Unintended Consequences of the American Presidential Selection System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Popular Culture Studies Journal

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor Kevin Calcamp Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Wrestling” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of https://openclipart.org EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH FALON DEIMLER Minnesota State University, Moorhead University of Wisconsin-Madison JESSICA AUSTIN HANNAH DODD Anglia Ruskin University The Ohio State University AARON BARLOW ASHLEY M. DONNELLY New York City College of Technology (CUNY) Ball State University Faculty Editor, Academe, the magazine of the AAUP JOSEF BENSON LEIGH H. EDWARDS University of Wisconsin Parkside Florida State University PAUL BOOTH VICTOR EVANS DePaul University Seattle University GARY BURNS JUSTIN GARCIA Northern Illinois University Millersville University KELLI S. BURNS ALEXANDRA GARNER University of South Florida Bowling Green State University ANNE M. CANAVAN MATTHEW HALE Salt Lake Community College Indiana University, Bloomington ERIN MAE CLARK NICOLE HAMMOND Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota University of California, Santa Cruz BRIAN COGAN ART HERBIG Molloy College Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne JARED JOHNSON ANDREW F. HERRMANN Thiel College East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO MATTHEW NICOSIA Maryville University of St. -

Battleground 2014 (XLIII)

Battleground 2014 (XLIII) FINAL STUDY #14107 THE TARRANCE GROUP and LAKE RESEARCH PARTNERS N = 1,000 Registered “likely” voters Margin of error + 3.1% Field Dates: January 12-16, 2014 Hello, I'm _______________ of The Tarrance Group, a national survey research firm. We're talking to people today about public leaders and issues facing us all. IF CELL CODE = “N”, ASK: May I please speak with the youngest (male/female) in the household who is registered to vote? IF CELL CODE = “Y”, ASK: CP-1. Do you currently live in (state from cell sample sheet)? Yes (CONTINUE TO CP-3) No (CONTINUE TO CP-2) _____________________________________________________________________________________________ IF “NO” IN CP-1, ASK: CP-2. In what state do you current reside? __________________________ (RECORD STATE NAME) _____________________________________________________________________________________________ IF CELL CODE = “Y”, ASK: CP-3. For your safety, are you driving right now? Yes (SCHEDULE CALL BACK) No _____________________________________________________________________________________________ A. Are you registered to vote in your state? IF "NO," ASK: Is there someone else at home who is registered to vote? (IF "YES," THEN ASK: MAY I SPEAK WITH HIM/HER?) Yes (CONTINUE) No (THANK AND TERMINATE) *=less than .5% 1 And… B. What is the likelihood of your voting in the elections for US Congress that will be held in November 2014-- are you extremely likely, very likely, somewhat likely, or not very likely at all to vote? Extremely Likely ..................................................... 60% (CONTINUE) Very Likely .............................................................. 27% Somewhat Likely ..................................................... 13% (THANK AND TERMINATE) Not Very Likely UNSURE (DNR) (UPELECT) C. Are you, or is anyone in your household, employed with an advertising agency, newspaper, television or radio station, or political campaign? Yes (THANK AND TERMINATE) No (CONTINUE) Now, thinking for a moment about things in the country-- 1. -

Spreading the Gospel of Climate Change: an Evangelical Battleground

NEW POLITICAL REFORM NEW MODELS OF AMERICA PROGRAM POLICY CHANGE LYDIA BEAN AND STEVE TELES SPREADING THE GOSPEL OF CLIMATE CHANGE: AN EVANGELICAL BATTLEGROUND PART OF NEW AMERICA’S STRANGE BEDFELLOWS SERIES NOVEMBER 2015 #STRANGEBEDFELLOWS About the Authors About New Models of Policy Change Lydia Bean is author of The Politics New Models of Policy Change starts from the observation of Evangelical Identity (Princeton UP that the traditional model of foundation-funded, 2014). She is Executive Director of Faith think-tank driven policy change -- ideas emerge from in Texas, and Senior Consultant to the disinterested “experts” and partisan elites compromise PICO National Network. for the good of the nation -- is failing. Partisan polarization, technological empowerment of citizens, and heightened suspicions of institutions have all taken their toll. Steven Teles is an associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins But amid much stagnation, interesting policy change University and a fellow at New America. is still happening. The paths taken on issues from sentencing reform to changes in Pentagon spending to resistance to government surveillance share a common thread: they were all a result of transpartisan cooperation. About New America By transpartisan, we mean an approach to advocacy in which, rather than emerging from political elites at the New America is dedicated to the renewal of American center, new policy ideas emerge from unlikely corners of politics, prosperity, and purpose in the Digital Age. We the right or left and find allies on the other side, who may carry out our mission as a nonprofit civic enterprise: an come to the same idea from a very different worldview. -

