A Case Study in Language Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representation of Inflected Nouns in the Internal Lexicon

Memory & Cognition 1980, Vol. 8 (5), 415423 Represeritation of inflected nouns in the internal lexicon G. LUKATELA, B. GLIGORIJEVIC, and A. KOSTIC University ofBelgrade, Belgrade, Yugoslavia and M.T.TURVEY University ofConnecticut, Storrs, Connecticut 06268 and Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, Connecticut 06510 The lexical representation of Serbo-Croatian nouns was investigated in a lexical decision task. Because Serbo-Croatian nouns are declined, a noun may appear in one of several gram matical cases distinguished by the inflectional morpheme affixed to the base form. The gram matical cases occur with different frequencies, although some are visually and phonetically identical. When the frequencies of identical forms are compounded, the ordering of frequencies is not the same for masculine and feminine genders. These two genders are distinguished further by the fact that the base form for masculine nouns is an actual grammatical case, the nominative singular, whereas the base form for feminine nouns is an abstraction in that it cannot stand alone as an independent word. Exploiting these characteristics of the Serbo Croatian language, we contrasted three views of how a noun is represented: (1) the independent entries hypothesis, which assumes an independent representation for each grammatical case, reflecting its frequency of occurrence; (2) the derivational hypothesis, which assumes that only the base morpheme is stored, with the individual cases derived from separately stored inflec tional morphemes and rules for combination; and (3) the satellite-entries hypothesis, which assumes that all cases are individually represented, with the nominative singular functioning as the nucleus and the embodiment of the noun's frequency and around which the other cases cluster uniformly. -

A Brief Description of Consonants in Modern Standard Arabic

Linguistics and Literature Studies 2(7): 185-189, 2014 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2014.020702 A Brief Description of Consonants in Modern Standard Arabic Iram Sabir*, Nora Alsaeed Al-Jouf University, Sakaka, KSA *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright © 2014 Horizon Research Publishing All rights reserved. Abstract The present study deals with “A brief Modern Standard Arabic. This study starts from an description of consonants in Modern Standard Arabic”. This elucidation of the phonetic bases of sounds classification. At study tries to give some information about the production of this point shows the first limit of the study that is basically Arabic sounds, the classification and description of phonetic rather than phonological description of sounds. consonants in Standard Arabic, then the definition of the This attempt of classification is followed by lists of the word consonant. In the present study we also investigate the consonant sounds in Standard Arabic with a key word for place of articulation in Arabic consonants we describe each consonant. The criteria of description are place and sounds according to: bilabial, labio-dental, alveolar, palatal, manner of articulation and voicing. The attempt of velar, uvular, and glottal. Then the manner of articulation, description has been made to lead to the drawing of some the characteristics such as phonation, nasal, curved, and trill. fundamental conclusion at the end of the paper. The aim of this study is to investigate consonant in MSA taking into consideration that all 28 consonants of Arabic alphabets. As a language Arabic is one of the most 2. -

Tigre and the Case of Internal Reduplication*

San Diego Linguistic Papers 1 (2003) 109-128 TRIPLE TAKE: TIGRE AND THE CASE OF * INTERNAL REDUPLICATION Sharon Rose University of California, San Diego _______________________________________________________________________ Ethiopian Semitic languages all have some form of internal reduplication. The characteristics of Tigre reduplication are described here, and are shown to diverge from the other languages in two main respects: i) the meaning and ii) the ability to incur multiple reduplication of the reduplicative syllable. The formation of internal reduplication is accomplished via infixation plus addditional templatic shape requirements which override many properties of the regular verb stem. Further constraints on realization of the full reduplicative syllable outweigh restrictions on multiple repetition of consonants, particularly gutturals. _______________________________________________________________________ 1 Introduction Ethiopian Semitic languages have a form of internal reduplication, often termed the ‘frequentative’, which is formed by means of an infixed ‘reduplicative syllable’ consisting of reduplication of the penultimate root consonant and a vowel, usually [a]: ex. Tigrinya s«bab«r« ‘break in pieces’ corresponding to the verb s«b«r« ‘break’.1 Leslau (1939) describes the semantic value of the frequentative as reiterative, intensive, augmentative or attenuative, to which one could add distributive and diminutive. This paper focuses on several aspects of internal reduplication in Tigre, the northernmost Ethio-Semitic language. I present new data demonstrating that not only does Tigre allow internal reduplication with a wide variety of verbs, but it differs notably from other Ethiopian Semitic languages in two important respects: (1) a. the meaning of the internal reduplication is normally ‘diminutive’ or represents elapsed time between action; in the other languages it is usually intensive. -

LINGUISTICS 221 LECTURE #3 the BASIC SOUNDS of ENGLISH 1. STOPS a Stop Consonant Is Produced with a Complete Closure of Airflow

