2020 Ambient Air Monitoring Network 5-Year Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Conditions Placed on PGV for Start-Up Operations

In-formation. Bulletin Drilling Resumption 'at Puna Geothermal Venture Published by the County of Hawaii and State of Hawaii • March 1992 New conditions placed on PGV for start-up operations Task force bans open venting, tightens drilling requirements, cuts emissions After meetingthe termsand conditions prioritywiththenewrequirements andthe of a major overhaul on drilling, safety commitmentof more than $1.6 millionin requirements and enforcement, Puna State fundsto ensure compliance." Geothermal Venture (PGV) has received The County suspended drilling permission to complete its 25-megawatt operations at the facility in June, 1991. electric power plant in Kapoho. afteran uncontrolled wellblowout. Since The new criteria were issued in a then a County-State task force and Geothermal Management Plan prepared independent consultants· have developed by a joint County-State task force. The the Geothermal Management Plan to plan tightens dr..iing requirements. addressa wide rangeof concerns. improvesemergencyresponseprocedures, The Management Plan includes: This sketch shows what will be Hawaii's first commercial geothermal power plant. improves emission requirements for • a ban on the open venting of new or The facility in Kapoho will deliver 25 megawatts to Hawaii Electric Light Co. hydrogen sulfide and noise, upgrades existing wells, monitoring equipmentand adds staff to -. an upgrade of the air monitoring ensure enforcement. program to meet the recommendations $1.6 million released to staff and equip "Iamadvisedthatthenewrequirements of independentconsultants, -

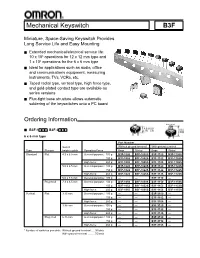

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F Miniature, Space-Saving Keyswitch Provides Long Service Life and Easy Mounting ■ Extended mechanical/electrical service life: 10 x 106 operations for 12 x 12 mm type and 1 x 106 operations for the 6 x 6 mm type ■ Ideal for applications such as audio, office and communications equipment, measuring instruments, TVs, VCRs, etc. ■ Taped radial type, vertical type, high force type, and gold-plated contact type are available as series versions ■ Flux-tight base structure allows automatic soldering of the keyswitches onto a PC board Ordering Information Flat Projected ■ B3F-1■■■, B3F-3■■■ 6 x 6 mm type Part Number Switch Without ground terminal With ground terminal Type Plunger height x pitch Operating Force Bags Sticks* Bags Sticks* Standard Flat 4.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1000 B3F-1000S B3F-1100 B3F-1100S 150 g B3F-1002 B3F-1002S B3F-1102 B3F-1102S High-force: 260 g B3F-1005 B3F-1005S B3F-1105 B3F-1105S 5.0 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1020 B3F-1020S B3F-1120 B3F-1120S 150 g B3F-1022 B3F-1022S B3F-1122 B3F-1122S High-force: 260 g B3F-1025 B3F-1025S B3F-1125 B3F-1125S 5.0 x 7.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-1110 — Projected 7.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1050 B3F-1050S B3F-1150 B3F-1150S 150 g B3F-1052 B3F-1052S B3F-1152 B3F-1152S High-force: 260 g B3F-1055 B3F-1055S B3F-1155 B3F-1155S Vertical Flat 3.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3100 — 150 g — — B3F-3102 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3105 — 3.85 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3120 — 150 g — — B3F-3122 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3125 — Projected 6.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3150 — 150 g — — B3F-3152 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3155 — * Number of switches per stick: Without ground terminal ... -

Herefore, Incentives Typically Offered and Used for Development Would Be Replaced with the EB-5 Investment

