Aspectuality in Hindi: the Two Pairs of Aspects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi Smriti Singh1, Om P. Damani2, Vaijayanthi M. Sarma2 (1) Insideview Technologies (India) Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad (2) Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai, India [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT We present algorithms for identifying Hindi Noun Groups and Verb Groups in a given text by using morphotactical constraints and sequencing that apply to the constituents of these groups. We provide a detailed repertoire of the grammatical categories and their markers and an account of their arrangement. The main motivation behind this work on word group identification is to improve the Hindi POS Tagger’s performance by including strictly contextual rules. Our experiments show that the introduction of group identification rules results in improved accuracy of the tagger and in the resolution of several POS ambiguities. The analysis and implementation methods discussed here can be applied straightforwardly to other Indian languages. The linguistic features exploited here are drawn from a range of well-understood grammatical features and are not peculiar to Hindi alone. KEYWORDS : POS tagging, chunking, noun group, verb group. Proceedings of COLING 2012: Technical Papers, pages 2491–2506, COLING 2012, Mumbai, December 2012. 2491 1 Introduction Chunking (local word grouping) is often employed to reduce the computational effort at the level of parsing by assigning partial structure to a sentence. A typical chunk, as defined by Abney (1994:257) consists of a single content word surrounded by a constellation of function words, matching a fixed template. Chunks, in computational terms are considered the truncated versions of typical phrase-structure grammar phrases that do not include arguments or adjuncts (Grover and Tobin 2006). -

Tigre and the Case of Internal Reduplication*

San Diego Linguistic Papers 1 (2003) 109-128 TRIPLE TAKE: TIGRE AND THE CASE OF * INTERNAL REDUPLICATION Sharon Rose University of California, San Diego _______________________________________________________________________ Ethiopian Semitic languages all have some form of internal reduplication. The characteristics of Tigre reduplication are described here, and are shown to diverge from the other languages in two main respects: i) the meaning and ii) the ability to incur multiple reduplication of the reduplicative syllable. The formation of internal reduplication is accomplished via infixation plus addditional templatic shape requirements which override many properties of the regular verb stem. Further constraints on realization of the full reduplicative syllable outweigh restrictions on multiple repetition of consonants, particularly gutturals. _______________________________________________________________________ 1 Introduction Ethiopian Semitic languages have a form of internal reduplication, often termed the ‘frequentative’, which is formed by means of an infixed ‘reduplicative syllable’ consisting of reduplication of the penultimate root consonant and a vowel, usually [a]: ex. Tigrinya s«bab«r« ‘break in pieces’ corresponding to the verb s«b«r« ‘break’.1 Leslau (1939) describes the semantic value of the frequentative as reiterative, intensive, augmentative or attenuative, to which one could add distributive and diminutive. This paper focuses on several aspects of internal reduplication in Tigre, the northernmost Ethio-Semitic language. I present new data demonstrating that not only does Tigre allow internal reduplication with a wide variety of verbs, but it differs notably from other Ethiopian Semitic languages in two important respects: (1) a. the meaning of the internal reduplication is normally ‘diminutive’ or represents elapsed time between action; in the other languages it is usually intensive. -

Diachrony of Ergative Future

• THE EVOLUTION OF THE TENSE-ASPECT SYSTEM IN HINDI/URDU: THE STATUS OF THE ERGATIVE ALGNMENT Annie Montaut INALCO, Paris Proceedings of the LFG06 Conference Universität Konstanz Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2006 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ Abstract The paper deals with the diachrony of the past and perfect system in Indo-Aryan with special reference to Hindi/Urdu. Starting from the acknowledgement of ergativity as a typologically atypical feature among the family of Indo-European languages and as specific to the Western group of Indo-Aryan dialects, I first show that such an evolution has been central to the Romance languages too and that non ergative Indo-Aryan languages have not ignored the structure but at a certain point went further along the same historical logic as have Roman languages. I will then propose an analysis of the structure as a predication of localization similar to other stative predications (mainly with “dative” subjects) in Indo-Aryan, supporting this claim by an attempt of etymologic inquiry into the markers for “ergative” case in Indo- Aryan. Introduction When George Grierson, in the full rise of language classification at the turn of the last century, 1 classified the languages of India, he defined for Indo-Aryan an inner circle supposedly closer to the original Aryan stock, characterized by the lack of conjugation in the past. This inner circle included Hindi/Urdu and Eastern Panjabi, which indeed exhibit no personal endings in the definite past, but only gender-number agreement, therefore pertaining more to the adjectival/nominal class for their morphology (calâ, go-MSG “went”, kiyâ, do- MSG “did”, bola, speak-MSG “spoke”). -

Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds

Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds Their Diachronic Development Within the Greek Compound System Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS ISBN 978-3-11-041576-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041582-7 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041586-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Umschlagabbildung: Paul Klee: Einst dem Grau der Nacht enttaucht …, 1918, 17. Aquarell, Feder und Bleistit auf Papier auf Karton. 22,6 x 15,8 cm. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern. Typesetting: Dr. Rainer Ostermann, München Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS This book is for Arturo, who has waited so long. Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Preface and Acknowledgements Preface and Acknowledgements I have always been ὀψιανθής, a ‘late-bloomer’, and this book is a testament to it. -

