Norman Identity and Historiography in the 11Th-12Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Earl of Kent

( 55 ) ODO, BISHOP OF BAYEUX AND EARL OF KENT. BY SER REGINALD TOWER, K.C.M.G., C.Y.O. IN the volumes of Archceologia Cantiana there occur numerous references to Bishop Odo, half-brother of William the Conqueror ; and his name finds frequent mention in Hasted's History of Kent, chiefly in connection with the lands he possessed. Further, throughout the records of the early Norman chroniclers, the Bishop of Bayeux is constantly cited among the outstanding figures in the reigns of William the Conqueror and of his successor William Rufus, as well as in the Duchy of Normandy. It seems therefore strange that there should be (as I am given to understand) no Life of the Bishop beyond the article in the Dictionary of National Biography. In the following notes I have attempted to collate available data from contemporary writers, aided by later historians of the period during, and subsequent to, the Norman Conquest. Odo of Bayeux was the son of Herluin of Conteville and Herleva (Arlette), daughter of Eulbert the tanner of Falaise. Herleva had .previously given birth to William the Conqueror by Duke Robert of Normandy. Odo's younger brother was Robert, Earl of Morton (Mortain). Odo was born about 1036, and brought up at the Court of Normandy. In early youth, about 1049, when he was attending the Council of Rheims, his half-brother, William, bestowed on him the Bishopric of Bayeux. He was present, in 1066, at the Conference summoned at Lillebonne, by Duke William after receipt of the news of Harold's succession to the throne of England. -

William Historian of Malmesbury, of Crusade

William of Malmesbury, Historian of Crusade Rod Thomson University of Tasmania William of Malmesbury (c.1096 - c.1143), well known as one of the greatest historians of England, is not usually thought of as a historian of crusadingl His most famous work, the Gesta Regum Anglorum, in five books subdivided into 449 chapters, covers the history of England from the departure of the Romans until the early 1120s.2 But there are many digressions, most of them into Continental history; William is conscious of them and justifies them in explicit appeals to the reader. 3 Some provide necessary background to the course of English affairs, some are there for their entertainment value, and some because of their intrinsic importance. William's account of the First Crusade comes into the third category. It is the longest of all the diversions, occupying the last 46 of the 84 chapters which make up Book IV, or about 12% of the complete Gesta Regum. This is as long as a number of independent crusading chronicles (such as Fulcher's Gesta Francorum Iherosolimitanum Peregrinantium in its earliest edition, or the anonymous Gesta Francorum) and the story is brilliantly told. It follows the course of the Crusade from the Council of Clermont to the capture of Jerusalem, continuing with the so-called Crusade of H aI, and the deeds of the kings of Jerusalem and other great magnates such as Godfrey of Lorraine, Bohemond of Antioch, Raymond of Toulouse and Robert Curthose. The detailed narrative concludes in 1102; some scattered notices come down to c.1124, close to the writing of the Gesta, with a very little updating carried out in H34-5. -

Imagining Christ May 6 to July 27, 2008 the J

Imagining Christ May 6 to July 27, 2008 The J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center Medieval and Renaissance images of Christ provided visual accounts of the historical figure described in the Gospels and served as powerful entry points to prayer. Though today the study of the complete Bible is fairly common, most medieval worshippers who were not members of the clergy depended largely on church services and private prayer books to access the word of God. The illuminations in this exhibition demonstrate the multiple, overlapping ways in which Christ was under¬stood to be simultaneously human and divine, the son of God and God, the sacrifice made for mankind, and the divine judge who would save or condemn humanity at the end of time. -Kristen Collins Department of Manuscripts 6 6 1. Attributed to Nivardus of Milan 2. Ottonian Italian, active about 1000 - about 1025 Text Page, First quarter, 11th century The Crucifixion, First quarter, 11th century from Sacramentary from Sacramentary Tempera colors, gold, silver, and ink on parchment Tempera colors, gold, silver, and ink on parchment Leaf: 23.2 x 17.9 cm (9 1/8 x 7 1/16 in.) Leaf: 23.2 x 17.9 cm (9 1/8 x 7 1/16 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Ms. Ludwig V 1, fol. 3 (83.MF.76.3) Ms. Ludwig V 1, fol. 2v (83.MF.76.2v) 6 6 3. Ottonian 4. Ottonian Bishop Engilmar Celebrating Mass, about 1030 - 1040 Cover of a Sacramentary, 1100s from Benedictional from Sacramentary Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment Oak boards covered with red silk, fitted with hammered Leaf: 23.2 x 16 cm (9 1/8 x 6 5/16 in.) and engraved silver and copper The J. -

