India Progressive Writers Association; *7:Arxicm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Changing Ideas of Freedom in the Indian Postcolonial Context

IDEALISM, ENCHANTMENT AND DISENCHANTMENT: CHANGING IDEAS OF FREEDOM IN THE INDIAN POSTCOLONIAL CONTEXT Yamini Worldwide, Colonial and Postcolonial Literature has represented processes of nation-formation and concepts of nationalism through experiments with forms of representation. Such experiments were quite predominant in the novel form, with its ability to incorporate vast spatial and temporal realities. Homi Bhabha’s Nation and Narration (2008) is a seminal volume discussing the innovations in the Twentieth Century Novel through a Postcolonial perspective and understanding these changes through the idea of National Literatures. The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Literary Studies (Neil Lazarus) and The Post-Colonial Studies Reader (Bill Ashcroft et al) present extensive discussions on the relationship between the politics of nation-formation and forms of fiction. In this article I offer a brief introduction to the evolution of the Hindi novel (1940s-1980s) with reference to the freedom movement and nationalist struggle in India. Benedict Anderson’s formulation regarding the significance of the genre of the novel in the process of nation-formation and Timothy Brennan’s concept of ‘The National Longing for Form’ published in Nation and Narration also establishes the novel as a genre representing, as well as creating, the Nation. Brennan writes It was the novel that historically accompanied the rise of the nations by objectifying the ‘one, yet many’ of the national life, and by mimicking the structure of the nation, a clearly bordered jumble of languages and styles… Its manner of presentation allowed people to imagine the special community that was the nation (Brennan, 2008: 49). Postcolonial theories have focussed on the relationship between realism and nationalism within the genre of the novel. -

Isymbols of Water and Woman on Selected Examples of Modern Bengali Literature in the Context of Mythological Tradition.*

© Wagadu Volume 3: Spring 2006 Symbols of Water and Woman iSymbols of Water and Woman on Selected Examples of Modern Bengali Literature in the Context of Mythological Tradition.* Blanka Knotková-Čapková As in many archaic mythological concepts, the four basic elements are represented in the Indian mythology as either male or female: air (wind) and fire are male principles, later personified as male deities – Agni and Vāyu; earth and water (river) are female. The metaphorization of woman as Water and Earthii has a strong essentialist aspect; it points to the symbol of the womb, the mysterious feminine source of life, the “cradle and grave”iii or “womb and tomb”, “the Great Mother symbolizing circularity of life and death” (cf. Kalnická, in Wilkoszewska 2001, 107), who also disposes with the ultimate power over life and death. As such, she personifies the female creative and dynamic cosmic energy, śakti. Together with her male counterpart (personified as male God Śiva), she represents the dual image of cosmical unity and harmony. In heterodox śaktism, she is worshipped as the ultimate spiritual principle, not dependent on the male principle; in śivaismiv, she is described as the left part of Śiva’s body. Śaktism also worships śakti in the metonymical image of yoni, the female genitals, the location of the sensual pleasure and the beginning of life (the way to / from the womb).v Some of the mythological personifications of śakti have been partially patriarchalized and “married” to the male Gods; a possible pre-Indo-European concept of an independent motherly deity (whose image was connected with the vegetation cycle, eternal recreation and rebirth). -

Translation Studies

BACHELOR OF ARTS III YEAR ENGLISH LITERATURE PAPER – II: TRANSLATION STUDIES BHARATHIAR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION COIMBATORE – 641 046. ADDENDUM B.A. English Literature – III year Study material of Paper II – TRANSLATION STUDES SL. No. Page No. Corrections Carried Over 1 -- Add the subject “Application of Translation in Tirukkural and the Odyssey” in Unit – V of the syllabus. 2. -- Add reference (16) Sri V.V.S. Aiyar. 2005. Tirukkural: English Translation. Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam, (17) Homer – Allen Mandelbaum – Roman Maria Luisa – De. 1990. The Odyssey of Homer: a new verse translation. University of California Press. 3. 132 Add in Lesson – V – Place of Style in Translation under Unit-V. (f) Application of Translation in Tirukkural and the Odyssey. 4. 158 Add the title under Unit-V Annexure –I (i) Tirukkural (ii) The Odyssey Paper – II: TRANSLATION STUDIES Syllabus Objectives: The course is intended to initiate the student to the translation discipline, its chronological history and provide a better understanding of the different types of translations as well as its various theories and applications. It further aims to equip the student with a proper knowledge of the aspects of creative literature, the function of Mass media in society and the various issues involved in translation. Unit – I: History of Translation Nature of translation studies – The Function of language – Structuralist Theory and Application – Translation through the ages – Dryden’s classification of translation models. Unit – II: Theories of Translation Types of translation – Translation theories: Ancient and Modern – Nida’s three base models of translation – (Nida’s model Cont...)Transfer and Restructuring – Linguistics of translation. -

