1 Royal Patronage of Jainism. the Myth of Candragupta Maurya and Bhadrabāhu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

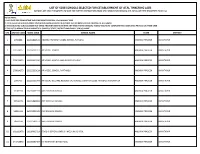

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Julia A. B. Hegewald

Table of Contents 3 JULIA A. B. HEGEWALD JAINA PAINTING AND MANUSCRIPT CULTURE: IN MEMORY OF PAOLO PIANAROSA BERLIN EBVERLAG Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 3 13.04.2015 13:45:43 2 Table of Contents STUDIES IN ASIAN ART AND CULTURE | SAAC VOLUME 3 SERIES EDITOR JULIA A. B. HEGEWALD Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 2 13.04.2015 13:45:42 4 Table of Contents Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographical data is available on the internet at [http://dnb.ddb.de]. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. Coverdesign: Ulf Hegewald. Wall painting from the Jaina Maṭha in Shravanabelgola, Karnataka (Photo: Julia A. B. Hegewald). Overall layout: Rainer Kuhl Copyright ©: EB-Verlag Dr. Brandt Berlin 2015 ISBN: 978-3-86893-174-7 Internet: www.ebverlag.de E-Mail: [email protected] Printed and Hubert & Co., Göttingen bound by: Printed in Germany Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 4 13.04.2015 13:45:43 Table of Contents 7 Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 1 Introduction: Jaina Manuscript Culture and the Pianarosa Library in Bonn Julia A. B. Hegewald ............................................................................ 13 Chapter 2 Studying Jainism: Life and Library of Paolo Pianarosa, Turin Tiziana Ripepi ....................................................................................... 33 Chapter 3 The Multiple Meanings of Manuscripts in Jaina Art and Sacred Space Julia A. -

List of 6038 Schools Selected for Establishment of Atal Tinkering

LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. LAST DATE FOR COMPLETING THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS : 31st JANUARY 2020 2. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST OPEN A NEW BANK ACCOUNT IN A PUBLIC SECTOR BANK FOR THE PURPOSE OF ATL GRANT. 3. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST NOT SHARE THEIR INFORMATION WITH ANY THIRD PARTY/ VENDOR/ AGENT/ AND MUST COMPLETE THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS ON THEIR OWN. 4. THIS LIST IS ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF STATE, DISTRICT AND FINALLY SCHOOL NAME. S.N. ATL UID CODE UDISE CODE SCHOOL NAME STATE DISTRICT 1 2760806 28222800515 ANDHRA PRADESH MODEL SCHOOL PUTLURU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 2 132314217 28224201013 AP MODEL SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 3 574614473 28223600320 AP MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 4 278814373 28223200124 AP MODEL SCHOOL RAPTHADU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 5 2995459 28222500704 AP SOCIAL WELFARE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR GIRLS KURUGUNTA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 6 13701194 28220601919 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 7 15712075 28221890982 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 8 56051196 28222301035 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 9 385c1160 28221591153 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 10 102112978 28220902023 GOOD SHEPHERD ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 11 243715046 28220590484 K C NARAYANA E M SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. -

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Prabhakar Machwe Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Dr. Prabhakar Machwe (1917-1991) Prolific writer, linguist and an authority on Indian literature, Dr. Prabhakar Machwe was born on 26 December 1917 at Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India. He graduated from Vikram University, Ujjain and obtained Masters in Philosophy, 1937, and English Literature, 1945, Agra University; Sahitya Ratna and Ph.D, Agra University, 1957. Dr. Machwe started his career as a lecturer in Madhav College, Ujjain, 1938-48. He worked as Literary Producer, All India Radio, Nagpur, Allahabad and New Delhi, 1948-54. He was closely associated with Sahitya Akademi from its inception in 1954 and served as Assistant Secretary, 1954-70, and Secretary, 1970-75. Dr. Machwe was Visiting Professor in Indian Studies Departments at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California on a Fulbright and Rockefeller grant (1959-1961); and later Officer on Special Duty (Language) in Union Public Service Commission, 1964-66. After retiring from Sahitya Akademi in 1975, Dr. Machwe was a visiting fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Simla, 1976-77, and Director of Bharatiya Bhasha Parishad, Calcutta, 1979-85. He spent the last years of his life in Indore as Chief Editor of a Hindi daily, Choutha Sansar, 1988-91. Dr. Prabhakar Machwe travelled widely for lecture tours to Germany, Russia, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Japan and Thailand. He organised national and international seminars on the occasion of the birth centenaries of Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo between 1961 and 1972. -