The Atlantic Return and the Payback of Evangelization

Vol. 3, no. 2 (2013), 207-221 | URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-114482 The Atlantic Return and the Payback of Evangelization VALENTINA NAPOLITANO* Abstract This article explores Catholic, transnational Latin American migration to Rome as a gendered and ethnicized Atlantic Return, which is figured as a source of ‘new blood’ that fortifies the Catholic Church but which also profoundly unset- tles it. I analyze this Atlantic Return as an angle on the affective force of his- tory in critical relation to two main sources: Diego Von Vacano’s reading of the work of Bartolomeo de las Casas, a 16th-century Spanish Dominican friar; and to Nelson Maldonado-Torres’ notion of the ‘coloniality of being’ which he suggests has operated in Atlantic relations as enduring and present forms of racial de-humanization. In his view this latter can be counterbalanced by embracing an economy of the gift understood as gendered. However, I argue that in the light of a contemporary payback of evangelization related to the original ‘gift of faith’ to the Americas, this economy of the gift is less liberatory than Maldonado-Torres imagines, and instead part of a polyfaceted reproduc- tion of a postsecular neoliberal affective, and gendered labour regime. Keywords Transnational migration; Catholicism; economy of the gift; de Certeau; Atlantic Return; Latin America; Rome. Author affiliation Valentina Napolitano is an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthro- pology and the Director of the Latin American Studies Program, University of *Correspondence: Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, 19 Russell St., Toronto, M5S 2S2, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (3.0) Religion and Gender | ISSN: 1878-5417 | www.religionandgender.org | Igitur publishing Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 10:21:12AM via free access Napolitano: The Atlantic Return and the Payback of Evangelization Toronto. -

Environmental Standards, Thresholds, and the Next Battleground of Climate Change Regulations

Article Environmental Standards, Thresholds, and the Next Battleground of Climate Change Regulations Kimberly M. Castle† and Richard L. Revesz†† Introduction .......................................................................... 1350 I. Traditional Risk Assessment Models ............................. 1363 A. Carcinogens ............................................................... 1363 B. Noncarcinogens Other than Criteria Pollutants ..... 1371 II. Treatment of Criteria Pollutants ................................... 1377 A. Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 ......................... 1378 B. Shift in the EPA’s Approach: A Case Study of Lead ....................................................................... 1383 C. Rejecting Thresholds and Calculating Benefits Below the NAAQS .................................................... 1391 III. Calculating Health Benefits from Particulate Matter Reductions Below the NAAQS ....................................... 1397 A. Scientific Basis .......................................................... 1400 B. Regulatory Treatment .............................................. 1409 C. Addressing Uncertainty ........................................... 1413 D. Adjusting Baselines .................................................. 1417 IV. Considering Co-Benefits ................................................. 1421 A. Co-Benefits and Indirect Costs ................................ 1424 B. The EPA’s Practice ................................................... 1427 † Research Scholar, Institute -

2019-2020 Annual Report

Page 1 Program on Law and Government Annual Report: 2019-2020 Page 2 Welcome from the Faculty Director When this year started, we couldn’t begin to imagine the challenges and opportunities it would bring. We started with the typical rush of activities and expectation, but ended in the hectic and bewildering confinement of the COVID19 quarantine. Law school is ultimately about preparing for a career, and it’s hard to think about that when you’ve been asked to upend your life in the face of a global pandemic. We were reminded in the end that this time is a unique opportunity to step up from whatever role we’ve had into newer roles, for which no training can completely prepare us. Ultimately, that’s not dissimilar to lawyering at the intersection of law and government. We take on new challenges that seem daunting but rely on what we’ve learned -- and our ability to constantly learn new things -- to make a difference. Even as we move to programming more events online, we look forward to seeing you again face-to-face. As I said to students in January, in the face of so much that challenges and bewilders us, it’s good to remember that some things haven’t changed. Our faculty are still experts in their fields. Your friends and colleagues still have your back. And the work you’re doing still provides a solid foundation for the future. In his inaugural address on a cold January day in 1961, President John F. Kennedy famously encouraged Americans to “ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” This is our opportunity to write the narrative of how America meets a serious new challenge. -