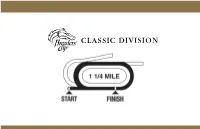

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

Role of Translation in Comparative Literature

Role of Translation in Comparative Literature Surjeet Singh Warwal Abstract In today’s world Translation is getting more and more popularity. There are many reasons behind it. The first and the foremost reason is that it contributes to the unity of nations. It also encourages mutual understanding, broad-mindedness, cultural dialogues and intertextuality. But one can hardly think of comparative literature without immediate thinking of translation. For instance most readers in India know the works of Goethe, Tolstoy, Balzac, Shakespeare and Gorky only through translation. It is through the intermediary of translator that we get access to other literatures. Thus Comparative Literature and translation humanize relationship between people and nations. As an intermediary between languages, thoughts and cultures, they contribute to the respect of difference and alterability. Moreover, they unite the self and the other in their truths, myths, force and weakness. From a historical perspective, comparative literature and translation have always been complementary. Without the help of translation a normal person, who usually knows two to three languages would never have known the universal masterpieces of Dante, Shakespeare, Borges, Kalidas, and Cervantes etc. A normal person usually may not know more than two-three languages. But if s/he wanted to study and compare the literature of two or more languages s/he must be familiar with those languages and cultures. If s/he does not know any of these languages s/he can take help of translation. Those texts might be translated by someone else who knows that language and the comparativist can use that translated text to solve his/her purpose. -

Literary Criticism and Literary Historiography University Faculty

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected]) Title Prof./Dr./Mr./Ms. First Name Ali Last Name Javed Photograph Designation Reader/Associate Professor Department Urdu Address (Campus) Department of Urdu, Faculty of Arts, University of Delhi, Delhi-7 (Residence) C-20, Maurice Nagar, University of Delhi, Delhi-7 Phone No (Campus) 91-011-27666627 (Residence)optional 27662108 Mobile 9868571543 Fax Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. JNU, New Delhi 1983 Thesis topic: British Orientalists and the History of Urdu Literature Topic: Jaafer Zatalli ke Kulliyaat ki M.Phil. JNU, New Delhi 1979 Tadween M.A. JNU, New Delhi 1977 Subjects: Urdu B.A. University of Allahabad 1972 Subjects: English Literature, Economics, Urdu Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role Zakir Husain PG (E) College Lecturer 1983-98 Teaching and research University of Delhi Reader 1998 Teaching and research National Council for Promotion of Director April 2007 to Chief Executive Officer of the Council Urdu Language, HRD, New Delhi December ’08 Research Interests / Specialization Research interests: Literary criticism and literary historiography Teaching Experience ( Subjects/Courses Taught) (a) Post-graduate: 1. History of Urdu Literature 2. Poetry: Ghalib, Josh, Firaq Majaz, Nasir Kazmi 3. Prose: Ratan Nath Sarshar, Mohammed Husain Azad, Sir Syed (b) M. Phil: Literary Criticism Honors & Awards www.du.ac.in Page 1 a. Career Awardee of the UGC (1993). Completed a research project entitled “Impact of Delhi College on the Cultural Life of 19th Century” under the said scheme. -

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Prabhakar Machwe Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Dr. Prabhakar Machwe (1917-1991) Prolific writer, linguist and an authority on Indian literature, Dr. Prabhakar Machwe was born on 26 December 1917 at Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India. He graduated from Vikram University, Ujjain and obtained Masters in Philosophy, 1937, and English Literature, 1945, Agra University; Sahitya Ratna and Ph.D, Agra University, 1957. Dr. Machwe started his career as a lecturer in Madhav College, Ujjain, 1938-48. He worked as Literary Producer, All India Radio, Nagpur, Allahabad and New Delhi, 1948-54. He was closely associated with Sahitya Akademi from its inception in 1954 and served as Assistant Secretary, 1954-70, and Secretary, 1970-75. Dr. Machwe was Visiting Professor in Indian Studies Departments at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California on a Fulbright and Rockefeller grant (1959-1961); and later Officer on Special Duty (Language) in Union Public Service Commission, 1964-66. After retiring from Sahitya Akademi in 1975, Dr. Machwe was a visiting fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Simla, 1976-77, and Director of Bharatiya Bhasha Parishad, Calcutta, 1979-85. He spent the last years of his life in Indore as Chief Editor of a Hindi daily, Choutha Sansar, 1988-91. Dr. Prabhakar Machwe travelled widely for lecture tours to Germany, Russia, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Japan and Thailand. He organised national and international seminars on the occasion of the birth centenaries of Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo between 1961 and 1972. -

