Repetitive, Iterative and Habitual Aspectual Affixes in West Greenlandic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aktionsart and Aspect in Qiang

The 2005 International Course and Conference on RRG, Academia Sinica, Taipei, June 26-30 AKTIONSART AND ASPECT IN QIANG Huang Chenglong Institute of Ethnology & Anthropology Chinese Academy of Social Sciences E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Qiang language reflects a basic Aktionsart dichotomy in the classification of stative and active verbs, the form of verbs directly reflects the elements of the lexical decomposition. Generally, State or activity is the basic form of the verb, which becomes an achievement or accomplishment when it takes a directional prefix, and becomes a causative achievement or causative accomplishment when it takes the causative suffix. It shows that grammatical aspect and Aktionsart seem to play much of a systematic role. Semantically, on the one hand, there is a clear-cut boundary between states and activities, but morphologically, however, there is no distinction between them. Both of them take the same marking to encode lexical aspect (Aktionsart), and grammatical aspect does not entirely correspond with lexical aspect. 1.0. Introduction The Ronghong variety of Qiang is spoken in Yadu Township (雅都鄉), Mao County (茂縣), Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture (阿壩藏族羌族自治州), Sichuan Province (四川省), China. It has more than 3,000 speakers. The Ronghong variety of Qiang belongs to the Yadu subdialect (雅都土語) of the Northern dialect of Qiang (羌語北部方言). It is mutually intelligible with other subdialects within the Northern dialect, but mutually unintelligible with other subdialects within the Southern dialect. In this paper we use Aktionsart and lexical decomposition, as developed by Van Valin and LaPolla (1997, Ch. 3 and Ch. 4), to discuss lexical aspect, grammatical aspect and the relationship between them in Qiang. -

Aspectual Forms in Lutsotso

Languages Research Journal in Modern Languages and Literatures https://royalliteglobal.com/languages-and-literatures & Literatures Research Article Section: Literature, Languages and Criticism This article is published Aspectual forms in Lutsotso by Royallite Global, Kenya in the Research Journal in Modern Languages and Hellen Odera¹ & David Barasa² Literatures, Volume 2, Issue ¹-²Department of Languages and Literature Education, 2, 2021 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya Article Information Correspondence: [email protected] Submitted: 15th Jan 2021 Accepted: 30th Mar 2021 Published: 5th April 2021 Abstract This paper analyses the inflectional category of aspect in Additional information is Lutsotso, a dialect of the Oluluhya macro-language. Using available at the end of the descriptive approach, the paper establishes that there are article a number of inflectional morphemes affixed on the verb https://creativecommons. root to express, e.g. person, number, tense, aspect and org/licenses/by/4.0/ mood. Among these affixes, tense and aspect categories interact largely, hence, it is difficult to study one category To read the paper without referring to the other. While tense and aspect are online, please scan this profoundly connected in Lutsotso, this paper only identifies QR code and describes the inflectional form of aspect. Generally, aspect in Lutsotso relates to the grammatical viewpoints such as the perfective, imperfective and iterative forms. This includes the temporal properties of situations and the situation types as well. Aspect just like other grammatical categories such as tense, mood, person, agreement and number are important in understanding the grammar of Lutsotso. Keywords: aspect, Bantu, Lutsotso verb How to Cite: Public Interest Statement Odera, H., & Barasa, D. -

The Semantics of Progressive Aspect: a Thorough Study MOUSUME AKHTER FLORA & S.M

The Semantics of Progressive Aspect: A Thorough Study MOUSUME AKHTER FLORA & S.M. MOHIBUL HASAN Abstract In English grammar, verbs have two important characteristics--tense and aspect. Grammatically tense is marked in two ways: Present and Past. English verbs can have another property called aspect, applicable in both present and past forms of verbs. There are two major types of morphologically marked aspects in English verbs: progressive and perfective. While present and past tenses are morphologically marked by the forms verb+s/es (as in He plays) and verb+d/ed (as in He played) respectively, the morphological representations of progressive and perfective aspects in the tenses are verb+ing (He is/was playing) and verb+d/ed/n/en (He has/had played) respectively. This paper focuses only on one type of aspectual feature of verbs--present progressive. It analyses the use of present progressive in terms of semantics and explains its use in different contexts for durative conclusive and non-conclusive use, for its use in relation to time of reference, and for its use in some special cases. Then it considers the restrictions on the use of progressive aspect in both present and past tenses based on the nature of verbs and duration of time. 1. Introduction ‘Aspect’ has been widely discussed in English grammar with respect to the internal structure of actions, states and events as it revolves around the grammatical category of English verb groups and tenses. Depending on the interpretations of actions, states, and events as a feature of the verbs or as a matter of speaker’s viewpoint, two approaches are available for aspect: ‘Temporal’ and ‘Non-temporal’. -

