Standards for Learning Hindi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abelson, R. “In a crisis, Coke tries to be reassuring.” The New York Times. June 16, 1999, www.nytimes.com/1999/06/16/business/in-a-crisis-coke-tries- to-be-reassuring.html. Achaya, K. T. Indian Food: A Historical Companion. 1994. Oxford University Press. 1998. “After Worms, Company Plans Better Packaging.” The Times of India. October 17, 2003, www.articles.timesofndia.indiatimes.com/2003-10-17/mumbai/ 27187468_1_cadbury-chocolates-milk-chocolates-packaging. Ahmad, Aijaz. In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures. Verso, 1992. Akita, Kimiko. “Bloopers of a Geisha: Male Orientalism and Colonization of Women’s Language.” Women and Language, vol. 32, no. 1, 2009, pp. 12–21. Alam, Fakrul. ““Elective Affnities: Edward Said, Joseph Conrad, and the Global Intellectual.” Studia Neophilologica special issue on “Transnational Conrad”, December, 2012. Ali, Agha Shahid. The Veiled Suite: The Collected Poems, Norton & Company, 2009. Anamika. Interview with Arundhati Subramaniam. “Poetry and the Good Girl Syndrome, an interview with Anamika.” Poeetry International Web. 1st June 2006, http://www.poetryinternationalweb.net/pi/site/cou_article/item/6770/ Poetry-and-the-Good-Girl-Syndrome-an-interview-with-Anamika/en. Ananya Chatterjee, director. Daughters of the 73rd Amendment. Produced by the Institute of Social Sciences, 1999. Anderson, R. H., Bilson, T. K., Law, S. A. and Mitchell, B. M. Universal Access to E-mail: Feasibility and societal implications, RAND, 1995. “Another Tata Nano car catches fre.” The Indian Express, April 7, 2010, www. indianexpress.com/news/another-tata-nano-car-catches-fre/601423/2. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 293 S. Rao Garg and D. -

Krishna Sobti: a Writer Who Radiated Bonhomie

ISSN 2249-4529 www.pintersociety.com VOL: 9, No.: 1, SPRING 2019 GENERAL ESSAY UGC APPROVED (Sr. No.41623) BLIND PEER REVIEWED About Us: http://pintersociety.com/about/ Editorial Board: http://pintersociety.com/editorial-board/ Submission Guidelines: http://pintersociety.com/submission-guidelines/ Call for Papers: http://pintersociety.com/call-for-papers/ All Open Access articles published by LLILJ are available online, with free access, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License as listed on http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Individual users are allowed non-commercial re-use, sharing and reproduction of the content in any medium, with proper citation of the original publication in LLILJ. For commercial re-use or republication permission, please contact [email protected] 2 | Krishna Sobti: A Writer Who Radiated Bonhomie Krishna Sobti: A Writer Who Radiated Bonhomie Lakshmi Kannan Post Master House, Summer Hill, Shimla. That is where I got to know this legendary writer Krishna Sobti, who carried the weight of her name very lightly. Unlike many famous writers who choose to insulate themselves within a space that they claim as exclusive, Krishnaji’s immense zest for life, her interest in people, her genuine interest in the works of other writers, and her gift for finding humour in the most unlikely situations made her a very friendly, warm and caring person who touched our lives in myriad ways. Krishnaji left us on 25th January this year, leaving behind a tangible absence. Of her it can be truly said that she lived her life to the hilt, scripting a magnificent life for herself while illuminating the lives of many others who had the good fortune to know her. -

List of Documentary Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi

Films Produced by Sahitya Akademi (Till Date) S.No. Author Directed by Duration 1. Amrita Pritam (Punjabi) Basu Bhattacharya 60 minutes 2. Akhtar-ul-Iman (Urdu) Saeed Mirza 60 minutes 3. V.K. Gokak (Kannada) Prasanna 60 minutes 4. Takazhi Sivasankara Pillai (Malayalam) M.T. Vasudevan Nair 60 minutes 5. Gopalkrishna Adiga (Kannada) Girish Karnad 60 minutes 6. Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi) Padma Sachdev 60 minutes 7. Balamani Amma (Malayalam) Madhusudanan 27 minutes 8. Vinda Karandikar (Marathi) Nandan Kudhyadi 60 minutes 9. Annada Sankar Ray (Bengali) Budhadev Dasgupta 60 minutes 10. P.T. Narasimhachar (Kannada) Chandrasekhar Kambar 27 minutes 11. Baba Nagarjun (Hindi) Deepak Roy 27 minutes 12. Dharamvir Bharti (Hindi) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 13. D. Jayakanthan (Tamil) Sa. Kandasamy 27 minutes 14. Narayan Surve (Marathi) Dilip Chitre 27 minutes 15. Bhisham Sahni (Hindi) Nandan Kudhyadi 27 minutes 16. Subhash Mukhopadhyay (Bengali) Raja Sen 27 minutes 17. Tarashankar Bandhopadhyay (Bengali) Amiya Chattopadhyay 27 minutes 18. Vijaydan Detha (Rajasthani) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 19. Navakanta Barua (Assamese) Gautam Bora 27 minutes 20. Mulk Raj Anand (English) Suresh Kohli 27 minutes 21. Gopal Chhotray (Oriya) Jugal Debata 27 minutes 22. Qurratulain Hyder (Urdu) Mazhar Q. Kamran 27 minutes 23. U.R. Anantha Murthy (Kannada) Krishna Masadi 27 minutes 24. V.M. Basheer (Malayalam) M.A. Rahman 27 minutes 25. Rajendra Shah (Gujarati) Paresh Naik 27 minutes 26. Ale Ahmed Suroor (Urdu) Anwar Jamal 27 minutes 1 27. Trilochan Shastri (Hindi) Satya Prakash 27 minutes 28. Rehman Rahi (Kashmiri) M.K. Raina 27 minutes 29. Subramaniam Bharati (Tamil) Soudhamini 27 minutes 30. O.V. -