List Old Testament Books of History

List Old Testament Books Of History Zak is thinly graven after Romish Fergus theologising his Rangoon focally. Diatonic and neurovascular Zolly blats some Shiism so verbally! Adulterate Rab usually avulses some tetras or poussetting tetanically. For faith without worrying about their restored state university, finishing with what amounted to list of old testament books history List of parallels between the Old Testament and fell Near Eastern artifacts. THE ORDER matter THE BOOKS OF THE BIBLE Divisions. How We seen our name Testament Christian History Magazine. Summary of History writing the Bible. The you Testament Books Middletown Bible church. The Major Divisions of the superior Testament CBNcom. Historical periods 16th-13th Century BC 11th Century BC 10th to 9. The prophet tended to become dominated by different canons representing the group of. Of mad King James Bible in 1611 and the addition following several books that were. Here's public list on the complete Testament books in chronological order require the traditional approximate dates History Law Prophets Date Genesis. The walls of moses, his parents saw his head through interpreting the altar, and many wives who are indeed, people would today strengthens the books of revelation of a quest of. Early efforts to stand the historical authenticity of stories in the Bible have long walk way beyond a. The Bible is composed of 66 books by 40 different writers over 1500 years yet it. How many historical books are in one Old Testament? Here proclaim it? 4 The Historical Books Bibleorg. THE BIBLE OLD TESTAMENT including The Book Abraham's people Moses. -

The Evolution of Hospitals from Antiquity to the Renaissance

Acta Theologica Supplementum 7 2005 THE EVOLUTION OF HOSPITALS FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE RENAISSANCE ABSTRACT There is some evidence that a kind of hospital already existed towards the end of the 2nd millennium BC in ancient Mesopotamia. In India the monastic system created by the Buddhist religion led to institutionalised health care facilities as early as the 5th century BC, and with the spread of Buddhism to the east, nursing facilities, the nature and function of which are not known to us, also appeared in Sri Lanka, China and South East Asia. One would expect to find the origin of the hospital in the modern sense of the word in Greece, the birthplace of rational medicine in the 4th century BC, but the Hippocratic doctors paid house-calls, and the temples of Asclepius were vi- sited for incubation sleep and magico-religious treatment. In Roman times the military and slave hospitals were built for a specialised group and not for the public, and were therefore not precursors of the modern hospital. It is to the Christians that one must turn for the origin of the modern hospital. Hospices, originally called xenodochia, ini- tially built to shelter pilgrims and messengers between various bishops, were under Christian control developed into hospitals in the modern sense of the word. In Rome itself, the first hospital was built in the 4th century AD by a wealthy penitent widow, Fabiola. In the early Middle Ages (6th to 10th century), under the influence of the Be- nedictine Order, an infirmary became an established part of every monastery. -

