Wandering Writers in the Himalaya: Contesting Narratives and Renunciation in Modern Hindi Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Changing Ideas of Freedom in the Indian Postcolonial Context

IDEALISM, ENCHANTMENT AND DISENCHANTMENT: CHANGING IDEAS OF FREEDOM IN THE INDIAN POSTCOLONIAL CONTEXT Yamini Worldwide, Colonial and Postcolonial Literature has represented processes of nation-formation and concepts of nationalism through experiments with forms of representation. Such experiments were quite predominant in the novel form, with its ability to incorporate vast spatial and temporal realities. Homi Bhabha’s Nation and Narration (2008) is a seminal volume discussing the innovations in the Twentieth Century Novel through a Postcolonial perspective and understanding these changes through the idea of National Literatures. The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Literary Studies (Neil Lazarus) and The Post-Colonial Studies Reader (Bill Ashcroft et al) present extensive discussions on the relationship between the politics of nation-formation and forms of fiction. In this article I offer a brief introduction to the evolution of the Hindi novel (1940s-1980s) with reference to the freedom movement and nationalist struggle in India. Benedict Anderson’s formulation regarding the significance of the genre of the novel in the process of nation-formation and Timothy Brennan’s concept of ‘The National Longing for Form’ published in Nation and Narration also establishes the novel as a genre representing, as well as creating, the Nation. Brennan writes It was the novel that historically accompanied the rise of the nations by objectifying the ‘one, yet many’ of the national life, and by mimicking the structure of the nation, a clearly bordered jumble of languages and styles… Its manner of presentation allowed people to imagine the special community that was the nation (Brennan, 2008: 49). Postcolonial theories have focussed on the relationship between realism and nationalism within the genre of the novel. -

Translation Studies

BACHELOR OF ARTS III YEAR ENGLISH LITERATURE PAPER – II: TRANSLATION STUDIES BHARATHIAR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION COIMBATORE – 641 046. ADDENDUM B.A. English Literature – III year Study material of Paper II – TRANSLATION STUDES SL. No. Page No. Corrections Carried Over 1 -- Add the subject “Application of Translation in Tirukkural and the Odyssey” in Unit – V of the syllabus. 2. -- Add reference (16) Sri V.V.S. Aiyar. 2005. Tirukkural: English Translation. Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam, (17) Homer – Allen Mandelbaum – Roman Maria Luisa – De. 1990. The Odyssey of Homer: a new verse translation. University of California Press. 3. 132 Add in Lesson – V – Place of Style in Translation under Unit-V. (f) Application of Translation in Tirukkural and the Odyssey. 4. 158 Add the title under Unit-V Annexure –I (i) Tirukkural (ii) The Odyssey Paper – II: TRANSLATION STUDIES Syllabus Objectives: The course is intended to initiate the student to the translation discipline, its chronological history and provide a better understanding of the different types of translations as well as its various theories and applications. It further aims to equip the student with a proper knowledge of the aspects of creative literature, the function of Mass media in society and the various issues involved in translation. Unit – I: History of Translation Nature of translation studies – The Function of language – Structuralist Theory and Application – Translation through the ages – Dryden’s classification of translation models. Unit – II: Theories of Translation Types of translation – Translation theories: Ancient and Modern – Nida’s three base models of translation – (Nida’s model Cont...)Transfer and Restructuring – Linguistics of translation. -

Role of Translation in Comparative Literature

Role of Translation in Comparative Literature Surjeet Singh Warwal Abstract In today’s world Translation is getting more and more popularity. There are many reasons behind it. The first and the foremost reason is that it contributes to the unity of nations. It also encourages mutual understanding, broad-mindedness, cultural dialogues and intertextuality. But one can hardly think of comparative literature without immediate thinking of translation. For instance most readers in India know the works of Goethe, Tolstoy, Balzac, Shakespeare and Gorky only through translation. It is through the intermediary of translator that we get access to other literatures. Thus Comparative Literature and translation humanize relationship between people and nations. As an intermediary between languages, thoughts and cultures, they contribute to the respect of difference and alterability. Moreover, they unite the self and the other in their truths, myths, force and weakness. From a historical perspective, comparative literature and translation have always been complementary. Without the help of translation a normal person, who usually knows two to three languages would never have known the universal masterpieces of Dante, Shakespeare, Borges, Kalidas, and Cervantes etc. A normal person usually may not know more than two-three languages. But if s/he wanted to study and compare the literature of two or more languages s/he must be familiar with those languages and cultures. If s/he does not know any of these languages s/he can take help of translation. Those texts might be translated by someone else who knows that language and the comparativist can use that translated text to solve his/her purpose. -