World Thoroughbred Racehorse Rankings Conference

EUROPEAN THOROUGHBRED RACEHORSE RANKINGS — 2006 TWO-YEAR-OLDS ICR Kg Age Sex Pedigree Owner Trainer Trained Name 123 55.5 Teofilo (IRE) 2 C Galileo (IRE)--Speirbhean (IRE) Mrs J. S. Bolger J. S. Bolger IRE 122 55.5 Holy Roman Emperor (IRE) 2 C Danehill (USA)--L'On Vite (USA) Mrs John Magnier A. P. O'Brien IRE 121 55 Dutch Art (GB) 2 C Medicean (GB)--Halland Park Lass (IRE) Mrs Susan Roy P. W. Chapple-Hyam GB 119 54 Finsceal Beo (IRE) 2 F Mr Greeley (USA)--Musical Treat (IRE) M. A. Ryan J. S. Bolger IRE Mount Nelson (GB) 2 C Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)--Independence (GB) Mr D. Smith, Mrs J. Magnier, Mr M. Tabor A. P. O'Brien IRE 118 53.5 Spirit One (FR) 2 C Anabaa Blue (GB)--Lavayssiere (FR) B. Chehboub P. H. Demercastel FR 117 53 Battle Paint (USA) 2 C Tale of The Cat (USA)--Black Speck (USA) J. Allen Jean Claude Rouget FR Strategic Prince (GB) 2 C Dansili (GB)--Ausherra (USA) H.R.H. Sultan Ahmad Shah P. F. I. Cole GB 116 52.5 Authorized (IRE) 2 C Montjeu (IRE)--Funsie (FR) Saleh Al Homaizi & Imad Al Sagar P. W. Chapple-Hyam GB Captain Marvelous (IRE) 2 C Invincible Spirit (IRE)--Shesasmartlady (IRE) Mr R. J. Arculli B. W. Hills GB Eagle Mountain (GB) 2 C Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)--Masskana (IRE) Mr D. Smith, Mrs J. Magnier, Mr M. Tabor A. P. O'Brien IRE Haatef (USA) 2 C Danzig (USA)--Sayedat Alhadh (USA) Mr Hamdan Al Maktoum K. -

NATIONAL AWARDS JNANPITH AWARD Year Name Language

NATIONAL AWARDS JNANPITH AWARD he Jnanpith Award, instituted on May 22, 1961, is given for the best creative literary T writing by any Indian citizen in any of the languages included in the VIII schedule of the Constitution of India. From 1982 the award is being given for overall contribution to literature. The award carries a cash price of Rs 2.5 lakh, a citation and a bronze replica of Vagdevi. The first award was given in 1965 . Year Name Language Name of the Work 1965 Shankara Kurup Malayalam Odakkuzhal 1966 Tara Shankar Bandopadhyaya Bengali Ganadevta 1967 Dr. K.V. Puttappa Kannada Sri Ramayana Darshan 1967 Uma Shankar Joshi Gujarati Nishitha 1968 Sumitra Nandan Pant Hindi Chidambara 1969 Firaq Garakpuri Urdu Gul-e-Naghma 1970 Viswanadha Satyanarayana Telugu Ramayana Kalpavrikshamu 1971 Bishnu Dey Bengali Smriti Satta Bhavishyat 1972 Ramdhari Singh Dinakar Hindi Uravasi 1973 Dattatreya Ramachandran Kannada Nakutanti Bendre 1973 Gopinath Mohanty Oriya Mattimatal 1974 Vishnu Sankaram Khanldekar Marathi Yayati 1975 P.V. Akhilandam Tamil Chittrappavai 1976 Asha Purna Devi Bengali Pratham Pratisruti 1977 Kota Shivarama Karanth Kannada Mukajjiya Kanasugalu 1978 S.H. Ajneya Hindi Kitni Navon mein Kitni Bar 1979 Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya Assamese Mrityunjay 1980 S.K. Pottekkat Malayalam Oru Desattinte Katha 1981 Mrs. Amrita Pritam Punjabi Kagaz te Canvas 1982 Mahadevi Varma Hindi Yama 1983 Masti Venkatesa Iyengar Kannada Chikka Veera Rajendra 1984 Takazhi Siva Shankar Pillai Malayalam 1985 Pannalal Patel Gujarati 1986 Sachidanand Rout Roy Oriya 1987 Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar Kusumagraj 1988 Dr. C. Narayana Reddy Telugu Vishwambhara 1989 Qurratulain Hyder Urdu 1990 Prof. Vinayak Kishan Gokak Kannada Bharatha Sindhu Rashmi Year Name Language Name of the Work 1991 Subhas Mukhopadhyay Bengali 1992 Naresh Mehta Hindi 1993 Sitakant Mohapatra Oriya 1994 Prof. -

