Antimicrobial Surgical Prophylaxis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Ceftaroline Fosamil in Children: Review of Current Knowledge and Its Application

Infect Dis Ther (2017) 6:57–67 DOI 10.1007/s40121-016-0144-8 REVIEW Use of Ceftaroline Fosamil in Children: Review of Current Knowledge and its Application Juwon Yim . Leah M. Molloy . Jason G. Newland Received: November 10, 2016 / Published online: December 30, 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com ABSTRACT infections, CABP caused by penicillin- and ceftriaxone-resistant S. pneumoniae and Ceftaroline is a novel cephalosporin recently resistant Gram-positive infections that fail approved in children for treatment of acute first-line antimicrobial agents. However, bacterial skin and soft tissue infections and limited data are available on tolerability in community-acquired bacterial pneumonia neonates and infants younger than 2 months (CABP) caused by methicillin-resistant of age, and on pharmacokinetic characteristics Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae in children with chronic medical conditions and other susceptible bacteria. With a favorable and those with invasive, complicated tolerability profile and efficacy proven in infections. In this review, the microbiological pediatric patients and excellent in vitro profile of ceftaroline, its mechanism of action, activity against resistant Gram-positive and and pharmacokinetic profile will be presented. Gram-negative bacteria, ceftaroline may serve Additionally, clinical evidence for use in as a therapeutic option for polymicrobial pediatric patients and proposed place in therapy is discussed. Enhanced content To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/ 1F47F0601BB3F2DD. Keywords: Antibiotic resistance; Ceftaroline J. Yim (&) fosamil; Children; Methicillin-resistant St. John Hospital and Medical Center, Detroit, MI, Staphylococcus aureus; Streptococcus pneumoniae USA e-mail: [email protected] L. -

Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of Suppression of in Vitro Resistance In

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Pharmacodynamic evaluation of suppression of in vitro resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii strains using polymyxin B‑based combination therapy Nayara Helisandra Fedrigo1, Danielle Rosani Shinohara1, Josmar Mazucheli2, Sheila Alexandra Belini Nishiyama1, Floristher Elaine Carrara‑Marroni3, Frederico Severino Martins4, Peijuan Zhu5, Mingming Yu6, Sherwin Kenneth B. Sy2 & Maria Cristina Bronharo Tognim1* The emergence of polymyxin resistance in Gram‑negative bacteria infections has motivated the use of combination therapy. This study determined the mutant selection window (MSW) of polymyxin B alone and in combination with meropenem and fosfomycin against A. baumannii strains belonging to clonal lineages I and III. To evaluate the inhibition of in vitro drug resistance, we investigate the MSW‑derived pharmacodynamic indices associated with resistance to polymyxin B administrated regimens as monotherapy and combination therapy, such as the percentage of each dosage interval that free plasma concentration was within the MSW (%TMSW) and the percentage of each dosage interval that free plasma concentration exceeded the mutant prevention concentration (%T>MPC). The MSW of polymyxin B varied between 1 and 16 µg/mL for polymyxin B‑susceptible strains. The triple combination of polymyxin B with meropenem and fosfomycin inhibited the polymyxin B‑resistant subpopulation in meropenem‑resistant isolates and polymyxin B plus meropenem as a double combination sufciently inhibited meropenem‑intermediate, and susceptible strains. T>MPC 90% was reached for polymyxin B in these combinations, while %TMSW was 0 against all strains. TMSW for meropenem and fosfomycin were also reduced. Efective antimicrobial combinations signifcantly reduced MSW. The MSW‑derived pharmacodynamic indices can be used for the selection of efective combination regimen to combat the polymyxin B‑resistant strain. -

Cusumano-Et-Al-2017.Pdf

International Journal of Infectious Diseases 63 (2017) 1–6 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Infectious Diseases journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijid Rapidly growing Mycobacterium infections after cosmetic surgery in medical tourists: the Bronx experience and a review of the literature a a b c b Lucas R. Cusumano , Vivy Tran , Aileen Tlamsa , Philip Chung , Robert Grossberg , b b, Gregory Weston , Uzma N. Sarwar * a Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York, USA b Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York, USA c Department of Pharmacy, Nebraska Medicine, Omaha, Nebraska, USA A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Background: Medical tourism is increasingly popular for elective cosmetic surgical procedures. However, Received 10 May 2017 medical tourism has been accompanied by reports of post-surgical infections due to rapidly growing Received in revised form 22 July 2017 mycobacteria (RGM). The authors’ experience working with patients with RGM infections who have Accepted 26 July 2017 returned to the USA after traveling abroad for cosmetic surgical procedures is described here. Corresponding Editor: Eskild Petersen, Methods: Patients who developed RGM infections after undergoing cosmetic surgeries abroad and who ?Aarhus, Denmark presented at the Montefiore Medical Center (Bronx, New York, USA) between August 2015 and June 2016 were identified. A review of patient medical records was performed. Keywords: Results: Four patients who presented with culture-proven RGM infections at the sites of recent cosmetic Mycobacterium abscessus complex procedures were identified. -