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Prabhakar Machwe Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Dr. Prabhakar Machwe (1917-1991) Prolific writer, linguist and an authority on Indian literature, Dr. Prabhakar Machwe was born on 26 December 1917 at Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India. He graduated from Vikram University, Ujjain and obtained Masters in Philosophy, 1937, and English Literature, 1945, Agra University; Sahitya Ratna and Ph.D, Agra University, 1957. Dr. Machwe started his career as a lecturer in Madhav College, Ujjain, 1938-48. He worked as Literary Producer, All India Radio, Nagpur, Allahabad and New Delhi, 1948-54. He was closely associated with Sahitya Akademi from its inception in 1954 and served as Assistant Secretary, 1954-70, and Secretary, 1970-75. Dr. Machwe was Visiting Professor in Indian Studies Departments at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California on a Fulbright and Rockefeller grant (1959-1961); and later Officer on Special Duty (Language) in Union Public Service Commission, 1964-66. After retiring from Sahitya Akademi in 1975, Dr. Machwe was a visiting fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Simla, 1976-77, and Director of Bharatiya Bhasha Parishad, Calcutta, 1979-85. He spent the last years of his life in Indore as Chief Editor of a Hindi daily, Choutha Sansar, 1988-91. Dr. Prabhakar Machwe travelled widely for lecture tours to Germany, Russia, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Japan and Thailand. He organised national and international seminars on the occasion of the birth centenaries of Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo between 1961 and 1972. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abelson, R. “In a crisis, Coke tries to be reassuring.” The New York Times. June 16, 1999, www.nytimes.com/1999/06/16/business/in-a-crisis-coke-tries- to-be-reassuring.html. Achaya, K. T. Indian Food: A Historical Companion. 1994. Oxford University Press. 1998. “After Worms, Company Plans Better Packaging.” The Times of India. October 17, 2003, www.articles.timesofndia.indiatimes.com/2003-10-17/mumbai/ 27187468_1_cadbury-chocolates-milk-chocolates-packaging. Ahmad, Aijaz. In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures. Verso, 1992. Akita, Kimiko. “Bloopers of a Geisha: Male Orientalism and Colonization of Women’s Language.” Women and Language, vol. 32, no. 1, 2009, pp. 12–21. Alam, Fakrul. ““Elective Affnities: Edward Said, Joseph Conrad, and the Global Intellectual.” Studia Neophilologica special issue on “Transnational Conrad”, December, 2012. Ali, Agha Shahid. The Veiled Suite: The Collected Poems, Norton & Company, 2009. Anamika. Interview with Arundhati Subramaniam. “Poetry and the Good Girl Syndrome, an interview with Anamika.” Poeetry International Web. 1st June 2006, http://www.poetryinternationalweb.net/pi/site/cou_article/item/6770/ Poetry-and-the-Good-Girl-Syndrome-an-interview-with-Anamika/en. Ananya Chatterjee, director. Daughters of the 73rd Amendment. Produced by the Institute of Social Sciences, 1999. Anderson, R. H., Bilson, T. K., Law, S. A. and Mitchell, B. M. Universal Access to E-mail: Feasibility and societal implications, RAND, 1995. “Another Tata Nano car catches fre.” The Indian Express, April 7, 2010, www. indianexpress.com/news/another-tata-nano-car-catches-fre/601423/2. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 293 S. Rao Garg and D. -

