IRS Insights a Closer Look

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20040245547A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2004/0245547 A1 Stipe (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 9, 2004 (54) ULTRA LOW-COST SOLID-STATE MEMORY Publication Classi?cation (75) Inventor; Barry Cushing Stipe, San Jose, CA (51) Int. Cl.7 ................................................ .. H01L 31/109 (Us) (52) US. Cl. ............................................................ .. 257/200 Correspondence Address: (57) ABSTRACT JOSEPH P. CURTIN . A three-dimensional solid-state memory is formed from a plurality of bit lines, a plurality of layers, a plurality of tree ’ structures and a plurality of plate lines. Bit lines extend in a (73) A551 nee, Hitachi Global Stora e Technolo ies ?rst direction in a ?rst plane. Each layer includes an array of g ' B V AZ Amsterdam g memory cells, such as ferroelectric or hysteretic-resistor ' " memory cells. Each tree structure corresponds to a bit line, (21) APPL NO: 10/751 740 has a trunk portion and at least one branch portion. The trunk ’ portion of each tree structure extends from a corresponding (22) Filed; Jam 5, 2004 bit line, and each tree structure corresponds to a plurality of layers. Each branch portion corresponds to at least one layer Related US, Application Data and extends from the trunk portion of a tree structure. Plate lines correspond to at least one layer and overlap the branch (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 10/453,137, portion of each tree structure in at least one roW of tree ?led on Jun. 3, 2003, noW abandoned. structures at a plurality of intersection regions. SRIIIIII DRAM HIIIJ FLASH PROBE GUM MTJ-MRAM 3D-MHAM MATRIX ITFBRIIM GT FERAM 001 size 50F? 012 512 502 502 5F? 002 5e? 512 002 502 Minimum "1" 100m 300m 100m 30 0m 311m 100m 40 nm 400m 10 nm 100m 100m MEX. -

T2 R1.5 Femoral Nailing System

T2 R1.5 Femoral Nailing System Operative Technique Femoral Nailing System Contributing Surgeons Prof. Dr. med. Volker Bühren Chief of Surgical Services Medical Director of Murnau Trauma Center Murnau Germany Joseph D. DiCicco III, D. O. Director Orthopaedic Trauma Service Good Samaritan Hospital Dayton, Ohio Associate Clinical Professor of Orthopeadic Surgery Ohio University and Wright State University USA Thomas G. DiPasquale, D. O. Medical Director, Orthopedic Trauma Services Director, Orthopedic Trauma Fellowship and This publication sets forth detailed Orthopedic Residency Programs recommended procedures for using York Hospital Stryker Osteosynthesis devices and York instruments. USA It offers guidance that you should heed, but, as with any such technical guide, each surgeon must consider the particular needs of each patient and make appropriate adjustments when and as required. A workshop training is required prior to first surgery. All non-sterile devices must be cleaned and sterilized before use. Follow the instructions provided in our reprocessing guide (L24002000). Multi-component instruments must be disassembled for cleaning. Please refer to the corresponding assembly/ disassembly instructions. See package insert (L22000007) for a complete list of potential adverse effects, contraindications, warnings and precautions. The surgeon must discuss all relevant risks, including the finite lifetime of the device, with the patient, when necessary. Warning: Fixation Screws: Stryker Ostreosynthesis bone screws are not approved or intended for screw attachment or fixation to the posterior elements (pedicles) of the cervical, thoracic or lumbar spine. 2 Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 Implant Features 4 Instrument Features 6 References 6 2. Indications, Precautions and Contraindications 7 Indications 7 Precautions 7 Relative Contraindications 7 3. -

