Environmental Standards, Thresholds, and the Next Battleground of Climate Change Regulations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unintended Consequences of the American Presidential Selection System

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLP\15-1\HLP104.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-JUL-21 12:54 The Best Laid Plans: Unintended Consequences of the American Presidential Selection System Samuel S.-H. Wang and Jacob S. Canter* The mechanism for selecting the President of the United States, the Electoral College, causes outcomes that weaken American democracy and that the delegates at the Constitu- tional Convention never intended. The core selection process described in Article II, Section 1 was hastily drawn in the final days of the Convention based on compromises made originally to benefit slave-owning states and states with smaller populations. The system was also drafted to have electors deliberate and then choose the President in an age when travel and news took weeks or longer to cross the new country. In the four decades after ratification, the Electoral College was modified further to reach its current form, which includes most states using a winner-take-all method to allocate electors. The original needs this system was designed to address have now disappeared. But the persistence of these Electoral College mechanisms still causes severe unanticipated problems, including (1) con- tradictions between the electoral vote winner and national popular vote winner, (2) a “battleground state” phenomenon where all but a handful of states are safe for one political party or the other, (3) representational and policy benefits that citizens in only some states receive, (4) a decrease in the political power of non-battleground demographic groups, and (5) vulnerability of elections to interference. These outcomes will not go away without intervention. -

The Popular Culture Studies Journal

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor Kevin Calcamp Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Wrestling” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of https://openclipart.org EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH FALON DEIMLER Minnesota State University, Moorhead University of Wisconsin-Madison JESSICA AUSTIN HANNAH DODD Anglia Ruskin University The Ohio State University AARON BARLOW ASHLEY M. DONNELLY New York City College of Technology (CUNY) Ball State University Faculty Editor, Academe, the magazine of the AAUP JOSEF BENSON LEIGH H. EDWARDS University of Wisconsin Parkside Florida State University PAUL BOOTH VICTOR EVANS DePaul University Seattle University GARY BURNS JUSTIN GARCIA Northern Illinois University Millersville University KELLI S. BURNS ALEXANDRA GARNER University of South Florida Bowling Green State University ANNE M. CANAVAN MATTHEW HALE Salt Lake Community College Indiana University, Bloomington ERIN MAE CLARK NICOLE HAMMOND Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota University of California, Santa Cruz BRIAN COGAN ART HERBIG Molloy College Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne JARED JOHNSON ANDREW F. HERRMANN Thiel College East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO MATTHEW NICOSIA Maryville University of St. -

Spreading the Gospel of Climate Change: an Evangelical Battleground

NEW POLITICAL REFORM NEW MODELS OF AMERICA PROGRAM POLICY CHANGE LYDIA BEAN AND STEVE TELES SPREADING THE GOSPEL OF CLIMATE CHANGE: AN EVANGELICAL BATTLEGROUND PART OF NEW AMERICA’S STRANGE BEDFELLOWS SERIES NOVEMBER 2015 #STRANGEBEDFELLOWS About the Authors About New Models of Policy Change Lydia Bean is author of The Politics New Models of Policy Change starts from the observation of Evangelical Identity (Princeton UP that the traditional model of foundation-funded, 2014). She is Executive Director of Faith think-tank driven policy change -- ideas emerge from in Texas, and Senior Consultant to the disinterested “experts” and partisan elites compromise PICO National Network. for the good of the nation -- is failing. Partisan polarization, technological empowerment of citizens, and heightened suspicions of institutions have all taken their toll. Steven Teles is an associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins But amid much stagnation, interesting policy change University and a fellow at New America. is still happening. The paths taken on issues from sentencing reform to changes in Pentagon spending to resistance to government surveillance share a common thread: they were all a result of transpartisan cooperation. About New America By transpartisan, we mean an approach to advocacy in which, rather than emerging from political elites at the New America is dedicated to the renewal of American center, new policy ideas emerge from unlikely corners of politics, prosperity, and purpose in the Digital Age. We the right or left and find allies on the other side, who may carry out our mission as a nonprofit civic enterprise: an come to the same idea from a very different worldview. -