LINGUISTICS 221 LECTURE #3 Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology THE BASIC SOUNDS OF ENGLISH 1. STOPS A stop consonant is produced with a complete closure of airflow in the vocal tract; the air pressure has built up behind the closure; the air rushes out with an explosive sound when released. The term plosive is also used for oral stops. ORAL STOPS: e.g., [b] [t] (= plosives) NASAL STOPS: e.g., [m] [n] (= nasals) There are three phases of stop articulation: i. CLOSING PHASE (approach or shutting phase) The articulators are moving from an open state to a closed state; ii. CLOSURE PHASE (= occlusion) Blockage of the airflow in the oral tract; iii. RELEASE PHASE Sudden reopening; it may be accompanied by a burst of air. ORAL STOPS IN ENGLISH a. BILABIAL STOPS: The blockage is made with the two lips. spot [p] voiceless baby [b] voiced 1 b. ALVEOLAR STOPS: The blade (or the tip) of the tongue makes a closure with the alveolar ridge; the sides of the tongue are along the upper teeth. lamino-alveolar stops or Check your apico-alveolar stops pronunciation! stake [t] voiceless deep [d] voiced c. VELAR STOPS: The closure is between the back of the tongue (= dorsum) and the velum. dorso-velar stops scar [k] voiceless goose [g] voiced 2. NASALS (= nasal stops) The air is stopped in the oral tract, but the velum is lowered so that the airflow can go through the nasal tract. All nasals are voiced. NASALS IN ENGLISH a. BILABIAL NASAL: made [m] b. ALVEOLAR NASAL: need [n] c. -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

The Ongoing Eclipse of Possessive Suffixes in North Saami

Te ongoing eclipse of possessive sufxes in North Saami A case study in reduction of morphological complexity Laura A. Janda & Lene Antonsen UiT Te Arctic University of Norway North Saami is replacing the use of possessive sufxes on nouns with a morphologically simpler analytic construction. Our data (>2K examples culled from >.5M words) track this change through three generations, covering parameters of semantics, syntax and geography. Intense contact pressure on this minority language probably promotes morphological simplifcation, yielding an advantage for the innovative construction. Te innovative construction is additionally advantaged because it has a wider syntactic and semantic range and is indispensable, whereas its competitor can always be replaced. Te one environment where the possessive sufx is most strongly retained even in the youngest generation is in the Nominative singular case, and here we fnd evidence that the possessive sufx is being reinterpreted as a Vocative case marker. Keywords: North Saami; possessive sufx; morphological simplifcation; vocative; language contact; minority language 1. Te linguistic landscape of North Saami1 North Saami is a Uralic language spoken by approximately 20,000 people spread across a large area in northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland. North Saami is in a unique situation as the only minority language in Europe under intense pressure from majority languages from two diferent language families, namely Finnish (Uralic) in the east and Norwegian and Swedish (Indo-European 1. Tis research was supported in part by grant 22506 from the Norwegian Research Council. Te authors would also like to thank their employer, UiT Te Arctic University of Norway, for support of their research. -

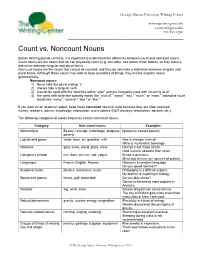

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Diachrony of Ergative Future

• THE EVOLUTION OF THE TENSE-ASPECT SYSTEM IN HINDI/URDU: THE STATUS OF THE ERGATIVE ALGNMENT Annie Montaut INALCO, Paris Proceedings of the LFG06 Conference Universität Konstanz Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2006 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ Abstract The paper deals with the diachrony of the past and perfect system in Indo-Aryan with special reference to Hindi/Urdu. Starting from the acknowledgement of ergativity as a typologically atypical feature among the family of Indo-European languages and as specific to the Western group of Indo-Aryan dialects, I first show that such an evolution has been central to the Romance languages too and that non ergative Indo-Aryan languages have not ignored the structure but at a certain point went further along the same historical logic as have Roman languages. I will then propose an analysis of the structure as a predication of localization similar to other stative predications (mainly with “dative” subjects) in Indo-Aryan, supporting this claim by an attempt of etymologic inquiry into the markers for “ergative” case in Indo- Aryan. Introduction When George Grierson, in the full rise of language classification at the turn of the last century, 1 classified the languages of India, he defined for Indo-Aryan an inner circle supposedly closer to the original Aryan stock, characterized by the lack of conjugation in the past. This inner circle included Hindi/Urdu and Eastern Panjabi, which indeed exhibit no personal endings in the definite past, but only gender-number agreement, therefore pertaining more to the adjectival/nominal class for their morphology (calâ, go-MSG “went”, kiyâ, do- MSG “did”, bola, speak-MSG “spoke”). -