Electric Actuators Vsi-1000 Series

ELECTRIC ACTUATORS TM VSI-1000 SERIES DESCRIPTION VSI-1000 Series Electric Actuators are used on Kele KBV Series butterfly valves to provide two-position (with or without battery backup) or proportional control in a NEMA 4X housing. The VSI-1000 Series comes standard on 8" and larger non-spring return assemblies and on 5" and larger two- position spring return assemblies. They can be ordered on smaller valve assemblies as an option. Standard fea- tures include 2 SPDT fully adjustable auxiliary switches KBV-2-6-E2SO (two-position only), manual override crank, and an inter- assembly includes nal heater to prevent condensation in outdoor installa- VSI-BB1020 actuator tions. SPECIFICATIONS FEATURES Power 120 VAC standard •Lightweight, compact design Models 1005 to 1020 12/24 VDC optional • Two-position or modulating control Models 1005 to 1040 24 VAC optional • Two-position battery-backed models Torque range 347-17,359 in-lb • NEMA 4X watertight, corrosion-resistant housing Motor 120 VAC, 1 phase, 60 Hz; • Integral position indicator enclosed, non-ventilated, high • Space heater standard starting torque, reversible induc- • Two 1/2" conduit connections tion, Class E insulation • Detachable manual override crank Thermal overload Auto reset, embedded • Terminal strip wiring Travel limit switches Cam operated, adjustable SPDT • Worm gear drive, no electro-mechanical brake for open/close stop required • Mounting orientation in any direction Position indicator High-visibility graduated dial • 4-20 mA or 500Ω optional feedback signal Conduit connections -

Publication 1346 October 1, 2010 Part 1 Page 263 ATTACHMENT 1

ATTACHMENT 1 ERROR REJECT CODE (ERC) DESCRIPTIONS 0001 o Page 1 of Form 1040, 1040A, 1040EZ, or 1040-SS (PR) must be present o The Summary Record must be present. 0002 o Form 1040 - When More than Four Dependents Box (SEQ 0209), equals “X”, Dependent First Name 1 (SEQ 0170) must equal “STMbnn”. 0003 o Tax Return Record Identification – The Tax Period of Form 1040/ 1040A/1040EZ/1040-SS (PR) (SEQ 0005) Page 1, must equal "201012" and | Tax Period of Form 1040/1040A (SEQ 0765) and of Form 1040-SS (PR) (SEQ 1605) Page 2, must also equal "201012". | 0004 o Tax Form - Primary SSN (SEQ 0010) must be within the valid ranges of SSN/ITIN's and cannot equal an ATIN. It must equal all numeric characters and cannot equal all blanks, zeros, ones, twos, threes, | fours, fives, sixes, sevens, eights or nines. Refer to Attachment 9 | for valid ranges of Social Security/Taxpayer Identification Numbers. o Primary SSN (SEQ 0010) is a required field. o Primary SSN (SEQ 0010) of the Tax Form must equal Taxpayer Identification Number (SEQ 0003) of Tax Return Record Identification Page 1. o Taxpayer Identification Number (SEQ 0003) of Tax Return Record Identification Page 1 must be significant. 0005 o Statement Record - The maximum number of Statement References within a tax return is 30. (A Statement Reference is defined as "STMbnn"; the value of "nn" refers to the Statement Number.) See Section 8 for Statement Record information. 0006 o Tax Form - Only the following characters are permitted in the Primary Name Control (SEQ 0050) and Spouse's Name Control (SEQ 0055): alpha, hyphen, and space. -