Revised – 9/18/17 CITY OF YPSILANTI REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS – ONE SOUTH HURON ST. YPSILANTI, MI 48197 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2017 7:00 p.m. I. CALL TO ORDER – II. ROLL CALL – Council Member Bashert P A Council Member Robb P A Mayor Pro-Tem Brown P A Council Member Vogt P A Council Member Murdock P A Mayor Edmonds P A Council Member Richardson P A III. INVOCATION – IV. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE – “I pledge allegiance to the flag, of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” V. AGENDA APPROVAL – VI. INTRODUCTIONS – VII. AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION – VIII. REMARKS BY THE MAYOR – IX. PUBLIC HEARING – International Village - Water Street A. Resolution No. 2017-208, approving purchase agreement. B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-209, close public hearing X. PRESENTATIONS – Discussion of Easement Agreement with Michigan Advocacy Program on 15 N. Washington. XI. ORDINANCES – FIRST READING – Ordinance No. 1294 An ordinance to rezone 75 Catherine from Core Neighborhood to Production, Manufacturing & Distribution. A. Resolution No. 2017-210, determination B. Open public hearing C. Resolution No. 2017-211, close public hearing 1 XII. CONSENT AGENDA – Resolution No. 2017-212 1. Resolution No. 2017–213, approving minutes of August 22 and September 5, 2017. 2. Resolution No. 2017-214, approving the issuance of a blanket permit for window signs of any size for the month of October for businesses that participate with the Eastern Michigan University’s “Follow the Green & White Road” homecoming spirit project. -

Conversing with Pelehonuamea: a Workshop Combining 1,000+ Years of Traditional Hawaiian Knowledge with 200 Years of Scientific Thought on Kīlauea Volcanism

Conversing with Pelehonuamea: A Workshop Combining 1,000+ Years of Traditional Hawaiian Knowledge with 200 Years of Scientific Thought on Kīlauea Volcanism Open-File Report 2017–1043 Version 1.1, June 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Conversing with Pelehonuamea: A Workshop Combining 1,000+ Years of Traditional Hawaiian Knowledge with 200 Years of Scientific Thought on Kīlauea Volcanism Compiled and Edited by James P. Kauahikaua and Janet L. Babb Open-File Report 2017–1043 Version 1.1, June 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William H. Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 First release: 2017 Revised: June 2017 (ver. 1.1) For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Kauahikaua, J.P., and Babb, J.L., comps. and eds., Conversing with Pelehonuamea—A workshop combining 1,000+ years of traditional Hawaiian knowledge with 200 years of scientific thought on Kīlauea volcanism (ver. -

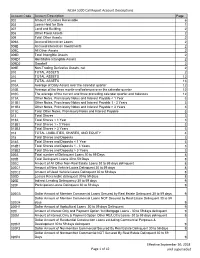

NCUA 5300 Call Report Account Descriptions Page 1 of 42 Effective

NCUA 5300 Call Report Account Descriptions Account Code Account Description Page 002 Amount of Leases Receivable 6 003 Loans Held for Sale 1 007 Land and Building 2 008 Other Fixed Assets 2 009 Total Other Assets 2 009A Accrued Interest on Loans 2 009B Accrued Interest on Investments 2 009C All Other Assets 2 009D Total Intangible Assets 2 009D1 Identifiable Intangible Assets 2 009D2 Goodwill 2 009E Non-Trading Derivative Assets, net 2 010 TOTAL ASSETS 2 010 TOTAL ASSETS 12 010 TOTAL ASSETS 13 010A Average of Daily Assets over the calendar quarter 12 010B Average of the three month-end balances over the calendar quarter 12 010C The average of the current and three preceding calendar quarter-end balances 12 011A Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable < 1 Year 3 011B1 Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable 1 - 3 Years 3 011B2 Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable > 3 Years 3 011C Total Other Notes, Promissory Notes and Interest Payable 3 013 Total Shares 3 013A Total Shares < 1 Year 3 013B1 Total Shares 1 - 3 Years 3 013B2 Total Shares > 3 Years 3 014 TOTAL LIABILITIES, SHARES, AND EQUITY 4 018 Total Shares and Deposits 3 018A Total Shares and Deposits < 1 Year 3 018B1 Total Shares and Deposits 1 - 3 Years 3 018B2 Total Shares and Deposits > 3 Years 3 020A Total number of Delinquent Loans 30 to 59 Days 8 020B Total Delinquent Loans 30 to 59 Days 8 020C Amount of All Other Non-Real Estate Loans 30 to 59 days delinquent 8 020C1 Amount of New Vehicle Loans Delinquent 30 to 59 days 8 020C2 Amount of Used -

