The Value of PFI Hanging in the Balance (Sheet)?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May CARG 2020.Pdf

ISSUE 30 – MAY 2020 ISSUE 30 – MAY ISSUE 29 – FEBRUARY 2020 Promoting positive mental health in teenagers and those who support them through the provision of mental health education, resilience strategies and early intervention What we offer Calm Harm is an Clear Fear is an app to Head Ed is a library stem4 offers mental stem4’s website is app to help young help children & young of mental health health conferences a comprehensive people manage the people manage the educational videos for students, parents, and clinically urge to self-harm symptoms of anxiety for use in schools education & health informed resource professionals www.stem4.org.uk Registered Charity No 1144506 Any individuals depicted in our images are models and used solely for illustrative purposes. We all know of young people, whether employees, family or friends, who are struggling in some way with mental health issues; at ARL, we are so very pleased to support the vital work of stem4: early intervention really can make a difference to young lives. Please help in any way that you can. ADVISER RANKINGS – CORPORATE ADVISERS RANKINGS GUIDE MAY 2020 | Q2 | ISSUE 30 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted The Corporate Advisers Rankings Guide is available to UK subscribers at £180 per in any form or by any means (including photocopying or recording) without the annum for four updated editions, including postage and packaging. A PDF version written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provision is also available at £360 + VAT. of copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Barnard’s Inn, 86 Fetter Lane, London, EC4A To appear in the Rankings Guide or for subscription details, please contact us 1EN. -

Crr 412/2002

HSE Health & Safety Executive A survey of UK approaches to sharing good practice in health and safety risk management Prepared by Risk Solutions for the Health and Safety Executive CONTRACT RESEARCH REPORT 412/2002 HSE Health & Safety Executive A survey of UK approaches to sharing good practice in health and safety risk management E Baker Risk Solutions 1st floor, Central House 14 Upper Woburn Place London, WC1H 0JN United Kingdom The concept of good practice is central to HSE’s approach to regulation of health and safety management. There must therefore be a common understanding of what good practice is and where it can be found. A survey was conducted to explore how industry actually identifies good practice in health and safety management, decides how to adopt it, and how this is communicated with others. The findings are based primarily on a segmentation of the survey results by organisation size, due to homogeneity of the returns along other axes of analysis. A key finding is that there is no common understanding of the term good practice or how this is distinguished from best practice. Regulatory interpretation of good practice is perceived to be inconsistent. Three models were identified: A) Large organisations, primarily in privatised industries, have effective Trade Associations where good practice is developed and guidance disseminated industry-wide. B) Large and medium-sized organisations in competitive industries have ineffective trade associations. They develop good practices in-house and may only share these with their competitors when forced to do so. C) Small organisations have little contact with their competitors. -

![J Jarvis & Sons Ltd V Blue Circle Dartford Estates Ltd [2007]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2296/j-jarvis-sons-ltd-v-blue-circle-dartford-estates-ltd-2007-322296.webp)

J Jarvis & Sons Ltd V Blue Circle Dartford Estates Ltd [2007]

J Jarvis & Sons Ltd v Blue Circle Dartford Estates Ltd [2007] APP.L.R. 05/14 JUDGMENT : MR JUSTICE JACKSON: TCC. 14th May 2007 1. This judgment is in seven parts, namely, Part 1 "Introduction"; Part 2 "The Facts"; Part 3 "The Present Proceedings"; Part 4 "The Law"; Part 5 "The Application for an Injunction"; Part 6 "Jarvis's Challenges to the Interim Award"; and Part 7 "Conclusion". Part 1: Introduction 2. This is an action brought by a main contractor in order to prevent the continuance of an arbitration. The contractor seeks to achieve that result either by means of an injunction or, alternatively, by challenging an Interim Award of the Arbitrator. This litigation has been infused with some urgency because it was launched just fifteen days before the date fixed for the start of arbitration hearing. 3. J Jarvis & Sons Limited is claimant in these proceedings and defendant in the arbitration. Prior to 18th February 1997, the name of this company was J Jarvis & Sons plc. I shall refer to the company as "Jarvis". Jarvis is the subsidiary company of Jarvis plc. Blue Circle Dartford Estates Limited is defendant in these proceedings and claimant in the arbitration. I shall refer to this party as "Blue Circle". Blue Circle is a subsidiary company of Blue Circle Industries plc. The solicitors for the parties will feature occasionally in the narrative. Squire & Co are solicitors for Jarvis. Howrey LLP are solicitors for Blue Circle. 4. I turn now to other companies which will feature in the narrative of events. GEFCO (UK) Limited are forwarding agents. -

