Ispd Guidelines/Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ceftazidime for Injection) PHARMACY BULK PACKAGE – NOT for DIRECT INFUSION

PRESCRIBING INFORMATION FORTAZ® (ceftazidime for injection) PHARMACY BULK PACKAGE – NOT FOR DIRECT INFUSION To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of FORTAZ and other antibacterial drugs, FORTAZ should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by bacteria. DESCRIPTION Ceftazidime is a semisynthetic, broad-spectrum, beta-lactam antibacterial drug for parenteral administration. It is the pentahydrate of pyridinium, 1-[[7-[[(2-amino-4 thiazolyl)[(1-carboxy-1-methylethoxy)imino]acetyl]amino]-2-carboxy-8-oxo-5-thia-1 azabicyclo[4.2.0]oct-2-en-3-yl]methyl]-, hydroxide, inner salt, [6R-[6α,7β(Z)]]. It has the following structure: The molecular formula is C22H32N6O12S2, representing a molecular weight of 636.6. FORTAZ is a sterile, dry-powdered mixture of ceftazidime pentahydrate and sodium carbonate. The sodium carbonate at a concentration of 118 mg/g of ceftazidime activity has been admixed to facilitate dissolution. The total sodium content of the mixture is approximately 54 mg (2.3 mEq)/g of ceftazidime activity. The Pharmacy Bulk Package vial contains 709 mg of sodium carbonate. The sodium content is approximately 54 mg (2.3mEq) per gram of ceftazidime. FORTAZ in sterile crystalline form is supplied in Pharmacy Bulk Packages equivalent to 6g of anhydrous ceftazidime. The Pharmacy Bulk Package bottle is a container of sterile preparation for parenteral use that contains many single doses. The contents are intended for use in a pharmacy admixture program and are restricted to the preparation of admixtures for intravenous use. THE PHARMACY BULK PACKAGE IS NOT FOR DIRECT INFUSION, FURTHER DILUTION IS REQUIRED BEFORE USE. -

Activity of Aztreonam in Combination with Ceftazidime-Avibactam Against

Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 99 (2021) 115227 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/diagmicrobio Activity of aztreonam in combination with ceftazidime–avibactam against serine- and metallo-β-lactamase–producing ☆ ☆☆ ★ Pseudomonas aeruginosa , , Michelle Lee a, Taylor Abbey a, Mark Biagi b, Eric Wenzler a,⁎ a College of Pharmacy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA b College of Pharmacy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Rockford, IL, USA article info abstract Article history: Existing data support the combination of aztreonam and ceftazidime–avibactam against serine-β-lactamase Received 29 June 2020 (SBL)– and metallo-β-lactamase (MBL)–producing Enterobacterales, although there is a paucity of data against Received in revised form 15 September 2020 SBL- and MBL-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In this study, 5 SBL- and MBL-producing P. aeruginosa (1 Accepted 19 September 2020 IMP, 4 VIM) were evaluated against aztreonam and ceftazidime–avibactam alone and in combination via broth Available online xxxx microdilution and time-kill analyses. All 5 isolates were nonsusceptible to aztreonam, aztreonam–avibactam, – – Keywords: and ceftazidime avibactam. Combining aztreonam with ceftazidime avibactam at subinhibitory concentrations Metallo-β-lactamase produced synergy and restored bactericidal activity in 4/5 (80%) isolates tested. These results suggest that the VIM combination of aztreonam and ceftazidime–avibactam may be a viable treatment option against SBL- and IMP MBL-producing P. aeruginosa. Aztreonam © 2020 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Ceftazidime–avibactam Synergy 1. Introduction of SBLs and MBLs harbored by P. aeruginosa are fundamentally different than those in Enterobacterales (Alm et al., 2015; Kazmierczak et al., The rapid global dissemination of Ambler class B metallo-β- 2016; Periasamy et al., 2020; Poirel et al., 2000; Watanabe et al., lactamase (MBL) enzymes along with their increasing diversity across 1991). -