Wandering Writers in the Himalaya: Contesting Narratives and Renunciation in Modern Hindi Literature

Cracow Indological Studies vol. XVII (2015) 10.12797/CIS.17.2015.17.04 Nicola Pozza [email protected] (University of Lausanne, Switzerland) Wandering Writers in the Himalaya: Contesting Narratives and Renunciation in Modern Hindi Literature Summary: The Himalayan setting—especially present-day Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand—has fascinated many a writer in India. Journeys, wanderings, and sojourns in the Himalaya by Hindi authors have resulted in many travelogues, as well as in some emblematic short stories of modern Hindi literature. If the environment of the Himalaya and its hill stations has inspired the plot of several fictional writ- ings, the description of the life and traditions of its inhabitants has not been the main focus of these stories. Rather, the Himalayan setting has primarily been used as a nar- rative device to explore and contest the relationship between the mountain world and the intrusive presence of the external world (primarily British colonialism, but also patriarchal Hindu society). Moreover, and despite the anti-conformist approach of the writers selected for this paper (Agyeya, Mohan Rakesh, Nirmal Verma and Krishna Sobti), what mainly emerges from an analysis of their stories is that the Himalayan setting, no matter the way it is described, remains first and foremost a lasting topos for renunciation and liberation. KEYWORDS: Himalaya, Hindi, fiction, wandering, colonialism, modernity, renunci- ation, Agyeya, Nirmal Verma, Mohan Rakesh, Krishna Sobti. Introduction: Himalaya at a glance The Himalaya has been a place of fascination for non-residents since time immemorial and has attracted travellers, monks and pilgrims and itinerant merchants from all over Asia and Europe. -

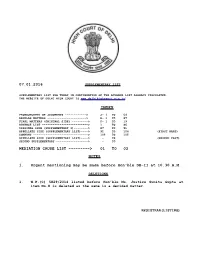

07.01.2016 Mediation Cause List

07.01.2016 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in' INDEX PRONOUNCEMNT OF JUDGMENTS ------------> J- 1 TO 04 REGULAR MATTERS ----------------------> R- 1 TO 87 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ---------> F- 1 TO 19 ADVANCE LIST --------------------------> 1 TO 86 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)--------> 87 TO 91 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 92 TO 104 (FIRST PART) COMPANY -------------------------------> 105 TO 105 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> - TO (SECOND PART) SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY ------------------> - TO MEDIATION CAUSE LIST ---------> 01 TO 03 NOTES 1. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-II at 10.30 A.M. DELETIONS 1. W.P.(C) 5829/2014 listed before Hon'ble Ms. Justice Sunita Gupta at item No.8 is deleted as the same is a decided matter. REGISTRAR(LISTING) 07.01.2016 J-1 PRONOUNCEMENT OF JUDGMENT (APPLT. JURISTICTION) COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE JAYANT NATH AT 10.30 A.M 1. W.P.(C) 1524/2015 PRASHANT BHUSHAN JAYANT BHUSHAN, PRANAV SACHDEVA VS. UNION OF INDIA & ANR. NEHA RATHI, SANJAY JAIN ANURAG AHLUWALIA, AKASH NAGAR PALLAVI SHALI 2. W.P.(C) 5472/2014 ASHFAQUE ANSARI V. SHEKHAR, MD. AZAM ANSARI CM APPL. 10868-69/2014 VS. UNION OF INDIA & ORS. SOUMO PALIT, RICHA SHARMA CM APPL. 12873/2015 NISHANT ANAND, B.S. SHUKLA CM APPL. 16579/2015 SHUBHRA PARASHAR, ASHOK MAHAJAN , 3. LPA 540/2015 ACN COLLEGE OF PHARMACY KIRTI UPPAL, CHANDRASHEKAR VS. ALL INDIA COUNCIL SIDDHARTH CHOPRA, ANIL SONI FOR TECHNICAL EDUCATION NAGINDER BENIPAL 4. -