Ahimsa and Vegetarianism

March , 2015 Vol. No. 176 Ahimsa Times in World Over + 100000 The Only Jain E-Magazine Community Service for 14 Continuous Years Readership AHIMSA AND VEGETARIANISM MAHARASHTRA GOVERNMENT BANS COW SLAUGHTER: FIVE YEARS JAIL Mar. 3rd, 2015. Mumbai. The bill banning cow slaughter in Maharashtra, pending for several years, finally received the President's assent, which means red meat lovers in the state will have to do without beef. This measure has taken almost twenty years to materialize and was initiated during the previous Sena-BJP Government. The bill was first submitted to the President for approval on January 30, 1996.. However, subsequent Governments at the Centre, including the BJP led NDA stalled it and did not seek the President’s consent. A delegation of seven state BJP MPs led by Kirit Somaiya, (MP from Mumbai North) had met the President in New Delhi recently and submitted a memorandum seeking assent to the bill. The memorandum said that the Maharashtra Animal Preservation (Amendment) Bill, 1995, passed during the previous Shiv Sena-BJP regime, was pending for approval for 19 years. The law will ban beef from the slaughter of bulls and bullocks, which was previously allowed based on a fit- for-slaughter certificate. The new Act will, however, allow the slaughter of water buffaloes. The punishment for the sale of beef or possession of it could be prison for five years with an additional fine of Rs 10,000. It is notable that, Reuters new service had earlier reported that Hindu nationalists in India had stepped up attacks on the country's beef industry, seizing trucks with cattle bound for abattoirs and blockading meat processing plants in a bid to halt the trade in the world's second-biggest exporter of beef. -

Wandering Writers in the Himalaya: Contesting Narratives and Renunciation in Modern Hindi Literature

Cracow Indological Studies vol. XVII (2015) 10.12797/CIS.17.2015.17.04 Nicola Pozza [email protected] (University of Lausanne, Switzerland) Wandering Writers in the Himalaya: Contesting Narratives and Renunciation in Modern Hindi Literature Summary: The Himalayan setting—especially present-day Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand—has fascinated many a writer in India. Journeys, wanderings, and sojourns in the Himalaya by Hindi authors have resulted in many travelogues, as well as in some emblematic short stories of modern Hindi literature. If the environment of the Himalaya and its hill stations has inspired the plot of several fictional writ- ings, the description of the life and traditions of its inhabitants has not been the main focus of these stories. Rather, the Himalayan setting has primarily been used as a nar- rative device to explore and contest the relationship between the mountain world and the intrusive presence of the external world (primarily British colonialism, but also patriarchal Hindu society). Moreover, and despite the anti-conformist approach of the writers selected for this paper (Agyeya, Mohan Rakesh, Nirmal Verma and Krishna Sobti), what mainly emerges from an analysis of their stories is that the Himalayan setting, no matter the way it is described, remains first and foremost a lasting topos for renunciation and liberation. KEYWORDS: Himalaya, Hindi, fiction, wandering, colonialism, modernity, renunci- ation, Agyeya, Nirmal Verma, Mohan Rakesh, Krishna Sobti. Introduction: Himalaya at a glance The Himalaya has been a place of fascination for non-residents since time immemorial and has attracted travellers, monks and pilgrims and itinerant merchants from all over Asia and Europe. -

