A Comparative Study of Schoolmasters in Eleventh-Century Normandy and the Southern Low Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 83, No. 150/Friday, August 3, 2018/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 83, No. 150 / Friday, August 3, 2018 / Notices 38161 Community Community map repository address Canadian County, Oklahoma and Incorporated Areas Project: 12–06–1030S Preliminary Date: February 8, 2018 City of El Reno ......................................................................................... Municipal Building, 101 North Choctaw Avenue, El Reno, OK 73036. Aransas County, Texas and Incorporated Areas Project: 15–06–0811S Preliminary Date: March 16, 2018 City of Aransas Pass ................................................................................ City Hall, 600 West Cleveland Boulevard, Aransas Pass, TX 78336. San Patricio County, Texas and Incorporated Areas Project: 15–06–0811S Preliminary Date: March 16, 2018 City of Aransas Pass ................................................................................ City Hall, 600 West Cleveland Boulevard, Aransas Pass, TX 78336. [FR Doc. 2018–16666 Filed 8–2–18; 8:45 am] 97.048, Disaster Housing Assistance to Brown Fund; 97.032, Crisis Counseling; BILLING CODE 9110–12–P Individuals and Households In Presidentially 97.033, Disaster Legal Services; 97.034, Declared Disaster Areas; 97.049, Disaster Unemployment Assistance (DUA); Presidentially Declared Disaster Assistance— 97.046, Fire Management Assistance Grant; DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND Disaster Housing Operations for Individuals 97.048, Disaster Housing Assistance to and Households; 97.050, Presidentially Individuals and Households In Presidentially SECURITY Declared Disaster Assistance to Individuals -

The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions

Scholars Crossing History of Global Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions" (2009). History of Global Missions. 3. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of Global Missions by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Middle Ages 500-1000 1 3 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions AD 500—1000 Introduction With the endorsement of the Emperor and obligatory church membership for all Roman citizens across the empire, Roman Christianity continued to change the nature of the Church, in stead of visa versa. The humble beginnings were soon forgotten in the luxurious halls and civil power of the highest courts and assemblies of the known world. Who needs spiritual power when you can have civil power? The transition from being the persecuted to the persecutor, from the powerless to the powerful with Imperial and divine authority brought with it the inevitable seeds of corruption. Some say that Christianity won the known world in the first five centuries, but a closer look may reveal that the world had won Christianity as well, and that, in much less time. The year 476 usually marks the end of the Christian Roman Empire in the West. -

Ofgphigh Schoof

---=-----;~.~- - - - . -.' • PW;=. _. P -." ! < , $, >. ~ $C m / All the News Home of the News of All the Pointes • Every Thursday Morning * * * ros.s.e Call TUxedo 2-6900 Complet~ News Coverage of AlI'the.. Pointes Entered as Sc;:ond Class Matter 5e Per Copy VOLUME 19-No. 7 at the Post Office ,at Detro~t. Mich. GROSSi: rOINTE, MICHI'GAN, FE~RUARY 13, 1958 , 13.50 Per Yea2 24 PAGES Fully Paid Circulation ----------~,;--------------...,-------------~-~------:-------------~..:-_---:_...:-_----------'----------------_._--_.) HEADLIl\' ES Women Prep'are for World Day of Pray'er Pick Jerry Gerich Gro~pFights of the . - ••. IChalh Store \VEEK As Compiled by the For New PrInCIpal IProposals Grosse Pointe News Poi n t e Business Men's Association Opposing, Thursday, February 6 Of GPHigh Schoof THE- SECOND SPECTACU- Sales on Sabbath LAR failure of a Navy satel- '--- I lite-bearing Vanguard t est Canadian-Born Graduate of Northwestern University The Grosse Pointe Busi- missile was explained officia'l- Being Brought Here from Similar Post in Arlington, Va. ness Men's Association has ly late Wednesday as due to --------- gone on record as opposed d e f e c t s in the first-stage Jerry J. G;erich of Arlington, Virginia, has been ap- to Sunday business, putting engine cont:ol s y s t em. The pointed Principal of the Grosse Pomte High School, the s p e cia 1 emphasis on the flaws, after .three seconds, Board of Education of the Grosse Pointe Public School sale of merchandise by split the rocket in two and caused its ultimate destruction System announced February 5. -

