a handful of states are safe for one political party or the other, (3) representational and policy benefits that citizens in only some states receive, (4) a decrease in the political power of non-battleground demographic groups, and (5) vulnerability of elections to interference. These outcomes will not go away without intervention. -

POLL RESULTS: Congressional Bipartisanship Nationwide and in Battleground States

POLL RESULTS: Congressional Bipartisanship Nationwide and in Battleground States 1 Voters think Congress is dysfunctional and reject the suggestion that it is effective. Please indicate whether you think this word or phrase describes the United States Congress, or not. Nationwide Battleground Nationwide Independents Battleground Independents Dysfunctional 60 60 61 64 Broken 56 58 58 60 Ineffective 54 54 55 56 Gridlocked 50 48 52 50 Partisan 42 37 40 33 0 Bipartisan 7 8 7 8 Has America's best 3 2 3 interests at heart 3 Functioning 2 2 2 3 Effective 2 2 2 3 2 Political frustrations center around politicians’ inability to collaborate in a productive way. Which of these problems frustrates you the most? Nationwide Battleground Nationwide Independents Battleground Independents Politicians can’t work together to get things done anymore. 41 37 41 39 Career politicians have been in office too long and don’t 29 30 30 30 understand the needs of regular people. Politicians are politicizing issues that really shouldn’t be 14 13 12 14 politicized. Out political system is broken and doesn’t work for me. 12 15 12 12 3 Candidates who brand themselves as bipartisan will have a better chance of winning in upcoming elections. For which candidate for Congress would you be more likely to vote? A candidate who is willing to compromise to A candidate who will stay true to his/her get things done principles and not make any concessions NationwideNationwide 72 28 Nationwide Nationwide Independents Independents 74 26 BattlegroundBattleground 70 30 Battleground Battleground IndependentsIndependents 73 27 A candidate who will vote for bipartisan A candidate who will resist bipartisan legislation legislation and stick with his/her party NationwideNationwide 83 17 Nationwide IndependentsNationwide Independents 86 14 BattlegroundBattleground 82 18 Battleground BattlegroundIndependents Independents 88 12 4 Across the country, voters agree that they want members of Congress to work together. -

The Popular Culture Studies Journal

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor Kevin Calcamp Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Wrestling” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of https://openclipart.org EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH FALON DEIMLER Minnesota State University, Moorhead University of Wisconsin-Madison JESSICA AUSTIN HANNAH DODD Anglia Ruskin University The Ohio State University AARON BARLOW ASHLEY M. DONNELLY New York City College of Technology (CUNY) Ball State University Faculty Editor, Academe, the magazine of the AAUP JOSEF BENSON LEIGH H. EDWARDS University of Wisconsin Parkside Florida State University PAUL BOOTH VICTOR EVANS DePaul University Seattle University GARY BURNS JUSTIN GARCIA Northern Illinois University Millersville University KELLI S. BURNS ALEXANDRA GARNER University of South Florida Bowling Green State University ANNE M. CANAVAN MATTHEW HALE Salt Lake Community College Indiana University, Bloomington ERIN MAE CLARK NICOLE HAMMOND Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota University of California, Santa Cruz BRIAN COGAN ART HERBIG Molloy College Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne JARED JOHNSON ANDREW F. HERRMANN Thiel College East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO MATTHEW NICOSIA Maryville University of St. -