The Atlantic Return and the Payback of Evangelization

Vol. 3, no. 2 (2013), 207-221 | URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-114482 The Atlantic Return and the Payback of Evangelization VALENTINA NAPOLITANO* Abstract This article explores Catholic, transnational Latin American migration to Rome as a gendered and ethnicized Atlantic Return, which is figured as a source of ‘new blood’ that fortifies the Catholic Church but which also profoundly unset- tles it. I analyze this Atlantic Return as an angle on the affective force of his- tory in critical relation to two main sources: Diego Von Vacano’s reading of the work of Bartolomeo de las Casas, a 16th-century Spanish Dominican friar; and to Nelson Maldonado-Torres’ notion of the ‘coloniality of being’ which he suggests has operated in Atlantic relations as enduring and present forms of racial de-humanization. In his view this latter can be counterbalanced by embracing an economy of the gift understood as gendered. However, I argue that in the light of a contemporary payback of evangelization related to the original ‘gift of faith’ to the Americas, this economy of the gift is less liberatory than Maldonado-Torres imagines, and instead part of a polyfaceted reproduc- tion of a postsecular neoliberal affective, and gendered labour regime. Keywords Transnational migration; Catholicism; economy of the gift; de Certeau; Atlantic Return; Latin America; Rome. Author affiliation Valentina Napolitano is an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthro- pology and the Director of the Latin American Studies Program, University of *Correspondence: Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, 19 Russell St., Toronto, M5S 2S2, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (3.0) Religion and Gender | ISSN: 1878-5417 | www.religionandgender.org | Igitur publishing Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 10:21:12AM via free access Napolitano: The Atlantic Return and the Payback of Evangelization Toronto. -

Neutral Ground Or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston American Studies Faculty Publication Series American Studies 2018 Neutral Ground or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter Lynnell L. Thomas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/amst_faculty_pubs Part of the African American Studies Commons, Africana Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, and the Tourism Commons Neutral Ground or Battleground? Hidden History, Tourism, and Spatial (In)Justice in the New Orleans French Quarter Lynnell L. Thomas The National Slave Ship Museum will be the next great attraction for visitors and locals to experience. It will reconnect Americans to their complicated and rich history and provide a neutral ground for all of us to examine the costs of our country’s development. —LaToya Cantrell, New Orleans councilmember, 20151 In 2017, the city of New Orleans removed four monuments that paid homage to the city’s Confederate past. The removal came after contentious public de- bate and decades of intermittent grassroots protests. Despite the public process, details about the removal were closely guarded in the wake of death threats, vandalism, lawsuits, and organized resistance by monument supporters. Work- Lynnell L. Thomas is Associate Professor of American Studies at University of Massachusetts Boston. Research for this article was made possible by a grant from the College of the Liberal Arts Dean’s Research Fund, University of Massachusetts Boston. I would also like to thank Leon Waters for agreeing to be interviewed for this article. 1. In 2017, Cantrell was elected mayor of New Orleans; see “LaToya Cantrell Elected New Or- leans’ First Female Mayor,” http://www.nola.com/elections/index.ssf/2017/11/latoya_cantrell _elected_new_or.html. -

Funding Report

PROGRAMS I STATE CASH FLOW * R FED CASH FLOW * COMPARE REPORT U INTRASTATE * LOOPS * UNFUNDED * FEASIBILITY * DIVISION 7 TYPE OF WORK / ESTIMATED COST IN THOUSANDS / PROJECT BREAK TOTAL PRIOR STATE TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM PROJ YEARS 5 YEAR WORK PROGRAM DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRAM "UNFUNDED" LOCATION / DESCRIPTION COST COST FUNDING ID (LENGTH) ROUTE/CITY COUNTY NUMBER (THOU) (THOU) SOURCE FY 2009 FY 2010 FY 2011 FY 2012 FY 2013 FY 2014 FY 2015 FY 2016 FY 2017 FY 2018 FY 2019 FY 2020 FUTURE YEARS 2011-2020 Draft TIP (August 2010) I-40/85 ALAMANCE I-4714 NC 49 (MILE POST 145) TO NC 54 (MILE 7551 7551 IMPM CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 POST 148). MILL AND RESURFACE. (2.8 MILES) 2009-2015 TIP (June 2008) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $4.4 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 I-40/85 ALAMANCE I-4714 NC 49 (MILEPOST 145) TO NC 54 (MILEPOST 5898 869 IMPM CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 479 CG 1676 148). MILL AND RESURFACE. (2.8 MILES) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $4.4 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 2011-2020 Draft TIP (August 2010) I-40/I-85 ALAMANCE I-4918 NC 54 (MILE POST 148) IN ALAMANCE COUNTY 9361 9361 IMPM CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 TO WEST OF SR 1114 (BUCKHORN ROAD) IN ORANGE ORANGE COUNTY. MILL AND RESURFACE. (8.3 MILES) 2009-2015 TIP (June 2008) PROJECT COMPLETE - GARVEE BOND FUNDING $12.0 MILLION; PAYBACK FY 2007 - FY 2018 I-40/I-85 ALAMANCE I-4918 NC 54 (MILEPOST 148) IN ALAMANCE COUNTY 15906 2120 IMPM CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 1313 CG 4595 TO WEST OF SR 1114 (BUCKHORN ROAD) IN ORANGE ORANGE COUNTY. -