GONE to the DOGS in ANCIENT INDIA Willem Bollée

GONE TO THE DOGS IN ANCIENT INDIA Willem Bollée Gone to the Dogs in ancient India Willem Bollée Published at CrossAsia-Repository, Heidelberg University Library 2020 Second, revised edition. This book is published under the license “Free access – all rights reserved”. The electronic Open Access version of this work is permanently available on CrossAsia- Repository: http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/ urn: urn:nbn:de:bsz:16-crossasiarep-42439 url: http://crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/4243 doi: http://doi.org/10.11588/xarep.00004243 Text Willem Bollée 2020 Cover illustration: Jodhpur, Dog. Image available at https://pxfuel.com under Creative Commons Zero – CC0 1 Gone to the Dogs in ancient India . Chienne de vie ?* For Johanna and Natascha Wothke In memoriam Kitty and Volpo Homage to you, dogs (TS IV 5,4,r [= 17]) Ο , , ! " #$ s &, ' ( )Plato , * + , 3.50.1 CONTENTS 1. DOGS IN THE INDUS CIVILISATION 2. DOGS IN INDIA IN HISTORICAL TIMES 2.1 Designation 2.2 Kinds of dogs 2.3 Colour of fur 2.4 The parts of the body and their use 2.5 BODILY FUNCTIONS 2.5.1 Nutrition 2.5.2 Excreted substances 2.5.3 Diseases 2.6 Nature and behaviour ( śauvana ; P āli kukkur âkappa, kukkur āna ṃ gaman âkāra ) 2.7 Dogs and other animals 3. CYNANTHROPIC RELATIONS 3.1 General relation 3.1.1 Treatment of dogs by humans 3.1.2 Use of dogs 3.1.2.1 Utensils 3.1.3 Names of dogs 2 3.1.4 Dogs in human names 3.1.5 Dogs in names of other animals 3.1.6 Dogs in place names 3.1.7 Treatment of humans by dogs 3.2 Similes -

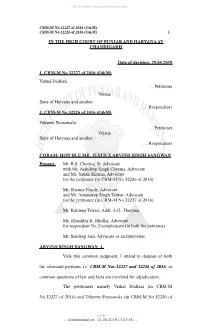

29.04.2019 1. CRM-M No.32227 of 2016 (O&M) Vishal D

Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) CRM-M No.32227 of 2016 (O&M) CRM-M No.32226 of 2016 (O&M) 1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF PUNJAB AND HARYANA AT CHANDIGARH Date of decision: 29.04.2019 1. CRM-M No.32227 of 2016 (O&M) Vishal Dadlani ….Petitioner Versus State of Haryana and another ….Respondents 2. CRM-M No.32226 of 2016 (O&M) Tehseen Poonawala ….Petitioner Versus State of Haryana and another ….Respondents CORAM: HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE ARVIND SINGH SANGWAN Present: Mr. R.S. Cheema, Sr. Advocate with Mr. Arshdeep Singh Cheema, Advocate and Mr. Satish Sharma, Advocate for the petitioner (in CRM-M No.32226 of 2016) Ms. Karuna Nandy, Advocate and Mr. Amandeep Singh Talwar, Advocate for the petitioner (in CRM-M No.32227 of 2016) Mr. Kuldeep Tiwari, Addl. A.G., Haryana. Ms. Khushbir K. Bhullar, Advocate for respondent No.2/complainant (in both the petitions) Mr. Sandeep Jain, Advocate as an Intervener. ARVIND SINGH SANGWAN J. Vide this common judgment, I intend to dispose of both the aforesaid petitions i.e. CRM-M Nos.32227 and 32226 of 2016, as common questions of law and facts are involved for adjudication. The petitioners namely Vishal Dadlani (in CRM-M No.32227 of 2016) and Tehseen Poonawala (in CRM-M No.32226 of 1 of 39 ::: Downloaded on - 01-05-2019 17:47:15 ::: Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) CRM-M No.32227 of 2016 (O&M) CRM-M No.32226 of 2016 (O&M) 2 2016), are arrayed as an accused in the impugned FIR No.0310 dated 28.08.2016 (Annexure P1) registered under Sections 295-A, 153-A and 509 of the Indian Penal Code (in short 'IPC') (Section 66E of the Information Technology Act, 2000 added later) at Police station Ambala Cantt. -