General Items

Essential Medicines List (EML) 2019 Application for the inclusion of imipenem/cilastatin, meropenem and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, as reserve second-line drugs for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (complementary lists of anti-tuberculosis drugs for use in adults and children) General items 1. Summary statement of the proposal for inclusion, change or deletion This application concerns the updating of the forthcoming WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (EML) and WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children (EMLc) to include the following medicines: 1) Imipenem/cilastatin (Imp-Cln) to the main list but NOT the children’s list (it is already mentioned on both lists as an option in section 6.2.1 Beta Lactam medicines) 2) Meropenem (Mpm) to both the main and the children’s lists (it is already on the list as treatment for meningitis in section 6.2.1 Beta Lactam medicines) 3) Clavulanic acid to both the main and the children’s lists (it is already listed as amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Amx-Clv), the only commercially available preparation of clavulanic acid, in section 6.2.1 Beta Lactam medicines) This application makes reference to amendments recommended in particular to section 6.2.4 Antituberculosis medicines in the latest editions of both the main EML (20th list) and the EMLc (6th list) released in 2017 (1),(2). On the basis of the most recent Guideline Development Group advising WHO on the revision of its guidelines for the treatment of multidrug- or rifampicin-resistant (MDR/RR-TB)(3), the applicant considers that the three agents concerned be viewed as essential medicines for these forms of TB in countries. -

Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Antibiotic Guide

Stanford Health Issue Date: 05/2017 Stanford Antimicrobial Safety and Sustainability Program Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Antibiotic Guide Table 1: Antibiotic selection options for healthcare associated and/or immunocompromised patients • Healthcare associated: intravenous therapy, wound care, or intravenous chemotherapy within the prior 30 days, residence in a nursing home or other long-term care facility, hospitalization in an acute care hospital for two or more days within the prior 90 days, attendance at a hospital or hemodialysis clinic within the prior 30 days • Immunocompromised: Receiving chemotherapy, known systemic cancer not in remission, ANC <500, severe cell-mediated immune deficiency Table 2: Antibiotic selection options for community acquired, immunocompetent patients Table 3: Antibiotic selection options for patients with simple sepsis, community acquired, immunocompetent patients requiring hospitalization. Risk Factors for Select Organisms P. aeruginosa MRSA Invasive Candidiasis VRE (and other resistant GNR) Community acquired: • Known colonization with MDROs • Central venous catheter • Liver transplant • Prior IV antibiotics within 90 day • Recent MRSA infection • Broad-spectrum antibiotics • Known colonization • Known colonization with MDROs • Known MRSA colonization • + 1 of the following risk factors: • Prolonged broad antibacterial • Skin & Skin Structure and/or IV access site: ♦ Parenteral nutrition therapy Hospital acquired: ♦ Purulence ♦ Dialysis • Prolonged profound • Prior IV antibiotics within 90 days ♦ Abscess -

Antimicrobial Stewardship Guidance

Antimicrobial Stewardship Guidance Federal Bureau of Prisons Clinical Practice Guidelines March 2013 Clinical guidelines are made available to the public for informational purposes only. The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) does not warrant these guidelines for any other purpose, and assumes no responsibility for any injury or damage resulting from the reliance thereof. Proper medical practice necessitates that all cases are evaluated on an individual basis and that treatment decisions are patient-specific. Consult the BOP Clinical Practice Guidelines Web page to determine the date of the most recent update to this document: http://www.bop.gov/news/medresources.jsp Federal Bureau of Prisons Antimicrobial Stewardship Guidance Clinical Practice Guidelines March 2013 Table of Contents 1. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Antimicrobial Stewardship in the BOP............................................................................................ 4 4. General Guidance for Diagnosis and Identifying Infection ............................................................. 5 Diagnosis of Specific Infections ........................................................................................................ 6 Upper Respiratory Infections (not otherwise specified) .............................................................................. -

Susceptibility of Pseudomonas Cepacia Isolated from Children with Cystic Fibrosis1