Datasheet Search Engine

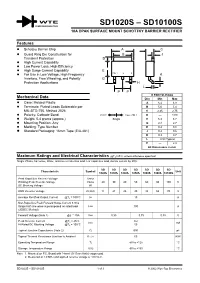

WTE SD1020S – SD10100S POWER SEMICONDUCTORS 10A DPAK SURFACE MOUNT SCHOTTKY BARRIER RECTIFIER Features ! Schottky Barrier Chip A C ! Guard Ring Die Construction for B J Transient Protection D ! High Current Capability ! Low Power Loss, High Efficiency ! High Surge Current Capability E ! For Use in Low Voltage, High Frequency PIN 1 2 3 K Inverters, Free Wheeling, and Polarity G Protection Applications H L P P D PAK/TO-252AA Mechanical Data Dim Min Max ! Case: Molded Plastic A 6.4 6.8 ! Terminals: Plated Leads Solderable per B 5.0 5.4 MIL-STD-750, Method 2026 C 2.35 2.75 ! Polarity: Cathode Band PIN 3 - + Case PIN 2 D —1.60 ! Weight: 0.4 grams (approx.) Single E 5.3 5.7 ! Mounting Position: Any G 2.3 2.7 ! Marking: Type Number H 0.4 0.8 ! Standard Packaging: 16mm Tape (EIA-481) J 0.4 0.6 K 0.3 0.7 L 0.50 Typical P —2.3 All Dimensions in mm Maximum Ratings and Electrical Characteristics @TA=25°C unless otherwise specified Single Phase, half wave, 60Hz, resistive or inductive load. For capacitive load, derate current by 20%. SD SD SD SD SD SD SD Characteristic Symbol Unit 1020S 1030S 1040S 1050S 1060S 1080S 10100S Peak Repetitive Reverse Voltage VRRM Working Peak Reverse Voltage VRWM 20 30 40 50 60 80 100 V DC Blocking Voltage VR RMS Reverse Voltage VR(RMS) 14 21 28 35 42 56 70 V Average Rectified Output Current @TL = 100°C IO 10 A Non-Repetitive Peak Forward Surge Current 8.3ms Single half sine-wave superimposed on rated load IFSM 100 A (JEDEC Method) Forward Voltage (Note 1) @IF = 10A VFM 0.55 0.75 0.85 V Peak Reverse Current @TA = 25°C 0.2 IRM mA At Rated DC Blocking Voltage @TA = 100°C 50 Typical Junction Capacitance (Note 2) Cj 600 pF Typical Thermal Resistance Junction to Ambient RJA 60 K/W Operating Temperature Range Tj -50 to +125 °C Storage Temperature Range TSTG -50 to +150 °C Note: 1. -

Rain-Praying in Eleventh-Century China Cong Ellen Zhang University of Virginia

Heaven, Spirits, and Political and Social Order: Rain-Praying in Eleventh-Century China Cong Ellen Zhang University of Virginia The centrality of agriculture in Chinese life ensured an interest in recording auspicious and abnormal climatic phenomena as well as natural disasters from the beginning of Chinese civilization. These records ranged from oracle bone and bronze inscriptions in the Shang (16th- mid-11th centuries BCE) and Zhou (1040s-256 BCE) periods to official documents and literati writing in the imperial times. Especially abundant in this body of literature was accounts of unseasonal and insufficient rainfall. A serious drought meant a poor harvest and famine for the local population. This was often followed by the disruption of social order in the forms of forced migration, banditry, and rebellions. This, along with the decreases in tax revenue and the demand for relief work, remained a major concern for the imperial state. Since the earliest times, Chinese cosmological ideas and political thought maintained that occurrences of natural disasters symbolized a breakdown of the balance and harmony between Heaven and man, often caused by irresponsible rulers and their representatives. One way to restore order and balance was through well-orchestrated ritual performances, during which the emperor or official-in-charge demonstrated his sincere concern for the suffering of the people and his utmost dedication to alleviate their miseries in exchange for the end of a disaster. Heaven and gods would then respond to the appeal, manifesting their power and benevolence while validating the legitimacy of the Son of Heaven and his rule. Rain-praying (祈雨, 禱雨, 求雨, 乞雨) ranked among the most enduring ritual traditions in Chinese history. -

2008 RI-2210.Qxp

RI-2210 UNDERPAYMENT OF ESTIMATED TAX BY INDIVIDUALS, ESTATES AND TRUSTS 2008 Name(s) shown on Form RI-1040, RI-1040NR, RI-1040S or RI-1041 Social Security Number/Federal IdentificationNumber PART 1 REQUIRED ANNUAL PAYMENT Enter your 2008 RI income tax from RI-1040, line 15 less lines 18D and 18E, RI-1040NR, line 15C less line 18E, RI-1040S, 1. 1. line 6 less line 10D or RI-1041, line 19C .......................................................................................................................................... 2. Enter 80% of the amount shown on line 1............................................................................................. 2. 3. RI taxes withheld for 2008 from RI-1040, line 18A, RI-1040NR, lines 18A, 18C and 18D, RI-1040S, line 10A or RI-1041, lines 3. 20A, 20C and 20D............................................................................................................................................................................. 4. Subtract line 3 from line 1 - (If the result is $250.00 or less, do not complete the rest of this form)................................................. 4. 5. Enter your 2007 RI tax from RI-1040, line 15 less lines 18D and 18E, RI-1040NR, line 15C less line 18E, RI-1040EZ, line 6 less 5. 10D or RI-1041, line19C ...................................................................................................................................................................... 6. Enter the SMALLER of line 2 or line 5.............................................................................................................................................. -