Donald Trump 41% 55% 4%

August 13-17, 2017 / N=1,000 Registered voters / ±3.1% M.O.E. THE GEORGE WASHINGTON BATTLEGROUND POLL A national survey of 1,000 Registered Voters August 13-17, 2017 / N=1,000 Registered voters / ±3.1% M.O.E. Do you feel things in the country are going in the right direction, or do you feel things have gotten off on the wrong track? 70% 69% 66% 66% 64% 65% 63% 64% 58% 30% 28% 26% 26% 27% 27% 28% 21% 21% 14% 11% 10% 8% 9% 8% 7% 6% 9% 3/20/2014 8/28/2014 12/11/2014 5/7/2015 4/20/2016 9/1/2016 10/13/2016 12/1/2016 8/17/2017 Right direction Unsure Wrong track Q1 August 13-17, 2017 / N=1,000 Registered voters/Split sample A/B/ ±3.1% M.O.E. Do you feel things in the country are going in the right direction, or do you feel things have gotten off on the wrong track? 72% 75% 73% 70% 69% 67% 67% 65%66%66% 63%64% 63% 64% 62% 62% 61% 60% 59% 59% 59% 64% 58% 56% 57%56%57% 55% 55% 54% 54% 59% 54% 52% 51% 40% 41% 34% 40% 39% 38% 38% 39% 37% 37% 28% 36% 34% 28% 32% 32% 33%32% 26% 31% 31% 30% 29% 28% 28% 27% 27% 21%21% 26% 24% 6/1/04 8/1/0410/1/043/1/05 10/1/052/1/06 9/1/06 7/1/0912/1/094/8/10 8/1/109/21/1010/21/105/12/119/1/11 11/11/112/12/125/1/128/12/129/20/129/27/1210/18/1211/5/1212/6/1210/31/131/16/143/14/148/28/1412/11/145/7/154/20/169/1/16 10/13/1612/1/168/17/17 Right Direction Wrong Track Unsure Q1 August 13-17, 2017 / N=1,000 Registered voters / ±3.1% M.O.E. -

The Atlantic Return and the Payback of Evangelization

Vol. 3, no. 2 (2013), 207-221 | URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-114482 The Atlantic Return and the Payback of Evangelization VALENTINA NAPOLITANO* Abstract This article explores Catholic, transnational Latin American migration to Rome as a gendered and ethnicized Atlantic Return, which is figured as a source of ‘new blood’ that fortifies the Catholic Church but which also profoundly unset- tles it. I analyze this Atlantic Return as an angle on the affective force of his- tory in critical relation to two main sources: Diego Von Vacano’s reading of the work of Bartolomeo de las Casas, a 16th-century Spanish Dominican friar; and to Nelson Maldonado-Torres’ notion of the ‘coloniality of being’ which he suggests has operated in Atlantic relations as enduring and present forms of racial de-humanization. In his view this latter can be counterbalanced by embracing an economy of the gift understood as gendered. However, I argue that in the light of a contemporary payback of evangelization related to the original ‘gift of faith’ to the Americas, this economy of the gift is less liberatory than Maldonado-Torres imagines, and instead part of a polyfaceted reproduc- tion of a postsecular neoliberal affective, and gendered labour regime. Keywords Transnational migration; Catholicism; economy of the gift; de Certeau; Atlantic Return; Latin America; Rome. Author affiliation Valentina Napolitano is an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthro- pology and the Director of the Latin American Studies Program, University of *Correspondence: Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, 19 Russell St., Toronto, M5S 2S2, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (3.0) Religion and Gender | ISSN: 1878-5417 | www.religionandgender.org | Igitur publishing Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 10:21:12AM via free access Napolitano: The Atlantic Return and the Payback of Evangelization Toronto. -

Environmental Standards, Thresholds, and the Next Battleground of Climate Change Regulations

Article Environmental Standards, Thresholds, and the Next Battleground of Climate Change Regulations Kimberly M. Castle† and Richard L. Revesz†† Introduction .......................................................................... 1350 I. Traditional Risk Assessment Models ............................. 1363 A. Carcinogens ............................................................... 1363 B. Noncarcinogens Other than Criteria Pollutants ..... 1371 II. Treatment of Criteria Pollutants ................................... 1377 A. Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 ......................... 1378 B. Shift in the EPA’s Approach: A Case Study of Lead ....................................................................... 1383 C. Rejecting Thresholds and Calculating Benefits Below the NAAQS .................................................... 1391 III. Calculating Health Benefits from Particulate Matter Reductions Below the NAAQS ....................................... 1397 A. Scientific Basis .......................................................... 1400 B. Regulatory Treatment .............................................. 1409 C. Addressing Uncertainty ........................................... 1413 D. Adjusting Baselines .................................................. 1417 IV. Considering Co-Benefits ................................................. 1421 A. Co-Benefits and Indirect Costs ................................ 1424 B. The EPA’s Practice ................................................... 1427 † Research Scholar, Institute -

