Jerusalem and the Christianization of Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature A Brief Study Ritgerð til MA-prófs í íslenskum miðaldafræðum Li Tang Kt.: 270988-5049 Leiðbeinandi: Torfi H. Tulinius September 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my supervisor, Torfi H. Tulinius for his confidence and counsels which have greatly encouraged my writing of this paper. Because of this confidence, I have been able to explore a domain almost unstudied which attracts me the most. Thanks to his counsels (such as his advice on the “Blóð-Egill” Episode in Knýtlinga saga and the reading of important references), my work has been able to find its way through the different numbers. My thanks also go to Haraldur Bernharðsson whose courses on Old Icelandic have been helpful to the translations in this paper and have become an unforgettable memory for me. I‟m indebted to Moritz as well for our interesting discussion about the translation of some paragraphs, and to Capucine and Luis for their meticulous reading. Any fault, however, is my own. Abstract It is generally agreed that some numbers such as three and nine which appear frequently in the two Eddas hold special significances in Norse mythology. Furthermore, numbers appearing in sagas not only denote factual quantity, but also stand for specific symbolic meanings. This tradition of number symbolism could be traced to Pythagorean thought and to St. Augustine‟s writings. But the result in Old Norse literature is its own system influenced both by Nordic beliefs and Christianity. This double influence complicates the intertextuality in the light of which the symbolic meanings of numbers should be interpreted. -

18Th Viking Congress Denmark, 6–12 August 2017

18th Viking Congress Denmark, 6–12 August 2017 Abstracts – Papers and Posters 18 TH VIKING CONGRESS, DENMARK 6–12 AUGUST 2017 2 ABSTRACTS – PAPERS AND POSTERS Sponsors KrKrogagerFondenoagerFonden Dronning Margrethe II’s Arkæologiske Fond Farumgaard-Fonden 18TH VIKING CONGRESS, DENMARK 6–12 AUGUST 2017 ABSTRACTS – PAPERS AND POSTERS 3 Welcome to the 18th Viking Congress In 2017, Denmark is host to the 18th Viking Congress. The history of the Viking Congresses goes back to 1946. Since this early beginning, the objective has been to create a common forum for the most current research and theories within Viking-age studies and to enhance communication and collaboration within the field, crossing disciplinary and geographical borders. Thus, it has become a multinational, interdisciplinary meeting for leading scholars of Viking studies in the fields of Archaeology, History, Philology, Place-name studies, Numismatics, Runology and other disciplines, including the natural sciences, relevant to the study of the Viking Age. The 18th Viking Congress opens with a two-day session at the National Museum in Copenhagen and continues, after a cross-country excursion to Roskilde, Trelleborg and Jelling, in the town of Ribe in Jylland. A half-day excursion will take the delegates to Hedeby and the Danevirke. The themes of the 18th Viking Congress are: 1. Catalysts and change in the Viking Age As a historical period, the Viking Age is marked out as a watershed for profound cultural and social changes in northern societies: from the spread of Christianity to urbanisation and political centralisation. Exploring the causes for these changes is a core theme of Viking Studies. -

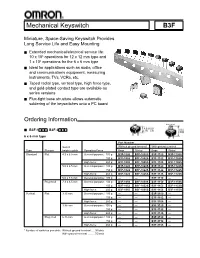

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F Miniature, Space-Saving Keyswitch Provides Long Service Life and Easy Mounting ■ Extended mechanical/electrical service life: 10 x 106 operations for 12 x 12 mm type and 1 x 106 operations for the 6 x 6 mm type ■ Ideal for applications such as audio, office and communications equipment, measuring instruments, TVs, VCRs, etc. ■ Taped radial type, vertical type, high force type, and gold-plated contact type are available as series versions ■ Flux-tight base structure allows automatic soldering of the keyswitches onto a PC board Ordering Information Flat Projected ■ B3F-1■■■, B3F-3■■■ 6 x 6 mm type Part Number Switch Without ground terminal With ground terminal Type Plunger height x pitch Operating Force Bags Sticks* Bags Sticks* Standard Flat 4.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1000 B3F-1000S B3F-1100 B3F-1100S 150 g B3F-1002 B3F-1002S B3F-1102 B3F-1102S High-force: 260 g B3F-1005 B3F-1005S B3F-1105 B3F-1105S 5.0 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1020 B3F-1020S B3F-1120 B3F-1120S 150 g B3F-1022 B3F-1022S B3F-1122 B3F-1122S High-force: 260 g B3F-1025 B3F-1025S B3F-1125 B3F-1125S 5.0 x 7.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-1110 — Projected 7.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1050 B3F-1050S B3F-1150 B3F-1150S 150 g B3F-1052 B3F-1052S B3F-1152 B3F-1152S High-force: 260 g B3F-1055 B3F-1055S B3F-1155 B3F-1155S Vertical Flat 3.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3100 — 150 g — — B3F-3102 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3105 — 3.85 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3120 — 150 g — — B3F-3122 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3125 — Projected 6.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3150 — 150 g — — B3F-3152 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3155 — * Number of switches per stick: Without ground terminal ... -