Madhusudan Dutt and the Dilemma of the Early Bengali Theatre Dhrupadi

Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre Dhrupadi Chattopadhyay Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5–34 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk 2016 | The South Asianist 4 (2): 5-34 | pg. 5 Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5-34 Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt, and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre DHRUPADI CHATTOPADHYAY, SNDT University, Mumbai Owing to its colonial tag, Christianity shares an uneasy relationship with literary historiographies of nineteenth-century Bengal: Christianity continues to be treated as a foreign import capable of destabilising the societal matrix. The upper-caste Christian neophytes, often products of the new western education system, took to Christianity to register socio-political dissent. However, given his/her socio-political location, the Christian convert faced a crisis of entitlement: as a convert they faced immediate ostracising from Hindu conservative society, and even as devout western moderns could not partake in the colonizer’s version of selective Christian brotherhood. I argue that Christian convert literature imaginatively uses Hindu mythology as a master-narrative to partake in both these constituencies. This paper turns to the reception aesthetics of an oft forgotten play by Michael Madhusudan Dutt, the father of modern Bengali poetry, to explore the contentious relationship between Christianity and colonial modernity in nineteenth-century Bengal. In particular, Dutt’s deft use of the semantic excess as a result of the overlapping linguistic constituencies of English and Bengali is examined. Further, the paper argues that Dutt consciously situates his text at the crossroads of different receptive constituencies to create what I call ‘layered homogeneities’. -

Media Guide 2020

MEDIA GUIDE 2020 Contents Welcome 05 Minstrel Stakes (Group 2) 54 2020 Fixtures 06 Jebel Ali Racecourse & Stables Anglesey Stakes (Group 3) 56 Race Closing 2020 08 Kilboy Estate Stakes (Group 2) 58 Curragh Records 13 Sapphire Stakes (Group 2) 60 Feature Races 15 Keeneland Phoenix Stakes (Group 1) 62 TRM Equine Nutrition Gladness Stakes (Group 3) 16 Rathasker Stud Phoenix Sprint Stakes (Group 3) 64 TRM Equine Nutrition Alleged Stakes (Group 3) 18 Comer Group International Irish St Leger Trial Stakes (Group 3) 66 Coolmore Camelot Irish EBF Mooresbridge Stakes (Group 2) 20 Royal Whip Stakes (Group 3) 68 Coolmore Mastercraftsman Irish EBF Athasi Stakes (Group 3) 22 Coolmore Galileo Irish EBF Futurity Stakes (Group 2) 70 FBD Hotels and Resorts Marble Hill Stakes (Group 3) 24 A R M Holding Debutante Stakes (Group 2) 72 Tattersalls Irish 2000 Guineas (Group 1) 26 Snow Fairy Fillies' Stakes (Group 3) 74 Weatherbys Ireland Greenlands Stakes (Group 2) 28 Kilcarn Stud Flame Of Tara EBF Stakes (Group 3) 76 Lanwades Stud Stakes (Group 2) 30 Round Tower Stakes (Group 3) 78 Tattersalls Ireland Irish 1000 Guineas (Group 1) 32 Comer Group International Irish St Leger (Group 1) 80 Tattersalls Gold Cup (Group 1) 34 Goffs Vincent O’Brien National Stakes (Group 1) 82 Gallinule Stakes (Group 3) 36 Moyglare Stud Stakes (Group 1) 84 Ballyogan Stakes (Group 3) 38 Derrinstown Stud Flying Five Stakes (Group 1) 86 Dubai Duty Free Irish Derby (Group 1) 40 Moyglare ‘Jewels’ Blandford Stakes (Group 2) 88 Comer Group International Curragh Cup (Group 2) 42 Loughbrown