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615 Richards, Ivor Armstrong 1936 The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rockwell, Patricia 2007 Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycho- linguistic Research 36: 361−369. Rosenblum, Doron 5. March 2004 Smart he is not. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/smart-he-is-not- 1.115908. Searle, John 1979 Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seddiq, Mirriam N. A. Why I don’t want to talk to you. http://notguiltynoway.com/2004/09/why-i-dont-want- to-talk-to-you.html. Singh, Onkar 17. December 2002 Parliament attack convicts fight in court. http://www.rediff.com/news/ 2002/dec/17parl2.htm [Accessed 24 July 2013]. Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Voegele, Jason N. A. http://www.jvoegele.com/literarysf/cyberpunk.html Voyer, Daniel and Cheryl Techentin 2010 Subjective acoustic features of sarcasm: Lower, slower, and more. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 1−16. Ward, Gregory 1983 A pragmatic analysis of epitomization. Papers in Linguistics 17: 145−161. Ward, Gregory and Betty J. Birner 2006 Information structure. In: B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.), Handbook of English Lin- guistics, 291−317. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Rachel Giora, Tel Aviv, (Israel) 30. Tense Aspect Mood 1. Introduction 2. Metaphor: EVENTS ARE (PHYSICAL) OBJECTS 3. Polysemy, construal, profiling, and coercion 4. Interactions of tense, aspect, and mood 5. Conclusion 6. References 1. Introduction In the framework of cognitive linguistics we approach the grammatical categories of tense, aspect, and mood from the perspective of general cognitive strategies. -

Toward a Definitive Grammar of Bengali - a Practical Study and Critique of Research on Selected Grammatical Structures

TOWARD A DEFINITIVE GRAMMAR OF BENGALI - A PRACTICAL STUDY AND CRITIQUE OF RESEARCH ON SELECTED GRAMMATICAL STRUCTURES HANNE-RUTH THOMPSON Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD SOUTH ASIA DEPARTMENT SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES LONDON O c t o b e r ZOO Laf ProQuest Number: 10672939 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672939 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis is a contribution to a deeper understanding of selected Bengali grammatical structures as far as their syntactic and semantic properties are concerned. It questions traditional interpretations and takes a practical approach in the detailed investigation of actual language use. My methodology is based on the belief that clarity and inquisitiveness should take precedence over alliance to particular grammar theories and that there is still much to discover about the way the Bengali language works. Chapter 1 This chapter on non-finite verb forms discusses the occurrences and functions of Bengali non-finite verb forms and concentrates particularly on the overlap of infinitives and verbal nouns, the distinguishing features between infinitives and present participles, the semantic properties of verbal adjectives and the syntactic restrictions of perfective participles. -

Aspectual Forms in Lutsotso

Languages Research Journal in Modern Languages and Literatures https://royalliteglobal.com/languages-and-literatures & Literatures Research Article Section: Literature, Languages and Criticism This article is published Aspectual forms in Lutsotso by Royallite Global, Kenya in the Research Journal in Modern Languages and Hellen Odera¹ & David Barasa² Literatures, Volume 2, Issue ¹-²Department of Languages and Literature Education, 2, 2021 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya Article Information Correspondence: [email protected] Submitted: 15th Jan 2021 Accepted: 30th Mar 2021 Published: 5th April 2021 Abstract This paper analyses the inflectional category of aspect in Additional information is Lutsotso, a dialect of the Oluluhya macro-language. Using available at the end of the descriptive approach, the paper establishes that there are article a number of inflectional morphemes affixed on the verb https://creativecommons. root to express, e.g. person, number, tense, aspect and org/licenses/by/4.0/ mood. Among these affixes, tense and aspect categories interact largely, hence, it is difficult to study one category To read the paper without referring to the other. While tense and aspect are online, please scan this profoundly connected in Lutsotso, this paper only identifies QR code and describes the inflectional form of aspect. Generally, aspect in Lutsotso relates to the grammatical viewpoints such as the perfective, imperfective and iterative forms. This includes the temporal properties of situations and the situation types as well. Aspect just like other grammatical categories such as tense, mood, person, agreement and number are important in understanding the grammar of Lutsotso. Keywords: aspect, Bantu, Lutsotso verb How to Cite: Public Interest Statement Odera, H., & Barasa, D. -

Ing Forms: the Analysis of Their Meaning and Structure on the Basis of Lithuanian Translation of the Selected Novels by Jane Austen