003 1-3998/86/2011-1174$02.00/0 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 20, No. 1 1, 1986 Copyright O 1986 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Printed in (I.S.A. Decreased Baseline P-Lactamase Production and Inducibility associated with Increased Piperacillin Susceptibility of Pseudomonas cepacia Isolated from Children with Cystic Fibrosis1 CLAUDIO CHIESA,~PAULINE H. LABROZZI, AND STEPHEN C. ARONOFF Department of Pediatrics [C.C., P.H.L., S.C.A.], Case- Western Reserve University School ofMedicine and the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases [S.C.A.], Rainbow Babies and Children's Hospital, Cleveland, Ohio ABSTRACT. The incidence of pulmonary infections in creased since 1978 and is now recovered from 20% of patients children with cystic fibrosis caused by Pseudomonas ce- in some centers (3, 4). pacia, an organism which may possess an inducible 8- Sputum isolates of P. cepacia from children with cystic fibrosis lactamase, has increased since 1978. Seven of 13 sputum are resistant to most P-lactam agents in vitro. In an in vitro study isolates of P. cepacia from children with cystic fibrosis comparing the susceptibilities of 62 consecutive sputum isolates, were classified as inducible by quantitative enzyme produc- concentrations of 64 pg/ml of aztreonam and piperacillin were tion following preincubation with 100, 200, or 400 pg/ml required to inhibit 79 and 87.1 % of the bacterial population, of cefoxitin. The recovery of inducible strains tended to be respectively; 90% of the isolates were inhibited by 8 pg/ml of associated with recent ceftazidime therapy. Susceptibility ceftazidime (5). In vitro, ceftazidime has proven more active to aztreonam, ceftazidime, and piperacillin alone or com- against P. -

Combination Therapy in Complicated Infections Due to S. Aureus

Combination therapy in complicated infections due to S. aureus Alex Soriano ([email protected]) Service of Infectious Diseases Hospital Clínic of Barcelona ESCMIDUniversity of Barcelona eLibrary IDIBAPS © by author Staphylococcal dissemination to different organs 30 min after i.v. Infection (using a real-time Sureward, et al. imaging) Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 1141-51 ESCMID eLibrary © by author Surewaard, et al. Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 1141-51 ESCMID eLibrary Liver, Kupfer cell (purple ) © byS. aureus author(green) Surewaard, et al. Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 1141-51 eradication Large cluster of S. from blood aureus inside of KC. Located in phagolysosomes ESCMID eLibrary © by author Surewaard, et al. Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 1141-51 liver ESCMID eLibrary Vancosomes: vancomycin vancomycin (1h before ©or after by) authorwithin liposomes Surewaard, et al. Identification and treatment of the Staphylococcus aureus reservoir in vivo. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 1141-51 liver ESCMID eLibrary © by author Lehar S, et al. Novel antibody–antibiotic conjugate eliminates intracellular S. aureus. Nature 2015; 527: 1-19 ESCMID eLibrary © by author Lehar S, et al. Novel antibody–antibiotic conjugate eliminates intracellular S. aureus. Nature 2015; 527: 1-19 Animal model of S aureus bacteremia. Treatment started after 24h of the infection ESCMID eLibrary single dose © by author ESCMID CaseeLibrary #1 © by author Medical history: A 27 y-o man, without co-morbidity. -

Australian Public Assessment Refport for Ceftaroline Fosamil (Zinforo)

Australian Public Assessment Report for ceftaroline fosamil Proprietary Product Name: Zinforo Sponsor: AstraZeneca Pty Ltd May 2013 Therapeutic Goods Administration About the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) • The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) is part of the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is responsible for regulating medicines and medical devices. • The TGA administers the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (the Act), applying a risk management approach designed to ensure therapeutic goods supplied in Australia meet acceptable standards of quality, safety and efficacy (performance), when necessary. • The work of the TGA is based on applying scientific and clinical expertise to decision- making, to ensure that the benefits to consumers outweigh any risks associated with the use of medicines and medical devices. • The TGA relies on the public, healthcare professionals and industry to report problems with medicines or medical devices. TGA investigates reports received by it to determine any necessary regulatory action. • To report a problem with a medicine or medical device, please see the information on the TGA website <http://www.tga.gov.au>. About AusPARs • An Australian Public Assessment Record (AusPAR) provides information about the evaluation of a prescription medicine and the considerations that led the TGA to approve or not approve a prescription medicine submission. • AusPARs are prepared and published by the TGA. • An AusPAR is prepared for submissions that relate to new chemical entities, generic medicines, major variations, and extensions of indications. • An AusPAR is a static document, in that it will provide information that relates to a submission at a particular point in time. • A new AusPAR will be developed to reflect changes to indications and/or major variations to a prescription medicine subject to evaluation by the TGA. -

Comparative Ceftaroline Activity Tested Against Staphylococcus Aureus Associated with Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infection from a Tertiary Care Center