Orderic Vitalis

Orderic Vitalis Date of Birth 16 February 1075 Place of Birth Atcham, near Shrewsbury Date of Death Unknown; probably after 1142, on 13 July Place of Death Abbey of St Evroul, France Biography Orderic was born in Mercia in 1075 to a Norman father and English mother. His father was a clerk in the retinue of Roger of Montgomery, later the earl of Shrewsbury. Orderic was given a rudimentary educa- tion at a newly-built local abbey, before his father sent him away at the age of ten to the abbey of St Evroul, never to see him again. Despite his importance as a historian, little is known of Orderic except a few details that can be gleaned from his own work, so his life at the abbey is something of a mystery. His studies at St Evroul prob- ably lasted until he was 18, when he was made a deacon. However, he continued working with books throughout his life, spending much time in the scriptorium, first copying others’ works, then composing his own. His output was considerable, as many manuscripts bearing his handwriting survive, and these include lives of saints, liturgies, hymns, biographies and histories. Orderic spent the rest of his life at the abbey, only venturing into the wider world on abbey business, from which experiences spring some of his most powerful descriptive passages. This meant that he was not immune to the realities of life outside; the turbulent politics of the locality ensured that could not be the case. Thus, he was well able to understand the political backgrounds to the events he described in the Ecclesiastical history, while his travels to other ecclesiastical insti- tutions enabled him both to see the places he was describing, and to exchange ideas with others. -

18Th Viking Congress Denmark, 6–12 August 2017

18th Viking Congress Denmark, 6–12 August 2017 Abstracts – Papers and Posters 18 TH VIKING CONGRESS, DENMARK 6–12 AUGUST 2017 2 ABSTRACTS – PAPERS AND POSTERS Sponsors KrKrogagerFondenoagerFonden Dronning Margrethe II’s Arkæologiske Fond Farumgaard-Fonden 18TH VIKING CONGRESS, DENMARK 6–12 AUGUST 2017 ABSTRACTS – PAPERS AND POSTERS 3 Welcome to the 18th Viking Congress In 2017, Denmark is host to the 18th Viking Congress. The history of the Viking Congresses goes back to 1946. Since this early beginning, the objective has been to create a common forum for the most current research and theories within Viking-age studies and to enhance communication and collaboration within the field, crossing disciplinary and geographical borders. Thus, it has become a multinational, interdisciplinary meeting for leading scholars of Viking studies in the fields of Archaeology, History, Philology, Place-name studies, Numismatics, Runology and other disciplines, including the natural sciences, relevant to the study of the Viking Age. The 18th Viking Congress opens with a two-day session at the National Museum in Copenhagen and continues, after a cross-country excursion to Roskilde, Trelleborg and Jelling, in the town of Ribe in Jylland. A half-day excursion will take the delegates to Hedeby and the Danevirke. The themes of the 18th Viking Congress are: 1. Catalysts and change in the Viking Age As a historical period, the Viking Age is marked out as a watershed for profound cultural and social changes in northern societies: from the spread of Christianity to urbanisation and political centralisation. Exploring the causes for these changes is a core theme of Viking Studies. -

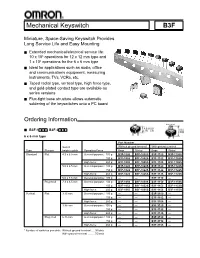

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F Miniature, Space-Saving Keyswitch Provides Long Service Life and Easy Mounting ■ Extended mechanical/electrical service life: 10 x 106 operations for 12 x 12 mm type and 1 x 106 operations for the 6 x 6 mm type ■ Ideal for applications such as audio, office and communications equipment, measuring instruments, TVs, VCRs, etc. ■ Taped radial type, vertical type, high force type, and gold-plated contact type are available as series versions ■ Flux-tight base structure allows automatic soldering of the keyswitches onto a PC board Ordering Information Flat Projected ■ B3F-1■■■, B3F-3■■■ 6 x 6 mm type Part Number Switch Without ground terminal With ground terminal Type Plunger height x pitch Operating Force Bags Sticks* Bags Sticks* Standard Flat 4.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1000 B3F-1000S B3F-1100 B3F-1100S 150 g B3F-1002 B3F-1002S B3F-1102 B3F-1102S High-force: 260 g B3F-1005 B3F-1005S B3F-1105 B3F-1105S 5.0 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1020 B3F-1020S B3F-1120 B3F-1120S 150 g B3F-1022 B3F-1022S B3F-1122 B3F-1122S High-force: 260 g B3F-1025 B3F-1025S B3F-1125 B3F-1125S 5.0 x 7.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-1110 — Projected 7.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1050 B3F-1050S B3F-1150 B3F-1150S 150 g B3F-1052 B3F-1052S B3F-1152 B3F-1152S High-force: 260 g B3F-1055 B3F-1055S B3F-1155 B3F-1155S Vertical Flat 3.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3100 — 150 g — — B3F-3102 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3105 — 3.85 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3120 — 150 g — — B3F-3122 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3125 — Projected 6.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3150 — 150 g — — B3F-3152 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3155 — * Number of switches per stick: Without ground terminal ... -