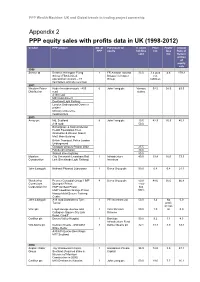

Appendix 2 PPP Equity Sales with Profits Data in UK (1998-2012)

PPP Wealth Machine: UK and Global trends in trading project ownership Appendix 2 PPP equity sales with profits data in UK (1998-2012) Vendor PPP project No. of Purchaser of % share Price Profit/ Annual PPP equity holding £m loss Rate of sold £m Return at time of equity sale 1998 Serco Ltd Defence Helicopter Flying 1 FR Aviation Ltd and 33.0 3.4 plus 4.6 179.3 School (FBS Limited, Bristow Helicopter net operational contract – 47 Group liabilities helicopters and site services) 2001 Western Power Hyder Investments plc - A55 6 John Laing plc Various 92.5 58.5 63.3 Distribution road stakes A130 road M40 road project Dockland Light Railway London Underground Connect project Ministry of Defence headquarters 2003 Amey plc M6, Scotland 8 John Laing plc 19.5 42.9 25.9 45.2 A19 road 50.0 Birmingham & Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust (Erdington & Winson Green) MoD Main Building British Transport Police London Underground Glasgow schools-Project 2002 25.5 Edinburgh schools 30.0 Walsall street lighting 50.0 Mowlem City Greenwich Lewisham Rail 1 Infrastructure 40.0 19.4 16.0 73.3 Construction Link (Docklands Light Railway) Investors John Laing plc National Physical Laboratory 1 Serco Group plc 50.0 0.8 0.4 21.1 Wackenhut Premier Custodial Group: HMP 4 Serco Group plc 50.0 48.6 35.0 66.8 Corrections Dovegate Prison - now Corporation Inc HMP Ashfield Prison has HMP Lowdham Grange Prison 100% Hassockfield Secure Training Centre John Laing plc A19 road Dishforth to Tyne 1 PFI Investors Ltd 50.0 3.4 No 0.0 Tunnel profit or loss Vinci plc Lloyd George -

Safestyle UK Plc Annual Report & Accounts 2019 Safestyle UK Plc

safestyleukplc.co.uk Safestyle UK plc Annual Report & Accounts 2019 Safestyle UK plc Financial Overview Contents Revenue (£m) 2017 158.6 Safestyle UK plc 2018 116.4 -27% Annual Report 2019 2019 126.2 8% The UK’s No.1 for replacement Underlying profit / (loss) before taxation¹ (£m) 2017 15.1 windows and doors³ 2018 (8.7) -158% 01 Welcome page and Financial Overview 2019 (1.5) 83% Strategic Report Reported profit / (loss) before taxation (£m) 06 What we do 2017 13.8 20 Chairman’s Statement 22 CEO’s Statement 2018 (16.3) -218% 24 Financial Review 2019 (3.8) 76% 30 Risk Management 36 Corporate Social Responsibility 38 Our People Net cash² (£m) Governance 2017 11.0 2018 0.3 -98% 46 Board of Directors 48 Audit Committee Report 2019 0.4 71% 50 Directors’ Remuneration Report 58 Directors’ Report Average installed order value (£) 61 Independent Auditor’s Report 2017 3,232 Financials 2018 3,319 3% 68 Consolidated Income Statement 2019 3,337 1% 69 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 70 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 71 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows Average frame price (£) 72 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 2017 608 2018 646 6% 2019 678 5% Frames installed 2017 265,716 2018 184,184 -31% 2019 190,252 3% ¹ See the Financial Review for definition of underlying profit / (loss) before taxation ² See the Financial Review for definition of net cash Annual Report & Accounts 2019 01 ³ Based on Fensa data Safestyle UK plc Highly Recommended All figures from February 2020 Safestyle UK leading the way in customer reviews -