Available Details of Shareholders in Respect of Whom Dividends Remained Unpaid/Unclaimed As on 10/December/2013

Available Details of Shareholders in respect of whom dividends remained unpaid/unclaimed as on 10/December/2013 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husband First Name Father/Husband Father/Husband Last Name Address Country State District PIN Code Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Due Proposed Date of Middle Nme Securities (in Rs.) Transfer to IEPF (DD-MON-YYYY) 2005-06 MANJU BHARGAVA NA NA 2226, MASJID KHAZOOR DHARMPURA DELHI INDIA Delhi 110006 IN30020610269047 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend 3.00 03-Feb-2014 GULSHAN KUMAR GERA NA NA 5/24 A VIJAY NAGAR DOUBLE STOREY DELHI . INDIA Delhi 110009 IN30112715386164 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend 3.00 03-Feb-2014 DESH DEEPAK MALIK NA NA 464 KOHAT ENCLAVE PITAM PURA DELHI INDIA Delhi 110034 IN30094010028042 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend 300.00 03-Feb-2014 RAKESH KUMAR DWIVEDI NA NA F 24/173 SECTOR 3 ROHINI DELHI INDIA Delhi 110085 IN30089610298914 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend 300.00 03-Feb-2014 KISHORE BALANI NA NA A- 321 BLOCK A SECTOR - 19 NOIDA (UP) INDIA Delhi 110091 IN30088813085922 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend 3.00 03-Feb-2014 RAKESH NAGPAL NA NA 912 SECTOR - 9 FARIDABAD HARYANA INDIA Haryana 121006 IN30020610349143 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend 6.00 03-Feb-2014 MANOJ DUNEJA M K DUNEJA K 1/215 N. PALAM VIHAR PHASE-I GURGAON INDIA Haryana 122017 IN30112716604452 Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend 9.00 03-Feb-2014 VEENA JAIN MR SURENDRA JAIN 5 ANANDPURI KANPUR INDIA Uttar Pradesh 208011 IN30055610268520 Amount -

Volume 6, Issue 2 ( VI ) : April - June 2019 Part - 5

Volume 6, Issue 2 (VI) ISSN 2394 - 7780 April - June 2019 International Journal of Advance and Innovative Research (Part - 5) Indian Academicians and Researchers Association www.iaraedu.com International Journal of Advance and Innovative Research Volume 6, Issue 2 ( VI ): April - June 2019 Part - 5 Editor- In-Chief Dr. Tazyn Rahman Members of Editorial Advisory Board Mr. Nakibur Rahman Dr. Mukesh Saxena Ex. General Manager ( Project ) Pro Vice Chancellor, Bongaigoan Refinery, IOC Ltd, Assam University of Technology and Management, Shillong Dr. Alka Agarwal Dr. Archana A. Ghatule Director, Director, Mewar Institute of Management, Ghaziabad SKN Sinhgad Business School, Pandharpur Prof. (Dr.) Sudhansu Ranjan Mohapatra Prof. (Dr.) Monoj Kumar Chowdhury Dean, Faculty of Law, Professor, Department of Business Administration, Sambalpur University, Sambalpur Guahati University, Guwahati Dr. P. Malyadri Prof. (Dr.) Baljeet Singh Hothi Principal, Professor, Government Degree College, Hyderabad Gitarattan International Business School, Delhi Prof.(Dr.) Shareef Hoque Prof. (Dr.) Badiuddin Ahmed Professor, Professor & Head, Department of Commerce, North South University, Bangladesh Maulana Azad Nationl Urdu University, Hyderabad Prof.(Dr.) Michael J. Riordan Dr. Anindita Sharma Professor, Dean & Associate Professor, Sanda University, Jiashan, China Jaipuria School of Business, Indirapuram, Ghaziabad Prof.(Dr.) James Steve Prof. (Dr.) Jose Vargas Hernandez Professor, Research Professor, Fresno Pacific University, California, USA University of Guadalajara,Jalisco, México Prof.(Dr.) Chris Wilson Prof. (Dr.) P. Madhu Sudana Rao Professor, Professor, Curtin University, Singapore Mekelle University, Mekelle, Ethiopia Prof. (Dr.) Amer A. Taqa Prof. (Dr.) Himanshu Pandey Professor, DBS Department, Professor, Department of Mathematics and Statistics University of Mosul, Iraq Gorakhpur University, Gorakhpur Dr. Nurul Fadly Habidin Prof. -