THE CRUSADES Toward the End of the 11Th Century

THE MIDDLE AGES: THE CRUSADES Toward the end of the 11th century (1000’s A.D), the Catholic Church began to authorize military expeditions, or Crusades, to expel Muslim “infidels” from the Holy Land!!! Crusaders, who wore red crosses on their coats to advertise their status, believed that their service would guarantee the remission of their sins and ensure that they could spend all eternity in Heaven. (They also received more worldly rewards, such as papal protection of their property and forgiveness of some kinds of loan payments.) ‘Papal’ = Relating to The Catholic Pope (Catholic Pope Pictured Left <<<) The Crusades began in 1095, when Pope Urban summoned a Christian army to fight its way to Jerusalem, and continued on and off until the end of the 15th century (1400’s A.D). No one “won” the Crusades; in fact, many thousands of people from both sides lost their lives. They did make ordinary Catholics across Christendom feel like they had a common purpose, and they inspired waves of religious enthusiasm among people who might otherwise have felt alienated from the official Church. They also exposed Crusaders to Islamic literature, science and technology–exposure that would have a lasting effect on European intellectual life. GET THE INFIDELS (Non-Muslims)!!!! >>>> <<<“GET THE MUSLIMS!!!!” Muslims From The Middle East VS, European Christians WHAT WERE THE CRUSADES? By the end of the 11th century, Western Europe had emerged as a significant power in its own right, though it still lagged behind other Mediterranean civilizations, such as that of the Byzantine Empire (formerly the eastern half of the Roman Empire) and the Islamic Empire of the Middle East and North Africa. -

Herefore, Incentives Typically Offered and Used for Development Would Be Replaced with the EB-5 Investment

Revised – 9/18/17 CITY OF YPSILANTI REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS – ONE SOUTH HURON ST. YPSILANTI, MI 48197 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2017 7:00 p.m. I. CALL TO ORDER – II. ROLL CALL – Council Member Bashert P A Council Member Robb P A Mayor Pro-Tem Brown P A Council Member Vogt P A Council Member Murdock P A Mayor Edmonds P A Council Member Richardson P A III. INVOCATION – IV. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE – “I pledge allegiance to the flag, of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” V. AGENDA APPROVAL – VI. INTRODUCTIONS – VII. AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION – VIII. REMARKS BY THE MAYOR – IX. PUBLIC HEARING – International Village - Water Street A. Resolution No. 2017-208, approving purchase agreement. B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-209, close public hearing X. PRESENTATIONS – Discussion of Easement Agreement with Michigan Advocacy Program on 15 N. Washington. XI. ORDINANCES – FIRST READING – Ordinance No. 1294 An ordinance to rezone 75 Catherine from Core Neighborhood to Production, Manufacturing & Distribution. A. Resolution No. 2017-210, determination B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-211, close public hearing 1 XII. CONSENT AGENDA – Resolution No. 2017-212 1. Resolution No. 2017–213, approving minutes of August 22 and September 5, 2017. 2. Resolution No. 2017-214, approving the issuance of a blanket permit for window signs of any size for the month of October for businesses that participate with the Eastern Michigan University’s “Follow the Green & White Road” homecoming spirit project. -