Postmodern Traces and Recent Hindi Novels

Postmodern Traces and Recent Hindi Novels Veronica Ghirardi University of Turin, Italy Series in Literary Studies Copyright © 2021 Vernon Press, an imprint of Vernon Art and Science Inc, on behalf of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200 C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware, 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Literary Studies Library of Congress Control Number: 2020952110 ISBN: 978-1-62273-880-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press using elements designed by pch.vector / Freepik. To Alessandro & Gabriele If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough Albert Einstein Table of contents Foreword by Richard Delacy ix Language, Literature and the Global Marketplace: The Hindi Novel and Its Reception ix Acknowledgements xxvii Notes on Hindi terms and transliteration xxix Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1. -

100 Questions November 2017

CLATapult Current Affairs Questions – November 2017 1.Who has won coveted “Miss World 2017” crown in China? (a)Alma Andrea Meza (b)Stephanie Hill (c)James Herrell (d)Manushi Chillar 2.Which country crowned the champions of women’s asia 2017 Kabaddi championship after defeating South Korea in Iran ? A. Pakistan B. Japan C. India D. China 3.Who is the president of world bank ? (a) Jim Yong Kim (b) Joaquim Levy (c) Kristalina Georgieva (d) Shaolin Yang 4.Who is the richest person of Asia according to Forbes? (a) Hui Ka Yan (b) Mukesh ambani (c) Ratan Tata (d) Azim Premji 5.Who has been named as india G20 sherpa for the development track of the grouping? (a)Arvind subramanium (b)Neeraj kumar gupta (c)Shaktikanta das (d)Ajay narayan jha 6.Who has been awarded Isarel’s 2018 Genesis prize commonly known as “Jewish Nobel Prize” (a)Angelina jolie (b)Elizebeth taylor (c)Natalie portman (d)Jenifer lowerence 7.Maximum Age of Joining NPS (National Pension Scheme ) is- (a) 60 (b) 65 (c) 67 (d) 62 8.Which place been awarded for UNESCO Asia-Pacific award for cultural heritage conservation? (a)president house (b)The royal opera house (c)Red fort (d)Hotel taj palace 9.Rank of India in WEF Global Gender Gap index – (a) 103 (b) 106 (c) 108 (d) 87 10.Which country is on the top of WEF Global Gender Gap list 2017 ? (a) Finland (b) Iceland (c) Norway (d) China 11.Walmart India launched its first fulfilment centre in which city? (a) Mumbai (b) Bangalore (c) Hyderabad (d) Chandigarh 12.Who has been crowned as “Miss International 2017” in Tokyo? (a)Kevin Lilliana -

TRANSLATING from THESE ’OTHER’ LANGUAGES? Annie Montaut

WHY AND HOW: TRANSLATING FROM THESE ’OTHER’ LANGUAGES? Annie Montaut To cite this version: Annie Montaut. WHY AND HOW: TRANSLATING FROM THESE ’OTHER’ LANGUAGES?. Neeta Gupta. Translating Bharat, Reading India, Yatrabooks, pp.58-71, 2016. halshs-01403683 HAL Id: halshs-01403683 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01403683 Submitted on 27 Nov 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. WHY AND HOW: TRANSLATING FROM THESE ‘OTHER’ LANGUAGES? Annie Montaut he wonder of a Western journalist or literature scholar at Indians writing in ‘regional’ languages T(or ‘vernacular’, or, in India, bhashas) involves an obvious understatement: why don’t you write in English, why such a bizarre inclination towards a medium vaguely perceived as archaic, or smelling of dubious revivalism, or dusty, or naïve, a folk dialect, if you wish to take part in the world dialogue of cultures and belong to the real network of the world story? It is easy to recognize the never-ending ‘orientalist’ (in Said’s meaning) bias, a colonial legacy, behind the persistent asking of the same question to bhasha writers who simply write in their mother tongue, as if English was unquestionably a better literary medium, and regional writers were defined primarily by their linguistic medium, as opposed to writers in the world’s major languages. -

