UC Berkeley Berkeley Planning Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon Dale T

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska- Extension Lincoln Extension 2006 EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon Dale T. Lindgren University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Lindgren, Dale T., "EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon" (2006). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. 4802. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/4802 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. - CYT vert . File NeBrasKa s Lincoln EXTENSION 85 EC1255 E 'Z oro n~ 1255 ('r'lnV 1 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon (2006) Cooperative Extension Service Extension .circular Received on: 01- 24-07 University of Nebraska, Lincoln - - Libraries Dale T. Lindgren University of Nebraska-Lincoln 00IANR This is a joint publication of the American Penstemon Society and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. We are grateful to the American Penstemon Society for providing the funding for the printing of this publication. ~)The Board of Regents oft he Univcrsit y of Nebraska. All rights reserved. Table -

CHAPTER THIRTY the AFFLUENT SOCIETY Objectives a Thorough Study of Chapter 30 Should Enable the Student to Understand: 1

CHAPTER THIRTY THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY Objectives A thorough study of Chapter 30 should enable the student to understand: 1. The strengths and weaknesses of the economy in the 1950s and early 1960s. 2. The changes in the American lifestyle in the 1 950s. 3. The significance of the Supreme Court’s desegregation decision and the early civil rights movement. 4. The characteristics of Dwight Eisenhower’s middle-of-the-road domestic policy. 5. The new elements of American foreign policy introduced by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. 6. The causes and results of increasing United States involvement in the Middle East. 7. The sources of difficulties for the United States in Latin America. 8. The reasons for new tensions with the Soviet Union toward the end of the Eisenhower administration. Main Themes 1. That the technological, consumer-oriented society of the 1 950s was remarkably affluent and unified despite the persistence of a less privileged underclass and the existence of a small corps of detractors. 2. How the Supreme Court’s social desegregation decision of 1954 marked the beginning of a civil- rights revolution for American blacks. 3. How President Dwight Eisenhower presided over a business-oriented “dynamic conservatism” that resisted most new reforms without significantly rolling back the activist government programs born in the 1930s. 4. That while Eisenhower continued to allow containment by building alliances, supporting anticommunist regimes, maintaining the arms race, and conducting limited interventions, he also showed an awareness of American limitations and resisted temptations for greater commitments. Glossary 1. Third World A convenient way to refer to all the nations of the world besides the United States, Canada, the Soviet Union, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, China, and the countries of Europe. -

Box Pack Price Guide Effective October 1, 2006 Table of Contents

Introducing Architecturally Inspired Collections Box Pack Price Guide effective October 1, 2006 Table of Contents KWIKSET ULTRAMAX SIGNATURES Metal INTERCONNECT Handlesets Metal Interconnect...................................................................... 26 Ashfield, Avalon, Amherst, Arlington, Chelsea, Hawthorne, Shelburne, Sheridan, Wellington .................... 2-6 RESIDENTIAL/LIGHT COMMERCIAL Baldwin Handlesets with K-Keyway ...................................... 7 Kingston ................................................................................ 27 Knobs Abbey, Circa, Hancock, Laurel ................................................ 8 LATCHES, STRIKES & CYLINDERS Deadlatch Plain Latches, 6-Way Latches .............................. 28-29 Levers 580, 780, 970, 980S, 660 Series Deadbolt Latches ............... 30-31 Brooklane, Commonwealth, Pembroke .................................. 9 Strikes & Boxes ...................................................................... 32-34 Deadbolts Cylinders................................................................................. 35-37 980S Series, 780 Series ....................................................... 10 KEYING KWIKSET MAXIMUM SECURITY Keys & Key Blanks ...................................................................... 38 Handlesets Keying Charges and Supplies ............................................... 38-40 Gibson ................................................................................... 12 Sonoma ............................................................................... -

