WWE: Redefining Orking-Classw Womanhood Through Commodified Eminismf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Power Seeking and Backlash Against Female Politicians

Article Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin The Price of Power: Power Seeking and 36(7) 923 –936 © 2010 by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc Backlash Against Female Politicians Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0146167210371949 http://pspb.sagepub.com Tyler G. Okimoto1 and Victoria L. Brescoll1 Abstract Two experimental studies examined the effect of power-seeking intentions on backlash toward women in political office. It was hypothesized that a female politician’s career progress may be hindered by the belief that she seeks power, as this desire may violate prescribed communal expectations for women and thereby elicit interpersonal penalties. Results suggested that voting preferences for female candidates were negatively influenced by her power-seeking intentions (actual or perceived) but that preferences for male candidates were unaffected by power-seeking intentions. These differential reactions were partly explained by the perceived lack of communality implied by women’s power-seeking intentions, resulting in lower perceived competence and feelings of moral outrage. The presence of moral-emotional reactions suggests that backlash arises from the violation of communal prescriptions rather than normative deviations more generally. These findings illuminate one potential source of gender bias in politics. Keywords gender stereotypes, backlash, power, politics, intention, moral outrage Received June 5, 2009; revision accepted December 2, 2009 Many voters see Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton as coldly politicians and that these penalties may be reflected in voting ambitious, a perception that could ultimately doom her presi- preferences. dential campaign. Peter Nicholas, Los Angeles Times, 2007 Power-Relevant Stereotypes Power seeking may be incongruent with traditional female In 1916, Jeannette Rankin was elected to the Montana seat in gender stereotypes but not male gender stereotypes for a the U.S. -

The Rise of Controversial Content in Film

The Climb of Controversial Film Content by Ashley Haygood Submitted to the Department of Communication Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Communication at Liberty University May 2007 Film Content ii Abstract This study looks at the change in controversial content in films during the 20th century. Original films made prior to 1968 and their remakes produced after were compared in the content areas of profanity, nudity, sexual content, alcohol and drug use, and violence. The advent of television, post-war effects and a proposed “Hollywood elite” are discussed as possible causes for the increase in controversial content. Commentary from industry professionals on the change in content is presented, along with an overview of American culture and the history of the film industry. Key words: film content, controversial content, film history, Hollywood, film industry, film remakes i. Film Content iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for their unwavering support during the last three years. Without their help and encouragement, I would not have made it through this program. I would also like to thank the professors of the Communications Department from whom I have learned skills and information that I will take with me into a life-long career in communications. Lastly, I would like to thank my wonderful Thesis committee, especially Dr. Kelly who has shown me great patience during this process. I have only grown as a scholar from this experience. ii. Film Content iv Table of Contents ii. Abstract iii. Acknowledgements I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………1 II. Review of the Literature……………………………………………………….8 a. -

The Universe of the Wwe!

At first glance, this world seems quite similar to yours. Tech's at a pretty normal level (for humanity, anyway) and you're beginning to question whether or not you ended up back home. Next thing you know, you're getting a tap on your shoulder. Holy shit, that's Vince McMahon, with a contract for you to sign! Which means that this must be… THE UNIVERSE OF THE WWE! That's right- You're going into a realm where every bit of fluff, every backstory, every cheesy legend has been brought to an equally cheesy life. No scripts here- everything is real. The grudges, the personalities- all of it is 100% unfaked. Even the world outside of wrestling is very similar to what you'd find in the ring, similar to what you'd expect to find in an '80s action movie. You're going to get in the ring with some of wrestling's greatest legends- But will you be getting in the ring with Hulk Hogan or the rock? Or maybe you'll be standing toe to toe with Roman Reigns? Or maybe you mean to go back to the early 60s, back when it was still the National Wrestling Alliance, and help Vince McMahon sr. create the WWE? Let's find out. Roll 1d4 to find out what year you start in, or pay 100 CP to choose freely. 1: 1960: The beginning of the WWE. In 3 years, Buddy Rogers will lose the title of the National Wrestling Alliance in a bad match, and in protest, Vince McMahon Sr. -

Frontlash/Backlash: the Crisis of Solidarity and the Threat to Civil Institutions