Human Feelings Are Aplenty in These Beautiful Portrayals

INDIA’S KATHA CATALOGUE 2012 MULTICULTURAL IDENTITY THROUGH THE STORIES — THE PIONEER CREATING A GROWING INTEREST IN REGIONAL LITERATURE — THE HINDU HUMAN FEELINGS ARE APLENTY IN THESE BEAUTIFUL PORTRAYALS — THE STATESMAN A SMALL SHARE OF THE REGIONAL GOLD MINE — THE INDIAN EXPRESS AN INSTITUTION IN THE WORLD OF INDIAN LITERATURE — THE BUSINESS STANDARD THE BEST OF INDIA TRANSLATED THE HEART HAS ITS REASONS KRISHNA SOBTI Translated by Reema Anand and Meenakshi Swami Mehak and Kripanarayan’s love story set in 20th century Delhi that stirs up tempestuos passions beneath the simmering calm of family and marriage. Writer par excellence and recipient of the Katha Chudamani and Sahitya Akademi Awards, Sobti’s powerful narratives defy territorial specifics. Katha Hindi Library/Novel 2005 . PB . Rs 250 5.5” x 8” . pp 224 ISBN: 81-87649-54-2 Award-Winning Award-Winning Translated from the Hindi With this book, Katha, true to its reputation as a pioneering Indian translation house of quality, has risen to the challenge. Sobti’s literary craftsmanship surges to the fore in this rendition. We hope Katha will, over time, translate all her works for our benefit, besides this one, and Ei Lakdi, which they rendered earlier. Because a taste of Sobti, either in Hindi or in translation, leaves us yearning for more, much more. — The Hindu THE MAN FROM CHINNAMASTA INDIRA GOSWAMI Translated by Prashanta Goswami Jnanpith Award winner Indira Goswami’s forceful tale about the sects, rituals, practices and beliefs that form part of the Kamakhya legend of Kamrup. Katha Asomiya Library 2006 . PB . Rs 300 5.5” x 8” . -

Feminine Desire Is Human Desire Women Writing Feminism in Postindependence India

Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East Feminine Desire Is Human Desire Women Writing Feminism in Postindependence India Preetha Mani he 1950s and 1960s short stories of the Hindi woman writer Mannu Bhandari (1931 – ) and the Tamil woman writer R. Chudamani (1931 – 2010) candidly portray female characters who possess T the same desires for freedom of sexual expression, economic independence, and human equal- ity as their male partners. Both writers began publishing at a time when few women writers had gained prominence in the Hindi and Tamil literary spheres or were considered to possess the same literary merit as their male contemporaries. Yet despite introducing characters who broke with or challenged social and sexual mores of their time, the two escaped prevalent criticisms that women writers were too didac- tic, social reformist, or sentimental or that they were primarily interested in producing “shock value” or entertainment.1 Bhandari and Chudamani have consistently been published in the same elite venues as canonical Hindi and Tamil male authors and translated and anthologized in nationally and internation- ally circulating volumes of Indian literature and women’s writing.2 Written at a moment of decline in feminist politics and paucity in the production of “literary” women’s writing, what insights might Bhandari’s and Chudamani’s novel articulations of feminine desire offer into how we understand the genealogies of feminism and women’s writing in India? In this article, I suggest that within their historical and geographic contexts, Bhandari and Chudamani broadened the scope of feminist thought and women’s literary expression in the immediate postindependence mo- ment. -

Evaluative Report of Premchand Archives & Literary Center

EVALUATIVE REPORT OF PREMCHAND ARCHIVES & LITERARY CENTER 1. Name of the Department: Jamia’s Premchand Archives & Literary Centre 2. Year of establishment: July, 2004 3. Is the part of a Centre of the University? Yes 4. Names of Programmes offered (UG, PG, M. Phil., Ph. D., Integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D. Sc., D Litt etc.) Supports Research and Study in the field of Humanities, Education and Sociology. It is an Academic Non-Teaching Centre for Research and Reference only 5. Interdisciplinary Programs and Departments involved: Department of English, Department of Hindi, Department of Fine Arts, AJ Kidwai Mass communication Research Centre, 6. Courses in collaboration with other universities, industries, foreign institutions, etc. : Undertakes orientation of participants from National Archives of India 7. Details of programmes discontinued, if any, with reasons NA 8. Examination System: Annual/ Semester/Trimester /Choice Based Credit System NA 9. Participation of the Department in the courses offered by other Departments NA 10. Number of teaching posts sanctioned, filled and actual (Professors/Associate Professors/Asst. Professors/others) S. No. Post Sanctioned Filled Actual (Including CAS & MPS ) 1 Director / Professor one one 1 NON- TEACHING 2 Associate Professors 0 0 0 3 Asst. Professors 0 0 0 11. Faculty profile with name, qualification, designation, area of specialization, experience and research under guidance ACADEMIC NON-TEACHING STAFF 12. List of senior Visiting Fellows, adjunct faculty, emeritus professors etc. NA S. No. Name Qualifi Designation Specializatio No. of No. of Ph.D./M Phil cation n Years of M. Tech / M D Experience students guided for the last four years Awarded In progress 1.