PFI/PPP Buyouts, Bailouts, Terminations and Major Problem Contracts in UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUILDING BLOCKS News from the HCD Group ISSUE 18

BUILDING BLOCKS News from the HCD Group ISSUE 18 IN THIS ISSUE EFFICIENT DESIGN FOR LONDON REGENERATION PIONEERING OXFORD FACILITY 60’S CENTRE UPGRADE FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT DELIVERS FOR SAINSBURY’S NATIONAL ‘BIOLOGICS’ CENTRE www.hcdgroup.co.uk EFFICIENT DESIGN FOR LONDON REGENERATION Acting as Approved Inspector to the scheme, HCD has incorporated complex fire engineering techniques which have allowed the reduction of costly fire resistance to structural steelwork. Following its successful involvement with the adjacent to Hammersmith tube station and Part L 2010. A further innovation will see a first phase of a prime office development in opposite Lyric Square. It will provide 15,330m2 window-wetting sprinkler system utilised to Hammersmith town centre, HCD Building of grade-A office space in an 11 storey building protect the external façades in case of fire. 2 Control is part of the team behind the second plus 560m of cafés, restaurants and additional As well as an efficient envelope, the use of phase of the scheme which is now underway. public spaces. highly effective M&E equipment and roof- Development Securities is pressing ahead with Acting as Approved Inspector to the scheme, mounted solar panels will also contribute to the the £92m project at 12 Hammersmith Grove. HCD has been involved in the evolution of the sustainable credentials of the scheme which is expected to achieve a BREEAM ‘Excellent’ This will complete the developer’s office-led building’s efficient design. Through its proactive rating. Additional features include ‘green’ regeneration in West London following the involvement and wide-ranging expertise sedum roofing to support biodiversity and 2013 completion of its neighbouring, 10,220m2 the company has incorporated complex fire sustainable employee travel will be encouraged development at 10 Hammersmith Grove. -

May CARG 2020.Pdf

ISSUE 30 – MAY 2020 ISSUE 30 – MAY ISSUE 29 – FEBRUARY 2020 Promoting positive mental health in teenagers and those who support them through the provision of mental health education, resilience strategies and early intervention What we offer Calm Harm is an Clear Fear is an app to Head Ed is a library stem4 offers mental stem4’s website is app to help young help children & young of mental health health conferences a comprehensive people manage the people manage the educational videos for students, parents, and clinically urge to self-harm symptoms of anxiety for use in schools education & health informed resource professionals www.stem4.org.uk Registered Charity No 1144506 Any individuals depicted in our images are models and used solely for illustrative purposes. We all know of young people, whether employees, family or friends, who are struggling in some way with mental health issues; at ARL, we are so very pleased to support the vital work of stem4: early intervention really can make a difference to young lives. Please help in any way that you can. ADVISER RANKINGS – CORPORATE ADVISERS RANKINGS GUIDE MAY 2020 | Q2 | ISSUE 30 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted The Corporate Advisers Rankings Guide is available to UK subscribers at £180 per in any form or by any means (including photocopying or recording) without the annum for four updated editions, including postage and packaging. A PDF version written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provision is also available at £360 + VAT. of copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Barnard’s Inn, 86 Fetter Lane, London, EC4A To appear in the Rankings Guide or for subscription details, please contact us 1EN. -

Crr 412/2002

HSE Health & Safety Executive A survey of UK approaches to sharing good practice in health and safety risk management Prepared by Risk Solutions for the Health and Safety Executive CONTRACT RESEARCH REPORT 412/2002 HSE Health & Safety Executive A survey of UK approaches to sharing good practice in health and safety risk management E Baker Risk Solutions 1st floor, Central House 14 Upper Woburn Place London, WC1H 0JN United Kingdom The concept of good practice is central to HSE’s approach to regulation of health and safety management. There must therefore be a common understanding of what good practice is and where it can be found. A survey was conducted to explore how industry actually identifies good practice in health and safety management, decides how to adopt it, and how this is communicated with others. The findings are based primarily on a segmentation of the survey results by organisation size, due to homogeneity of the returns along other axes of analysis. A key finding is that there is no common understanding of the term good practice or how this is distinguished from best practice. Regulatory interpretation of good practice is perceived to be inconsistent. Three models were identified: A) Large organisations, primarily in privatised industries, have effective Trade Associations where good practice is developed and guidance disseminated industry-wide. B) Large and medium-sized organisations in competitive industries have ineffective trade associations. They develop good practices in-house and may only share these with their competitors when forced to do so. C) Small organisations have little contact with their competitors. -