Ó American Sociological Association 2018 DOI: 10.1177/0094306118815497 http://cs.sagepub.com FEATURED ESSAY Frontlash/Backlash: The Crisis of Solidarity and the Threat to Civil Institutions JEFFREY C. ALEXANDER Yale University [email protected] It is fear and loathing time for the left, sociol- The first thing to recognize is that ogists prominently among them. Loathing Trumpism and the alt-right are nothing for President Trump, champion of the alt- new, not here, not anywhere where right forces that, marginalized for decades, civil spheres have been simultaneously are bringing bigotry, patriarchy, nativism, and enabled and constrained. The depredations nationalism back into a visible place in the of Trumpism are not unique, first-time-in- American civil sphere. Fear that these threaten- American-history things. What they con- ing forces may succeed, that democracy will be stitute, instead, are backlash movements destroyed, and that the egalitarian achieve- (Alexander 2013). ments of the last five decades will be lost. Fem- Sociologists have had a bad habit of think- inism, anti-racism, multiculturalism, sexual cit- ing of social change as linear, a secular trend izenship, ecology, and internationalism—all that is broadly progressive, rooted in the these precarious achievements have come enlightening habits of modernity, education, under vicious, persistent attack. economic expansion, and the shared social Fear and loathing can be productive when interests of humankind (Marshall 1965; they are unleashed inside the culture and Parsons 1967; Habermas [1984, 1987] 1981; social structures of a civil sphere that remains Giddens 1990). From such a perspective, con- vigorous and a vital center (Schlesinger 1949; servative movements appear as deviations, Alexander 2016; Kivisto 2019) that, even if reflecting anomie and isolation (Putnam fragile, continues to hold. -

PRESCRIPTION DRUG COUPON STUDY Report to the Massachusetts Legislature JULY 2020

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS HEALTH POLICY COMMISSION PRESCRIPTION DRUG COUPON STUDY Report to the Massachusetts Legislature JULY 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In this report, required by Chapter 363 of the 2018 Session Prescription drug coupons are currently allowed in all 50 Laws, the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission (HPC) states for commercially-insured patients. Federal health examines the use and impact of prescription drug coupons insurance programs, such as Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare in Massachusetts. This report focuses on coupons issued by and Veteran’s Administration, prohibit the use of coupons pharmaceutical manufacturers that reduce a commercial based on federal anti-kickback statutes. Massachusetts patient’s cost-sharing. Prescription drug coupons are offered became the last state to authorize commercial coupon use almost exclusively on branded drugs, which comprise only in 2012 but continues to prohibit manufacturers from 10% of all prescriptions dispensed in the U.S., but account offering coupons and discounts on any prescription drug for 79% of total drug spending. Despite the immediate ben- that has an “AB rated” generic equivalent as determined efit of drug coupons to patients, policymakers and experts by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The 2012 debate whether and how coupons should be allowed in the law authorizing coupons in Massachusetts also contained commercial market given the potential relationship between a sunset provision, under which the law would have been coupon usage and increased spending on branded drugs repealed on July 1, 2015. However, this date of repeal versus lower cost alternatives. was postponed several times and ultimately extended to January 1, 2021. Massachusetts has long sought to con- Coupons reduce or eliminate the patient’s cost-sharing sider the impact of drug coupons on the Commonwealth’s responsibility required by the patient’s insurance plan, while landmark cost containment goals, as well as the benefits for the plan’s costs for the drug remain unchanged. -