Neutral Ground Or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston American Studies Faculty Publication Series American Studies 2018 Neutral Ground or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter Lynnell L. Thomas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/amst_faculty_pubs Part of the African American Studies Commons, Africana Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, and the Tourism Commons Neutral Ground or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter Lynnell L. Thomas The National Slave Ship Museum will be the next great attraction for visitors and locals to experience. It will reconnect Americans to their complicated and rich history and provide a neutral ground for all of us to examine the costs of our country’s development. —LaToya Cantrell, New Orleans councilmember, 20151 In 2017, the city of New Orleans removed four monuments that paid homage to the city’s Confederate past. The removal came after contentious public de- bate and decades of intermittent grassroots protests. Despite the public process, details about the removal were closely guarded in the wake of death threats, vandalism, lawsuits, and organized resistance by monument supporters. Work- Lynnell L. Thomas is Associate Professor of American Studies at University of Massachusetts Boston. Research for this article was made possible by a grant from the College of the Liberal Arts Dean’s Research Fund, University of Massachusetts Boston. I would also like to thank Leon Waters for agreeing to be interviewed for this article. 1. In 2017, Cantrell was elected mayor of New Orleans; see “LaToya Cantrell Elected New Or- leans’ First Female Mayor,” http://www.nola.com/elections/index.ssf/2017/11/latoya_cantrell _elected_new_or.html. -

Funding Report

PROGRAMS I STATE CASH FLOW * R FED CASH FLOW * COMPARE REPORT U INTRASTATE * LOOPS * UNFUNDED * FEASIBILITY * DIVISION 7 TYPE OF WORK / ESTIMATED COST IN THOUSANDS / PROJECT BREAK TOTAL PRIOR STATE TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM PROJ YEARS 5 YEAR WORK PROGRAM DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRAM "UNFUNDED" LOCATION / DESCRIPTION COST COST FUNDING ID (LENGTH) ROUTE/CITY COUNTY NUMBER (THOU) (THOU) SOURCE FY 2009 FY 2010 FY 2011 FY 2012 FY 2013 FY 2014 FY 2015 FY 2016 FY 2017 FY 2018 FY 2019 FY 2020 FUTURE YEARS 2011-2020 Draft TIP (August 2010) I-40/85 ALAMANCE I-4714 NC 49 (MILE POST 145) TO NC 54 (MILE 7551 7551 IMPM CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 POST 148). MILL AND RESURFACE. (2.8 MILES) 2009-2015 TIP (June 2008) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $4.4 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 I-40/85 ALAMANCE I-4714 NC 49 (MILEPOST 145) TO NC 54 (MILEPOST 5898 869 IMPM CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 1676 148). MILL AND RESURFACE. (2.8 MILES) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $4.4 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 2011-2020 Draft TIP (August 2010) I-40/I-85 ALAMANCE I-4918 NC 54 (MILE POST 148) IN ALAMANCE COUNTY 9361 9361 IMPM CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 TO WEST OF SR 1114 (BUCKHORN ROAD) IN ORANGE ORANGE COUNTY. MILL AND RESURFACE. (8.3 MILES) 2009-2015 TIP (June 2008) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $12.0 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 I-40/I-85 ALAMANCE I-4918 NC 54 (MILEPOST 148) IN ALAMANCE COUNTY 15906 2120 IMPM CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 4595 TO WEST OF SR 1114 (BUCKHORN ROAD) IN ORANGE ORANGE COUNTY. -

2014 Winners

Social and Digital Media Award Winners & Television Award Winners All Markets Large Market Television BEST WEBSITE FOCUSED ON JOURNALISM BEST SPOT NEWS 1st Place: WI Public Radio, WPR.ORG 1st Place: WITI TV, Police Officer Not Charged in Shooting 2nd Place: WUWM FM, WUWM.COM 2nd Place: WISN TV, Freeway Shutdown 3rd Place: WISC TV, Channel3000.com 3rd Place: WISN TV, Hamilton Decision BEST NON-NEWS WEBSITE (MUSIC & ENTERTAINMENT) BEST MORNING NEWSCAST 1st Place: WYMS FM, 88Nine Radio Milwaukee 1st Place: WISN TV, Miller Park Fire & Train Derailment Website 2nd Place: WTMJ TV, Verona Tornado Coverage 2nd Place: WOZZ FM, Rock 94.7 3rd Place: WITI TV, Fox6 Wakeup ‐ November 5 3rd Place: WKZG FM, www.myKZradio.com BEST EVENING NEWSCAST BEST NICHE WEBSITE 1st Place: WITI TV, FOX6 News at 5:00 ‐ December 22 1st Place: WUWM FM, WUWM "More than My Record" 2nd Place: WITI TV, FOX6 News at 9:00 ‐ June 26 2nd Place: WISC TV, Community Websites 3rd Place: WISN TV, Summer Storms 3rd Place: WYMS FM, 88Nine Radio Milwaukee BEST NEWS WRITING Voting Guide 1st Place: WITI TV, “Santa Bob” BEST SPECIAL WEB PROJECT 2nd Place: WISN TV, Potter Adoption 1st Place: WYMS FM, Field Report Interactive 3rd Place: WTMJ TV, The Ice Bucket Reality Timeline for Field Report Day BEST HARD NEWS/INVESTIGATIVE 2nd Place: WBAY TV, Flying with the Thunderbirds 1st Place: WTMJ TV, I‐Team: Cause for Alarm 3rd Place: WISC TV, Election Night Map 2nd Place: WTMJ TV, I‐Team: DPW on the Clock BEST USE OF USER-GENERATED CONTENT 3rd Place: WYTU TV, Suicidio: Decisión de vida o muerte -