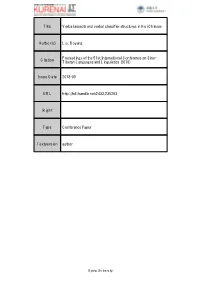

Title Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese

Title Verbal aspects and verbal classifier structures in Hui Chinese Author(s) Liu, Boyang Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235293 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese LIU Boyang (EHESS-CRLAO) CONTENT • PART I: Research Purpose • PART II: The definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 1. An introduction to Hui Chinese – 2. Previous work on VCLs in Mandarin – 3. A provisional definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 4. Lexical aspects indicated by the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP] in Sinitic languages – 5. Relationships between grammatical aspects and the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP- OBJECT] • PART III: Grammatical aspects indicated by special auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures in Hui Chinese – 6. The perfective aspect – 7. The imperfective aspect • PART IV: Conclusion PART I: RESEARCH PURPOSE Research Purpose: • Verbal classifiers (VCLs) have been much less studied from a typological perspective than the category of nominal classifiers (NCLs), and even less in the non-Mandarin branches of Sinitic languages, such as the Hui dialects; • In this study, I will introduce relationships between lexical aspects, grammatical aspects and verbal classifier phrases (VCLPs) in Hui Chinese, analyzing the similarities and differences with Standard Mandarin. • Verbal classifier structures in the Hui dialects display a transitional feature compared with Xiang, Gan and Wu, taking auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures as examples (auto-VCLs derive from verb reduplicants in the verb phrase [VERB- (‘one’)-VERB]): – Auto-VCLs in the verb phrase [VERB-AUTO VCL] can code the perfective or imperfective aspect in different types of complex sentences in Hui Chinese; – More variety of auto-VCL structures is found in Hui Chinese compared with Xiang and Gan dialects. -

A Discourse Analysis of the Periphrastic Imperfect In

A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE PERIPHRASTIC IMPERFECT IN THE GREEK NEW TESTAMENT WRITINGS OF LUKE by CARL E. JOHNSON Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2010 Copyright © by Carl Johnson 2010 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to express my sincere appreciation to each member of my committee whose helpful criticism has made this project possible. I am indebted to Don Burquest for his incredible attention to detail and his invaluable encouragement at certain critical junctures along the way; to my chair Jerold A. Edmondson who challenged me to maintain a linguistic focus and helped me frame this work within the broader linguistic perspective; and to Dr. Chiasson who has helped me write a work that I hope will be accessible to both the linguist and the New Testament Greek scholar. I am also indebted to Robert Longacre who, as an initial member of my committee, provided helpful insight and needed encouragement during the early stages of this work, to Alicia Massingill for graciously proofing numerous editions of this work in a concise and timely manner, and to other members of the Arlington Baptist College family who have provided assistance and encouragement along the way. Finally, I am grateful to my wife, Diana, whose constant love and understanding have made an otherwise impossible task possible. All errors are of course my own, but there would have been far more without the help of many. -

An Introduction to Dena'ina Grammar

AN INTRODUCTION TO DENA’INA GRAMMAR: THE KENAI (OUTER INLET) DIALECT by Alan Boraas, Ph.D. Professor of Anthropology Kenai Peninsula College Based on reference material by: Peter Kalifornsky James Kari, Ph.D. and Joan Tenenbaum, Ph.D. June 30, 2009 revisions May 22, 2010 Page ii Dedication This grammar guide is dedicated to the 20th century children who had their mouth’s washed out with soap or were beaten in the Kenai Territorial School for speaking Dena’ina. And to Peter Kalifornsky, one of those children, who gave his time, knowledge, and friendship so others might learn. Acknowledgement The information in this introductory grammar is based on the sources cited in the “References” section but particularly on James Kari’s draft of Dena’ina Verb Dictionary and Joan Tenenbaum’s 1978 Morphology and Semantics of the Tanaina Verb. Many of the examples are taken directly from these documents but modified to fit the Kenai or Outer Inlet dialect. All of the stem set and verb theme information is from James Kari’s electronic Dena’ina verb dictionary draft. Students should consult the originals for more in-depth descriptions or to resolve difficult constructions. In addition much of the material in this document was initially developed in various language learning documents developed by me, many in collaboration with Peter Kalifornsky or Donita Peter for classes taught at Kenai Peninsula College or the Kenaitze Indian Tribe between 1988 and 2006, and this document represents a recent installment of a progressively more complete grammar. Anyone interested in Dena’ina language and culture owes a huge debt of gratitude to Dr. -