![J Jarvis & Sons Ltd V Blue Circle Dartford Estates Ltd [2007]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2296/j-jarvis-sons-ltd-v-blue-circle-dartford-estates-ltd-2007-322296.webp)

J Jarvis & Sons Ltd V Blue Circle Dartford Estates Ltd [2007]

J Jarvis & Sons Ltd v Blue Circle Dartford Estates Ltd [2007] APP.L.R. 05/14 JUDGMENT : MR JUSTICE JACKSON: TCC. 14th May 2007 1. This judgment is in seven parts, namely, Part 1 "Introduction"; Part 2 "The Facts"; Part 3 "The Present Proceedings"; Part 4 "The Law"; Part 5 "The Application for an Injunction"; Part 6 "Jarvis's Challenges to the Interim Award"; and Part 7 "Conclusion". Part 1: Introduction 2. This is an action brought by a main contractor in order to prevent the continuance of an arbitration. The contractor seeks to achieve that result either by means of an injunction or, alternatively, by challenging an Interim Award of the Arbitrator. This litigation has been infused with some urgency because it was launched just fifteen days before the date fixed for the start of arbitration hearing. 3. J Jarvis & Sons Limited is claimant in these proceedings and defendant in the arbitration. Prior to 18th February 1997, the name of this company was J Jarvis & Sons plc. I shall refer to the company as "Jarvis". Jarvis is the subsidiary company of Jarvis plc. Blue Circle Dartford Estates Limited is defendant in these proceedings and claimant in the arbitration. I shall refer to this party as "Blue Circle". Blue Circle is a subsidiary company of Blue Circle Industries plc. The solicitors for the parties will feature occasionally in the narrative. Squire & Co are solicitors for Jarvis. Howrey LLP are solicitors for Blue Circle. 4. I turn now to other companies which will feature in the narrative of events. GEFCO (UK) Limited are forwarding agents. -

Yorbuild2 East Area Framework – List of Unsuccessful Candidates at ITT Lot 1 0-£250K

YORbuild2 East Area Framework – list of unsuccessful candidates at ITT Lot 1 0-£250k Applicant T H Michaels (Construction) Ltd Evora Construction Limited Britcon Limited George Hurst & Sons Ltd FMe Property Solutions Ltd The Soper Group Ltd Transcore Limited J C Services & Son Ltd Strategic Team Maintenance Co Ltd Stubbs Brothers Building Services Limited Unico Construction Limited Woodhouse-Barry (Construction) Ltd Lot 2 over £250k-£1m Applicant S Voase Builders Limited F Parkinson Ltd Britcon Limited RN Wooler & Co Ltd Illingworth & Gregory Ltd George Hurst & Sons Ltd T H Michaels (Construction) Ltd Transcore Limited PBS Construction Elliott Group Northern Construction Solutions Ltd Woodhouse-Barry (Construction) Ltd Lot 3 over £1m-£4m Applicant Wildgoose Construction ltd Esh Construction Limited Morgan Sindall George Hurst & Sons Ltd Britcon Limited Hall Construction Group Caddick Construction Limited Strategic Team Maintenance Co Ltd F Parkinson Ltd Gentoo Tolent GMI Construction Group PLC United Living Lot 4 over £4m-£10m Applicant Conlon Construction Limited Bowmer & Kirkland Ltd Keepmoat Regeneration Limited Henry Boot Construction Limited Morgan Sindall Hobson and Porter Ltd Robertson Construction Group Ltd Eric Wright Group VINCI Construction UK Limited G F Tomlinson Group Limited Sewell Group Britcon Limited Lot 5 over £10m Applicant Henry Boot Construction Limited Bowmer & Kirkland Ltd John Graham Construction Ltd Morgan Sindall McLaughlin & Harvey (formally Barr Construction Ltd) Eric Wright Group VINCI Construction UK Limited Robertson Construction Group Ltd Caddick Construction Limited J F Finnegan Limited Shepherd Construction Lot 6 New housing up to 10 units Applicant GEDA Construction Lindum Group Limited Woodhouse-Barry (Construction) Ltd Lot 7 New housing over 10 units Applicant Gentoo Tolent Herbert T Forrest Ltd Lindum Group Limited Termrim Construction Strategic Team Maintenance Co Ltd GEDA Construction . -

