Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

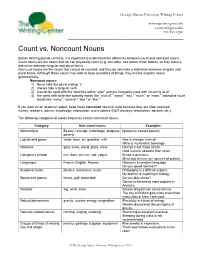

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Syntactic Variation in English Quantified Noun Phrases with All, Whole, Both and Half

Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Acta Wexionensia Nr 38/2004 Humaniora Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Maria Estling Vannestål Växjö University Press Abstract Estling Vannestål, Maria, 2004. Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half, Acta Wexionensia nr 38/2004. ISSN: 1404-4307, ISBN: 91-7636-406-2. Written in English. The overall aim of the present study is to investigate syntactic variation in certain Present-day English noun phrase types including the quantifiers all, whole, both and half (e.g. a half hour vs. half an hour). More specific research questions concerns the overall frequency distribution of the variants, how they are distrib- uted across regions and media and what linguistic factors influence the choice of variant. The study is based on corpus material comprising three newspapers from 1995 (The Independent, The New York Times and The Sydney Morning Herald) and two spoken corpora (the dialogue component of the BNC and the Longman Spoken American Corpus). The book presents a number of previously not discussed issues with respect to all, whole, both and half. The study of distribution shows that one form often predominated greatly over the other(s) and that there were several cases of re- gional variation. A number of linguistic factors further seem to be involved for each of the variables analysed, such as the syntactic function of the noun phrase and the presence of certain elements in the NP or its near co-text. -

Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1

Eun-Joo Kwak 55 Journal of Universal Language 15-2 September 2014, 55-76 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1 2 Eun-Joo Kwak Sejong University, Korea Abstract Countability and plurality (or singularity) are basically marked in syntax or morphology, and languages adopt different strategies in the mass-count distinction and number marking: plural marking, unmarked number marking, singularization, and different uses of classifiers. Diverse patterns of grammatical strategies are observed with cross-linguistic data in this study. Based on this, it is concluded that although countability is not solely determined by the semantic properties of nouns, it is much more affected by semantics than it appears. Moreover, semantic features of nouns are useful to account for apparent idiosyncratic behaviors of nouns and sentences. Keywords: countability, plurality, countability shift, individuation, animacy, classifier * This work is supported by the Sejong University Research Grant of 2013. Eun-Joo Kwak Department of English Language and Literature, Sejong University, Seoul, Korea Phone: +82-2-3408-3633; Email: [email protected] Received August 14, 2014; Revised September 3, 2014; Accepted September 10, 2014. 56 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability 1. Introduction The state of affairs in the real world may be delivered in a different way depending on the grammatical properties of languages. Nominal countability makes part of grammatical differences cross-linguistically, marked in various ways: plural (or singular) morphemes for nouns or verbs, distinct uses of determiners, and the occurrences of classifiers. Apparently, countability and plurality are mainly marked in syntax and morphology, so they may be understood as having less connection to the semantic features of nouns. -

3 Types of Anaphors

3 Types of anaphors Moving from the definition and characteristics of anaphors to the types of ana- phors, this chapter will detail the nomenclature of anaphor types established for this book. In general, anaphors can be categorised according to: their form; the type of relationship to their antecedent; the form of their antecedents; the position of anaphors and antecedents, i.e. intrasentential or intersentential; and other features (cf. Mitkov 2002: 8-17). The procedure adopted here is to catego- rise anaphors according to their form. It should be stressed that the types dis- tinguished in this book are not universal categories, so the proposed classifica- tion is not the only possible solution. For instance, personal, possessive and re- flexive pronouns can be seen as three types or as one type. With the latter, the three pronoun classes are subsumed under the term “central pronouns”, as it is adopted here. Linguistic classifications of anaphors can be found in two established gram- mar books, namely in Quirk et al.’s A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language (2012: 865) and in The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (Stirling & Huddleston 2010: 1449-1564). Quirk et al. include a chapter of pro- forms and here distinguish between coreference and substitution. However, they do not take anaphors as their starting point of categorisation. Additionally, Stirling & Huddleston do not consider anaphors on their own but together with deixis. As a result, anaphoric noun phrases with a definite article, for example, are not included in both categorisations. Furthermore, Schubert (2012: 31-55) presents a text-linguistic view, of which anaphors are part, but his classification is similarly unsuitable because it does not focus on the anaphoric items specifi- cally. -