CHAPTER THIRTY the AFFLUENT SOCIETY Objectives a Thorough Study of Chapter 30 Should Enable the Student to Understand: 1

CHAPTER THIRTY THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY Objectives A thorough study of Chapter 30 should enable the student to understand: 1. The strengths and weaknesses of the economy in the 1950s and early 1960s. 2. The changes in the American lifestyle in the 1 950s. 3. The significance of the Supreme Court’s desegregation decision and the early civil rights movement. 4. The characteristics of Dwight Eisenhower’s middle-of-the-road domestic policy. 5. The new elements of American foreign policy introduced by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. 6. The causes and results of increasing United States involvement in the Middle East. 7. The sources of difficulties for the United States in Latin America. 8. The reasons for new tensions with the Soviet Union toward the end of the Eisenhower administration. Main Themes 1. That the technological, consumer-oriented society of the 1 950s was remarkably affluent and unified despite the persistence of a less privileged underclass and the existence of a small corps of detractors. 2. How the Supreme Court’s social desegregation decision of 1954 marked the beginning of a civil- rights revolution for American blacks. 3. How President Dwight Eisenhower presided over a business-oriented “dynamic conservatism” that resisted most new reforms without significantly rolling back the activist government programs born in the 1930s. 4. That while Eisenhower continued to allow containment by building alliances, supporting anticommunist regimes, maintaining the arms race, and conducting limited interventions, he also showed an awareness of American limitations and resisted temptations for greater commitments. Glossary 1. Third World A convenient way to refer to all the nations of the world besides the United States, Canada, the Soviet Union, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, China, and the countries of Europe. -

Social Change in Eleventh-Century Armenia: the Evidence from Tarōn Tim Greenwood (University of St Andrews)

Social Change in Eleventh-Century Armenia: the evidence from Tarōn Tim Greenwood (University of St Andrews) The social history of tenth and eleventh-century Armenia has attracted little in the way of sustained research or scholarly analysis. Quite why this should be so is impossible to answer with any degree of confidence, for as shall be demonstrated below, it is not for want of contemporary sources. It may perhaps be linked to the formative phase of modern Armenian historical scholarship, in the second half of the nineteenth century, and its dominant mode of romantic nationalism. The accounts of political capitulation by Armenian kings and princes and consequent annexation of their territories by a resurgent Byzantium sat very uncomfortably with the prevailing political aspirations of the time which were validated through an imagined Armenian past centred on an independent Armenian polity and a united Armenian Church under the leadership of the Catholicos. Finding members of the Armenian elite voluntarily giving up their ancestral domains in exchange for status and territories in Byzantium did not advance the campaign for Armenian self-determination. It is also possible that the descriptions of widespread devastation suffered across many districts and regions of central and western Armenia at the hands of Seljuk forces in the eleventh century became simply too raw, too close to the lived experience and collective trauma of Armenians in these same districts at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, to warrant -