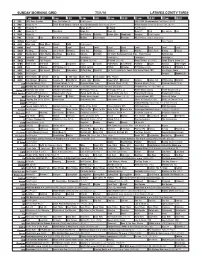

Sunday Morning Grid 7/31/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/31/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program 2016 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å 2016 Ricoh Women’s British Open Championship Final Round. (N) Å Action Sports From Long Beach, Calif. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Pregame MLS Soccer: Timbers at Sporting 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Mom Mkver Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Eat Dirt-Axe 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program El Chavo (N) (TVG) Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (N) (TV14) Como Dice el Dicho (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Choques El Príncipe (TV14) Fútbol Central Fútbol Choques El Príncipe (TV14) Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl On the Psychiatrist’s Couch With Daniel Amen, MD San Diego: Above 52 KVEA Paid Program Enfoque Haywire (R) 56 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up J. -

WWE Battleground/Seth Rollins Predictions

Is The Future Of Wrestling Now? WWE Battleground/Seth Rollins Predictions Author : When Seth Rollins first stabbed his brothers in “The Shield” in the back, he joined “The Authority” and proclaimed himself the Future of the WWE. Why shouldn’t he … He was on top of the world. He had the protection of Triple H and the rest of the stable, he had the Money in the Bank contract and then, he had the World Title. With the Championship came a bit of hubris for Rollins. That Hubris has caused him to alienate all who have been around to help him and protect him. He had made up with them before his big title match with Brock Lesnar at Battleground, giving J&J Security Apple Watches and a brand new Cadillac, and he gave Kane an Apple Watch and a trip to Hawaii. It seemed to work as they ALL had Rollin’s back when Lesnar showed up on RAW. But all that did was piss off the Beast. Lesnar then went and tore apart the Caddy and had it junked. While he was doing that he broke Jamie Noble’s arm and suplexed Joey Mercury through the windshield, putting them both out of action. Then last week on RAW, Lesnar dropped the steel steps on Kane’s ankle. That pissed Rollins off so much; he then yelled at Kane and jumped on his ankle. So you can cross off the Devil’s favorite Demon off of Rollins protection list heading into Battleground. So what IS going to happen to the “Future” of the WWE? Here is one mans informed opinion. -

'Battleground' to Be Aired in 'Suplex City'?

‘Battleground’ to be aired in ‘Suplex City’? “With a pinfall victory on the challenger and not on the champion”, like the representative Paul Heyman for his client Brock Lesnar likes to put it, started the WWE World Heavyweight Championship reign of Seth Rollins this past March and is lasting till today. Despite winning the most prestigious trophy on the grandest stage of them all at Wrestlemania 31, Seth Rollins has made himself a much bigger enemy naming Brock Lesnar. Brock Lesnar, the men with the most feared and intimidating physic and attitude, who likes to settle his scores in his own painful way, that mostly leads to physical damage of any human being, who is voluntarily or inadvertently blocking the path of this dangerous creature. He is been called the Beast Incarnate and unceremoniously it is the best way to describe the endangerment coming from this men. But ever since losing the WWE World Heavyweight Championship at this year’s Wrestlemania in screwing fashion, Brock Lesnar has released and publicly displayed his frustration to higher plateaus. Superstars like Joe Mercury and Jamie Nobel (J&J Security), Kane (Director of Operations) and many more already got victimized by Brock Lesnar and suffered broken body parts and multiple surgeries. In fact the only Superstar he hasn’t got his hands on already is the current Champion Seth Rollins, who is called the Architect or the man, who never fails in elaborating a master plan, which aids him to push his career to greater levels. However to push his career this time, he needs to outperform and outsmart the obstacle Brock Lesnar, who will stop at nothing to deliver series of Back Suplexes, which will immediately put Seth Rollins to ‘Suplex City’, to ensure he won’t achieve his goal again. -