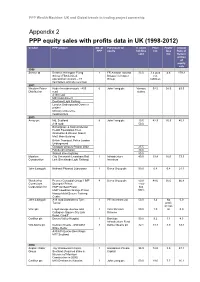

Appendix 2 PPP Equity Sales with Profits Data in UK (1998-2012)

PPP Wealth Machine: UK and Global trends in trading project ownership Appendix 2 PPP equity sales with profits data in UK (1998-2012) Vendor PPP project No. of Purchaser of % share Price Profit/ Annual PPP equity holding £m loss Rate of sold £m Return at time of equity sale 1998 Serco Ltd Defence Helicopter Flying 1 FR Aviation Ltd and 33.0 3.4 plus 4.6 179.3 School (FBS Limited, Bristow Helicopter net operational contract – 47 Group liabilities helicopters and site services) 2001 Western Power Hyder Investments plc - A55 6 John Laing plc Various 92.5 58.5 63.3 Distribution road stakes A130 road M40 road project Dockland Light Railway London Underground Connect project Ministry of Defence headquarters 2003 Amey plc M6, Scotland 8 John Laing plc 19.5 42.9 25.9 45.2 A19 road 50.0 Birmingham & Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust (Erdington & Winson Green) MoD Main Building British Transport Police London Underground Glasgow schools-Project 2002 25.5 Edinburgh schools 30.0 Walsall street lighting 50.0 Mowlem City Greenwich Lewisham Rail 1 Infrastructure 40.0 19.4 16.0 73.3 Construction Link (Docklands Light Railway) Investors John Laing plc National Physical Laboratory 1 Serco Group plc 50.0 0.8 0.4 21.1 Wackenhut Premier Custodial Group: HMP 4 Serco Group plc 50.0 48.6 35.0 66.8 Corrections Dovegate Prison - now Corporation Inc HMP Ashfield Prison has HMP Lowdham Grange Prison 100% Hassockfield Secure Training Centre John Laing plc A19 road Dishforth to Tyne 1 PFI Investors Ltd 50.0 3.4 No 0.0 Tunnel profit or loss Vinci plc Lloyd George -

UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY the Utah State Department of Athletics Is Proud to Recognize the Individuals and Businesses on the Following Pages

AGGIES UNLIMITED ® SUPPORTING STUDENT-ATHLETES AT UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY The Utah State Department of Athletics is proud to recognize the individuals and businesses on the following pages. These Aggie fans have made a financial investment to support USU Athletics and approximately 400 student-athletes. Aggies Unlimited revenues are primarily used to fund student- athlete scholarships, assist with operating expenses and provide academic support. BLUE A SOCIETY Blue A Society members pledge at least $25,000 over a 5-year period or donate $25,000 or more annually to any USU Athletics philanthropic giving funds, including, but not limited to: Aggies Unlimited, Big Blue Scholarship Fund, Merlin Olsen Fund, Wayne Estes Fund, Capital Funds, etc. Kent & Donna Alder Kevin & Melanie Cornett Tom & Renee Grimmett Brady & Jenna Jardine Jim & Carol Laub Nixon & Nixon Al & Michelene Salvo Kevin & Tessa White Boyd Baugh Tracy & Lorie Duckworth John Gutke & Kelly Carmona Avery & Irasema Jeffers Learfield Communications Ray & Shelley Olsen Chris & Doreen Seibert Tom & Patty Willis Brett & Jocelyn Bills Al & Kathie Faccinto Kirk & Sue Ann Hansen Randy & Marcia Jensen Mike & Melanie Lemon Susan Olsen Dennis & Lynn Sessions Matt & Nicole Wiser Scott & Annie Bills Ed & Lisa Fisher Katie & Destrie Hansen Ron & Janet Jibson Jean & Joe Lopour Jed & MerLynn Pitcher Craig & Darcy Smith Bret & Chalisa Wursten Lane & Whitney Blake Bill & Kathy Fletcher John & Heather Hartwell Dan & Carol Johnson Carl & Mary Sue Lundahl Ron & Mike Poindexter Randy & Julie Stockham Fred & Haleen Zweifel James & Heather Bohm Leland & Linda Foster Fred & Sharon Hunsaker Dee Jones JayDee & Machelle Kevin & Stacy Rice Mark & LeAnn Stoddard Mark & Misty Bond Michael & Jo Frankland Chuck & Karen Hyer Nick & Stef Jones Jeff & Jenae Miller Scott & Jodi Richins Mike & Suzie Stones Cache Valley Electric Larry & Jenny Gates Burns & Brenda Israelsen Marty & Betsy Judd Steve & Diane Mothersell Tyler Riggs Lane & Annette Thomas John & Noelle Cockett Doug & Melece Griffin L. -