Neutral Ground Or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston American Studies Faculty Publication Series American Studies 2018 Neutral Ground or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter Lynnell L. Thomas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/amst_faculty_pubs Part of the African American Studies Commons, Africana Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, and the Tourism Commons Neutral Ground or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter Lynnell L. Thomas The National Slave Ship Museum will be the next great attraction for visitors and locals to experience. It will reconnect Americans to their complicated and rich history and provide a neutral ground for all of us to examine the costs of our country’s development. —LaToya Cantrell, New Orleans councilmember, 20151 In 2017, the city of New Orleans removed four monuments that paid homage to the city’s Confederate past. The removal came after contentious public de- bate and decades of intermittent grassroots protests. Despite the public process, details about the removal were closely guarded in the wake of death threats, vandalism, lawsuits, and organized resistance by monument supporters. Work- Lynnell L. Thomas is Associate Professor of American Studies at University of Massachusetts Boston. Research for this article was made possible by a grant from the College of the Liberal Arts Dean’s Research Fund, University of Massachusetts Boston. I would also like to thank Leon Waters for agreeing to be interviewed for this article. 1. In 2017, Cantrell was elected mayor of New Orleans; see “LaToya Cantrell Elected New Or- leans’ First Female Mayor,” http://www.nola.com/elections/index.ssf/2017/11/latoya_cantrell _elected_new_or.html. -

Deindustrialization, White Voter Backlash, and US Presidential Voting

American Political Science Review (2021) 115, 2, 550–567 doi:10.1017/S0003055421000022 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the American Political Science Association Gone For Good: Deindustrialization, White Voter Backlash, and US Presidential Voting LEONARDO BACCINI McGill University STEPHEN WEYMOUTH Georgetown University lobalization and automation have contributed to deindustrialization and the loss of millions of manufacturing jobs, yielding important electoral implications across advanced democracies. G Coupling insights from economic voting and social identity theory, we consider how different https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000022 groups in society may construe manufacturing job losses in contrasting ways. We argue that deindustrial- . ization threatens dominant group status, leading some white voters in affected localities to favor candidates they believe will address economic distress and defend racial hierarchy. Examining three US presidential elections, we find white voters were more likely to vote for Republican challengers where manufacturing layoffs were high, whereas Black voters in hard-hit localities were more likely to vote for Democrats. In survey data, white respondents, in contrast to people of color, associated local manufacturing job losses with obstacles to individual upward mobility and with broader American economic decline. Group-based identities help explain divergent political reactions to common economic shocks. INTRODUCTION about their perceived status as the dominant economic https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms and social group (Cramer 2016; Hochschild 2018; Ingle- n Janesville: An American Story, Amy Goldstein hart and Norris 2017; Jardina 2019; Mutz 2018; Sides, I describes how the closure of a century-old General Tesler, and Vavreck 2018), we contend that deindus- Motors (GM) plant reverberated throughout the trialization represents a politically salient status threat community of Janesville, Wisconsin (Goldstein 2017). -

Funding Report

PROGRAMS I STATE CASH FLOW * R FED CASH FLOW * COMPARE REPORT U INTRASTATE * LOOPS * UNFUNDED * FEASIBILITY * DIVISION 7 TYPE OF WORK / ESTIMATED COST IN THOUSANDS / PROJECT BREAK TOTAL PRIOR STATE TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM PROJ YEARS 5 YEAR WORK PROGRAM DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRAM "UNFUNDED" LOCATION / DESCRIPTION COST COST FUNDING ID (LENGTH) ROUTE/CITY COUNTY NUMBER (THOU) (THOU) SOURCE FY 2009 FY 2010 FY 2011 FY 2012 FY 2013 FY 2014 FY 2015 FY 2016 FY 2017 FY 2018 FY 2019 FY 2020 FUTURE YEARS 2011-2020 Draft TIP (August 2010) I-40/85 ALAMANCE I-4714 NC 49 (MILE POST 145) TO NC 54 (MILE 7551 7551 IMPM CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 POST 148). MILL AND RESURFACE. (2.8 MILES) 2009-2015 TIP (June 2008) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $4.4 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 I-40/85 ALAMANCE I-4714 NC 49 (MILEPOST 145) TO NC 54 (MILEPOST 5898 869 IMPM CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 1676 148). MILL AND RESURFACE. (2.8 MILES) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $4.4 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 2011-2020 Draft TIP (August 2010) I-40/I-85 ALAMANCE I-4918 NC 54 (MILE POST 148) IN ALAMANCE COUNTY 9361 9361 IMPM CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 TO WEST OF SR 1114 (BUCKHORN ROAD) IN ORANGE ORANGE COUNTY. MILL AND RESURFACE. (8.3 MILES) 2009-2015 TIP (June 2008) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $12.0 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 I-40/I-85 ALAMANCE I-4918 NC 54 (MILEPOST 148) IN ALAMANCE COUNTY 15906 2120 IMPM CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 4595 TO WEST OF SR 1114 (BUCKHORN ROAD) IN ORANGE ORANGE COUNTY. -