Item Description 2021 List Omnia Discount Omnia Price 7200

Play & Park Structures 2021 Omnia Price List Effective: 1/4/2021 * Play Equipment Installation 35% of 2021 Retail Price. Minimum Retail Price $5000.00 to provide Installation. * Prevailing Wage Installation 100% of 2021 Retail Price. Minimum Retail Price $5000.00 to provide Installation. * Custom Playground Designs 30% off Retail Price. * Escalator of 50% of our MSRP for Prevailing wage installation in these 5 CA counties for a total of 150% of MRSP (San Diego, Imperial, Riverside, San Bernardino & Orange Co) Item Description 2021 List Omnia Discount Omnia Price 7200 ANSWER WHEEL ASSEMBLY $ 263.00 30% $ 184.10 7201 MAZE ASSEMBLY $ 176.00 30% $ 123.20 7202 ECHO CHAMBER ASSEMBLY $ 114.00 30% $ 79.80 7203 FLAT MIRROR ASSEMBLY $ 88.00 30% $ 61.60 7204 STAINED GLASS ASSY-RED $ 107.00 30% $ 74.90 7205 STAINED GLASS ASSY-YELLOW $ 110.00 30% $ 77.00 7206 HYPNO WHEEL ASSY $ 152.00 30% $ 106.40 7300 MAGNET PANEL $ 234.00 30% $ 163.80 7301 MIRROR PANEL $ 385.00 30% $ 269.50 7302 LACING PANEL $ 302.00 30% $ 211.40 7304 WINDOW PANEL $ 356.00 30% $ 249.20 7305 PAINT PANEL $ 489.00 30% $ 342.30 7306 THEATRE PANEL $ 563.00 30% $ 394.10 7309 2-SIDED SPIN CHIMES $ 1,445.00 30% $ 1,011.50 7310 20"HYPNETIC WHEEL 2-SIDE $ 1,187.00 30% $ 830.90 7311 20"HYPNETIC WHEEL 1-SIDE $ 1,865.00 30% $ 1,305.50 7312 12"HYPNETIC WHEEL 2-SIDE $ 1,291.00 30% $ 903.70 7313 1-SIDED 20"BELL $ 855.00 30% $ 598.50 7314 1-SIDED 12"BELL $ 514.00 30% $ 359.80 7315 2-SIDED 20"BELL $ 1,332.00 30% $ 932.40 7316 2-SIDED 12"BELL $ 783.00 30% $ 548.10 7317 20" 1-SIDED WINDOW-GREEN $ 363.00 -

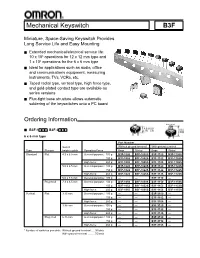

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F Miniature, Space-Saving Keyswitch Provides Long Service Life and Easy Mounting ■ Extended mechanical/electrical service life: 10 x 106 operations for 12 x 12 mm type and 1 x 106 operations for the 6 x 6 mm type ■ Ideal for applications such as audio, office and communications equipment, measuring instruments, TVs, VCRs, etc. ■ Taped radial type, vertical type, high force type, and gold-plated contact type are available as series versions ■ Flux-tight base structure allows automatic soldering of the keyswitches onto a PC board Ordering Information Flat Projected ■ B3F-1■■■, B3F-3■■■ 6 x 6 mm type Part Number Switch Without ground terminal With ground terminal Type Plunger height x pitch Operating Force Bags Sticks* Bags Sticks* Standard Flat 4.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1000 B3F-1000S B3F-1100 B3F-1100S 150 g B3F-1002 B3F-1002S B3F-1102 B3F-1102S High-force: 260 g B3F-1005 B3F-1005S B3F-1105 B3F-1105S 5.0 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1020 B3F-1020S B3F-1120 B3F-1120S 150 g B3F-1022 B3F-1022S B3F-1122 B3F-1122S High-force: 260 g B3F-1025 B3F-1025S B3F-1125 B3F-1125S 5.0 x 7.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-1110 — Projected 7.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1050 B3F-1050S B3F-1150 B3F-1150S 150 g B3F-1052 B3F-1052S B3F-1152 B3F-1152S High-force: 260 g B3F-1055 B3F-1055S B3F-1155 B3F-1155S Vertical Flat 3.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3100 — 150 g — — B3F-3102 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3105 — 3.85 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3120 — 150 g — — B3F-3122 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3125 — Projected 6.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3150 — 150 g — — B3F-3152 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3155 — * Number of switches per stick: Without ground terminal ... -

Personal Names and Denomination of Livonians in Early Written Sources

ESUKA – JEFUL 2014, 5–1: 13–26 PERSONAL NAMES AND DENOMINATION OF LIVONIANS IN EARLY WRITTEN SOURCES Enn Ernits Estonian University of Life Sciences Abstract. This paper presents the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; specifies their chronology; and analyses the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. If we consider the dating of the event, the earliest sources mentioning Livonians are Gesta Danorum and the Tale of Bygone Years (both 10th century), but both sources present rather dubious information: in the first the battle of Bråvalla itself or the date are dubious (6th, 8th or 10th century); in the latter we cannot be sure that the member of the Rus delegation was really a Livonian. If we consider the time of recording, the earliest sources are two rune inscriptions from Sweden (11th century), and the next is the list of neighbouring peoples of the Russians from the Tale of Bygone Years (12th century). The personal names Bicco and Ger referred in Gesta Danorum, and Либи Аръфастовъ in Tale of Bygone Years are very problematic. The first certain personal name of a Livonian is *Mustakka, *Mustukka or *Mustoikka (from Finnic *musta ‘black’) written in 1040–1050s on a strip of birch bark in Novgorod. Keywords: Livs, Finnic peoples, ethnonyms, anthroponyms, onomastics DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2014.5.1.01 1. Introduction This paper (1) seeks to present the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; (2) to specify their chronology; (3) and to analyse the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. It is supple- mental to the paper by Mauno Koski on words denoting Livonians (Koski 2011). -

Vehicle List and Driver Assignments

Effingham County Board of Education Vehicle List 6/30/2013 Vehicle List and Driver Assignments Insurance Veh# Make Year Model Cost Assigned Driver/Location Tag # Vin # Car# Book Value 940 L0163292 1994 94 INT 39,994.15 Spare BB 66 15915 1HVBBACNXSH623821 151 - 941 L016393 1994 94 INT 39,994.15 Spare BB 66 15916 1HVBBACN1SH623822 153 - 942 L016394 1994 94 INT 39,994.15 BB 66 15917 1HVBBACN3SH623823 152 - 944 L016396 1994 94 INT 39,994.15 Spare BB 66 15918 1HVBBACN7SH623825 155 - 945 L016397 1994 94 INT 39,994.15 Spare BB 66 15919 1HVBBACN9SH623826 156 - 946 L016398 1994 94 INT 39,994.15 Spare BB 66 15920 1HVBBACNOSH623827 158 - 947 L016399 1994 94 INT 39,994.15 Spare BB 66 15921 1HVBBACN2SH623828 157 - 951 L020327 1995 95 FORD 41,995.62 BB 66 15923 1FDXB80C1SVA75535 165 - 952 L020328 1995 95 FORD 41,995.62 Spare BB 66 15924 1FDXB80C3SVA75536 164 - 953 L020329 1995 95 FORD 41,995.62 Spare BB 66 15925 1FDXB80C5SVA75537 168 - 954 L020330 1995 95 FORD 41,995.62 Spare BB 66 15926 1FDXB80CXSVA79843 169 - 956 L020332 1995 95 FORD 41,995.62 Spare BB 66 15928 1FDXB80C8SVA76228 166 - 962 L024118 1996 96 FORD 41,995.62 Spare BB 66 15963 1FDXB80C5VVA03628 176 - 963 L024119 1996 96 FORD 41,995.62 Spare BB 66 15964 1FDXB80C7VVA03629 175 - 964 L024117 1996 96 FORD 41,995.62 Spare BB 54 15965 1FDXB80C3VVA03627 177 - 965 L024116 1996 96 FORD 41,995.62 Spare BB 54 15966 1FDXB80C1VVA03626 178 - 970 L028102 1997 97 INT 44,597.30 Spare BB 66 16029 1HVBBABN8VH496962 181 - 971 L028103 1997 97 INT 44,597.30 Spare BB 66 16048 1HVBBABNXVH496963 182 - 973 L028105 -