Safestyle UK Plc Annual Report & Accounts 2019 Safestyle UK Plc

safestyleukplc.co.uk Safestyle UK plc Annual Report & Accounts 2019 Safestyle UK plc Financial Overview Contents Revenue (£m) 2017 158.6 Safestyle UK plc 2018 116.4 -27% Annual Report 2019 2019 126.2 8% The UK’s No.1 for replacement Underlying profit / (loss) before taxation¹ (£m) 2017 15.1 windows and doors³ 2018 (8.7) -158% 01 Welcome page and Financial Overview 2019 (1.5) 83% Strategic Report Reported profit / (loss) before taxation (£m) 06 What we do 2017 13.8 20 Chairman’s Statement 22 CEO’s Statement 2018 (16.3) -218% 24 Financial Review 2019 (3.8) 76% 30 Risk Management 36 Corporate Social Responsibility 38 Our People Net cash² (£m) Governance 2017 11.0 2018 0.3 -98% 46 Board of Directors 48 Audit Committee Report 2019 0.4 71% 50 Directors’ Remuneration Report 58 Directors’ Report Average installed order value (£) 61 Independent Auditor’s Report 2017 3,232 Financials 2018 3,319 3% 68 Consolidated Income Statement 2019 3,337 1% 69 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 70 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 71 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows Average frame price (£) 72 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 2017 608 2018 646 6% 2019 678 5% Frames installed 2017 265,716 2018 184,184 -31% 2019 190,252 3% ¹ See the Financial Review for definition of underlying profit / (loss) before taxation ² See the Financial Review for definition of net cash Annual Report & Accounts 2019 01 ³ Based on Fensa data Safestyle UK plc Highly Recommended All figures from February 2020 Safestyle UK leading the way in customer reviews -

Annual Report and Accounts 2006

ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2006 MAKING TOMORROW A BETTER PLACE Report Section 01 Our Mission, Vision, Values and Strategy Section 02 A Year of Good Progress 02 Financial Highlights 03 Chairman’s Statement Section 03 What We Do 04 At a glance Section 04 Operating and Financial Review 06 Chief Executive’s Review 10 Markets and Outlook Defence/Education/Health Facilities Management and Services/Building Roads and Civil Engineering/Rail Middle East/Canada and the Caribbean 18 Financial Review 22 Corporate Social Responsibility Section 05 A Strong Team 24 Board of Directors Section 06 Accountability 26 Corporate Governance Report 31 Remuneration Report 39 Report of the Directors 42 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities in Respect of the Annual Report and Financial Statements 43 Independent Auditors’ Report to the Members of Carillion plc Section 07 Financial Statements 44 Consolidated Income Statement 45 Consolidated Statement of Recognised Income and Expense 46 Consolidated Balance Sheet 47 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 48 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 82 Company Balance Sheet 83 Notes to the Company Our mission Financial Statements Making tomorrow a better place. Section 08 Further Information Our vision 89 Five Year Review To be the leader in delivering integrated 91 Principal Subsidiary Undertakings, Jointly Controlled Entities and solutions for infrastructure, buildings Jointly Controlled Operations and services. 92 Shareholder Information IBC Advisers For the latest information, including Investor Relations and Sustainability, visit our website any time. www.carillionplc.com Cover – Restoration art The Ikon Gallery, Birmingham is now housed in a former neo-gothic school restored by Carillion to its former architec- tural glory. -