Use of Ceftaroline Fosamil in Children: Review of Current Knowledge and Its Application

Infect Dis Ther (2017) 6:57–67 DOI 10.1007/s40121-016-0144-8 REVIEW Use of Ceftaroline Fosamil in Children: Review of Current Knowledge and its Application Juwon Yim . Leah M. Molloy . Jason G. Newland Received: November 10, 2016 / Published online: December 30, 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com ABSTRACT infections, CABP caused by penicillin- and ceftriaxone-resistant S. pneumoniae and Ceftaroline is a novel cephalosporin recently resistant Gram-positive infections that fail approved in children for treatment of acute first-line antimicrobial agents. However, bacterial skin and soft tissue infections and limited data are available on tolerability in community-acquired bacterial pneumonia neonates and infants younger than 2 months (CABP) caused by methicillin-resistant of age, and on pharmacokinetic characteristics Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae in children with chronic medical conditions and other susceptible bacteria. With a favorable and those with invasive, complicated tolerability profile and efficacy proven in infections. In this review, the microbiological pediatric patients and excellent in vitro profile of ceftaroline, its mechanism of action, activity against resistant Gram-positive and and pharmacokinetic profile will be presented. Gram-negative bacteria, ceftaroline may serve Additionally, clinical evidence for use in as a therapeutic option for polymicrobial pediatric patients and proposed place in therapy is discussed. Enhanced content To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/ 1F47F0601BB3F2DD. Keywords: Antibiotic resistance; Ceftaroline J. Yim (&) fosamil; Children; Methicillin-resistant St. John Hospital and Medical Center, Detroit, MI, Staphylococcus aureus; Streptococcus pneumoniae USA e-mail: [email protected] L. -

Global Assessment of the Antimicrobial Activity of Polymyxin B Against 54 731 Clinical Isolates of Gram-Negative Bacilli

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector ORIGINAL ARTICLE 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01351.x Global assessment of the antimicrobial activity of polymyxin B against 54 731 clinical isolates of Gram-negative bacilli: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance programme (2001–2004) A. C. Gales1, R. N. Jones2,3 and H. S. Sader1,2 1Division of Infectious Diseases, Universidade Federal de Sa˜o Paulo, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil, 2JMI Laboratories, North Liberty, IA, USA, and 3Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA ABSTRACT In total, 54 731 Gram-negative bacilli isolated worldwide between 2001 and 2004 from diverse sites of infection were tested for susceptibility to polymyxin B by the broth reference microdilution method, with interpretation of results according to CLSI (formerly NCCLS) guidelines. Polymyxin B showed excellent potency and spectrum against 8705 Pseudomonas aeruginosa and 2621 Acinetobacter spp. isolates (MIC50, £ ⁄ ⁄ 1mg L and MIC90,2mg L for both pathogens). Polymyxin B resistance rates were slightly higher for carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (2.7%) and Acinetobacter spp. (2.8%), or multidrug-resistant (MDR) P. aeruginosa (3.3%) and Acinetobacter spp. (3.2%), when compared with the entire group (1.3% for P. aeruginosa and 2.1% for Acinetobacter spp.). Among P. aeruginosa, polymyxin B resistance rates varied from 2.9% in the Asia-Pacific region to only 1.1% in Europe, Latin America and North America, while polymyxin B resistance rates ranged from 2.7% in Europe to 1.7% in North America and Latin America £ ⁄ % among Acinetobacter spp. -

A Phase I, 3-Part Placebo-Controlled Randomised Trial to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of Aztreonam-Av