NATIONAL AWARDS JNANPITH AWARD Year Name Language

NATIONAL AWARDS JNANPITH AWARD he Jnanpith Award, instituted on May 22, 1961, is given for the best creative literary T writing by any Indian citizen in any of the languages included in the VIII schedule of the Constitution of India. From 1982 the award is being given for overall contribution to literature. The award carries a cash price of Rs 2.5 lakh, a citation and a bronze replica of Vagdevi. The first award was given in 1965 . Year Name Language Name of the Work 1965 Shankara Kurup Malayalam Odakkuzhal 1966 Tara Shankar Bandopadhyaya Bengali Ganadevta 1967 Dr. K.V. Puttappa Kannada Sri Ramayana Darshan 1967 Uma Shankar Joshi Gujarati Nishitha 1968 Sumitra Nandan Pant Hindi Chidambara 1969 Firaq Garakpuri Urdu Gul-e-Naghma 1970 Viswanadha Satyanarayana Telugu Ramayana Kalpavrikshamu 1971 Bishnu Dey Bengali Smriti Satta Bhavishyat 1972 Ramdhari Singh Dinakar Hindi Uravasi 1973 Dattatreya Ramachandran Kannada Nakutanti Bendre 1973 Gopinath Mohanty Oriya Mattimatal 1974 Vishnu Sankaram Khanldekar Marathi Yayati 1975 P.V. Akhilandam Tamil Chittrappavai 1976 Asha Purna Devi Bengali Pratham Pratisruti 1977 Kota Shivarama Karanth Kannada Mukajjiya Kanasugalu 1978 S.H. Ajneya Hindi Kitni Navon mein Kitni Bar 1979 Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya Assamese Mrityunjay 1980 S.K. Pottekkat Malayalam Oru Desattinte Katha 1981 Mrs. Amrita Pritam Punjabi Kagaz te Canvas 1982 Mahadevi Varma Hindi Yama 1983 Masti Venkatesa Iyengar Kannada Chikka Veera Rajendra 1984 Takazhi Siva Shankar Pillai Malayalam 1985 Pannalal Patel Gujarati 1986 Sachidanand Rout Roy Oriya 1987 Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar Kusumagraj 1988 Dr. C. Narayana Reddy Telugu Vishwambhara 1989 Qurratulain Hyder Urdu 1990 Prof. Vinayak Kishan Gokak Kannada Bharatha Sindhu Rashmi Year Name Language Name of the Work 1991 Subhas Mukhopadhyay Bengali 1992 Naresh Mehta Hindi 1993 Sitakant Mohapatra Oriya 1994 Prof. -

Krishna Sobti: a Writer Who Radiated Bonhomie

ISSN 2249-4529 www.pintersociety.com VOL: 9, No.: 1, SPRING 2019 GENERAL ESSAY UGC APPROVED (Sr. No.41623) BLIND PEER REVIEWED About Us: http://pintersociety.com/about/ Editorial Board: http://pintersociety.com/editorial-board/ Submission Guidelines: http://pintersociety.com/submission-guidelines/ Call for Papers: http://pintersociety.com/call-for-papers/ All Open Access articles published by LLILJ are available online, with free access, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License as listed on http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Individual users are allowed non-commercial re-use, sharing and reproduction of the content in any medium, with proper citation of the original publication in LLILJ. For commercial re-use or republication permission, please contact [email protected] 2 | Krishna Sobti: A Writer Who Radiated Bonhomie Krishna Sobti: A Writer Who Radiated Bonhomie Lakshmi Kannan Post Master House, Summer Hill, Shimla. That is where I got to know this legendary writer Krishna Sobti, who carried the weight of her name very lightly. Unlike many famous writers who choose to insulate themselves within a space that they claim as exclusive, Krishnaji’s immense zest for life, her interest in people, her genuine interest in the works of other writers, and her gift for finding humour in the most unlikely situations made her a very friendly, warm and caring person who touched our lives in myriad ways. Krishnaji left us on 25th January this year, leaving behind a tangible absence. Of her it can be truly said that she lived her life to the hilt, scripting a magnificent life for herself while illuminating the lives of many others who had the good fortune to know her. -