HELCO-PGV Quarterly Report – June 1, 2020

June 1, 2020 The Honorable Chair and Members of the Hawai‘i Public Utilities Commission Kekuanao‘a Building, First Floor 465 South King Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96813 Dear Commissioners: Subject: Hawai‘i Electric Light Company, Inc. Rebuild Agreement and PPA Negotiations with Puna Geothermal Venture Quarterly Update The Commission requested in its letter dated May 9, 2019 that Hawai‘i Electric Light Company, Inc. (hereinafter “Hawaiian Electric” or the “Company”)1 keep the Commission updated quarterly, beginning on June 1, 2019, regarding the status of permits required for the Puna Geothermal Venture (“PGV”) facility to come back online (including but not limited to those set forth in Exhibit D, PGV’s Government Approvals, of Exhibit A (Rebuild Agreement) to the Company’s March 8, 2019 letter) and status of negotiations of a restated PPA, and updated, as necessary, regarding any other relevant developments, until the Commission determines otherwise. Since the negotiations are complete and the Amended and Restated Power Purchase Agreement moves forward in Docket No. 2019-0333, the Company provides an update to the Commission on the progress of the PGV rebuild efforts. In response to the Commission’s letter and Orders, Hawaiian Electric respectfully submits its quarterly report on relevant developments for the months of March, April, and May 2020. Status of Permits PGV has provided the Company with an update regarding the status of PGV’s permits as well as a revised Exhibit D, which is attached hereto as Attachment 1. In Summary, every permit required to operate the PGV facility remains, and has remained without interruption, in full force and effect and is active. -

Electric Actuators Vsi-1000 Series

ELECTRIC ACTUATORS TM VSI-1000 SERIES DESCRIPTION VSI-1000 Series Electric Actuators are used on Kele KBV Series butterfly valves to provide two-position (with or without battery backup) or proportional control in a NEMA 4X housing. The VSI-1000 Series comes standard on 8" and larger non-spring return assemblies and on 5" and larger two- position spring return assemblies. They can be ordered on smaller valve assemblies as an option. Standard fea- tures include 2 SPDT fully adjustable auxiliary switches KBV-2-6-E2SO (two-position only), manual override crank, and an inter- assembly includes nal heater to prevent condensation in outdoor installa- VSI-BB1020 actuator tions. SPECIFICATIONS FEATURES Power 120 VAC standard •Lightweight, compact design Models 1005 to 1020 12/24 VDC optional • Two-position or modulating control Models 1005 to 1040 24 VAC optional • Two-position battery-backed models Torque range 347-17,359 in-lb • NEMA 4X watertight, corrosion-resistant housing Motor 120 VAC, 1 phase, 60 Hz; • Integral position indicator enclosed, non-ventilated, high • Space heater standard starting torque, reversible induc- • Two 1/2" conduit connections tion, Class E insulation • Detachable manual override crank Thermal overload Auto reset, embedded • Terminal strip wiring Travel limit switches Cam operated, adjustable SPDT • Worm gear drive, no electro-mechanical brake for open/close stop required • Mounting orientation in any direction Position indicator High-visibility graduated dial • 4-20 mA or 500Ω optional feedback signal Conduit connections -

Norman Identity and Historiography in the 11Th-12Th Centuries

Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 5 2019 The Comedia Normannorum: Norman Identity and Historiography in the 11th-12th Centuries Patrick Stroud Wabash College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur Recommended Citation Stroud, Patrick (2019) "The Comedia Normannorum: Norman Identity and Historiography in the 11th-12th Centuries," Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 5 , Article 10. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol5/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, VOLUME 5 THE COMEDIA NORMANNORUM: NORMAN IDENTITY AND HISTORIOGRAPHY IN THE 11TH-12TH CENTURIES PATRICK STROUD, WABASH COLLEGE MENTOR: STEPHEN MORILLO Introduction—How Symbols and Ethnography Tie to Historical Myth Since the 1970s, historians have tried many different methodologies for exploring texts. Because multiple paradigms tempt the historian’s gaze, medieval texts can often befuddle readers in their hagiographies and chronologies. At the same time, these texts also give the historian a unique opportunity in the form of cultural insight. In his 1995 work Making History: The Normans and their Historians in Eleventh-Century Italy, Kenneth Baxter Wolf discusses a text’s role in medieval historiography. A professor of History at Pomona College, Wolf divides historical commentary on medieval primary sources into two ends of a spectrum. While one end worries itself on the accuracy and classical “truth” of a source, the other end, postmodern historiography, uses historical records “to tell us how the people who wrote them conceived of the events occurring in the world around them.”1 The historian treats a medieval text as a launching pad for cultural analysis. -

Geopowering the West: Hawaii; Why Geothermal?