Oksana's BU Paper

ACQUISITION of GENDER in RUSSIAN * Oksana Tarasenkova University of Connecticut 1 The Background In adult Russian grammar the gender feature of nouns is closely related to their declension class. Their relationship was a controversial question that evoked two opposing views regarding the way gender is represented in adult Russian grammar. The representatives of one view argue for gender to be derived from the noun declension class (Declension-to Gender account, Corbett 1982), while proponents of the opposite account argue for the reversed pattern, where the inflectional morphology can be predicted from the information on the noun gender along with a phonological cue (Gender-to-Declension account, Vinogradov 1960, Thelin 1975, Crockett 1976 among others). My goal is to focus on children’s acquisition of gender in Russian in order to compare these two major divisions of research. They provide different morphological analyses of gender forms in Russian; therefore this debate makes different predictions about the acquisition of gender by children. I tested these opposing predictions using children’s data gathered from an experiment to identify what exactly children rely on when assigning gender to nouns. The experiment results support the Declension-to-Gender view and provide evidence that children are significantly more successful at assigning gender to the novel nouns relying on the nominal declension paradigm rather than on the adjectival agreement. The way gender is represented in adults’ competence grammar might not necessarily be the correct model of children’s acquisition of gender. The child has to learn the gender of a significant number of nouns and extract the declensional paradigms first in order to then be able to learn and apply these redundancy rules for novel nouns. -

Systemic Polyfunctionality and Morphology-Syntax Interdependencies

Systemic polyfunctionality and morphology-syntax interdependencies Farrell Ackerman1 Olivier Bonami2 Irina Nikolaeva3 1University of California, San Diego 2Université Paris-Sorbonne 3SOAS Defaults in Morphological Theory Lexington, May 2012 The basic problem: Systemic Polyfunctionality Cross-linguistically person/number markers (PNMs) in verbal paradigms often exhibit similarities (up to identity) with person/number markers in nominal possessive constructions (Allen 1964, Radics 1980, Siewierska 1998, 2004, among others): When a language has distinct PNM paradigms for verbal subject (S/A) and object (O) indexing, a question arises: Which paradigm does the possessive paradigm align with? (1) Retuarã (Tucanoan) S/A alignment b˜ıre yi-ha¯a-a¯ Psi yi-behoa-pi 2SG 1SG-kill-NEG.IMP 1SG-spear-INSTR ‘(Be careful), lest I kill you with my spear’ (Strom 1992:63) (2) Kilivila (Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian) O alignment lube-gu ku-sake-gu buva friend-1SG 2SG-give-1SG betel_nut ‘My friend, do you give me betel nuts?’ (Senft 1986:53) The basic problem: Systemic Polyfunctionality Among the 130 relevant languages in Sierwieska’s (1998) sample she observes that, We see that [...], among the languages in the sample the affinities in form between the possessor affixes and the verbal person markers of the O (41%) are just marginally more common than those with the S/A (39%). (Siewierska 1998:2) There are, by hypothesis, systemic properties of specific grammars, rather than language independent universals, that explain the alignments observed. The languages compared by Siewierska appear to have distinct markers for S/A and O, and the question asked is which paradigm appears in possessive marking. -

Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds

Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds Their Diachronic Development Within the Greek Compound System Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS ISBN 978-3-11-041576-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041582-7 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041586-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Umschlagabbildung: Paul Klee: Einst dem Grau der Nacht enttaucht …, 1918, 17. Aquarell, Feder und Bleistit auf Papier auf Karton. 22,6 x 15,8 cm. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern. Typesetting: Dr. Rainer Ostermann, München Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS This book is for Arturo, who has waited so long. Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Preface and Acknowledgements Preface and Acknowledgements I have always been ὀψιανθής, a ‘late-bloomer’, and this book is a testament to it. -

The Production of Lexical Tone in Croatian

The production of lexical tone in Croatian Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie im Fachbereich Sprach- und Kulturwissenschaften der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität zu Frankfurt am Main vorgelegt von Jevgenij Zintchenko Jurlina aus Kiew 2018 (Einreichungsjahr) 2019 (Erscheinungsjahr) 1. Gutacher: Prof. Dr. Henning Reetz 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Sven Grawunder Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 01.11.2018 ABSTRACT Jevgenij Zintchenko Jurlina: The production of lexical tone in Croatian (Under the direction of Prof. Dr. Henning Reetz and Prof. Dr. Sven Grawunder) This dissertation is an investigation of pitch accent, or lexical tone, in standard Croatian. The first chapter presents an in-depth overview of the history of the Croatian language, its relationship to Serbo-Croatian, its dialect groups and pronunciation variants, and general phonology. The second chapter explains the difference between various types of prosodic prominence and describes systems of pitch accent in various languages from different parts of the world: Yucatec Maya, Lithuanian and Limburgian. Following is a detailed account of the history of tone in Serbo-Croatian and Croatian, the specifics of its tonal system, intonational phonology and finally, a review of the most prominent phonetic investigations of tone in that language. The focal point of this dissertation is a production experiment, in which ten native speakers of Croatian from the region of Slavonia were recorded. The material recorded included a diverse selection of monosyllabic, bisyllabic, trisyllabic and quadrisyllabic words, containing all four accents of standard Croatian: short falling, long falling, short rising and long rising. Each target word was spoken in initial, medial and final positions of natural Croatian sentences.