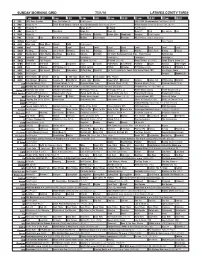

Sunday Morning Grid 7/31/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/31/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program 2016 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å 2016 Ricoh Women’s British Open Championship Final Round. (N) Å Action Sports From Long Beach, Calif. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Pregame MLS Soccer: Timbers at Sporting 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Mom Mkver Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Eat Dirt-Axe 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program El Chavo (N) (TVG) Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (N) (TV14) Como Dice el Dicho (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Choques El Príncipe (TV14) Fútbol Central Fútbol Choques El Príncipe (TV14) Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl On the Psychiatrist’s Couch With Daniel Amen, MD San Diego: Above 52 KVEA Paid Program Enfoque Haywire (R) 56 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up J. -

A New Battleground Nadine Sayegh, Mhadeen Barik, Bondokji Neven

FROM BLADES TO BRAINS: A New Battleground Nadine Sayegh, Mhadeen Barik, Bondokji Neven To cite this version: Nadine Sayegh, Mhadeen Barik, Bondokji Neven. FROM BLADES TO BRAINS: A New Battle- ground. [Research Report] The WANA Institute; The Embassy of the Netherlands in Jordan. 2017. hal-02149254 HAL Id: hal-02149254 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02149254 Submitted on 6 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. FROM BLADES TO BRAINS: A New Battleground West Asia-North Africa Institute, December 2017 All content of this publication was produced by Dr Neven Bondokji, Barik Mhadeen, and Nadine Sayegh. This publication is generously supported with funds from the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This publication reflects the views of the authors only, and not necessarily that of the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE The information in this publication may not be reproduced, in part or in whole and by any means, without charge or further permission from the WANA Institute. For permission to reproduce the information in this publication, please contact the WANA Institute Communications Department at [email protected]. Published by the WANA Institute, Royal Scientific Society in Amman, Jordan Authors: Nadine Sayegh, Barik Mhadeen, Dr Neven Bondokji Editor: Alethea Osborne Design: Lien Santermans Cover image: Geralt (CC0) Printed in Amman, Jordan © 2017 WANA Institute. -

WWE Battleground/Seth Rollins Predictions

Is The Future Of Wrestling Now? WWE Battleground/Seth Rollins Predictions Author : When Seth Rollins first stabbed his brothers in “The Shield” in the back, he joined “The Authority” and proclaimed himself the Future of the WWE. Why shouldn’t he … He was on top of the world. He had the protection of Triple H and the rest of the stable, he had the Money in the Bank contract and then, he had the World Title. With the Championship came a bit of hubris for Rollins. That Hubris has caused him to alienate all who have been around to help him and protect him. He had made up with them before his big title match with Brock Lesnar at Battleground, giving J&J Security Apple Watches and a brand new Cadillac, and he gave Kane an Apple Watch and a trip to Hawaii. It seemed to work as they ALL had Rollin’s back when Lesnar showed up on RAW. But all that did was piss off the Beast. Lesnar then went and tore apart the Caddy and had it junked. While he was doing that he broke Jamie Noble’s arm and suplexed Joey Mercury through the windshield, putting them both out of action. Then last week on RAW, Lesnar dropped the steel steps on Kane’s ankle. That pissed Rollins off so much; he then yelled at Kane and jumped on his ankle. So you can cross off the Devil’s favorite Demon off of Rollins protection list heading into Battleground. So what IS going to happen to the “Future” of the WWE? Here is one mans informed opinion.