1/2013 Update on Security and Human Rights Issues in South-Central

1/2013 ENG Update on security and human rights issues in South-Central Somalia, including in Mogadishu Joint report from the Danish Immigration Service’s and the Norwegian Landinfo’s fact finding mission to Nairobi, Kenya and Mogadishu, Somalia 17 to 28 October 2012 Copenhagen, January 2013 LANDINFO Danish Immigration Service Storgata 33a, PB 8108 Dep. Ryesgade 53 0032 Oslo 2100 Copenhagen Ø Phone: +47 23 30 94 70 Phone: 00 45 35 36 66 00 Web: www.landinfo.no Web: www.newtodenmark.dk E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Security and human rights issues in S-C Somalia, including Mogadishu Contents Introduction and disclaimer ................................................................................................................. 5 1 Overview of political developments since February 2012 ................................................................ 7 2 Military and security developments in Mogadishu ......................................................................... 12 2.1 Level of fighting in Mogadishu ............................................................................................... 12 2.1.1 Security situation for civilians in Mogadishu ................................................................... 15 Property and land issues ......................................................................................................... 20 2.1.2 Civilian casualties and violations ...................................................................................... 20 2.1.3 Presence of international -

Women's Bodies As a Battleground

Women’s Bodies as a Battleground: Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls During the War in the Democratic Republic of Congo South Kivu (1996-2003) Réseau des Femmes pour un Développement Associatif Réseau des Femmes pour la Défense des Droits et la Paix International Alert 2005 Réseau des Femmes pour un Développement Associatif (RFDA), Réseau des Femmes pour la Défense des Droits et la Paix (RFDP) and International Alert The Réseau des Femmes pour un Développement Associatif and the Réseau des Femmes pour la Défense des Droits et la Paix are based in Uvira and Bukavu respectively in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Both organisations have developed programmes on the issue of sexual violence, which include lobbying activities and the provision of support to women and girls that have been victims of this violence. The two organisations are in the process of creating a database concerning violations of women’s human rights. RFDA has opened several women’s refuges in Uvira, while RFDP, which is a founder member of the Coalition Contre les Violences Sexuelles en RDC (Coalition Against Sexual Violence in the DRC) is involved in advocacy work targeting the United Nations, national institutions and local administrative authorities in order to ensure the protection of vulnerable civilian populations in South Kivu, and in par- ticular the protection of women and their families. International Alert, a non-governmental organisation based in London, UK, works for the prevention and resolution of conflicts. It has been working in the Great Lakes region since 1995 and has established a programme there supporting women’s organisations dedicated to building peace and promoting women’s human rights. -

The Information Battleground: Terrorist Violence and the Role of the Media 291

The Information CHAPTER 11 Battleground Terrorist Violence and the Role of the Media distribute or OPENING VIEWPOINT: MEDIA-ORIENTED TERROR ANDpost, LEBANON’S HEZBOLLAH Lebanon’s Hezbollah has long engaged in media-oriented politi- Hezbollah’s attacks against the Israelis in South Lebanon were cal violence. In the aftermath of its attacks, Hezbollah leaders videotaped and sent to the media—with images of dead Israeli and supporters—sometimes including the influential Lebanese soldiers and stalwart Hezbollah attackers. Sunni Amal militia—engaged in public relations campaigns. copy,Young Hezbollah suicide bombers recorded videotaped Press releases were issued and interviews granted. Statements messages prior to their attacks. These messages explained in were made to the world press claiming, for example, that attacks very patriotic terms why they intended to attack Israeli interests against French and U.S. interests were in reprisal fornot their sup- as human bombs. These tapes were widely distributed, and port of the Lebanese Christian Phalangist militia and the Israelis. the suicidal fighters were cast as martyrs in a righteous cause. This public linkage between terrorist attacks and a seemingly Photographs and other likenesses of many Hezbollah “martyrs” noble cause served to spin the violence favorablyDo and thereby have been prominently displayed in Hezbollah-controlled areas. justify it. - Hezbollah continues to maintain an extensive media and Hezbollah intentionally packaged its strikes as represent- public relations operation and has an active website. The web- ing heroic resistance against inveterate evil and exploitation. site contains a great deal of pro-Hezbollah information, includ- They produced audio, photographic, and video images of their ing political statements, reports from the “front,” audio links, resistance for distribution to the press.