Herefore, Incentives Typically Offered and Used for Development Would Be Replaced with the EB-5 Investment

Revised – 9/18/17 CITY OF YPSILANTI REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS – ONE SOUTH HURON ST. YPSILANTI, MI 48197 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2017 7:00 p.m. I. CALL TO ORDER – II. ROLL CALL – Council Member Bashert P A Council Member Robb P A Mayor Pro-Tem Brown P A Council Member Vogt P A Council Member Murdock P A Mayor Edmonds P A Council Member Richardson P A III. INVOCATION – IV. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE – “I pledge allegiance to the flag, of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” V. AGENDA APPROVAL – VI. INTRODUCTIONS – VII. AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION – VIII. REMARKS BY THE MAYOR – IX. PUBLIC HEARING – International Village - Water Street A. Resolution No. 2017-208, approving purchase agreement. B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-209, close public hearing X. PRESENTATIONS – Discussion of Easement Agreement with Michigan Advocacy Program on 15 N. Washington. XI. ORDINANCES – FIRST READING – Ordinance No. 1294 An ordinance to rezone 75 Catherine from Core Neighborhood to Production, Manufacturing & Distribution. A. Resolution No. 2017-210, determination B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-211, close public hearing 1 XII. CONSENT AGENDA – Resolution No. 2017-212 1. Resolution No. 2017–213, approving minutes of August 22 and September 5, 2017. 2. Resolution No. 2017-214, approving the issuance of a blanket permit for window signs of any size for the month of October for businesses that participate with the Eastern Michigan University’s “Follow the Green & White Road” homecoming spirit project. -

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20040245547A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2004/0245547 A1 Stipe (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 9, 2004 (54) ULTRA LOW-COST SOLID-STATE MEMORY Publication Classi?cation (75) Inventor; Barry Cushing Stipe, San Jose, CA (51) Int. Cl.7 ................................................ .. H01L 31/109 (Us) (52) US. Cl. ............................................................ .. 257/200 Correspondence Address: (57) ABSTRACT JOSEPH P. CURTIN . A three-dimensional solid-state memory is formed from a plurality of bit lines, a plurality of layers, a plurality of tree ’ structures and a plurality of plate lines. Bit lines extend in a (73) A551 nee, Hitachi Global Stora e Technolo ies ?rst direction in a ?rst plane. Each layer includes an array of g ' B V AZ Amsterdam g memory cells, such as ferroelectric or hysteretic-resistor ' " memory cells. Each tree structure corresponds to a bit line, (21) APPL NO: 10/751 740 has a trunk portion and at least one branch portion. The trunk ’ portion of each tree structure extends from a corresponding (22) Filed; Jam 5, 2004 bit line, and each tree structure corresponds to a plurality of layers. Each branch portion corresponds to at least one layer Related US, Application Data and extends from the trunk portion of a tree structure. Plate lines correspond to at least one layer and overlap the branch (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 10/453,137, portion of each tree structure in at least one roW of tree ?led on Jun. 3, 2003, noW abandoned. structures at a plurality of intersection regions. SRIIIIII DRAM HIIIJ FLASH PROBE GUM MTJ-MRAM 3D-MHAM MATRIX ITFBRIIM GT FERAM 001 size 50F? 012 512 502 502 5F? 002 5e? 512 002 502 Minimum "1" 100m 300m 100m 30 0m 311m 100m 40 nm 400m 10 nm 100m 100m MEX. -

The Perfect Choice! Salzgitter – Salzgitter – Die Bunte Familienstadt a Town of Striking Variety