English 4 Using Clear and Coherent Sentences Employing Grammatical Structures Second Quarter - Week 2

Department of Education English 4 Using Clear and Coherent Sentences employing Grammatical Structures Second Quarter - Week 2 Adelinda D. Dollesin Writer Hilario G. Canasa Dr. Ma. Myra E. Namit Validators Ivy M. Romano Ada T. Tagle Cecilia Theresa C. Claudel Dr. Ma. Theresa C. Dela Rosa Dr. Ma. Carmen D. Solayao Dr. Shella C. Navarro Quality Assurance Team Schools Division Office – Muntinlupa City Student Center for Life Skills Bldg., Centennial Ave., Brgy. Tunasan, Muntinlupa City (02) 8805-9935 / (02) 8805-9940 1 This module was designed to help you master the use of clear and coherent sentences employing appropriate grammatical structures (Kinds of Nouns: Count and Mass, Possessive and Collective Nouns) After going through this module, you are expected to: 1. Define and identify the kinds of nouns: mass and count nouns, possessive and collective nouns; and 2. Classify and use kinds of nouns (mass and count nouns, possessive and collective nouns) in simple sentence. A. Directions: Encircle the letter of the correct answer. 1. Linda will buy juice and chicken from the store. Which of the following words is a mass noun? A. chicken C. Linda B. juice D. store 2. Nena will use the long spoon for halo-halo. Which of the following is a count noun? A. Long C. use B. spoon D. will 3. They put sugar in the jar. What is the count noun in the sentence? A. jar C. sugar B. put D. they 4. Hera added rice in a bowl. Which is the mass noun in the sentence? A. bowl C. Hera B. -

A Case Study in Language Change

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-17-2013 Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change Ian Hollenbaugh Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hollenbaugh, Ian, "Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change" (2013). Honors Theses. 2243. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2243 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Elementary Ghau Aethauic Grammar By Ian Hollenbaugh 1 i. Foreword This is an essential grammar for any serious student of Ghau Aethau. Mr. Hollenbaugh has done an excellent job in cataloguing and explaining the many grammatical features of one of the most complex language systems ever spoken. Now published for the first time with an introduction by my former colleague and premier Ghau Aethauic scholar, Philip Logos, who has worked closely with young Hollenbaugh as both mentor and editor, this is sure to be the definitive grammar for students and teachers alike in the field of New Classics for many years to come. John Townsend, Ph.D Professor Emeritus University of Nunavut 2 ii. Author’s Preface This grammar, though as yet incomplete, serves as my confession to what J.R.R. Tolkien once called “a secret vice.” History has proven Professor Tolkien right in thinking that this is not a bizarre or freak occurrence, undergone by only the very whimsical, but rather a common “hobby,” one which many partake in, and have partaken in since at least the time of Hildegard of Bingen in the twelfth century C.E. -

Count Nouns - Mass Nouns, Neat Nouns - Mess Nouns

Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication Volume 6 FORMAL SEMANTICS AND PRAGMATICS. DISCOURSE, CONTEXT AND Article 12 MODELS 2011 Count Nouns - Mass Nouns, Neat Nouns - Mess Nouns Fred Landman Linguistics Department Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/biyclc This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Landman, Fred (2011) "Count Nouns - Mass Nouns, Neat Nouns - Mess Nouns," Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication: Vol. 6. https://doi.org/10.4148/biyclc.v6i0.1579 This Proceeding of the Symposium for Cognition, Logic and Communication is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mass Nouns 2 The Baltic International Yearbook of I will discuss grinding interpretations of count nouns, here Cognition, Logic and Communication rebaptized fission interpretations, and argue that these interpre- tations differ in crucial ways from the interpretations of lexical October 2011 Volume 6: Formal Semantics and Pragmatics: mass nouns. The paper will end with a foundational problem Discourse, Context, and Models raised by fission interpretations, and in the course of this, atom- pages 1-67 DOI: 10.4148/biyclc.v6i0.1579 less interpretation domains will re-enter the scene through the back door. FRED LANDMAN 1. ...OR NOT TO COUNT Linguistics Department Tel Aviv University Count nouns, like boy, can be counted, mass nouns, like salt, cannot: (1) a. -