RESEARCH PAPER Medical Science Volume : 5 | Issue : 4 | April 2015 | ISSN - 2249-555X Comparative Ceftaroline Activity Tested Against Staphylococcus Aureus Associated with Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infection from A Tertiary Care Center KEYWORDS MRSA, Ceftaroline, vancomycin Dr. Umamageswari S. S. M. Dr. S. Habeeb Mohammed Dr. Shameem Banu Associate Professor- Microbiology Associate Professor-Surgery Professor and HOD- Microbiology Chettinad Hospital & Research Chettinad Hospital & Research Chettinad Hospital & Research Insitute Insitute Insitute Dr. Jayanthi S. Associate Professor- Microbiology Chettinad Hospital & Research Insitute ABSTRACT Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), commonest cause of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection (ABSSSI) has only limited treatment options like vancomycin, Linezolid and teicoplanin. Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibilities to vancomycin is developing nowadays among nosocomial infec- tion. A newest cephalosporin – Ceftaroline has received FDA approval for the treatment of ABSSSI recently has unique activity against MRSA. The aim of the study is to know the prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus in ABSSSI patients and to evaluate the in vitro activity of Ceftaroline, in comparison with other drugs. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration for vancomycin and Ceftaroline were determined by E-test strips. Out of 235 Staphylococcus aureus isolated from ABSSSI patient 32% were MRSA. No vancomycin resistant strain isolated in our study. In vitro, Ceftaroline control the growth of MRSA very effectively at 2mg/ml itself. Ceftaroline is a most welcomed drug in the treatment of MRSA. INTRODUCTION: MATERIALS AND METHODS: Complicated skin and skin structure infection (CSSSIs), now This study was carried out in Chettinad health city and known by the new US FDA as Acute bacterial skin and skin Research Institute, a tertiary care center hospital (Chen- structure infections (ABSSSI) are the most common infec- nai) between April 2013 and May 2014. -

Penicillin Allergy Guidance Document

Penicillin Allergy Guidance Document Key Points Background Careful evaluation of antibiotic allergy and prior tolerance history is essential to providing optimal treatment The true incidence of penicillin hypersensitivity amongst patients in the United States is less than 1% Alterations in antibiotic prescribing due to reported penicillin allergy has been shown to result in higher costs, increased risk of antibiotic resistance, and worse patient outcomes Cross-reactivity between truly penicillin allergic patients and later generation cephalosporins and/or carbapenems is rare Evaluation of Penicillin Allergy Obtain a detailed history of allergic reaction Classify the type and severity of the reaction paying particular attention to any IgE-mediated reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis, hives, angioedema, etc.) (Table 1) Evaluate prior tolerance of beta-lactam antibiotics utilizing patient interview or the electronic medical record Recommendations for Challenging Penicillin Allergic Patients See Figure 1 Follow-Up Document tolerance or intolerance in the patient’s allergy history Consider referring to allergy clinic for skin testing Created July 2017 by Macey Wolfe, PharmD; John Schoen, PharmD, BCPS; Scott Bergman, PharmD, BCPS; Sara May, MD; and Trevor Van Schooneveld, MD, FACP Disclaimer: This resource is intended for non-commercial educational and quality improvement purposes. Outside entities may utilize for these purposes, but must acknowledge the source. The guidance is intended to assist practitioners in managing a clinical situation but is not mandatory. The interprofessional group of authors have made considerable efforts to ensure the information upon which they are based is accurate and up to date. Any treatments have some inherent risk. Recommendations are meant to improve quality of patient care yet should not replace clinical judgment. -

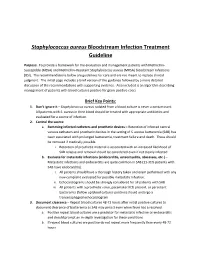

Staphylococcus Aureus Bloodstream Infection Treatment Guideline

Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infection Treatment Guideline Purpose: To provide a framework for the evaluation and management patients with Methicillin- Susceptible (MSSA) and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections (BSI). The recommendations below are guidelines for care and are not meant to replace clinical judgment. The initial page includes a brief version of the guidance followed by a more detailed discussion of the recommendations with supporting evidence. Also included is an algorithm describing management of patients with blood cultures positive for gram-positive cocci. Brief Key Points: 1. Don’t ignore it – Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a blood culture is never a contaminant. All patients with S. aureus in their blood should be treated with appropriate antibiotics and evaluated for a source of infection. 2. Control the source a. Removing infected catheters and prosthetic devices – Retention of infected central venous catheters and prosthetic devices in the setting of S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) has been associated with prolonged bacteremia, treatment failure and death. These should be removed if medically possible. i. Retention of prosthetic material is associated with an increased likelihood of SAB relapse and removal should be considered even if not clearly infected b. Evaluate for metastatic infections (endocarditis, osteomyelitis, abscesses, etc.) – Metastatic infections and endocarditis are quite common in SAB (11-31% patients with SAB have endocarditis). i. All patients should have a thorough history taken and exam performed with any new complaint evaluated for possible metastatic infection. ii. Echocardiograms should be strongly considered for all patients with SAB iii. All patients with a prosthetic valve, pacemaker/ICD present, or persistent bacteremia (follow up blood cultures positive) should undergo a transesophageal echocardiogram 3.