Mercury/Turbo Program

Door Security Solutions Canada MERCURY/TURBO PROGRAM The global leader in door opening solutions Mercury Program 1.800.461.3007 Terms & Conditions www.assaabloy.ca TERMS & CONDITIONS DSS Canada, a division of ASSA ABLOY of Canada Ltd. and all of its current and future associated companies, subsidiaries and operating brands (hence forth referred to as ASSA ABLOY DSS Canada) reserve the right to decline an order, in whole or in part, when the type or quantity of goods or credit worthiness of the Purchaser is not satisfactory to us in our sole and absolute discretion. The terms and conditions contained herein constitute the entire agreement between the parties. Purchase Orders, Quotations (“Quote”) requests, Acknowledgements or the like issued by the Purchaser that have contrary standard terms and conditions are not binding on ASSA ABLOY DSS Canada , unless such terms and conditions are approved in a separate written agreement by ASSA ABLOY DSS Canada ’s authorized representatives. In the event of an acceptance of Purchaser’s Purchase Order by ASSA ABLOY DSS Canada, the Purchaser agrees that such acceptance is solely conditioned on Purchaser’s acceptance of the terms and conditions set forth in this instrument, regardless of the terms and conditions specified in the Purchaser’s Purchase order. The terms and conditions in Purchaser’s Purchase Order which conflict with terms and conditions of this instrument shall be disregarded and are hereby rejected, and this instrument shall constitute the entire agreement between ASSA ABLOY DSS Canada and the Purchaser. In the event that ASSA ABLOY DSS Canada does not enforce or require strict performance of any term or condition hereof, or of any other document, instrument or other agreement relating to goods sold, such lack of enforcement or requirement of strict performance will not waive, affect or diminish any right of ASSA ABLOY DSS Canada to enforce or require strict performance of such term or condition in the future. -

Innovator, 1981-04-14 Student Services

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Innovator Student Newspapers 4-14-1981 Innovator, 1981-04-14 Student Services Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/innovator Recommended Citation Governors State University Student Services, Innovator (1981, April 14). http://opus.govst.edu/innovator/186 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Innovator by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY INNOVATOR CHIVES Volume 7 Number 18 April 14, 1981 VETS URGE ''STOP THE CUTS'' by Jeff Leanna Along with the massive defaults due to the ten year delimiting date befal ling Many GSU student veterans now the Viet Nam era vets, an additional getting financial assistance to pursue factor may hurt veteran enrollment: the their education may find themselves VEAP system, which replaced the Gl without funds this year. And a great Bill as of January 1st, 1977. many more will lose out in fiscal '82. The VEAP, or Veterans Educat ional This in turn, may affect total veteran Assistance Program, is an educat ional enrollment here. benefits system allowing the ser GSU is not the only school to be vicemen to make contributions of up to experiencing this problem . The $2700 of their own pay toward an in nat ional total of vet enrollment may dividual educat ional fund. The service soon drop off sharply as a result of then matches the amount on a two-for factors independent of all the other one basis, thus giving the vet a total of current economic woes. -

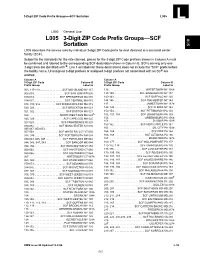

DMM L005 3-Digit ZIP Code Prefix Groups--SCF Sortation

3-Digit ZIP Code Prefix Groups—SCF Sortation L005 L L000 General Use L005 3-Digit ZIP Code Prefix Groups—SCF 005 Sortation L005 describes the service area by individual 3-digit ZIP Code prefix for mail destined to a sectional center facility (SCF). Subject to the standards for the rate claimed, pieces for the 3-digit ZIP Code prefixes shown in Column A must be combined and labeled to the corresponding SCF destination shown in Column B. SCFs serving only one 3-digit area are identified with S; Line 1 on labels for these destinations does not include the “SCF” prefix before the facility name. Unassigned 3-digit prefixes or assigned 3-digit prefixes not associated with an SCF are omitted. Column A Column A 3-Digit ZIP Code Column B 3-Digit ZIP Code Column B Prefix Group Label to Prefix Group Label to 005, 117-119. .SCF MID-ISLAND NY 117 136 . WATERTOWN NY 136S 006-009. SCF SAN JUAN PR 006 137-139. SCF BINGHAMTON NY 137 010-013. SCF SPRINGFIELD MA 010 140-143. .SCF BUFFALO NY 140 014-017. SCF CENTRAL MA 015 144-146. .SCF ROCHESTER NY 144 018, 019, 055 . SCF MIDDLESEX-ESX MA 018 147 . .JAMESTOWN NY 147S 020, 023 . .SCF BROCKTON MA 023 148, 149 . SCF ELMIRA NY 148 021, 022 . SCF BOSTON MA 021 150-154. SCF PITTSBURGH PA 150 024 . NORTHWEST BOS MA 024S 155, 157, 159 . SCF JOHNSTOWN PA 159 025, 026 . SCF CAPE COD MA 025 156 . GREENSBURG PA 156S 158 . DU BOIS PA 158S 027-029. -