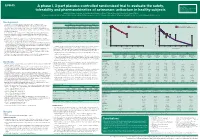

EV0643 Contactinformation: A phase I, 3-part placebo-controlled randomised trial to evaluate the safety, SeamusO’Brien AstraZenecaResearch&Development Macclesfield,Cheshire,UK tolerability and pharmacokinetics of aztreonam-avibactam in healthy subjects [email protected] Timi Edeki1, Diansong Zhou2, Frans van den Berg3, Helen Broadhurst4, William C. Holmes5, Gary Peters3, Maria Sunzel6, Seamus O’Brien4 1AstraZeneca, Wilmington, DE, USA; 2AstraZeneca, Waltham, MA, USA; 3Hammersmith Medicines Research, London, UK; 4AstraZeneca, Macclesfield, UK; 5AstraZeneca, Gaithersburg, MD, USA; 6Contractor at AstraZeneca, Wilmington, DE, USA Background Table 1.Subjects’baselinecharacteristics Figure 1. Geometricmean(A)aztreonamand(B)avibactamconcentration-timeprofilesinPartAfollowingindividualandcombinedadministrationofaztreonam2000mgandavibactam600mgby1-hIVinfusion Part A Part B Part C • Theemergenceandglobaldisseminationofmetallo-β-lactamase(MBL)-producing (A) (B) Enterobacteriaceae,includingNDM-typeandVIM-type,whichareresistanttocarbapenems, Active Placebo Active Placebo Active Placebo 100 Aztreonam 2000 mg alone (n=7) 100 Avibactam 600 mg alone (n=8) representsanurgentthreattohumanhealthforwhichfewtreatmentoptionscurrentlyexist.1, 2 (n=8) (n=4) (n=40) (n=16) (n=18) (n=6) Aztreonam-avibactam 2000-600 mg (n=7) Aztreonam-avibactam 2000-600 mg (n=7) • Aztreonam,amonobactamβ-lactam,isstabletoAmblerclassBMBLsincludingNDM-typeand Mean(SD)age,years 31(7) 34(7) 30(7) 27(5) 49(19) 51(19) VIM-type.However,bacteriathatexpressMBLsfrequentlyco-expressotherclassesofβ-lactamase -

Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Antibiotic Guide

Stanford Health Issue Date: 05/2017 Stanford Antimicrobial Safety and Sustainability Program Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Antibiotic Guide Table 1: Antibiotic selection options for healthcare associated and/or immunocompromised patients • Healthcare associated: intravenous therapy, wound care, or intravenous chemotherapy within the prior 30 days, residence in a nursing home or other long-term care facility, hospitalization in an acute care hospital for two or more days within the prior 90 days, attendance at a hospital or hemodialysis clinic within the prior 30 days • Immunocompromised: Receiving chemotherapy, known systemic cancer not in remission, ANC <500, severe cell-mediated immune deficiency Table 2: Antibiotic selection options for community acquired, immunocompetent patients Table 3: Antibiotic selection options for patients with simple sepsis, community acquired, immunocompetent patients requiring hospitalization. Risk Factors for Select Organisms P. aeruginosa MRSA Invasive Candidiasis VRE (and other resistant GNR) Community acquired: • Known colonization with MDROs • Central venous catheter • Liver transplant • Prior IV antibiotics within 90 day • Recent MRSA infection • Broad-spectrum antibiotics • Known colonization • Known colonization with MDROs • Known MRSA colonization • + 1 of the following risk factors: • Prolonged broad antibacterial • Skin & Skin Structure and/or IV access site: ♦ Parenteral nutrition therapy Hospital acquired: ♦ Purulence ♦ Dialysis • Prolonged profound • Prior IV antibiotics within 90 days ♦ Abscess -