![[DO NOT PUBLISH] in the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the ELEVENTH CIRCUIT No. 19-13018 ___](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7764/do-not-publish-in-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-eleventh-circuit-no-19-13018-1667764.webp)

[DO NOT PUBLISH] in the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the ELEVENTH CIRCUIT No. 19-13018 ___

USCA11 Case: 19-13018 Date Filed: 08/23/2021 Page: 1 of 65 [DO NOT PUBLISH] IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT ________________________ No. 19-13018 ________________________ D.C. Docket No. 1:18-cr-20684-RNS-1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellee, versus TAMARA JEUNE, a.k.a. Tamara Voltaire, Defendant-Appellant. ________________________ No. 19-14890 ________________________ D.C. Docket No. 1:18-cr-20684-RNS-1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellee, versus TAMARA JEUNE, USCA11 Case: 19-13018 Date Filed: 08/23/2021 Page: 2 of 65 Defendant-Appellant. ________________________ Appeals from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida ________________________ (August 23, 2021) Before MARTIN, ROSENBAUM, and LUCK, Circuit Judges. PER CURIAM: A jury convicted Defendant-Appellant Tamara Jeune of one count of conspiracy to defraud the government, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 286, one count of filing false tax returns, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 287, and three counts of assisting and advising in the preparation of false tax returns, in violation of 26 U.S.C. § 7206(2). Jeune now appeals her convictions, the $398,021 in restitution to the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) that the district court ordered, and her sentence of 180 months of imprisonment. After careful review and with the benefit of oral argument, we conclude that the evidence supports Jeune’s convictions and calculated restitution amount, so we affirm in part. But we find clear error in the district court’s imposition of a two- point enhancement for obstruction of justice, so we vacate Jeune’s sentence and remand for resentencing. -

Series 1000 Electric Actuators Series 1000 Electric Actuators Design Features

SERIES 1000 ELECTRIC ACTUATORS SERIES 1000 ELECTRIC ACTUATORS DESIGN FEATURES Series 1000 On-Off Rotary Electric Actuator Basic Actuator: Torque Output Range: 347in-lb to 17,359in-lb Housing: NEMA 4X, watertight, corrosion-resistant, robust aluminum die cast Electric Motor: 10VAC, single phase, 60Hz totally enclosed, non-ventilated, high starting torque, reversible induction type, Class F insulation Thermal Overload Motor Protection: Auto reset thermal switch embedded in the motor winding - trips when the maximum winding temperature is exceded Position Limit Switches: x SPDT for Open and Close travel limit - easily adjustable, cam operated Position Indicator: Mechanical dome type with visiable red/yellow closed/open indicator Terminal Strip: Refer to wiring diagrams for details Conduit Entries: 1 x 1/” NPT for power and control wiring Power Gears: Alloy steel spur gears to final stage aluminum bronze worm sector gear Break: An electro-mechanical brake is NOT required. The worm gear drive prevents back driving and hunting Bearings: High quality alloy steel sleeve and ball bearings Manual Override: Handle Adjustable Mechanical Stops Ambient Temperature Range: -31°F to +150°F Certification and Approvals:CE, NEMA4, CSA, NRTL Internal Heater Optional Features • 0V AC/1/50-60Hz power • 1/4V DC 1005 through 100 • Torque Limit Switches for Close direction of travel • Feedback Potentiometer - 1000ohm • DeClutchable Handwheel Override SERIES 1000 ELECTRIC ACTUATORS ON-OFF SPECIFICATIONS Series 1000 On-Off Actuator Specifications Model 1005 1010 1020 1040 1060 1100 1150 1200 Output Torque(in-lb) 347 868 1736 347 508 8680 13,019 17,359 Output Torque(Nm) 39.3 98.06 196.13 39.7 588.4 980.66 1471 1961.3 Duty Cycle 75% 75% 50% 50% 50% 50% 50% 50% Travel Speed at 5 5 5 5 50 50 50 50 60Hz(Sec) Maximum Current .35/.18 .41/. -