List of Documentary Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi

Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi (Till Date) S.No. Author Directed by Duration 1. Amrita Pritam (Punjabi) Basu Bhattacharya 60 minutes 2. Akhtar-ul-Iman (Urdu) Saeed Mirza 60 minutes 3. V.K. Gokak (Kannada) Prasanna 60 minutes 4. Takazhi Sivasankara Pillai (Malayalam) M.T. Vasudevan Nair 60 minutes 5. Gopalkrishna Adiga (Kannada) Girish Karnad 60 minutes 6. Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi) Padma Sachdev 60 minutes 7. Balamani Amma (Malayalam) Madhusudanan 27 minutes 8. Vinda Karandikar (Marathi) Nandan Kudhyadi 60 minutes 9. Annada Sankar Ray (Bengali) Budhadev Dasgupta 60 minutes 10. P.T. Narasimhachar (Kannada) Chandrasekhar Kambar 27 minutes 11. Baba Nagarjun (Hindi) Deepak Roy 27 minutes 12. Dharamvir Bharti (Hindi) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 13. D. Jayakanthan (Tamil) Sa. Kandasamy 27 minutes 14. Narayan Surve (Marathi) Dilip Chitre 27 minutes 15. Bhisham Sahni (Hindi) Nandan Kudhyadi 27 minutes 16. Subhash Mukhopadhyay (Bengali) Raja Sen 27 minutes 17. Tarashankar Bandhopadhyay (Bengali) Amiya Chattopadhyay 27 minutes 18. Vijaydan Detha (Rajasthani) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 19. Navakanta Barua (Assamese) Gautam Bora 27 minutes 20. Mulk Raj Anand (English) Suresh Kohli 27 minutes 21. Gopal Chhotray (Oriya) Jugal Debata 27 minutes 22. Qurratulain Hyder (Urdu) Mazhar Q. Kamran 27 minutes 23. U.R. Anantha Murthy (Kannada) Krishna Masadi 27 minutes 24. V.M. Basheer (Malayalam) M.A. Rahman 27 minutes 25. Rajendra Shah (Gujarati) Paresh Naik 27 minutes 26. Ale Ahmed Suroor (Urdu) Anwar Jamal 27 minutes 1 27. Trilochan Shastri (Hindi) Satya Prakash 27 minutes 28. Rehman Rahi (Kashmiri) M.K. Raina 27 minutes 29. Subramaniam Bharati (Tamil) Soudhamini 27 minutes 30. O.V. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI Bhasha Samman Presentation hasha Samman for 2012 were presidential address. Ampareen Lyngdoh, Bconferred upon Narayan Chandra Hon’ble Miniser, was the chief guest and Goswami and Hasu Yasnik for Classical Sylvanus Lamare, as the guest of honour. and Medieval Literature, Sondar Sing K Sreenivasarao in in his welcome Majaw for Khasi literature, Addanda C address stated that Sahitya Akademi is Cariappa and late Mandeera Jaya committed to literatures of officially Appanna for Kodava and Tabu Ram recognized languages has realized that Taid for Mising. the literary treasures outside these Akademi felt that while The Sahitya Akademi Bhasha languages are no less invaluable and no it was necessary to Samman Presentation Ceremony and less worthy of celebration. Hence Bhasha continue to encourage Awardees’ Meet were held on 13 May Samman award was instituted to honour writers and scholars in 2013 at the Soso Tham Auditorium, writers and scholars. Sahitya Akademi languages not formally Shillong wherein the Meghalaya Minister has already published quite a number recognised by the of Urban Affairs, Ampareen Lyngdoh of translations of classics from our Akademi, it therefore, was the chief guest. K Sreenivasarao, bhashas. instituted Bhasha Secretary, Sahitya Akademi delivered the He further said, besides the Samman in 1996 to welcome address. President of Sahitya conferment of sammans every year for be given to writers, Akademi, Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari scholars who have explored enduring scholars, editors, presented the Samman and delivered his significance of medieval literatures to lexicographers, collectors, performers or translators. This Samman include scholars who have done valuable contribution in the field of classical and medieval literature. -