Antimicrobial Surgical Prophylaxis

Antimicrobial Surgical Prophylaxis The antimicrobial surgical prophylaxis protocol establishes evidence-based standards for surgical prophylaxis at The Nebraska Medical Center. The protocol was adapted from the recently published consensus guidelines from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), and the Surgical Infection Society (SIS) and customized to Nebraska Medicine with the input of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in concert with the various surgical groups at the institution. The protocol established here-in will be implemented via standard order sets utilized within One Chart. Routine surgical prophylaxis and current and future surgical order sets are expected to conform to this guidance. Antimicrobial Surgical Prophylaxis Initiation Optimal timing: Within 60 minutes before surgical incision o Exceptions: Fluoroquinolones and vancomycin (within 120 minutes before surgical incision) Successful prophylaxis necessitates that the antimicrobial agent achieve serum and tissue concentrations above the MIC for probable organisms associated with the specific procedure type at the time of incision as well as for the duration of the procedure. Renal Dose Adjustment Guidance The following table can be utilized to determine if adjustments are needed to antimicrobial surgical prophylaxis for both pre-op and post-op dosing. Table 1 Renal Dosage Adjustment Dosing Regimen with Dosing Regimen with CrCl Dosing Regimen with -

Antimicrobial Stewardship Guidance

Antimicrobial Stewardship Guidance Federal Bureau of Prisons Clinical Practice Guidelines March 2013 Clinical guidelines are made available to the public for informational purposes only. The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) does not warrant these guidelines for any other purpose, and assumes no responsibility for any injury or damage resulting from the reliance thereof. Proper medical practice necessitates that all cases are evaluated on an individual basis and that treatment decisions are patient-specific. Consult the BOP Clinical Practice Guidelines Web page to determine the date of the most recent update to this document: http://www.bop.gov/news/medresources.jsp Federal Bureau of Prisons Antimicrobial Stewardship Guidance Clinical Practice Guidelines March 2013 Table of Contents 1. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Antimicrobial Stewardship in the BOP............................................................................................ 4 4. General Guidance for Diagnosis and Identifying Infection ............................................................. 5 Diagnosis of Specific Infections ........................................................................................................ 6 Upper Respiratory Infections (not otherwise specified) .............................................................................. -

Combination Therapy in Complicated Infections Due to S. Aureus

Combination therapy in complicated infections due to S. aureus Alex Soriano ([email protected]) Service of Infectious Diseases Hospital Clínic of Barcelona ESCMIDUniversity of Barcelona eLibrary IDIBAPS © by author Staphylococcal dissemination to different organs 30 min after i.v. Infection (using a real-time Sureward, et al. imaging) Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 1141-51 ESCMID eLibrary © by author Surewaard, et al. Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 1141-51 ESCMID eLibrary Liver, Kupfer cell (purple ) © byS. aureus author(green) Surewaard, et al. Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 1141-51 eradication Large cluster of S. from blood aureus inside of KC. Located in phagolysosomes ESCMID eLibrary © by author Surewaard, et al. Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 1141-51 liver ESCMID eLibrary Vancosomes: vancomycin vancomycin (1h before ©or after by) authorwithin liposomes Surewaard, et al. Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 1141-51 liver ESCMID eLibrary © by author Lehar S, et al. Novel antibody–antibiotic conjugate eliminates intracellular S. aureus. Nature 2015; 527: 1-19 ESCMID eLibrary © by author Lehar S, et al. Novel antibody–antibiotic conjugate eliminates intracellular S. aureus. Nature 2015; 527: 1-19 Animal model of S aureus bacteremia. Treatment started after 24h of the infection ESCMID eLibrary single dose © by author ESCMID CaseeLibrary #1 © by author Medical history: A 27 y-o man, without co-morbidity. -