Geothermal Technologies Program Tapping the Earth’s energy to meet our heat and power needs Kauai A Strong Energy Portfolio Hawaii for a Strong America Niihau Oahu imports oil for about 90 percent Energy effi ciency and clean, renewable of the state’s energy needs. No energy will mean a stronger economy, Molokai Maui other state in the United States a cleaner environment, and greater Lanai is so critically dependent on Pacifi c Ocean Kahoolawe imported oil. Geothermal energy energy independence for America. presently supplies nearly one Working with a wide array of state, Hawaii quarter of the power needs community, industry, and university of the Big Island. The state’s partners, the U.S. Department of policy supports geothermal energy production on the Big Energy’s Offi ce of Energy Effi ciency and Island exclusively for use on Renewable Energy invests in a diverse Why Geothermal? that island. portfolio of energy technologies. Current Development The Hawaiian Islands lie above a employed about 10,000 people to install geological “hot spot” in the earth’s and operate geothermal power plants in mantle that has been volcanically active the United States and abroad, including for the past 70 million years, with the power plant construction and related Island of Hawaii (the “Big Island”) activities such as exploration and having the most recent activity. The Big drilling; indirect employment Island has an obvious, large potential was about 20,000. for geothermal energy resources, both for electrical generation and direct On average from 1997-2001, the utilization. Since the 1976 drilling of Puna Geothermal Venture (PGV) the HGP-A well and the discovery of the 30-megawatt plant on the Big Island Kapoho Geothermal Reservoir in the displaced the need to burn about lower Kilauea East Rift Zone (KERZ), the 475,000 barrels of fuel oil per year. -

Natural Hazards Puna, Island of Hawaii Volcano Hazard Zones Are Ranked from 1 to 9

Natural Hazards Puna, Island of Hawaii Volcano hazard zones are ranked from 1 to 9. Zones ranked 1 Community Development Plan Boundary are the most hazardous area in relation to volcanic activity. Zone 1: Summits and rift zones of Kilauea and Mauna Loa, where vents have been Census Designated Places repeatedly active in historic time. Boundaries are defined by eruptive fissures, cinder cones, pit craters, and graben and caldera faults. Geothermal Zones Zone 2: Areas adjacent to and downslope from Zone 1. Fifteen to twenty-five percent of Zone 2 has been covered by lava since 1800, and 25-75 has been covered Tsunami Evacuation Area within the last 750 years. ! Zone 3: Areas gradationally less hazardous than Zone 2 because of greater distance . Tsunami Evacuation Shelters from recently active vents and/or because the topography makes it less likely that flows will cover these areas. Wao Kele O Puna Forest Reserve The Department of Land and Natural Resources plans on lifting the geothermal designation and abandoning the geothermal well within Wao Kele O Puna boundaries. Creation Date: June 26, 2006 Data Source: The Puna Geothermal Venture, which lies outside Wao Kele O Puna, was Hawaii Statewide GIS Program established in 1993 and plans to continue operations to supplement the Hawaii Electric State Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife Hawaii County Planning Department Company. GHC Bulletin, September 2002 8 Zone 1 Zone 2 Zone 3 Zone 4 2 Zone 5 KEAAU Zone 6 Zone 7 Zone 8 HAWAIIAN KURTISTOWN PARADISE Zone 9 PARK ORCHIDLAND ESTATES HAWAIIAN BEACHES HAWAIIAN ACRES MOUNTAIN V3IEW 2 FERN AINALOA NANAWALE FOREST ESTATES EDEN ROC PAHOA VOLCANO LEILANI FERN FOREST ESTATES 1 2 : Pacific Ocean 5 0 2.5 5 10 Miles 3 This map should not be use for spatial analysis beyond the limits of the data presented, i.e. -

Feasibility of a Geothermal Direct Use Enterprise Park in Puna, Hawaii

Feasibility of a Geothermal Direct Use Enterprise Park in Puna, Hawaii Andrea T. Gill State of Hawaii Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism Strategic Industries Division Tyson Toyama, PE Okahara & Associates, Inc. June 12, 2007 KEYWORDS Direct use, feasibility study, Hawaii, Puna Geothermal Venture, USA ABSTRACT After a public information process which included surveying community members regarding the acceptability of 21 different geothermal direct use applications, four agriculture-related businesses were selected as candidates for a hypothetical 15-acre (6 ha) geothermal enterprise park in the Kapoho/Pohoki area of the island of Hawaii. The applications included greenhouse bottom heating, pasteurization of potting media, biodiesel production, and lumber drying. There was significant community support for the chosen applications, and minimal opposition expressed. An engineering analysis concluded that a direct use enterprise park is technically feasible. Such a park could require up to 11 million Btu/hr (770 kcal/sec) of heat which might be supplied from a high-temperature resource, such as waste heat from a power plant, causing less than a 10° F (5.6° C) decrease in injectate temperature. The analysis was based on this hypothetical scenario, since waste heat is not currently available for direct use. The direct use enterprise park would cost an estimated $12.5 million to develop and construct, and $738,000 per year to operate and maintain. The hypothetical park would only be marginally economically viable, even with significant financial subsidies. Annual revenues are expected to be $1.21 million, based on a $200/acre annual lease rate and a geothermal heat rate priced at $1.32/therm, or half of the prevailing average cost of diesel and propane. -

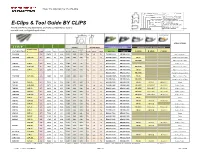

E-Clips & Tool Guide by CLIPS

Phone: 714 809-0194 | Fax: 714 373-4808 3 F = 4" (19.0 mm) XX = LENGTH in 100ths/inch A = 7 / /16" (11.0 mm) A-H = CLIP WIDTH 11 7 E = /16" (17.5 mm) H = /8" (22.0 mm) A-H ZZ = OPENING in 100th s/inch (BLANK) = COLD ROLLED STEEL XX TYPE OF PACKAGING 1006-1010 A = ALUMINUM S–STRIPS CLP–STRIPS C = CUSHIONED (PAPER LINING INSIDE) R–ROLLS CCP–ROLLS G = GALVANIZED L = 4 MIL PVC VINYL COATING E-Clips & Tool Guide BY CLIPS B–BULK (INSIDE) S = STAINLESS STEEL (430) MATERIAL (BLANK) or P = POLYCORD Encore and Hartco clip equivalents, pack/ship configurations, tools to ZZ DESIGNATIONS 74 H 18 S G T = TAPED COLLATION D = DETENT use with each, and typical applications W D PARTS SUPPORT ONLY H APPLICATIONS S T R I P INCHES MILLIMETERS ECLIPSER 2000 SERIES GENUINE HARTCO CLINCH TOOLS HARTCO Clip DEPT ENCORE E-Clip # # #/STRIP CLIPS/CTN LBS/CTN KGS/CTN HEIGHT WIDTH H HEIGHT WIDTH DEPTH ENCORE HARTCO A SERIES B SERIES C SERIES** 52A14SG – 58 15,834 25 11.4 0.32 0.40 0.20 8.2 10 5.1 EA2000-1234 HR2000-1234 0 0 0 Cages, Traps & Wires 64A18SG CLP-15G 47 10,857 24 10.9 0.41 0.43 0.26 10.4 11 6.6 EA2000-1020S HR2000-1020S HR-45i 0 0 Housing Panels, Cages, Cables 64A18SG CLP-15G 47 10,857 24 10.9 0.41 0.43 0.26 10.4 11 6.6 EA2000-1929 HR2000-1929 HR-45TN 0 0 Tight Access Cages & Traps 68H18S CLP-22 47 4,700 22 10.0 0.47 0.86 0.26 11.9 22 6.6 EA2000-6075 HR2000-6075 0 0 0 Bedding, Furniture 71A16SAL CLP-13AL 47 9,400 22 10.0 0.45 0.43 0.26 11.4 11 6.6 EA2000-1929 HR2000-1929 HR-45TN 0 0 Tight Access Cages & Traps 71A18S CLP-13 47 9,400 22 10.0 0.45 0.43 0.26