'The System of Tense and Aspect in the Bantik Language'

The System of Tense and Aspect in the Bantik Language UTSUMI Atsuko Meisei University, Tokyo Japan The Bantik language, which belongs to the Sangiric micro-group (cf. Sneddon 1993) within the Philippine group, has two morphologically indicated tense oppositions—the non-past tense and the past tense. In addition, the language includes progressive, habitual, and iterative aspects. This paper aims, first, to present an overview of the tense and aspect systems in the Bantik language. Although Philippine languages are normally described as not having tenses but, rather, as having aspect, a group of Bantik verbs seem to show a tense opposition. Second, it focuses on the classification of Bantik verbs with respect to the meanings they express by their tense forms. In short, stative verbs express a current event by using the non-past tense, while achievement verbs express a future event with the non-past tense. Activity verbs are categorized into two groups; the first group uses the non-past tense to express a current event, while the second group expresses a future event. Abilitative verbs, in contrast to the other verbs, use the non-past form to refer to a past event. 1. Overview of Bantik Morphology concerning tense and aspect 1.1 Overview of tense and aspect in Philippine type languages In much of the literature on the Philippine type languages which are found across the Philippines and from North to Central Sulawesi, verbs are described as having aspect, but not tense. Most of those languages are claimed to have moods as well. For example, Himmelmann (2005:363) shows that the Tagalog verb paradigm has both a perfective/imperfective aspect opposition and a non-realis/realis mood opposition. -

STUDIES in SOUTHERN WAKASHAN (NOOTKAN) GRAMMAR by Matthew Davidson June 2002 a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Grad

STUDIES IN SOUTHERN WAKASHAN (NOOTKAN) GRAMMAR by Matthew Davidson June 2002 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of State University of New York at Buffalo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics iii Acknowledgements I have many people to thank for their contributions to my dissertation. First, I must thank the people of Neah Bay, Washington for their hospitality and generosity during my stay there. The staff of the Makah Cultural and Reseach Center and the Makah Language Program merit special recognition for their unwavering support of my project, so thanks to Janine Bowechop, Yvonne Burkett, Cora Buttram, Keely Parker, Theresa Parker, Maria Pascua, and Melissa Peterson. Of all my friends in Neah Bay, I am most indebted to my primary Makah language consultant, Helma Swan Ward, who spent many patient hours answering questions about Makah and sharing her insights about the language with me. My project has benefited greatly from the labors of my dissertation committee at SUNY Buf- falo, Karin Michelson, Matthew Dryer, and Jean-Pierre Koenig. Their insights concerning both analytic matters and organizational details made the dissertation better than it otherwise would have been. Bill Jacobsen, my outside reader, deserves my gratitude for his meticulous reading of the manuscript on short notice, which resulted in many improvements to the final work. Thanks also to Jay Powell, who facilitated my initial contact with the Makah. I gratefully acknowledge funding for my research from the Jacobs Research Funds and the Mark Diamond Research Fund of the Graduate Student Association of the State University of New York at Buffalo. -

Events in Space

Events in Space Amy Rose Deal University of Massachusetts, Amherst 1. Introduction: space as a verbal category Many languages make use of verbal forms to express spatial relations and distinc- tions. Spatial notions are lexicalized into verb roots, as in come and go; they are expressed by derivational morphology such as Inese˜no Chumash maquti ‘hither and thither’ or Shasta ehee´ ‘downward’ (Mithun 1999: 140-141); and, I will argue, they are expressed by verbal inflectional morphology in Nez Perce. This verbal inflec- tion for space shows a number of parallels with inflection for tense, which it appears immediately below. Like tense, space markers in Nez Perce are a closed-class in- flectional category with a basic locative meaning; they differ in the axis along which their locative meaning is computed. The syntax and semantics of space inflection raises the question of just how tight the liaison is between verbal categories and temporal specification. I argue that in view of the presence of space inflection in languages like Nez Perce, tense marking is best captured as a device for narrowing the temporal coordinates of a spatiotemporally located sentence topic. 2. The grammar of space inflection There are two morphemes in the category of space inflection, cislocative (proximal) -m and translocative (distal) -ki. Space inflection is optional; verbs without space inflection can describe situations that take place anywhere in space.1 I will refer to the members of the space inflection category as space markers. Space inflection is a suffixal category in Nez Perce, and squarely a part of the “inflectional suffix complex” or tense-aspect-mood complex of suffixes. -