Synermox 500 Mg/125 Mg Tablets

New Zealand Data Sheet 1. PRODUCT NAME Synermox 500 mg/125 mg Tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Synermox 500 mg/125 mg Tablets: Each film‐coated tablet contains amoxicillin trihydrate equivalent to 500 mg amoxicillin, with potassium clavulanate equivalent to 125 mg clavulanic acid. Excipient(s) with known effect For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Synermox 500 mg/125 mg Tablets: White to off‐white, oval shaped film‐coated tablets, debossed with “RX713” on one side and plain on the other. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1. Therapeutic indications Synermox is indicated in adults and children (see sections 4.2, 4.4 and 5.1) for short term treatment of common bacterial infections such as: Upper Respiratory Tract Infections (including ENT) e.g. Tonsillitis, sinusitis, otitis media. Lower Respiratory Tract Infection e.g. acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, lobar and broncho‐pneumonia. Genito‐urinary Tract Infections e.g. Cystitis, urethritis, pyelonephritis, female genital infections. Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Bone and Joint Infections e.g. Osteomyelitis. Other Infections e.g. septic abortion, puerperal sepsis, intra‐abdominal sepsis, septicaemia, peritonitis, post‐surgical infections. Synermox is indicated for prophylaxis against infection which may be associated with major surgical procedures such as those involving: Gastro‐intestinal tract Pelvic cavity 1 | Page Head and neck Cardiac Renal Joint replacement Biliary tract surgery Infections caused by amoxicillin susceptible organisms are amenable to Synermox treatment due to its amoxicillin content. Mixed infections caused by amoxicillin susceptible organisms in conjunction with Synermox‐susceptible beta‐lactamase‐producing organisms may therefore be treated by Synermox. -

Penicillin Allergy Guidance Document

Penicillin Allergy Guidance Document Key Points Background Careful evaluation of antibiotic allergy and prior tolerance history is essential to providing optimal treatment The true incidence of penicillin hypersensitivity amongst patients in the United States is less than 1% Alterations in antibiotic prescribing due to reported penicillin allergy has been shown to result in higher costs, increased risk of antibiotic resistance, and worse patient outcomes Cross-reactivity between truly penicillin allergic patients and later generation cephalosporins and/or carbapenems is rare Evaluation of Penicillin Allergy Obtain a detailed history of allergic reaction Classify the type and severity of the reaction paying particular attention to any IgE-mediated reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis, hives, angioedema, etc.) (Table 1) Evaluate prior tolerance of beta-lactam antibiotics utilizing patient interview or the electronic medical record Recommendations for Challenging Penicillin Allergic Patients See Figure 1 Follow-Up Document tolerance or intolerance in the patient’s allergy history Consider referring to allergy clinic for skin testing Created July 2017 by Macey Wolfe, PharmD; John Schoen, PharmD, BCPS; Scott Bergman, PharmD, BCPS; Sara May, MD; and Trevor Van Schooneveld, MD, FACP Disclaimer: This resource is intended for non-commercial educational and quality improvement purposes. Outside entities may utilize for these purposes, but must acknowledge the source. The guidance is intended to assist practitioners in managing a clinical situation but is not mandatory. The interprofessional group of authors have made considerable efforts to ensure the information upon which they are based is accurate and up to date. Any treatments have some inherent risk. Recommendations are meant to improve quality of patient care yet should not replace clinical judgment. -

IV Vancomycin Dosing and Monitoring Antibiotic Guidelines Reference Number: 144TD(C)25(H3) Version Number: 6.1 Issue Date: 21/07/2020 Page 1 of 12

Group arrangements: Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust (SRFT) Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust (PAT) IV Vancomycin dosing and monitoring Antibiotic Guidelines Lead Author: Antibiotic Steering Group Additional author(s) Elizabeth Trautt, Consultant Microbiologist; Sue Wei Chong, Antimicrobial Pharmacist Division/ Department:: NCA Diagnostics and Pharmacy Group Applies to: Salford Royal Care Organisation Approving Committee Medicines Management Group Date approved: 02/07/2020 Expiry date: July 2023 Contents Contents 1. Overview (What is this guideline about?) ....................................................................... 2 2. Scope (Where will this document be used?) .................................................................. 2 3. Background (Why is this document important?) ............................................................. 2 4. What is new in this version? ............................................................................................ 3 5. Guideline ......................................................................................................................... 3 5.1 Method of administration ................................................................................................. 3 5.2. Dose calculation .............................................................................................................. 3 5.3. Patients with Renal failure/Kidney disease (CrCl<30ml/min or dialysis) .......................... 4 5.4 Therapeutic drug level monitoring ..................................................................................