![Count and Noncount Nouns [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1666/count-and-noncount-nouns-pdf-1721666.webp)

Count and Noncount Nouns [Pdf]

San José State University Writing Center www.sjsu.edu/writingcenter Written by Peter Gambrill Count and Noncount Nouns A noun is a person, place, thing, or idea. However, nouns can be separated into two categories: count and noncount. Count nouns refer to a singular entity. Examples: tree, car, book, airplane, fork, wall, desk, shirt Noncount nouns refer to either an undifferentiated mass or an abstract idea that, as the name implies, cannot be counted. Examples: wood, sugar, justice, purity, milk, water, furniture, joy, mail, news, luggage Differentiating between Count and Noncount Nouns There are several ways to differentiate between the two classes of nouns. While both types of nouns can be designated by the definite article the, only count nouns can be used with the indefinite article a. Examples: You can say both a car and the car, but you can only say the sugar, not a sugar. Only count nouns can be plural. Examples: You can say roads, groups, and guitars, but you cannot say milks, mails, or furnitures. A few nouns can be used as either count or noncount. Wood, as a building or burning material, is a noncount noun. As such, the clause “the monastery was built of woods” doesn’t make sense. But when the word refers to forest(s), it is a count noun. Count nouns can also combine with certain determiners, such as one, two, these, several, many, or few. Determiners are words that precede nouns. Some describe the quantity of a noun (like those above), while others describe whether a noun is specific or not. -

1 97. Count/Mass Distinctions Across Languages 1. Outline 2. Correlates

1 Jenny Doetjes, LUCL, [email protected] To appear in: Semantics: an international handbook of natural language meaning , part III, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger and Paul Portner. Berlin: De Gruyter. 97. Count/mass distinctions across languages 1. Outline 2. Correlates of the count/mass distinction 3. The Sanches-Greenberg-Slobin generalization 4. Count versus mass in the lexicon 5. Conclusions: count and mass across languages 6. References This article examines the opposition between count and mass in a variety of languages. It starts by an overview of correlates of the count/mass distinction, illustrated by data from three types of languages: languages with morphological number marking, languages with numeral classifiers and languages with neither of these. Despite the differences, the count/mass distinction can be shown to play a role in all three systems. The second part of the paper focuses on the Sanches-Greenberg- Slobin generalization, which states that numeral classifier languages do not have obligatory morphological number marking on nouns. Finally the paper discusses the relation between the count/mass distinction and the lexicon. 1. Outline The first question to ask when looking at the count/mass distinction from a cross- linguistic point of view is whether this distinction plays a role in all languages, and if so, whether it plays a similar role. Obviously, all languages include means to refer both to individuals (in a broad sense) and to masses. However, it is a matter of debate whether the distinction between count and mass plays a role in the linguistic system of all languages, whether it should be made at a lexical level, and whether all languages are alike in this respect. -