OUR ORIGIN STORY:Explores How the Laws And

WHERE DID WE COME FROM? OUR ORIGIN STORY: Explores how the laws and values of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy were integral in the writing of the Constitution, yet Native Americans' cultural and religious traditions, and practices were outlawed until 1978. How people gather, express their cultural identities, and practice community continues to be an issue of contention in modern America. We examine how these issues manifest at the many levels of government and how we can approach these issues of religious and cultural freedoms with an equity lens with experts including Dr. Sally Roesch Wagner, Author of Sisters in Spirit: Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Influences on Early American Feminists, Prairie Rose Seminole, Policy Analyst, and Sabina Mohyuddin, Executive Director for the American Muslim Advisory Council. ● HOW THE IROQUOIS AND OTHER INDIAN NATIONS HELPED TO SHAPE THE VISION OF WOMEN AS EQUALS - Suffragettes2020.com A variety of links to different articles/essays that are focused on the iroquois women and their impact on modern day feminism. These impacts include voting rights for women, The Great Law of Peace, separation of church and state, etc. ● CONTROVERSIES OVER MOSQUES AND ISLAMIC CENTERS ACROSS THE U.S. - Pew Research A collection of information regarding different controversies over Mosques and Islamic Centers in the U.S. This piece includes an interactive map of the 53 proposed Mosque sites, as well as brief descriptions of each site. Descriptions include the original conflict over the sites and their status as of 2012. ● NEIGHBORS SUPPORT ISLAMIC CENTER OF GREATER CHATTANOOGA - Chattanooga Times Free Press This article from Chattanooga Times Free Press covers the grand opening of the Islamic Center of Greater Chattanooga, while also comparing this Islamic Center with that of the controversial Islamic Center of Murfreesboro. -

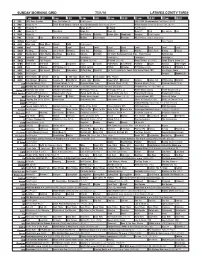

Sunday Morning Grid 7/31/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/31/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program 2016 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å 2016 Ricoh Women’s British Open Championship Final Round. (N) Å Action Sports From Long Beach, Calif. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Pregame MLS Soccer: Timbers at Sporting 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Mom Mkver Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Eat Dirt-Axe 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program El Chavo (N) (TVG) Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (N) (TV14) Como Dice el Dicho (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Choques El Príncipe (TV14) Fútbol Central Fútbol Choques El Príncipe (TV14) Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl On the Psychiatrist’s Couch With Daniel Amen, MD San Diego: Above 52 KVEA Paid Program Enfoque Haywire (R) 56 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up J. -

WWE Battleground/Seth Rollins Predictions

Is The Future Of Wrestling Now? WWE Battleground/Seth Rollins Predictions Author : When Seth Rollins first stabbed his brothers in “The Shield” in the back, he joined “The Authority” and proclaimed himself the Future of the WWE. Why shouldn’t he … He was on top of the world. He had the protection of Triple H and the rest of the stable, he had the Money in the Bank contract and then, he had the World Title. With the Championship came a bit of hubris for Rollins. That Hubris has caused him to alienate all who have been around to help him and protect him. He had made up with them before his big title match with Brock Lesnar at Battleground, giving J&J Security Apple Watches and a brand new Cadillac, and he gave Kane an Apple Watch and a trip to Hawaii. It seemed to work as they ALL had Rollin’s back when Lesnar showed up on RAW. But all that did was piss off the Beast. Lesnar then went and tore apart the Caddy and had it junked. While he was doing that he broke Jamie Noble’s arm and suplexed Joey Mercury through the windshield, putting them both out of action. Then last week on RAW, Lesnar dropped the steel steps on Kane’s ankle. That pissed Rollins off so much; he then yelled at Kane and jumped on his ankle. So you can cross off the Devil’s favorite Demon off of Rollins protection list heading into Battleground. So what IS going to happen to the “Future” of the WWE? Here is one mans informed opinion.