Aorist and Pseudo-Aorist for Svan Atelic Verbs — K. Tuite 0. Introduction. the Kartvelian Or South Caucasian Family Comprises

Aorist and pseudo-aorist for Svan atelic verbs — K. Tuite 0. Introduction. The Kartvelian or South Caucasian family comprises three languages: Georgian, which has been attested in documents going back to the 5th century, Zan (or Laz-Mingrelian) and Svan. In the case of Zan and Svan, there is almost no documentation going back beyond the mid-19th century. There is a concensus among experts that Svan is the outlying member of the family, whose family tree would be as in this diagram: COMMON KARTVELIAN COMMON GEORGIAN-ZAN PREHISTORIC SVAN GEORGIAN ZAN MINGRELIAN LAZ Upper Bal Lower Bal Lashx Lent’ex (Upper Svan dialects) (Lower Svan dialects) In this paper I will look at one segment of the formal system in Svan — in particular, in the more conservative Upper Svan dialects — for coding aspect. In this introductory section I will go over the system of what Kartvelologists term “screeves” (sets of verb forms differing only in person and number), and then the classification of verbs by lexical aspect with which the morphological facts will be compared. 0.1. Screeves and series. In the morphology of verbs in each of the Kartvelian languages, one of the fundamental distinctions is between verb forms derived from the SERIES I OR “PRESENT-SERIES” stem, and forms derived from the SERIES II OR “AORIST-SERIES” stem. We will not go into all of the formal differences between these two stems for the various groups of verbs in each language, save to note that for most verbs the Series I stem contains a suffix (the “series marker” or “present/future stem formant”) which does not appear in Series II forms. -

Aspect in Chechen Zarina Molochieva University of California, Berkeley Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig

Aspect in Chechen Zarina Molochieva University of California, Berkeley Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig Introduction1,2 This paper deals with the aspectual system in Chechen (Nakh, Nakh-Daghestanian or Northeast Caucasian). Chechen has a very complex aspectual system. First, there are morphologically marked perfective and imperfective oppositions. There are also a habitual aspect and two kinds of progressive aspect: durative progressive and focalized progressive, which can in turn combine with other aspectual oppositions. The habitual can be combined with the focalized progressive and durative progressive. In addition, there is a full-fledged iterative aspect, which can be marked as perfective, imperfective, habitual, and progressive, as well. In order to better explain the semantics of each aspect type I analyze them separately. I argue that Chechen possesses an equipollent aspectual system. I also discuss the relationship between the imperfective and progressive aspect, and how they differ, and the semantic distinctions between iterative and habitual aspects in Chechen. 1. Marking In Chechen, aspect is marked by stem alternation (vowel ablaut in the productive conjugations) (Beerle 1988, Handel 2003, Nichols & Vagapov 2004). Depending on the underlying stem vowel, Chechen verbs can overtly distinguish up to seven stem forms. Some examples showing the different stem variations are illustrated in Table 1. Some verbs do not distinguish between perfective 1 and perfective 2 (for the witnessed tenses) stems (e.g. -

A'ingae (Cofán/Kofán) Operators

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 328–355 Research Article Kees Hengeveld*, Rafael Fischer A’ingae (Cofán/Kofán) Operators https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0018 Received May 9, 2018; accepted July 16, 2018 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to show how the TAME system of A'ingae, a language isolate spoken in Colombia and Ecuador, can be captured within the theoretical framework of Functional Discourse Grammar. An important prediction in this theory is that the surface order of TAME expressions reflects the scope relations between them in their underlying representation. An initial analysis reveals that, with three exceptions, the A'ingae TAME system confirms this prediction. Closer inspection of the three exceptions, which concern basic illocution, evidentiality, and quantificational aspect, then reveals that on the one hand, the theoretical model has to be adapted, while on the other hand some of the A'ingae facts allow for an alternative interpretation. Keywords: A'ingae, TAME-systems, Functional Discourse Grammar, quantificational aspect, reportativity, basic illocution 1 Introduction This paper studies the expression of aspect, tense, mood, evidentiality and related categories in A’ingae. The description is guided by the theoretical framework of Functional Discourse Grammar, especially by the hierarchical, layered approach to operators taken in this approach. The idea that operators are in scopal relationships leads to predictions concerning the combinability and ordering of operators that will turn out to be relevant to the A’ingae system as well. In what follows we will first, in Section 2, briefly introduce the A’ingae language. In Section 3 we then present the operator inventory of A’ingae in descriptive terms.