Annual Report and Accounts 2006

ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2006 MAKING TOMORROW A BETTER PLACE Report Section 01 Our Mission, Vision, Values and Strategy Section 02 A Year of Good Progress 02 Financial Highlights 03 Chairman’s Statement Section 03 What We Do 04 At a glance Section 04 Operating and Financial Review 06 Chief Executive’s Review 10 Markets and Outlook Defence/Education/Health Facilities Management and Services/Building Roads and Civil Engineering/Rail Middle East/Canada and the Caribbean 18 Financial Review 22 Corporate Social Responsibility Section 05 A Strong Team 24 Board of Directors Section 06 Accountability 26 Corporate Governance Report 31 Remuneration Report 39 Report of the Directors 42 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities in Respect of the Annual Report and Financial Statements 43 Independent Auditors’ Report to the Members of Carillion plc Section 07 Financial Statements 44 Consolidated Income Statement 45 Consolidated Statement of Recognised Income and Expense 46 Consolidated Balance Sheet 47 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 48 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 82 Company Balance Sheet 83 Notes to the Company Our mission Financial Statements Making tomorrow a better place. Section 08 Further Information Our vision 89 Five Year Review To be the leader in delivering integrated 91 Principal Subsidiary Undertakings, Jointly Controlled Entities and solutions for infrastructure, buildings Jointly Controlled Operations and services. 92 Shareholder Information IBC Advisers For the latest information, including Investor Relations and Sustainability, visit our website any time. www.carillionplc.com Cover – Restoration art The Ikon Gallery, Birmingham is now housed in a former neo-gothic school restored by Carillion to its former architec- tural glory. -

Here Possible

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take you should immediately seek advice from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other independent professional advisor duly authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. If you have sold or otherwise transferred all of your shares in SIG plc, please forward this document and the Form of Proxy as soon as possible to the purchaser or transferee or to the stockbroker, bank or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected, for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. SIG plc (Registered in England No. 998314) Chairman’s Letter to Shareholders and Notice of Annual General Meeting The Annual General Meeting is to be held at the offices of SIG Plc, 10 Eastbourne Terrace, London, W2 6LG on Tuesday 30 June 2020 at 11am The Notice of Annual General Meeting is set out on pages 7 to 9 of this Document. A Form of Proxy for use at the Annual General Meeting is enclosed. SIG plc Notice of Annual General Meeting 2020 01 SIG Notice of Meeting-2020.indd 1 29/05/2020 16:37:24 26982 29 May 2020 4:37 pm Proof 10 SIG plc (Registered in England No. 998314) DIRECTORS: REGISTERED OFFICE A.J. Allner 10 Eastbourne Terrace S.R Francis London K.H.M Kearney-Croft W2 6LG H.C Allum I.B. Duncan G.D.C Kent A.C. Lovell 5 June 2020 Dear Shareholder, ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 2020 NOTICE OF MEETING I am writing to explain in detail the items of business contained in the Notice of Annual General Meeting (the “AGM”) of SIG plc (the “Company”), to be held at 11am on Tuesday 30 June 2020 at the offices of SIG Plc, 10 Eastbourne Terrace, London, W2 6LG. -