Salzgitter – the perfect choice! Salzgitter – Salzgitter – die bunte Familienstadt a town of striking variety Salzgitter, die viertgrünste Stadt Deutschlands besticht Salzgitter is charmingly located among the Lower Saxon durch das große und naturnahe Freizeitangebot und foothills of the Harz Mountains. The fact that the town’s 31 freundliches Wohnen im Grünen. Die vielen Bürgerfeste, districts are surrounded by forests and fields means that Open Airs im Schloss Salder, aber auch die mittelalterli- nature is only ever a stone’s throw away. chen Märkte auf den Burgen Lichtenberg und Gebhards- hagen machen die Stadt so Lebens- und Liebenswert. Lake Salzgitter ranks as one of the town’s biggest attrac- tions, and has earned a reputation as the region’s premier Der Salzgitter See mit der Wasserskianlage, dem Piraten- water sports destination. It is located right next to the cen- spielplatz, der Eishalle und vielen weiteren kostenlosen tre of Lebenstedt – a large, modern district connected to Sporteinrichtungen ist das Aushängeschild in der Region the historic spa town of Salzgitter-Bad by the walker and und liegt in unmittelbarer Nähe des Stadtzentrums Le- cyclist-friendly Salzgitter Höhenzug Hills. Salzgitter-Bad is benstedt. Auch die kostenlosen Kindergärten sind einzig- the town’s second-largest district and greets visitors with artig in der Region und unterstreichen besonders die Fa- an enchanting collection of half-timbered buildings. Its milienfreundlichkeit. Der moderne Stadtteil Lebenstedt many smaller, village-like neighbourhoods also play an wird über den Lichtenberger Höhenzug, der zum Wan- important role in lending the town a special charm. dern und Mountenbiken einlädt, mit dem historischen Salzgitter Bad verbunden. -

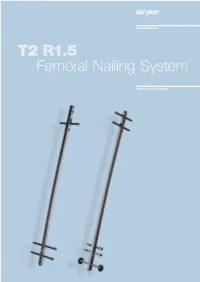

T2 R1.5 Femoral Nailing System

T2 R1.5 Femoral Nailing System Operative Technique Femoral Nailing System Contributing Surgeons Prof. Dr. med. Volker Bühren Chief of Surgical Services Medical Director of Murnau Trauma Center Murnau Germany Joseph D. DiCicco III, D. O. Director Orthopaedic Trauma Service Good Samaritan Hospital Dayton, Ohio Associate Clinical Professor of Orthopeadic Surgery Ohio University and Wright State University USA Thomas G. DiPasquale, D. O. Medical Director, Orthopedic Trauma Services Director, Orthopedic Trauma Fellowship and This publication sets forth detailed Orthopedic Residency Programs recommended procedures for using York Hospital Stryker Osteosynthesis devices and York instruments. USA It offers guidance that you should heed, but, as with any such technical guide, each surgeon must consider the particular needs of each patient and make appropriate adjustments when and as required. A workshop training is required prior to first surgery. All non-sterile devices must be cleaned and sterilized before use. Follow the instructions provided in our reprocessing guide (L24002000). Multi-component instruments must be disassembled for cleaning. Please refer to the corresponding assembly/ disassembly instructions. See package insert (L22000007) for a complete list of potential adverse effects, contraindications, warnings and precautions. The surgeon must discuss all relevant risks, including the finite lifetime of the device, with the patient, when necessary. Warning: Fixation Screws: Stryker Ostreosynthesis bone screws are not approved or intended for screw attachment or fixation to the posterior elements (pedicles) of the cervical, thoracic or lumbar spine. 2 Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 Implant Features 4 Instrument Features 6 References 6 2. Indications, Precautions and Contraindications 7 Indications 7 Precautions 7 Relative Contraindications 7 3. -