Download This Article in PDF Format

A&A 500, 1327–1336 (2009) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200911802 & c ESO 2009 Astrophysics Observations of 44 extragalactic radio sources with the VLBA at 92 cm A list of potential calibrators and targets for LOFAR and RadioAstron H. Rampadarath1,2, M. A. Garrett3,2,4, and A. Polatidis1,3 1 Joint Institute for VLBI in Europe (JIVE), Postbus 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands e-mail: [rampadarath;polatidis]@astron.nl 2 Sterrewacht Leiden, Leiden University, Oort Building, Neils Bhorweg 2, 2333 CA, Leiden, The Netherlands 3 Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON), Postbus 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 4 Centre for Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Mail number H39, PO Box 218, Hawthorn, Victoria 3122, Australia Received 5 February 2009 / Accepted 14 March 2009 ABSTRACT Aims. We have analysed VLBA 92 cm archive data of 44 extragalactic sources in order to identify early targets and potential calibrator sources for the LOFAR radio telescope and the RadioAstron space VLBI mission. Some of these sources will also be suitable as “in- beam” calibrators, permitting deep, wide-field studies of other faint sources in the same field of view. Methods. All publicly available VLBA 92 cm data observed between 1 January 2003 to December 31, 2006 have been analysed via an automatic pipeline, implemented within AIPS. The vast majority of the data are unpublished. Results. The sample consists of 44 sources, 34 of which have been detected on at least one VLBA baseline. 30 sources have sufficient data to be successfully imaged. Most of the sources are compact, with a few showing extended structures. -

Tree-Ring Analysis of the Anglo-Scandinavian Oak Timbers by Cathy Tyers and Jennifer Hillam

The Archaeology of York Anglo-Scandinavian York 8/5 Anglo-Scandinavian Occupation at 16–22 Coppergate: Defining a Townscape Appendix 3: Tree-Ring Analysis of the Anglo-Scandinavian Oak Timbers by Cathy Tyers and Jennifer Hillam i List of Figures Fig.1 Bar diagram showing the relative positions of the dated ring sequences from Periods 2-5 and their associated felling dates. ................................................................................................................................ 4–6 Fig.2 Summary of the interpreted felling dates or date ranges ............................................................................................. 7 Fig. 3 Histogram showing the distribution of the sapwood values for the 13 measured samples with bark edge and the 2 sigma range of logarithmic values for the sapwood range ........................................... 15 Fig. 4 Histogram showing the distribution of the pseudo-sapwood values derived by assuming simultaneous felling of timbers with sapwood within structures with at least one timber with bark edge and the 2 sigma range of logarithmic values for the sapwood range .................................................... 15 Fig. 5a Diagram comparing the ring sequence length and average growth rates (average ring widths) of all of the dated timbers ............................................................................................................................................... 17 Fig.5b Diagram comparing the ring sequence length and average growth rates (average -

Tourism, the Economy, Population Growth, and Conservation in Galapagos

Tourism, the Economy, Population Growth, and Conservation in Galapagos Bruce Epler CHARLES DARWIN FOUNDATION Puerto Ayora, Santa Cruz Island, Galapagos Islands, Ecuador Revised and Updated in September 2007 Tourism, the Economy, Population Growth, and Conservation in Galapagos ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is particularly indebted to Susana Cardenas who, in addition to providing general guidance and logistical support, oversaw the distribution and collection of surveys and data entry. Johanna Castañeda assisted in distributing surveys to tourists waiting to depart the airport on Baltra and data entry. Liz Llerena assisted in data entry and interviews with hotel owners on Santa Cruz. Jairo Alvarado circulated surveys in the airport on San Cristóbal. Paulina Buenaño, Carmen Nicolade, and Delsy Jaramillo assisted with surveys and interviews with hotels on Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal, and Isabela. Graham Watkins, Executive Director of the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF), oversaw the study, provided numerous and relevant data files and studies, and submitted comments that improved the study. Johannah Barry, President of the Galapagos Conservancy, contributed data and insight into tourists’ and industry donations. Roslyn Cameron shared her knowledge about tour vessels, tourists, and fundraising. Craig MacFarland added information on the early years of the CDF, the development of the tourism industry, and ongoing and evolving issues and concerns. Oscar Aguirre, of the Galapagos Chamber of Tourism (CAPTURGAL), generously supplied summaries of survey information collected over several years. Edwin Naula, Head of the Galapagos National Park Service’s Tourism Unit, and Daniel Silva provided useful data compiled by the Park Service. Eliecer Cruz, of the World Wildlife Fund, provided insight into immigration, industry trends, and changes occurring in populated areas. -