What Men Have to Do with It | Executive Summary 4

what menhave to do with it Public Policies to Promote Gender Equality coordinated by the International Center for Research on Women and Instituto Promundo ABOUT THE MEN AND GENDER EQUALITY POLICY PROJECT The Men and Gender Equality Policy Project (MGEPP), coordinated by Instituto Promundo and the International Center for Research on Women, is a multi-year effort to build the evidence base on how to change public institutions and policies to better foster gender equality and to raise awareness among policymakers and program planners of the need to involve men in health, development and gender equality issues. Project activities include: (1) a multi-country policy research and analysis presented in this publication; (2) the International Men and Gender Equality Survey, or IMAGES, a quantitative household survey carried out with men and women in six countries in 2009, with additional countries implementing the survey in 2010 and thereafter; (3) the “Men who Care” study consisting of in-depth qualitative life history interviews with men in five countries, and (4) advocacy efforts and dissemination of the findings from these components via various formats, including a video produced by documentary filmmaker Rahul Roy. Participating countries in the project, as of 2009, include Brazil, Chile, Croatia, India, Mexico, South Africa, and Tanzania. The project’s multiple research components aim to provide policymakers with practical strategies for engaging men in relevant policy areas, particularly in the areas of sexual and reproductive health, gender-based violence, fatherhood and maternal and child health, and men’s own health needs. PHOTO CREDITS cover (left to right): © Ping-hang Chen, Influential Men; © Richard Lewisohn, Influential Men; (top right) © Marie Swartz, Influential Men; Shana Pereira/ICRW back cover: © Sophie Joy Mosko, Influential Men what menhave to do with it Public Policies to Promote Gender Equality AUTHORS: CONTENTS: Gary Barker Margaret E. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

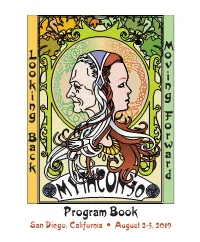

Mythcon 50 Program Book

M L o o v o i k n i g n g F o r B w a a c r k d Program Book San Diego, California • August 2-5, 2019 Mythcon 50: Moving Forward, Looking Back Guests of Honor Verlyn Flieger, Tolkien Scholar Tim Powers, Fantasy Author Conference Theme To give its far-flung membership a chance to meet, and to present papers orally with audience response, The Mythopoeic Society has been holding conferences since its early days. These began with a one-day Narnia Conference in 1969, and the first annual Mythopoeic Conference was held at the Claremont Colleges (near Los Angeles) in September, 1970. This year’s conference is the third in a series of golden anniversaries for the Society, celebrating our 50th Mythcon. Mythcon 50 Committee Lynn Maudlin – Chair Janet Brennan Croft – Papers Coordinator David Bratman – Programming Sue Dawe – Art Show Lisa Deutsch Harrigan – Treasurer Eleanor Farrell – Publications J’nae Spano – Dealers’ Room Marion VanLoo – Registration & Masquerade Josiah Riojas – Parking Runner & assistant to the Chair Venue Mythcon 50 will be at San Diego State University, with programming in the LEED Double Platinum Certified Conrad Prebys Aztec Student Union, and onsite housing in the South Campus Plaza, South Tower. Mythcon logo by Sue Dawe © 2019 Thanks to Carl Hostetter for the photo of Verlyn Flieger, and to bg Callahan, Paula DiSante, Sylvia Hunnewell, Lynn Maudlin, and many other members of the Mythopoeic Society for photos from past conferences. Printed by Windward Graphics, Phoenix, AZ 3 Verlyn Flieger Scholar Guest of Honor by David Bratman Verlyn Flieger and I became seriously acquainted when we sat across from each other at the ban- quet of the Tolkien Centenary Conference in 1992. -

Children, Technology and Play

Research report Children, technology and play Marsh, J., Murris, K., Ng’ambi, D., Parry, R., Scott, F., Thomsen, B.S., Bishop, J., Bannister, C., Dixon, K., Giorza, T., Peers, J., Titus, S., Da Silva, H., Doyle, G., Driscoll, A., Hall, L., Hetherington, A., Krönke, M., Margary, T., Morris, A., Nutbrown, B., Rashid, S., Santos, J., Scholey, E., Souza, L., and Woodgate, A. (2020) Children, Technology and Play. Billund, Denmark: The LEGO Foundation. June 2020 ISBN: 978-87-999589-7-9 Table of contents Table of contents Section 1: Background to the study • 4 1.1 Introduction • 4 1.2 Aims, objectives and research questions • 4 1.3 Methodology • 5 Section 2: South African and UK survey findings • 8 2.1 Children, technology and play: South African survey data analysis • 8 2.2 Children, technology and play: UK survey data analysis • 35 2.3 Summary • 54 Section 3: Pen portraits of case study families and children • 56 3.1 South African case study family profiles • 57 3.2 UK case study family profiles • 72 3.3 Summary • 85 Section 4: Children’s digital play ecologies • 88 4.1 Digital play ecologies • 88 4.2 Relationality and children’s digital ecologies • 100 4.3 Children’s reflections on digital play • 104 4.4 Summary • 115 Section 5: Digital play and learning • 116 5.1 Subject knowledge and understanding • 116 5.2 Digital skills • 119 5.3 Holistic skills • 120 5.4 Digital play in the classroom • 139 5.5 Summary • 142 2 Table of contents Section 6: The five characteristics of learning through play • 144 6.1 Joy • 144 6.2 Actively engaging • 148 -