Vol. No. 99 September, 2008 Print "Ahimsa Times "

AHIMSA TIMES - SEPTEMBER 2008 ISSUE - www.jainsamaj.org Page 1 of 22 Vol. No. 99 Print "Ahimsa Times " September, 2008 www.jainsamaj.org Board of Trustees Circulation + 80000 Copies( Jains Only ) Email: Ahimsa Foundation [email protected] New Matrimonial New Members Business Directory PARYUSHAN PARVA Paryushan Parva is an annual religious festival of the Jains. Considered auspicious and sacred, it is observed to deepen the awareness as a physical being in conjunction with spiritual observations Generally, Paryushan Parva falls in the month of September. In Jainisim, fasting is considered as a spiritual activity, that purify our souls, improve morality, spiritual power, increase knowledge and strengthen relationships. The purpose is to purify our souls by staying closer to our own souls, looking at our faults and asking for forgiveness for the mistakes and taking vows to minimize our faults. Also a time when Jains will review their action towards their animals, environment and every kind of soul. Paryashan Parva is an annual, sacred religious festivals of the Jains. It is celebrated with fasting reading of scriptures, observing silence etc preferably under the guidance of monks in temples Strict fasting where one has to completely abstain from food and even water is observed for a week or more. Depending upon one's capability, complete fasting spans between 8-31 days. Religious and spiritual discourses are held where tales of Lord Mahavira are narrated. The Namokar Mantra is chanted everyday. Forgiveness in as important aspect of the celebration. At the end of Fasting, al will ask for forgiveness for any violence or wrong- doings they may have imposed previous year. -

Haryana State Development Report

RYAN HA A Haryana Development Report PLANNING COMMISSION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI Published by ACADEMIC FOUNDATION NEW DELHI First Published in 2009 by e l e c t Academic Foundation x 2 AF 4772-73 / 23 Bharat Ram Road, (23 Ansari Road), Darya Ganj, New Delhi - 110 002 (India). Phones : 23245001 / 02 / 03 / 04. Fax : +91-11-23245005. E-mail : [email protected] www.academicfoundation.com a o m Published under arrangement with : i t x 2 Planning Commission, Government of India, New Delhi. Copyright : Planning Commission, Government of India. Cover-design copyright : Academic Foundation, New Delhi. © 2009. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of, and acknowledgement of the publisher and the copyright holder. Cataloging in Publication Data--DK Courtesy: D.K. Agencies (P) Ltd. <[email protected]> Haryana development report / Planning Commission, Government of India. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 13: 9788171887132 ISBN 10: 8171887139 1. Haryana (India)--Economic conditions. 2. Haryana (India)--Economic policy. 3. Natural resources--India-- Haryana. I. India. Planning Commission. DDC 330.954 558 22 Designed and typeset by Italics India, New Delhi Printed and bound in India. LIST OF TABLES ARYAN 5 H A Core Committee (i) Dr. (Mrs.) Syeda Hameed Chairperson Member, Planning Commission, New Delhi (ii) Smt. Manjulika Gautam Member Senior Adviser (SP-N), Planning Commission, New Delhi (iii) Principal Secretary (Planning Department) Member Government of Haryana, Chandigarh (iv) Prof. Shri Bhagwan Dahiya Member (Co-opted) Director, Institute of Development Studies, Maharshi Dayanand University, Rohtak (v) Dr.