UC Berkeley Berkeley Planning Journal

UC Berkeley Berkeley Planning Journal Title Economic Development and Housing Policy in Cuba Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p00546t Journal Berkeley Planning Journal, 2(1) ISSN 1047-5192 Author Fields, Gary Publication Date 1985 DOI 10.5070/BP32113199 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING POLICY IN CUBA Gary Fields Introduction Since the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Cuba's economic development has been marked by efforts to achieve fo ur basic objectives: I) agrarian reform, including land redistribution, creation of state and cooperative farms, and agricultural crop diversification; 2) economic growth and industrial development, including the siting of new industries and employment opportunities in the countryside; 3) wealth and income redistribution from rich to poor citizens and from urban to rural areas; 4) provision of social services in all areas of the country, including nationwide literacy, access to medical care in the rural areas, and the creation of adequate and affordable housing nationwide. It is important to note that all of these objectives contain an emphasis on rural development. This emphasis was the result of decisions by Cuban economic planners to correct what had been perceived as the most serious ·negative consequence of the Island's economic past--the economic imbalance between town and coun try. 1 The dependence of the Cuban economy on sugar production, with its dramatic seasonal employment shifts, the control of the Island's sugar industry by American companies and the siphoning of sugar profits out of Cuba, the concentration in Havana of the wealth created primarily in the countryside, and the lack of economic opportunities and social services in the rural areas, were the main features of an economic and social system that had impoverished the rural population, creating a movement for change. -

Herefore, Incentives Typically Offered and Used for Development Would Be Replaced with the EB-5 Investment

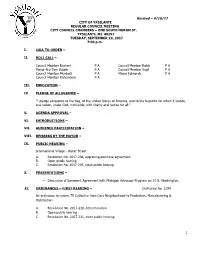

Revised – 9/18/17 CITY OF YPSILANTI REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS – ONE SOUTH HURON ST. YPSILANTI, MI 48197 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2017 7:00 p.m. I. CALL TO ORDER – II. ROLL CALL – Council Member Bashert P A Council Member Robb P A Mayor Pro-Tem Brown P A Council Member Vogt P A Council Member Murdock P A Mayor Edmonds P A Council Member Richardson P A III. INVOCATION – IV. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE – “I pledge allegiance to the flag, of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” V. AGENDA APPROVAL – VI. INTRODUCTIONS – VII. AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION – VIII. REMARKS BY THE MAYOR – IX. PUBLIC HEARING – International Village - Water Street A. Resolution No. 2017-208, approving purchase agreement. B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-209, close public hearing X. PRESENTATIONS – Discussion of Easement Agreement with Michigan Advocacy Program on 15 N. Washington. XI. ORDINANCES – FIRST READING – Ordinance No. 1294 An ordinance to rezone 75 Catherine from Core Neighborhood to Production, Manufacturing & Distribution. A. Resolution No. 2017-210, determination B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-211, close public hearing 1 XII. CONSENT AGENDA – Resolution No. 2017-212 1. Resolution No. 2017–213, approving minutes of August 22 and September 5, 2017. 2. Resolution No. 2017-214, approving the issuance of a blanket permit for window signs of any size for the month of October for businesses that participate with the Eastern Michigan University’s “Follow the Green & White Road” homecoming spirit project. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Modeling

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Modeling, Characterization and Simulation of On-Chip Power Delivery Networks and Temperature Profile on Multi-Core Microprocessors A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering by Duo Li December 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sheldon X.-D. Tan, Chairperson Dr. Yingbo Hua Dr. Frank Vahid Copyright by Duo Li 2010 The Dissertation of Duo Li is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGMENT There are many thanks to many people who made this dissertation possible. First of all, I would like to thank my Ph.D. advisor Dr. Sheldon Tan for the continuous support to my Ph.D. study and research work. Thank him for guiding me on my research road and providing me the great lab research environment. I could not have finished my dissertation successfully without his encouragement, sound advice, good teaching and lots of good ideas. Besides my advisor, I would like to thank the rest of my Ph.D. dissertation committee members Dr. Yingbo Hua and Dr. Frank Vahid, for their encouragement, comments and questions. I would like to thank all my labmates for their support and encouragement. I could not have had the better understanding on my research without the frequent discussions with them. I would like to thank my parents Daping Li and Yuqin Cong for giving birth to me, rasing me, teaching me, supporting me and loving me all the time. Last but not the least, I would like to thank my lovely wife Shan Shan. Thanks for being with me together during my Ph.D.