Here Possible

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take you should immediately seek advice from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other independent professional advisor duly authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. If you have sold or otherwise transferred all of your shares in SIG plc, please forward this document and the Form of Proxy as soon as possible to the purchaser or transferee or to the stockbroker, bank or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected, for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. SIG plc (Registered in England No. 998314) Chairman’s Letter to Shareholders and Notice of Annual General Meeting The Annual General Meeting is to be held at the offices of SIG Plc, 10 Eastbourne Terrace, London, W2 6LG on Tuesday 30 June 2020 at 11am The Notice of Annual General Meeting is set out on pages 7 to 9 of this Document. A Form of Proxy for use at the Annual General Meeting is enclosed. SIG plc Notice of Annual General Meeting 2020 01 SIG Notice of Meeting-2020.indd 1 29/05/2020 16:37:24 26982 29 May 2020 4:37 pm Proof 10 SIG plc (Registered in England No. 998314) DIRECTORS: REGISTERED OFFICE A.J. Allner 10 Eastbourne Terrace S.R Francis London K.H.M Kearney-Croft W2 6LG H.C Allum I.B. Duncan G.D.C Kent A.C. Lovell 5 June 2020 Dear Shareholder, ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 2020 NOTICE OF MEETING I am writing to explain in detail the items of business contained in the Notice of Annual General Meeting (the “AGM”) of SIG plc (the “Company”), to be held at 11am on Tuesday 30 June 2020 at the offices of SIG Plc, 10 Eastbourne Terrace, London, W2 6LG. -

Prize Giving Ceremony 2013

Prize Giving Ceremony 2013 Glasgow Caledonian University Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow, G4 0BA T: +44 (0) 141 331 3000 E: [email protected] www.gcu.ac.uk/ebe Glasgow Caledonian University is a registered Scottish charity, number SC021474 Designed and printed by PDS, Glasgow Caledonian University © Glasgow Caledonian University 2013 Congratulations to all prize- Jones Lang LaSalle Sweett Group Welcome to Glasgow Award for Top Honours Level student Award for Top Individual in Interact Competition BSc (Hons) Property Management Valuation BSc (Hons) Quantity Surveying winners and a warm thank Caledonian University Winner: Ben Farrell Winner: Siobhan Morrison you to our sponsors. It is a great privilege to welcome Keppie Design TMC CAD Centre you to Glasgow Caledonian Award for Best Interior Design Student Interior Design 1 Prize University and the Student BA (Hons) Interior Design BA (Hons) Interior Design Awards Event for the School Winner: Darya Fomkin Winner: Katrina Louise Pollock of Engineering and Built Environment. Knight Frank TMC CAD Centre A globally networked University, GCU Award for Top Student in Professional Studies Level 4 Interior Design 2 Prize is committed to providing educational BSc (Hons) Building Surveying BA (Hons) Interior Design opportunity to talented students from Winner: Joe Shaldon Winner: Catherine Rhiannon Stewart a range of backgrounds and delivering research with a practical benefit to society. Our student awards Lambert Smith Hampton TMC CAD Centre events are always a source of pride for staff and students alike Award for Top Professional Placement Student Product Design 1 Best Overall Student in Final Year and celebrate the efforts of each and every member of our BSc (Hons) Property Management Valuation BSc (Hons) International Product Design Welcome to the University community including those who have excelled. -

A Vision of Health Publication

A Vision of Health NHSScotland’s agenda for realising value in the developing healthcare estate A Vision of Health NHSScotland’s agenda for realising value in the developing healthcare estate Foreword Foreword The Better Health, Better Care Action Plan, published in 20071, affirmed the Scottish In this publication we celebrate the vision of some of Scotland’s healthcare leaders Government’s commitment to improving the physical and mental wellbeing of the people including the Chief Medical Officer and healthcare Design Champions and set out the of Scotland through supporting the provision of well designed, sustainable places. The practical measures being put in place to assist Scotland’s NHS Boards in guiding their Action Plan also articulated the Scottish Government’s vision of a mutual National Health projects to successful outcomes. Service, a shift to a new ethos for health in Scotland that sees the Scottish people and the staff of the NHS as partners, or co-owners, in the NHS. Throughout, we feature some current and future-planned projects within NHSScotland which look to provide the quality of environments to which we aspire. These policy changes place health and wellbeing and the over-arching issue of sustainability at the centre of the lives of the people of Scotland as the NHS strives to become more As the Scottish Government’s Purpose and National Performance Framework take ever greater effect in the day-to-day focus for our public services and on improving the Nicola Sturgeon MSP accountable and patient-focused. If we are to deliver on our commitment to create a healthier, wealthier, fairer, safer and stronger Scotland we must ensure that in the context outcomes and quality of life for all of Scotland’s people, it is important that the principles of designing new facilities, NHS Boards deliver not only high quality solutions but also of visionary leadership of those who contributed to this publication are embraced by NHS realise benefits for community development and the wider environment.