LITHUANIAN UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF PHILOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHILOLOGY Aneta Narkevič -ING FORMS: THE ANALYSIS OF THEIR MEANING AND STRUCTURE ON THE BASIS OF LITHUANIAN TRANSLATION OF THE SELECTED NOVELS BY JANE AUSTEN MA THESIS Academic advisor: Dr. Judita Giparaitė Vilnius, 2016 LIETUVOS EDUKOLOGIJOS UNIVERSITETAS FILOLOGIJOS FAKULTETAS ANGLŲ FILOLOGIJOS KATEDRA -ING FORMOS: REIKŠMIŲ IR STRUKTŪROS ANALIZĖ BEI VERTIMO STRATEGIJOS JANE AUSTEN ROMANUOSE Magistro darbas Magistro darbo autorė Aneta Narkevič Patvirtinu, kad darbas atliktas savarakiškai, naudojant tik darbe nurodytu šaltinius _______________________________ Vadovas dr. Judita Giparaitė ______________________________ CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 10 1. ANALYSIS OF –ING FORMS ............................................................................................ 13 1.1.Traditional view of -ing forms ........................................................................................ 13 1.1.1. -Ing forms: participles or gerunds? ......................................................................... 14 1.1.2. Nominal and verbal properties of ing forms ........................................................... 14 1.1.3. Syntax of –ing forms .............................................................................................. -

Development and Analysis of Verb Frame Lexicon for Hindi

Linguistics and Literature Studies 5(1): 1-22, 2017 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2017.050101 Development and Analysis of Verb Frame Lexicon for Hindi Rafiya Begum*, Dipti Misra Sharma Language Technology and Research Center, India Copyright©2017 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract A verb frame (VF) captures various syntactic relatively flexible word order [2,3]. There is a debate in the distributions where a verb can be expected to occur in a literature whether the notions subject and object can at all be language. The argument structure of Hindi verbs (for various defined for ILs [4]. Behavioral properties are the only criteria senses) is captured in the verb frames (VFs). The Hindi verbs based on which one can confidently identify grammatical were also classified based on their argument structure. The functions in Hindi [5]; Marking semantic properties such as main objective of this work is to create a linguistic resource thematic roles as dependency relations is problematic too. of Hindi verb frames which would: (i)Help the annotators in Thematic roles are abstract notions and require higher the annotation of the dependency relations for various verbs; semantic features which are difficult to formulate and to (ii)Prove to be useful in parsing and for other Natural extract. Therefore, a grammatical model which can account Language Processing (NLP) applications; (iii)Be helpful for for most of the linguistic phenomena in ILs and would also scholars interested in the linguistic study of the Hindi verbs. -

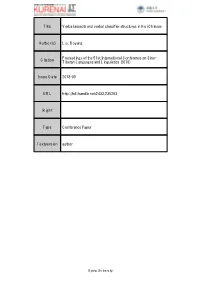

Title Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese

Title Verbal aspects and verbal classifier structures in Hui Chinese Author(s) Liu, Boyang Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235293 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese LIU Boyang (EHESS-CRLAO) CONTENT • PART I: Research Purpose • PART II: The definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 1. An introduction to Hui Chinese – 2. Previous work on VCLs in Mandarin – 3. A provisional definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 4. Lexical aspects indicated by the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP] in Sinitic languages – 5. Relationships between grammatical aspects and the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP- OBJECT] • PART III: Grammatical aspects indicated by special auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures in Hui Chinese – 6. The perfective aspect – 7. The imperfective aspect • PART IV: Conclusion PART I: RESEARCH PURPOSE Research Purpose: • Verbal classifiers (VCLs) have been much less studied from a typological perspective than the category of nominal classifiers (NCLs), and even less in the non-Mandarin branches of Sinitic languages, such as the Hui dialects; • In this study, I will introduce relationships between lexical aspects, grammatical aspects and verbal classifier phrases (VCLPs) in Hui Chinese, analyzing the similarities and differences with Standard Mandarin. • Verbal classifier structures in the Hui dialects display a transitional feature compared with Xiang, Gan and Wu, taking auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures as examples (auto-VCLs derive from verb reduplicants in the verb phrase [VERB- (‘one’)-VERB]): – Auto-VCLs in the verb phrase [VERB-AUTO VCL] can code the perfective or imperfective aspect in different types of complex sentences in Hui Chinese; – More variety of auto-VCL structures is found in Hui Chinese compared with Xiang and Gan dialects. -

A Case Study in Language Change

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-17-2013 Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change Ian Hollenbaugh Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hollenbaugh, Ian, "Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change" (2013). Honors Theses. 2243. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2243 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Elementary Ghau Aethauic Grammar By Ian Hollenbaugh 1 i. Foreword This is an essential grammar for any serious student of Ghau Aethau. Mr. Hollenbaugh has done an excellent job in cataloguing and explaining the many grammatical features of one of the most complex language systems ever spoken. Now published for the first time with an introduction by my former colleague and premier Ghau Aethauic scholar, Philip Logos, who has worked closely with young Hollenbaugh as both mentor and editor, this is sure to be the definitive grammar for students and teachers alike in the field of New Classics for many years to come. John Townsend, Ph.D Professor Emeritus University of Nunavut 2 ii. Author’s Preface This grammar, though as yet incomplete, serves as my confession to what J.R.R. Tolkien once called “a secret vice.” History has proven Professor Tolkien right in thinking that this is not a bizarre or freak occurrence, undergone by only the very whimsical, but rather a common “hobby,” one which many partake in, and have partaken in since at least the time of Hildegard of Bingen in the twelfth century C.E.