DSX Modem Installation Manual

® DSX Modem Installation Manual DSX Access Systems, Inc. 10731 Rockwall Road Dallas, Texas 75238 888-419-8353 Sales, Shipping and Accounting 800-346-5288 Technical Support 214-553-6140 Phone www.dsxinc.com 214-553-6147 FAX Modem 02/05 DSX Access Systems, Inc. 10731 Rockwall Road Dallas, Texas 75238 888-419-8353 Sales, Shipping and Accounting 800-346-5288 Technical Support 214-553-6140 Phone www.dsxinc.com 214-553-6147 FAX Modem 02/05 Table of Contents Modem Operation Overview……………………………………………………………………………1 Modem recommendation…………………………………………………………………………….….2 Phone Call Description………………………………………………………………………………….2 Communication Security Password (Location Password)………………………………………………3 DSX Modem LED Operation.……………………………………………………………………….….4 Modem to PC Connections…………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Modem Power Sources………………………………………………………………………………….5 Modem Mounting in DSX Enclosures………………………………………………………………….5 Modem to DSX-1040, 1032, 1033 and 1034 Connections……………………………………………..7 Modem to DSX-1022, 1021 and 1020 via MCI………………………………………………………...8 Telephone Line Connections……………………………………………………………………………8 Initial Modem Communications Procedure for Dial-up Location………………………………………9 Modem Compatibility………………………………………………………………………………….11 Existing Modems …..………………………………………………………………………………….11 Modem Initialization Strings …..……………………………………………………………………...12 Changing the Modem Initialization String for the PC…………………………………………………13 Modem Speaker Volume…...………………………………………………………………………….13 Resetting the Modem…………………………………………………………………………………..13 Default Baud Rates…………………………………………………………………………………….13 -

Gilmore.Indictment

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY UNITED STATES OF AⅣ IERICA Criminal No.19- 18 UoS.C.§ 1014 V. 18 UoS.C.§ 2 26U.S.C.§ §7201,7202&7206(1) GEORGE GILNIIORE INDICTMENT The Grand Jury in and for the District of New Jersey, sitting in Trenton, charges: COUNT 1 (Evasion of the Pavment of Taxes Due and Owine - Calendar Years 2013. 2014. and 2015) 1. At all times relevant to Count 1 of this Indictment, unless otherwise indicated: a. Defendant GEORGE GILMORE ("defendant GILMORE") was an attomey and partner of a law firm, Gilmore & Monahan, P.A. (the "law firm"), located in Toms River, New Jersey. b. As one of two equity partners and shareholders of the law firm, defendant GILMORE owned fifty percent of the stock of the law firm, which operated as a "C Corporation." Under the Internal Revenue Code, the prohts of a C Corporation were taxed separately from its owners. c. Defendant GILMORE exercised primary control over the financial affairs of the law firm, which included, among other things, arranging the preparation and filing of the tax returns, paying taxes and creditors on behalf of the law firm, and determining his own compensation from the law firm. Defendant GILMORE also did not share full and complete information about the law firm's financial transactions with other attomeys at the law firm, including the other equity partner. d. The Intemal Revenue Service ("IRS") was an agency of the United States within the Department of Treasury, responsible for administering and enforcing the tax laws of the United States. -

Hi-8424-Manual.Pdf

Instruction Manual HI 8424NEW Portable pH/mV/°C Meter with Automatic Calibration and Battery Recharging System 1.800.561.8187 www. .com [email protected] Dear Customer, Thank you for choosing a HANNA instruments® product. Please read this instruction manual carefully before using the instrument. This manual will provide you with the necessary information for correct use of the instrument, as well as a precise idea of its versatility. If you need additional technical information, do not hesitate to e-mail us at [email protected] or see the back cover for our worldwide contact list. This instrument is in compliance with the directives. WARRANTYWARRANTYWARRANTY HI 8424NEW is guaranteed for two years against defects in workmanship and materials when used for its intended purpose and maintained according to instructions. Electrodes and probes are guaranteed for six months. This warranty is limited to repair or replacement free of charge. Damage due to accidents, misuse, tampering or lack of prescribed maintenance is not covered. If service is required, contact the dealer from whom you purchased the instru- ment. If under warranty, report the model number, date of purchase, serial number and the nature of the problem. If the repair is not covered by the warranty, you will be notified of the charges incurred. If the instruments are to be returned to Hanna Instruments, first obtain a Returned Goods Authorization number from the Technical Service department and then send it with shipping costs prepaid. When shipping any instrument, make sure