Norman Identity and Historiography in the 11Th-12Th Centuries

Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 5 2019 The Comedia Normannorum: Norman Identity and Historiography in the 11th-12th Centuries Patrick Stroud Wabash College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur Recommended Citation Stroud, Patrick (2019) "The Comedia Normannorum: Norman Identity and Historiography in the 11th-12th Centuries," Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 5 , Article 10. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol5/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, VOLUME 5 THE COMEDIA NORMANNORUM: NORMAN IDENTITY AND HISTORIOGRAPHY IN THE 11TH-12TH CENTURIES PATRICK STROUD, WABASH COLLEGE MENTOR: STEPHEN MORILLO Introduction—How Symbols and Ethnography Tie to Historical Myth Since the 1970s, historians have tried many different methodologies for exploring texts. Because multiple paradigms tempt the historian’s gaze, medieval texts can often befuddle readers in their hagiographies and chronologies. At the same time, these texts also give the historian a unique opportunity in the form of cultural insight. In his 1995 work Making History: The Normans and their Historians in Eleventh-Century Italy, Kenneth Baxter Wolf discusses a text’s role in medieval historiography. A professor of History at Pomona College, Wolf divides historical commentary on medieval primary sources into two ends of a spectrum. While one end worries itself on the accuracy and classical “truth” of a source, the other end, postmodern historiography, uses historical records “to tell us how the people who wrote them conceived of the events occurring in the world around them.”1 The historian treats a medieval text as a launching pad for cultural analysis. -

Battle of Stiklestad: Supporting Virtual Heritage with 3D Collaborative Virtual Environments and Mobile Devices in Educational Settings

Archived at the Flinders Academic Commons http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/ Originally published at: Proceedings of Mobile and Ubiquitous Technologies for Learning (UBICOMM 07), Papeete, Tahiti, 04-09 November 2007, pp. 197-203 Copyright © 2007 IEEE. Published version of the paper reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or to reuse any copyrighted component of this work in other works must be obtained from the IEEE. International Conference on Mobile Ubiquitous Computing, Systems, Services and Technologies Battle of Stiklestad: Supporting Virtual Heritage with 3D Collaborative Virtual Environments and Mobile Devices in Educational Settings Ekaterina Prasolova-Førland Theodor G. Wyeld Monica Divitini, Anders Lindås Norwegian University of Adelaide University Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Adelaide, Australia Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway [email protected] Trondheim, Norway [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Abstract sociological significance. From reconstructions recording historical information about these sites a 3D Collaborative Virtual Environments (CVEs) realistic image of how these places might have looked in the past can be created. This also allows inhabiting have been widely used for preservation of cultural of these reconstructed spaces with people and artifacts heritage, also in an educational context. This paper for users to interact with. All these features can act as a presents a project where 3D CVE is augmented with valuable addition to a ‘traditional’ educational process mobile devices in order to support a collaborative in history and related subjects. -

Hildesheim.Pdf

Auftraggeber: Stadt Hildesheim Projektverantwortliche: Andrea Döring Stadtbaurätin Sandra Brouër Fachbereichsleiterin Stadtplanung und Stadtentwicklung Patrick Prause Bereich Stadtentwicklung – Verkehrsplanung Michael Veenhuis Bereichsleiter Stadtentwicklung – Projektleitung Auftragnehmer: Dr. Peter Bischoff SHP Ingenieure GbR AP 1, 3, 5 Melissa Latzel SHP Ingenieure GbR AP 1, 3, 5 Jürgen Allesch eM-Pro Elektromobilität GmbH AP 2 Burkhard Eberwein eM-Pro Elektromobilität GmbH AP 2 Helge Spies LNC LogisticNetwork Consultants GmbH AP 4 Dag Rüdiger LNC LogisticNetwork Consultants GmbH AP 4 Matthias Puffe Becker Büttner Held Consulting AG AP 6, 8 Dr. Florian Umlauf Becker Büttner Held Consulting AG AP 6, 8 Marius Goffart Becker Büttner Held Consulting AG AP 6, 8 Matthias Hartwig Institut für Klimaschutz, Energie und Mobilität AP 7 Felix Nowack Institut für Klimaschutz, Energie und Mobilität AP 7 Oskar Schumacher Institut für Klimaschutz, Energie und Mobilität AP 7 Projektleitung: Dr. Florian Umlauf Projektsteuerung: Andrea Döring Sandra Brouër Dr. Peter Bischoff Michael Veenhuis Dr. Florian Umlauf Matthias Puffe Green City Plan Hildesheim Verzeichnisse II Inhaltsverzeichnis Abbildungsverzeichnis ...................................................................................................... IX Tabellenverzeichnis........................................................................................................... X 1 Kurzzusammenfassung .............................................................................................. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal .