Examining Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Separatism in Quebec

1 Separatism in Quebec: Off the Agenda but Not Off the Minds of Francophones An Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Politics in Partial Fulfillment of the Honors Program By Sarah Weber 5/6/15 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction 3 Chapter 2. 4 Chapter 3. 17 Chapter 4. 36 Chapter 5. 41 Chapter 6. 50 Chapter 7. Conclusion 65 3 Chapter 1: Introduction-The Future of Quebec The Quebec separatist movement has been debated for decades and yet no one can seem to come to a conclusion regarding what the future of the province holds for the Quebecers. This thesis aims to look at the reasons for the Quebec separatist movement occurring in the past as well as its steady level of support. Ultimately, there is a split within the recent literature in Quebec, regarding those who believe that independence is off the political agenda and those who think it is back on the agenda. This thesis looks at public opinion polls, and electoral returns, to find that the independence movement is ultimately off the political agenda as of the April 2014 election, but continues to be supported in Quebec public opinion. I will first be analyzing the history of Quebec as well as the theories other social scientists have put forward regarding separatist and nationalist movements in general. Next I will be analyzing the history of Quebec in order to understand why the Quebec separatist movement came about. I will then look at election data from 1995-2012 in order to identify the level of electoral support for separatism as indicated by the vote for the Parti Quebecois (PQ). -

Masterarbeit

MASTERARBEIT Titel der Masterarbeit „Everyday Language Rights as a Reflection of Official Language Policies in Canada and Ukraine (1960s – present)“ Verfasser Oleg Shemetov angestrebter akademischer Grad Master (MA) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 067 805 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Individuelles Masterstudium: Global Studies – a European Perspective Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Kerstin Susanne Jobst, Privatdoz. M.A. MASTERARBEIT / MASTER THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit /Title of the master thesis Everyday Language Rights as a Reflection of Official Language Policies in Canada and Ukraine (1960s – present) Verfasser /Author Oleg Shemetov angestrebter akademischer Grad / acadamic degree aspired Master (MA) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl : A 067 805 Studienrichtung: Individuelles Masterstudium: Global Studies – a European Perspective Betreuer/Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Kerstin Susanne Jobst, Privatdoz. M.A. 2 Table of contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Theoretical Background 2.1. Language rights as human rights 9 2.2. Language policy 12 2.3. Understanding bilingualism 2.3.1. Approaches to understanding the phenomenon of bilingualism 15 2.3.2. Bilingualism as a sociocultural phenomenon of the development of a society 22 3. Issue of Comparability 25 4. Overview of Official Language Policies 4.1. Canadian official bilingualism after the Quiet Revolution in Québec 39 4.2. Development of bilingualism in Ukraine after the Perestroika in the Soviet Union 48 5. Everyday Language Rights in Canada and Ukraine 55 6. Conclusion 70 Bibliography 72 List of Acronyms 85 Appendix 86 Abstract 3 1. Introduction The word distinguishes a man from an animal; language distinguishes one nation from another. Jean-Jacques Rousseau The tie of language is, perhaps, the strongest and most durable that can unite mankind. -

Those Who Came and Those Who Left the Territorial Politics of Migration

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cadmus, EUI Research Repository Department of Political and Social Sciences Those who came and those who left The Territorial Politics of Migration in Scotland and Catalonia Jean-Thomas Arrighi de Casanova Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Florence, February 2012 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE Department of Political and Social Sciences Those who came and those who left The Territorial Politics of Migration in Scotland and Catalonia Jean-Thomas Arrighi de Casanova Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Examining Board: Prof. Rainer Bauböck, EUI (Supervisor) Prof. Michael Keating, EUI (Co-supervisor) Dr Nicola McEwen, University of Edinburgh Prof. Andreas Wimmer, UCLA © 2012, Jean-Thomas Arrighi de Casanova No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author ABSTRACT Whilst minority nationalism and migration have been intensely studied in relative isolation from one another, research examining their mutual relationship is still scarce. This dissertation aims to fill this gap in the literature by exploring how migration politics are being fought over not only across society but also across territory in two well-researched cases of protracted nationalist mobilisation, Catalonia and Scotland. It meets three objectives: First, it introduces a theoretical framework accounting for sub-state elites’ and administrations’ boundary-making strategies in relation to immigrants and emigrants. -

The Roots of French Canadian Nationalism and the Quebec Separatist Movement

Copyright 2013, The Concord Review, Inc., all rights reserved THE ROOTS OF FRENCH CANADIAN NATIONALISM AND THE QUEBEC SEPARATIST MOVEMENT Iris Robbins-Larrivee Abstract Since Canada’s colonial era, relations between its Fran- cophones and its Anglophones have often been fraught with high tension. This tension has for the most part arisen from French discontent with what some deem a history of religious, social, and economic subjugation by the English Canadian majority. At the time of Confederation (1867), the French and the English were of almost-equal population; however, due to English dominance within the political and economic spheres, many settlers were as- similated into the English culture. Over time, the Francophones became isolated in the province of Quebec, creating a densely French mass in the midst of a burgeoning English society—this led to a Francophone passion for a distinct identity and unrelent- ing resistance to English assimilation. The path to separatism was a direct and intuitive one; it allowed French Canadians to assert their cultural identities and divergences from the ways of the Eng- lish majority. A deeper split between French and English values was visible before the country’s industrialization: agriculture, Ca- Iris Robbins-Larrivee is a Senior at the King George Secondary School in Vancouver, British Columbia, where she wrote this as an independent study for Mr. Bruce Russell in the 2012/2013 academic year. 2 Iris Robbins-Larrivee tholicism, and larger families were marked differences in French communities, which emphasized tradition and antimaterialism. These values were at odds with the more individualist, capitalist leanings of English Canada. -

Morality and Nationalism

Morality and Nationalism This book takes a unique approach to explore the moral foundations of nationalism. Drawing on nationalist writings and examining almost 200 years of nationalism in Ireland and Quebec, the author develops a theory of nationalism based on its role in representation. The study of nationalism has tended towards the construction of dichotomies – arguing, for example, that there are political and cultural, or civic and ethnic, versions of the phenomenon. However, as an object of moral scrutiny this bifurcation makes nationalism difficult to work with. The author draws on primary sources to see how nationalists themselves argued for their cause and examines almost two hundred years of nationalism in two well-known cases, Ireland and Quebec. The author identifies which themes, if any, are common across the various forms that nationalism can take and then goes on to develop a theory of nationalism based on its role in representation. This representation-based approach provides a basis for the moral claim of nationalism while at the same time identifying grounds on which this claim can be evaluated and limited. It will be of strong interest to political theorists, especially those working on nationalism, multiculturalism, and minority rights. The special focus in the book on the Irish and Quebec cases also makes it relevant reading for specialists in these fields as well as for other area studies where nationalism is an issue. Catherine Frost is Assistant Professor of Political Theory at McMaster University, Canada. Routledge Innovations in Political Theory 1 A Radical Green Political Theory Alan Carter 2 Rational Woman A feminist critique of dualism Raia Prokhovnik 3 Rethinking State Theory Mark J. -

Comparing Ireland and Quebec: the Case of Feminism Author(S): Linda Connolly Source: the Canadian Journal of Irish Studies , Spring, 2005, Vol

Comparing Ireland and Quebec: The Case of Feminism Author(s): Linda Connolly Source: The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies , Spring, 2005, Vol. 31, No. 1, Irish- Canadian Connections / Les liens irlando-canadiens (Spring, 2005), pp. 76-85 Published by: Canadian Journal of Irish Studies Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25515562 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies This content downloaded from 149.157.1.168 on Thu, 10 Jun 2021 15:07:53 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Linda CONNOLLY Comparing Ireland and Quebec The Case of Feminism1 A notable body of research in Irish-Canadian Studies has emerged in recent decades in key areas, particularly on found in a tendency on the part of both Anglophone and Francophone women's historians to set linguistic cultural boundaries the history of the Irish Diaspora in Canada (for example, to the scope of their work. see several contributions in O'Driscoll and Reynolds, 1988; Akenson, 1996; and Bielenberg, 2000). In recent years, The fact that Ireland is a predominantly English scholars have also become more aware of several interesting speaking nation (regardless of an active Irish-language connections between Ireland and Quebec, in particular. -

Language Education, Canadian Civic Identity and the Identities of Canadians

LANGUAGE EDUCATION, CANADIAN CIVIC IDENTITY AND THE IDENTITIES OF CANADIANS Guide for the development of language education policies in Europe: from linguistic diversity to plurilingual education Reference study Stacy CHURCHILL Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto Language Policy Division DG IV – Directorate of School, Out-of-School and Higher Education Council of Europe, Strasbourg French edition: L’enseignement des langues et l’identité civique canadienne face à la pluralité des identités des Canadiens The opinions expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All correspondence concerning this publication or the reproduction or translation of all or part of the document should be addressed to the Director of School, Out- of-School and Higher Education of the Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex). The reproduction of extracts is authorised, except for commercial purposes, on condition that the source is quoted. © Council of Europe, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .........................................................................................................................5 1. Introduction.........................................................................................................7 2. Linguistic And Cultural Identities In Canada ......................................................8 3. Creating Identity Through Official Bilingualism...............................................11 3.1. Origins of Federal -

Britannica Global Geography System

BRITANNICA GLOBAL GEOGRAPHY SYSTEM BGGS Overview BGGSis the Britannica They use an inquiry approach and are organized Gl obal Ge o gr aphy Syst em, around ten world regions: a modular electronic SouthAsia learning system which SoutheastAsia combinesthe latest peda- gogicalapproach to geogra- ]apan phy leaming with interactive multi-media FormerSoviet Union materials enabling students and teachersto EastAsia immerse themselvesin exciting geographic Australia/ New Zealand/ Pacific investigations. BGGSis made up of the following North Africa / SouthwestAsia components: . Geographiclnquiry into GIobaIlssues Africa-South of the Sahara (GIGI) StudentDataBooks Latin America Teacher'sGuides with OverheadTrans- Europe parenciesin a three-ring binder Laminated Mini-Atlases to accompany EachGIGI module is centeredaround a particular eachmodule question,such as "Why are people in the world a BGGSCD-ROM with User'sManual hungry?" and "Is freedomof movementa basic a 3 BGGSVideodiscs with BarcodeGuides human right?" The lead question is explored in a 3 thematicposters one region of the world, then, in most modules,in a secondregion, before being investigatedin This section of your Teacher'sGuide will exam- North America. ine each component and demonstratehow the components work together to facilitate some very The modulescan be usedin geographyclasses, or exciting geography leaming for you and your selectedmodules can be used in other courses, students! suchas Earth Science,Global Studies,or Econom- ics.Twelve modulesconstitute ample materialfor I. GIGI a full year'sgeography course. Each module is GeographicInquiry into Global Issues(GIGI) accompaniedby setsof laminatedmini-atlases is the foundation of the BGGS.GIGI is a seriesof which students can write on with dry-erase modules developed at the Center for Geographic markers (provided by the teacher),then wipe Education at the University of Colorado at cleanto be re-usedby the next class. -

AFFECTIVE PRACTICES of NATION and NATIONALISM on CANADIAN TELEVISION by MARUSYA BOCIURKIW BFA, Nova Scotia C

I FEEL CANADIAN: AFFECTIVE PRACTICES OF NATION AND NATIONALISM ON CANADIAN TELEVISION by MARUSYA BOCIURKIW B.F.A., Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1982 M.A., York University, 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 2004 © Marusya Bociurkiw 2004 -11 - ABSTRACT In this dissertation, I examine how ideas about the nation are produced via affect, especially Canadian television's role in this discursive construction. I analyze Canadian television as a surface of emergence for nationalist sentiment. Within this commercial medium, U.S. dominance, Quebec separatism, and the immigrant are set in an oppositional relationship to Canadian nationalism. Working together, certain institutions such as the law and the corporation, exercise authority through what I call 'technologies of affect': speech-acts, music, editing. I argue that the instability of Canadian identity is re-stabilized by a hyperbolic affective mode that is frequently produced through consumerism. Delimited within a fairly narrow timeframe (1995 -2002), the dissertation's chronological starting point is the Quebec Referendum of October 1995. It concludes at another site of national and international trauma: media coverage of September 11, 2001 and its aftermath. Moving from traumatic point to traumatic point, this dissertation focuses on moments in televised Canadian history that ruptured, or tried to resolve, the imagined community of nation, and the idea of a national self and national others. I examine television as a marker of an affective Canadian national space, one that promises an idea of 'home'. -

Does the World Need More Canada? the Politics of the Canadian Model in Constitutional Politics and Political Theory

SYMPOSIUM Does the world need more Canada? The politics of the Canadian model in constitutional politics and political theory Sujit Choudhry * Political theorists have long considered the question of how constitutional design can respond to the demands of minority nationalism. In this context, Canada has attained considerable prominence as a model, even though the notion of the model came to prominence during the Canadian constitutional crisis of the 1990s, when Quebec nearly seceded. In part, the much-touted Canadian exemplar may be viewed as an intervention by Canadian political theorists in domestic constitutional debates as a way of supporting national unity. However, the Canadian constitutional crisis also points to the limits of a legal approach to the accommodation of minority nationalism. On the one hand, most constitutions contain a process for constitutional amendment, which conceivably might bring about changes suffi cient to satisfy the minority nation. On the other, the rules for constitutional amendment may encounter profound diffi culties in constituting and regulating moments of constitutive constitutional politics, since it is precisely at those moments that the concept of the political community, which those rules refl ect, is placed at issue by the minority nation. 1. Introduction: Brian Barry versus Will Kymlicka In the past two decades, numerous political theorists have taken up the ques- tion of how constitutional design should respond to ethnic, national, and lin- guistic division. Just as important as that question is the way in which these theorists have responded to it. Some, rather than deriving constitutional strate- gies and models from abstract principles of political morality, have turned to real-life examples to buttress their proposed solutions. -

Dominant Ethnicity and Dominant Nationhood: Empirical and Normative Aspects Introduction Current Scholarship Pertaining to Ethn

Dominant Ethnicity and Dominant Nationhood: Empirical and Normative Aspects Introduction Current scholarship pertaining to ethnicity and nationalism ploughs three main furrows: state nationalism, minority nationalism and minority ethnicity. To this list, one may add the literature on migration, which is linked to minority ethnicity; citizenship studies, which examines the interplay between state nationalism and minority ethnicity; and normative political theory, which concerns itself with the interplay between state nations, minority nations, and minority ethnies. All three literatures therefore neglect the increasingly important phenomenon of dominant ethnicity. (Kaufmann 2004a) The chapter begins by locating dominant ethnicity in the aforementioned literature. It probes the vicissitudes of dominant ethnicity in the developing and developed worlds. It registers the shift from dominant minority to dominant majority control in the developing world, while in the West, it finds increasing demographic and cultural pressure on dominant ethnic majorities. I next consider this volume's chief problematic of dominant nationhood. Here the paper introduces an optical metaphor of referent, lenses and symbolic resources which can help us better unpack the complexity of dominant nationhood. The Canadian case is treated as an instance of 'missionary' nationalism: a competing nationalism to Quebec's rather than the post- national alternative it claims to be. Finally the chapter examines the normative questions thrown up by dominant groups and the implications of dominant ethnicity and nationhood for federalism. Dominant Ethnicity What then, is dominant ethnicity? To answer this question, we need to be specific about our terminology. Since 1980, great strides have been made toward differentiating the concepts of state, nation, and ethnic group, and sketching the linkages between such phenomena.1 States place the emphasis on the instruments of coercion, government and boundary demarcation within a territory. -

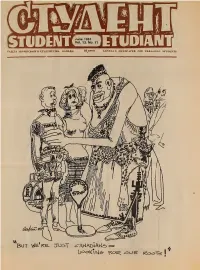

June 1981 I Suspect Intentions of the Sorry, No Subscription Box This Issue

SO cenls CANADA'S NEWSPAPER FOR UKRAINIAN STUDENTS W'a> 1. --.," .0^ P's and B's meef / Ottawa Dana Boyko National Unity in the 80s The Ukrainian Professional ethnic origin, are guaranteed. A argued that a provision for of Rights is a good document for Ukrainians, the Ukrainian and Business Federation Charter of Rights, therefore, minority language bilingual with regard to individual rights, Canadian community must take (UCPBF) held its biennial con- would aid in promoting mul- education including languages but terrible with respect to an active stance in the cause of vention in Ottawa's Skyline ticulturalism in Canada. other than English or French, group rights. Consequently, human rights for other ethnic Hotel over the Victoria Day In addition, Tarnopolsky where viable, should be en- "the Ukrainian community as a minorities in Canada. weekend. Hosted by the Ottawa argued that Ukrainians should trenched in the constitution. group should be against the Regarding the question of Ukrainian Professional and welcome section 23 of the Roman Herchuk from Van- whole exercise." guarantees for ethnocultural Business Association, the con- proposed constitution couver spoke about the human Walter Kolanitch spoke groups, Tarnopolsky asserted vention consisted of two parts: guaranteeing minority rights' situation in British about the situation in Quebec. that it is much easier to defend Saturday was devoted to a language education rights for Columbia. In essence, Herchuk The Ukrainian community in individual rights than group symposium entitled "National the French, wherever numbers stated, people lack knowledge Montreal consts of 22,000 peo- rights. The courts will not Unity in the 1980's", while the warrant, if the French- about human rights.