Report of the Directors 21

735427 pp21-pp22 6/4/04 12:58 pm Page 21 Alfred McAlpine plc | Annual Report & Accounts 2003 Report of the Directors 21 Report of the Directors The Directors present their Annual Report and the audited accounts for the year ended 31st December, 2003. Principal Activities The Group provides infrastructure, construction and business services, principally in the UK. The operations of the Group are reviewed on pages 6 to 17 of this report. Profits and Dividends The Group profit for the year attributable to shareholders amounted to £22.8m (2002: £14.4m) after tax and goodwill. The Directors recommend the payment of a final dividend of 6.5p per ordinary share which, together with the interim dividend of 4.5p already paid, makes a total of 11p per ordinary share for the financial year. If approved at the Annual General Meeting (‘AGM’) to be held on 20th May, 2004, the final dividend will be paid on 28th May, 2004 to those shareholders on the register at close of business on 7th May, 2004. After provision for these ordinary dividends and dividends of £0.4m paid to preference shareholders, the retained profit of £11.5m (2002: £3.6m) has been transferred to reserves. Post Balance Sheet Event On 6th February, 2004, the Group acquired the entire issued share capital of UK Power Construction Limited for a total cash consideration of £5.2m. Substantial Interests At 22nd March, 2004, the following interests in 3% or more of the Company’s ordinary share capital had been notified to the Company: Number of shares Percentage held % Fidelity International Limited 5,262,986 5.13 Zurich Financial Services 5,105,000 4.98 Aviva plc 4,185,713 4.08 Legal & General Group Plc 3,538,268 3.45 Standard Life Investments 3,159,675 3.08 Directors Present members of the Board are shown on pages 18 and 19. -

Don Dunstan Foundation, University of Adelaide, Australia

Financing Infrastructure in the 21st Century The Long Term Impact of Public Private Partnerships in Britain and Australia Dexter Whitfield Dunstan Paper No 2/2007 Dexter Whitfield Dexter Whitfield founded the European Services Strategy Unit (continuing the work of the Centre for Public Services) in 1973, now based in the Sustainable Cities Research Unit, Northumbria University. He has undertaken extensive research and policy analysis of regional/city economies and public sector provision, jobs and employment strategies, impact assessment and evaluation, marketisation and privatisation, and modernisation and public management. He is the author of New Labour’s Attack on Public Services: How commissioning, choice, competition and contestability threatens public services and the welfare state: Lessons for Europe (Spokesman Books, 2006), Public Services or Corporate Welfare: The Future of the Nation State in the Global Economy (2001), The Welfare State: Privatisation, Deregulation & Commercialisation (1992) and Making it Public: Evidence and Action against Privatisation (1983). He was one of the founding members of Community Action Magazine (1973-1995) and Public Service Action (1983-1998). He has published many articles in journals and delivered papers and advised public bodies and trade unions in Europe, US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Sustainable Cities Research Institute Northumbria University 6 North Street East Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST England Tel +44 (0) 191 227 3500 FAX +44 (0) 191 227 3066 Email: [email protected] Web: www.european-services-strategy.org.uk DUNSTAN PAPERS The Don Dunstan Foundation was established in 1999 with a view to perpetuating the memory of Don Dunstan, former Premier of South Australia and reflecting his life’s work. -

Private Wealth Machine ESSU Research Report No 6

European Services Strategy Unit Research Report No. 6 PPP Wealth Machine __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ UK and Global trends in trading project ownership Dexter Whitfield Financialisation of public infrastructure Market values imposed on public assets Growth of offshore infrastructure funds Secondary market trading UK and Global PPP equity databases PPP Wealth Machine: UK and Global trends in trading project ownership European Services Strategy Unit PPP Equity Database The database can be accessed and downloaded at http://www.european-services-strategy.org.uk/ppp-database/ppp-equity-database/ December 2012 Amended January 2014: Table 4: Annual rate and value of UK PPP equity transactions (1998-2012) Many thanks to Stewart Smyth, Lecturer, Queens University Management Schools, Belfast for advice and comments on the draft and to Jo Chadwick for design of the ESSU database. Dexter Whitfield, Director Adjunct Associate Professor, Australian Workplace Innovation and Social Research Centre, University of Adelaide Mobile +44 (0)777 6370884 Tel. +353 (0)66 7130225 Email: [email protected] Web: www.european-services-strategy.org.uk The European Services Strategy Unit is committed to social justice, through -