A Cultural Analysis of a Physicist ''Trio'' Supporting the Backlash Against

ARTICLE IN PRESS Global Environmental Change 18 (2008) 204–219 www.elsevier.com/locate/gloenvcha Experiences of modernity in the greenhouse: A cultural analysis of a physicist ‘‘trio’’ supporting the backlash against global warming Myanna Lahsenà Center for Science and Technology Policy Research, University of Colorado and Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Epaciais (INPE), Av. dos Astronautas, 1758, Sa˜o Jose´ dos Campos, SP 12227-010 Brazil Received 18 March 2007; received in revised form 5 October 2007; accepted 29 October 2007 Abstract This paper identifies cultural and historical dimensions that structure US climate science politics. It explores why a key subset of scientists—the physicist founders and leaders of the influential George C. Marshall Institute—chose to lend their scientific authority to this movement which continues to powerfully shape US climate policy. The paper suggests that these physicists joined the environmental backlash to stem changing tides in science and society, and to defend their preferred understandings of science, modernity, and of themselves as a physicist elite—understandings challenged by on-going transformations encapsulated by the widespread concern about human-induced climate change. r 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Anti-environmental movement; Human dimensions research; Climate change; Controversy; United States; George C. Marshall Institute 1. Introduction change itself, what he termed a ‘‘strong theory of culture.’’ Arguing that the essential role of science in our present age Human Dimensions Research in the area of global only can be fully understood through examination of environmental change tends to integrate a limited con- individuals’ relationships with each other and with ‘‘mean- ceptualization of culture. -

The Gay Marriage Backlash and Its Spillover Effects: Lessons from a (Slightly) Blue State

Tulsa Law Review Volume 40 Issue 3 The Legislative Backlash to Advances in Rights for Same-Sex Couples Spring 2005 The Gay Marriage Backlash and Its Spillover Effects: Lessons from a (Slightly) Blue State John G. Culhane Stacey L. Sobel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation John G. Culhane, & Stacey L. Sobel, The Gay Marriage Backlash and Its Spillover Effects: Lessons from a (Slightly) Blue State, 40 Tulsa L. Rev. 443 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol40/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Culhane and Sobel: The Gay Marriage Backlash and Its Spillover Effects: Lessons from THE GAY MARRIAGE BACKLASH AND ITS SPILLOVER EFFECTS: LESSONS FROM A (SLIGHTLY) "BLUE STATE" John G. Culhane* and Stacey L. Sobel** I. INTRODUCTION Backlash, indeed! The stories streaming in from across the country can scarcely be believed. In Alabama, a legislator introduced a bill that would have banished any mention of homosexuality from all public libraries-even at the university level.' In Virginia, the legislature's enthusiasm for joining the chorus of states that have amended their constitutions to ban gay marriage was eclipsed by a legislator's suggestion that the state's license plates be pressed into service as political slogans, and made to read: "Traditional Marriage. -

Article Racial Capitalism

VOLUME 126 JUNE 2013 NUMBER 8 © 2013 by The Harvard Law Review Association ARTICLE RACIAL CAPITALISM Nancy Leong CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2153 I. VALUING RACE ................................................................................................................... 2158 A. Whiteness as Property .................................................................................................... 2158 B. Diversity as Revaluation ................................................................................................ 2161 C. The Worth of Nonwhiteness .......................................................................................... 2169 II. A THEORY OF RACIAL CAPITALISM .............................................................................. 2172 A. Race as Social Capital .................................................................................................... 2175 B. Race as Marxian Capital ............................................................................................... 2183 C. Racial Capitalism ............................................................................................................ 2190 III. CRITIQUING RACIAL CAPITALISM ................................................................................. 2198 A. Commodification ............................................................................................................. 2199 B. Harm