The Grammar of Individuation and Counting Suzi Lima

University of Massachusetts - Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 2014-current Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-9-2014 The Grammar of Individuation and Counting Suzi Lima Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 2014-current by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GRAMMAR OF INDIVIDUATION AND COUNTING A Dissertation Presented by SUZI OLIVEIRA DE LIMA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2014 Department of Linguistics © Copyright by Suzi Oliveira de Lima 2014 All Rights Reserved THE GRAMMAR OF INDIVIDUATION AND COUNTING A Dissertation Presented by SUZI OLIVEIRA DE LIMA Approved as to style and content by: __________________________________________ Lyn Frazier, Co-chair __________________________________________ Angelika Kratzer, Co-chair __________________________________________ Gennaro Chierchia, Member __________________________________________ Seth Cable, Member __________________________________________ Charles Clifton Jr., Member ________________________________________ John Kingston, Department Head Linguistics department DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated with love to my parents Raimundo and Sirlei and to the dear Yudja people whose friendship and support brought me here. Esta dissertação é dedicada com amor aos meus pais, Raimundo e Sirlei, e também para o querido povo Yudja cuja amizade e apoio me trouxeram até aqui. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, this dissertation exists because of the enormous generosity and kindness of the Yudja people who have been working with me since I was an undergraduate student. -

1 the Powerful Mix of Animacy and Initial Position: a Psycholinguistic

The powerful mix of animacy and initial position: A psycholinguistic investigation of Estonian case and subjecthood Elsi Kaiser*, Merilin Miljan†§, Virve-Anneli Vihman§‡ *Univ. of Southern California, †Univ. of Tallinn, §Univ. of Tartu, ‡Univ. of Manchester [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Forty Years after Keenan 1976, 7–9 September 2016 Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium • When defining grammatical relations, we often prioritize morphological and syntactic properties, such as case-marking, agreement, linear position (see, e.g., Keenan 1976, Keenan and Comrie 1977) over meaning-related criteria (e.g. animacy). o Subject in nominative-accusative languages is typically in nominative case. o Pre-verbal/clause-initial noun phrase is the subject (e.g. English) Estonian, a nominative-accusative language, presents an interesting example: • three different morphological cases – NOM, PART, GEN – are used for marking the core arguments, subject and object: o Subject is marked by two of these: NOM and PART (section 1) o Object is marked by NOM, PART and GEN (section 1.1) • flexible word order, i.e. pre-verbal position does not define subjecthood (section 1.2) Þ all three core cases are syntactically ambiguous, while the constituent order is free Questions: How do the (prototypical) morphological and syntactic properties of subjects – case marking and linear position – cue for the grammatical role of subject in Estonian? • What information influences the interpretation of the subject relation in Estonian? • Is case in Estonian a stronger subjecthood feature than word order, because in terms of frequency, the position of the subject varies? This talk: We report on two psycholinguistic experiments: participants were shown case- marked nouns and asked to use them in a sentence. -

Countability Distinctions and Semantic Variation

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Countability Distinctions and Semantic Variation Amy Rose Deal Abstract To what extent are countability distinctions subject to systematic semantic variation? Could there be a language with no countability distinctions–in particular, one where all nounsare count? I arguethat the answer is no: even in a languagewhere all NPs have the core morphosyntactic properties of English count NPs, such as com- bining with numerals directly and showing singular/plural distinctions, countability distinctions still emerge on close inspection. I divide these distinctions into those related to sums (cumulativity) and those related to parts (divisiveness, atomicity and related notions). In the Sahaptian language Nez Perce, evidence can be foundfor both types of distinction, in spite of the absence of anything like a traditional mass-count distinction in noun morphosyntax. I propose an extension of the Nez Perce analysis to Yudja (Tupi), analyzed by Lima (2014) as lacking any countability distinctions. More generally, I suggest that at least one countability distinction may be universal and that languages without any countability distinctions may be unlearnable. 1 Introduction Cat is a count noun; blood is not. What is this difference? Much recent work has argued that nouns like these are actually different along two dimensions related to countability, not just one. The central argument comes from the behavior of nouns like footwear and jewelry, which behave like cat in certain respects and like blood in others. In terms of pluralization, for instance, footwear behaves like blood, (1); in I would like to express my thanks to Gennaro Chierchia, Kate Davidson, Angelika Kratzer, Manfred Krifka, Sarah Murray, Greg Scontras, audiences at Berkeley, UCSC, Sinn und Bedeutung 20 in Tübin- gen, SULA 8 in Vancouver, the workshop ‘Toward a theory of syntactic variation’ in Bilbao, and the workshop on Semantic Variation in Chicago, for helpful comments and questions.