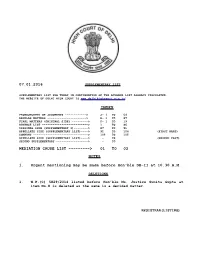

07.01.2016 Mediation Cause List

07.01.2016 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in' INDEX PRONOUNCEMNT OF JUDGMENTS ------------> J- 1 TO 04 REGULAR MATTERS ----------------------> R- 1 TO 87 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ---------> F- 1 TO 19 ADVANCE LIST --------------------------> 1 TO 86 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)--------> 87 TO 91 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 92 TO 104 (FIRST PART) COMPANY -------------------------------> 105 TO 105 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> - TO (SECOND PART) SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY ------------------> - TO MEDIATION CAUSE LIST ---------> 01 TO 03 NOTES 1. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-II at 10.30 A.M. DELETIONS 1. W.P.(C) 5829/2014 listed before Hon'ble Ms. Justice Sunita Gupta at item No.8 is deleted as the same is a decided matter. REGISTRAR(LISTING) 07.01.2016 J-1 PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENT (APPLT. JURISTICTION) COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE JAYANT NATH AT 10.30 A.M 1. W.P.(C) 1524/2015 PRASHANT BHUSHAN JAYANT BHUSHAN, PRANAV SACHDEVA VS. UNION OF INDIA & ANR. NEHA RATHI, SANJAY JAIN ANURAG AHLUWALIA, AKASH NAGAR PALLAVI SHALI 2. W.P.(C) 5472/2014 ASHFAQUE ANSARI V. SHEKHAR, MD. AZAM ANSARI CM APPL. 10868-69/2014 VS. UNION OF INDIA & ORS. SOUMO PALIT, RICHA SHARMA CM APPL. 12873/2015 NISHANT ANAND, B.S. SHUKLA CM APPL. 16579/2015 SHUBHRA PARASHAR, ASHOK MAHAJAN , 3. LPA 540/2015 ACN COLLEGE OF PHARMACY KIRTI UPPAL, CHANDRASHEKAR VS. ALL INDIA COUNCIL SIDDHARTH CHOPRA, ANIL SONI FOR TECHNICAL EDUCATION NAGINDER BENIPAL 4. -

Department of Hindi School of Indian Languages University of Kerala

DEPARTMENT OF HINDI SCHOOL OF INDIAN LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY OF KERALA KARIAVATTOM CAMPUS THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 581, KERALA, INDIA M.Phil PROGRAMME IN HINDI SYLLABUS (Under Credit and Semester System with effect from 2016 Admissions) DEPARTMENT OF HINDI SCHOOL OF INDIAN LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY OF KERALA KARIAVATTOM CAMPUS THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 581, KERALA, INDIA M.Phil PROGRAMME IN HINDI PROGRAMME OBJECTIVES • To acquire deep knowledge in Hindi literature . • Making the students capable in research . • To give training to students to for better approach to research . • To introduce the researchers to various dimensions of research in Hindi Language and literature . • To make the students acquaint with modern trends of Hindi literature . in research . • To make the students enable in the activities pertaining to the research process. STRUCTURE OF THE PROGRAMME Seme Course Name of the Course No. Of Credits ster Code HIN – Research Methodology 4 711 I HIN – Modern literary thoughts and post- 4 712 independence period HIN – Comparative Literature 4 713(i) HIN – Teaching of Hindi Language and 713(ii) Literature HIN – Hindi Movement and Hindi Literature 713(iii) of South India with special Reference to Kerala HIN – Stylistics 713(iv) HIN – Indian Literature –Bhakti 713(v) Movement II HIN – Dissertation 20 721 TOTAL CREDITS 32 Semester :1 Course Code : HIN-711 Course Title : RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Credits : 4 Aim : To enhance the students to areas of creative thinking and critical reasoning in the current issues. Objectives: This course comprises of the activities pertaining to the research process and lectures enabling the formulation of hypothesis COURSE CONTENTS Module I : Research Culture And Aptitude What is research? Words used in Hindi for “Research“, their meaning and appropriateness .