Smallpox in Countries Non-Endemic

CHAPTER 23 SMALLPOX IN NON-ENDEMIC COUNTRIES Contents Page Introduction 1069 Criteria for defining non-endemic countries 1070 The significance of smallpox in non-endemic countries 1071 Actions taken by the non-endemic countries 1071 Actions taken by WHO 1073 Smallpox in Europe, 1959-1978 1073 Sources of importations 1073 Nature of index cases 1075 Delays in notification 1076 Transmission from imported cases 1076 Case studies of importations into Europe 1078 Importations into North America after 1959 1081 Importations into Japan 1081 Importations into recently endemic countries, 1959-1976 1082 Africa 1083 South America 1085 Southern Asia 1085 The 1970-1 972 outbreak in south-western Asia and Europe 1087 Iran 1088 Iraq 1090 Syrian Arab Republic 1090 Yugoslavia 1091 Laboratory-associated outbreaks in the United Kingdom 1095 The London outbreak, 1973 1095 The Birmingham outbreak, 1978 1097 Outbreak of variola minor in the Midlands and Wales, 1966 1098 Conclusions 1100 INTRODUCTION world in the 1960s and early 1970s, cases continued to be imported into smallpox-free In the preceding 11 chapters we have countries. The annual numbers of smallpox systematically reviewed the elimination of cases in most of the larger countries between smallpox from the 31 countries in which it 1920 and 1958 are tabulated in Chapter 8. The was endemic in 1967 and 2 other countries year in which smallpox was last endemic in (Botswana and the Sudan) in which endem- each of these countries is indicated in the icity was re-established after 1967. Because tables; cases occurring after that year were smallpox was endemic in many parts of the due to importations. -

The Role of Fiscal and Structural Po Li Cies in German Unification

XII The Role of Fiscal and Structural Policies in German Unification Lessons from the Past Thomas Mayer The process of Gennan economic, monetary , and of economic policy was, therefore, to provide a secure social union (GEMSU) raises many questions about the and unobtrusive legal and financial framework within role for economic policy, both in influencing the overall which markets could operate efficiently. degree of resource use in the economy and in pursuing Ordnungspolitik, as this policy has been called, allo an efficientallocation of resources. This chapter analyzes cated clearly defined tasks to each aspect of economic these questions against the background of past experience policy, that is, monetary, fiscal, and structural policy. with economic policy in the Federal Republic of Germany The main task of monetary policy was to ensure stability (FRG). Three major periods of economic policymaking of prices and the currency. This required the establishment can be distinguished in the FRG: fTom 1948 until about of a strong and independent central bank that was legally the mid-1960s, a period of strongly market-oriented bound to pursue these objectives. Thus, the central bank's policies associated with Ludwig Erhard; from the mid- commitment to these objectives could not be overruled 1960s to perhaps the early 1980s, a period of Keynesian by the government. Fiscal policy was charged with the policies associated with Karl Schiller; and, since the role of providing a tax system that generated enough early 1980s, a revival of Erhardian ideas.' revenue (with as little distortion of market signals as possible) to finance expenditures for the classical tasks of government. -

Biographies MA.B1-Ttlpgs

MA.b1-ttlpgs. qxp 4/19/04 1:53 PM Page 1 Biographies MA.b1-ttlpgs. qxp 4/19/04 1:53 PM Page 3 Biographies Volume 1: A-I JUDSON KNIGHT Edited by Judy Galens Judson Knight Judy Galens, Editor Staff Diane Sawinski, U•X•L Senior Editor Carol DeKane Nagel, U•X•L Managing Editor Thomas L. Romig, U•X•L Publisher Margaret Chamberlain, Permissions Associate (Pictures) Maria Franklin, Permissions Manager Randy Bassett, Imaging Database Supervisor Daniel Newell, Imaging Specialist Pamela A. Reed, Image Coordinator Robyn V. Young, Senior Image Editor Rita Wimberley, Senior Buyer Evi Seoud, Assistant Production Manager Dorothy Maki, Manufacturing Manager Pamela A. E. Galbreath, Senior Art Director Kenn Zorn, Product Design Manager Marco Di Vita, the Graphix Group, Typesetting Middle Ages: Biographies Cover photograph of T’ai Tsung reproduced by permission of the Granger Collection, New York. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Knight, Judson. Middle ages. Biographies / Judson Knight ; Judy Galens, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7876-4857-4 (set) — ISBN 0-7876-4858-2 (vol. 1) — ISBN 0-7876-4859-0 (vol. 2 : hardcover) 1. Biography—Middle Ages, 500-1500. 2. Civilization, Medieval. 3. World history. I. Galens, Judy, 1968- II. Title. CT114 .K65 2000 920’.009’02—dc21 00–064864 This publication is a creative work fully protected by all applicable copyright laws, as well as by misappropriation, trade secret, unfair competition, and other applicable laws. The author and editors of this work have added value to the underlying factual material herein through one or more of the follow- ing: unique and original selection, coordination, expression, arrangement, and classification of the information.