LSE CLLN 2005.Pdf

Carillion plc Making tomorrow a better place Carillion plc Birch Street Wolverhampton WV1 4HY United Kingdom T +44 (0)1902 422431 F +44 (0)1902 316165 www.carillionplc.com Making tomorrow a better place Carillion plc Annual Report and Accounts 2005 Annual Report and Accounts 2005 010306 Contents Section What We Do 01 Our Mission, Vision and Strategy 01 A Year of Good Progress 02 Financial Highlights 02 Chairman’s Statement 03 03 Making tomorrow a better place 04 Operating and Financial Review 04 Chief Executive’s Review 08 Markets and Outlook 14 Business Services Health Transport International Regions Financial Review 22 Corporate Social Responsibility 26 A Strong Team 05 Board of Directors 28 Accountability 06 Corporate Governance Report 30 Remuneration Report 35 Report of the Directors 42 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities in Respect of the Annual Report and Financial Statements 44 Independent Auditors’ Report to the Members of Carillion plc 45 Financial Statements 07 Consolidated Income Statement 46 Consolidated Statement of Recognised Income and Expense 47 Consolidated Balance Sheet 48 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 49 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 50 Company Balance Sheet 85 Notes to the Company Financial Statements 86 Further Information 08 Five Year Review 92 Principal Subsidiary Undertakings, Jointly Controlled Entities and Jointly Controlled Operations 94 Shareholder Information 95 Advisers 96 Printed on Zanders Mega Matt – a paper that is manufactured using 50% recycled de-inked fibre and 50% TCF (totally chlorine free) pulp, and is sourced from sustainable forests. The paper is also biodegradable and harmless to the environment. Section 01 Carillion plc What We Do Annual Report and Accounts 2005 01 Our mission Making tomorrow a better place. -

2005 in Fi 2005

ADDRESS LIST 2005 IN FIGURES GRUPO FERROVIAL Million euro Príncipe de Vergara, 135 2005* 2004* 2003 2002 2001 2000 % CAGR% 28002 Madrid 05/04 05/00 FINANCIAL Tel. +34 91 586 25 00 DATA Fax +34 91 586 26 77 ANNUAL REPORT 2005 ANNUAL REPORT Net sales 8,989 7,254 6,026 5,040 4,240 3,598 24% 20% Operating income 871.3 716.8 614.9 485.1 389 271 22% 26% Net income 415.8 528.6 340.6 455.8 218 159 -21% 21% FERROVIAL AGROMÁN FERROVIAL INMOBILIARIA Net income (1) 415.8 289.9 296.2 257.9 Ribera del Loira, 42 López de Hoyos, 35 Parque Empresarial Puerta de las Naciones 28002 Madrid Earnings per share 2.96 3.77 2.43 3.25 1.56 1.14 -21% 21% (1) 28042 Madrid Earnings per share 2.96 2.07 2.11 1.84 Tel. +34 91 586 99 00 Total assets 21,412 15,161 14,552 11,267 10,981 8,821 Fax +34 91 586 25 56 Tel. +34 91 300 85 00 Equity 3,025 2,518 1,754 1,495 1,198 1,050 Fax +34 91 300 88 96 Gross capital expenditure 1,665 389 862 541 430 367 Net debt/(Cash) 272 (139) 591 (303) 287 417 FERROVIAL SERVICIOS Total gross dividend 126.3 115.0 84.2 92.1 55.9 38.6 (1) FERROVIAL INFRAESTRUCTURAS Serrano Galvache, 56 Total gross dividend 85.6 64.5 Plaza Manuel Gómez Moreno, 2 Edificio Madroño - Parque Norte Edificio Alfredo Mahou 28033 Madrid 28020 Madrid OPERATING DATA Tel.