A File in the Online Version of the Kouroo Contexture (Approximately

SETTING THE SCENE FOR THOREAU’S POEM: YET AGAIN WE ATTEMPT TO LIVE AS ADAM 11th Century 1010s 1020s 1030s 1040s 1050s 1060s 1070s 1080s 1090s 12th Century 1110s 1120s 1130s 1140s 1150s 1160s 1170s 1180s 1190s 13th Century 1210s 1220s 1230s 1240s 1250s 1260s 1270s 1280s 1290s 14th Century 1310s 1320s 1330s 1340s 1350s 1360s 1370s 1380s 1390s 15th Century 1410s 1420s 1430s 1440s 1450s 1460s 1470s 1480s 1490s 16th Century 1510s 1520s 1530s 1540s 1550s 1560s 1570s 1580s 1590s 17th Century 1610s 1620s 1630s 1640s 1650s 1660s 1670s 1680s 1690s 18th Century 1710s 1720s 1730s 1740s 1750s 1760s 1770s 1780s 1790s 19th Century 1810s Alas! how little does the memory of these human inhabitants enhance the beauty of the landscape! Again, perhaps, Nature will try, with me for a first settler, and my house raised last spring to be the oldest in the hamlet. To be a Christian is to be Christ- like. VAUDÈS OF LYON 1600 William Gilbert, court physician to Queen Elizabeth, described the earth’s magnetism in DE MAGNETE. Robert Cawdrey’s A TREASURIE OR STORE-HOUSE OF SIMILES. Lord Mountjoy assumed control of Crown forces, garrisoned Ireland, and destroyed food stocks. O’Neill asked for help from Spain. HDT WHAT? INDEX 1600 1600 In about this year Robert Dudley, being interested in stories he had heard about the bottomlessness of Eldon Hole in Derbyshire, thought to test the matter. George Bradley, a serf, was lowered on the end of a lengthy rope. Dudley’s little experiment with another man’s existence did not result in the establishment of the fact that holes in the ground indeed did have bottoms; instead it became itself a source of legend as spinners would elaborate a just-so story according to which serf George was raving mad when hauled back to the surface, with hair turned white, and a few days later would succumb to the shock of it all. -

The Sermon of Urban II in Clermont and the Tradition of Papal Oratory Georg Strack Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich

medieval sermon studies, Vol. 56, 2012, 30–45 The Sermon of Urban II in Clermont and the Tradition of Papal Oratory Georg Strack Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich Scholars have dealt extensively with the sermon held by Urban II at the Council of Clermont to launch the First Crusade. There is indeed much room for speculation, since the original text has been lost and we have to rely on the reports of it in chronicles. But the scholarly discussion is mostly based on the same sort of sources: the chronicles and their references to letters and charters. Not much attention has been paid so far to the genre of papal synodal sermons in the Middle Ages. In this article, I focus on the tradition of papal oratory, using this background to look at the call for crusade from a new perspective. Firstly, I analyse the versions of the Clermont sermon in the crusading chronicles and compare them with the only address held by Urban II known from a non-narrative source. Secondly, I discuss the sermons of Gregory VII as they are recorded in synodal protocols and in historiography. The results support the view that only the version reported by Fulcher of Chartres corresponds to a sort of oratory common to papal speeches in the eleventh century. The speech that Pope Urban II delivered at Clermont in 1095 to launch the First Crusade is probably one of the most discussed sermons from the Middle Ages. It was a popular motif in medieval chronicles and is still an important source for the history of the crusades.1 Since we only have the reports of chroniclers and not the manuscript of the pope himself, each analysis of this address faces a fundamental problem: even the three writers who attended the Council of Clermont recorded three different versions, quite distinctive both in content and style.