Countability Distinctions and Semantic Variation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

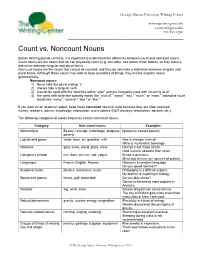

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Syntactic Variation in English Quantified Noun Phrases with All, Whole, Both and Half

Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Acta Wexionensia Nr 38/2004 Humaniora Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Maria Estling Vannestål Växjö University Press Abstract Estling Vannestål, Maria, 2004. Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half, Acta Wexionensia nr 38/2004. ISSN: 1404-4307, ISBN: 91-7636-406-2. Written in English. The overall aim of the present study is to investigate syntactic variation in certain Present-day English noun phrase types including the quantifiers all, whole, both and half (e.g. a half hour vs. half an hour). More specific research questions concerns the overall frequency distribution of the variants, how they are distrib- uted across regions and media and what linguistic factors influence the choice of variant. The study is based on corpus material comprising three newspapers from 1995 (The Independent, The New York Times and The Sydney Morning Herald) and two spoken corpora (the dialogue component of the BNC and the Longman Spoken American Corpus). The book presents a number of previously not discussed issues with respect to all, whole, both and half. The study of distribution shows that one form often predominated greatly over the other(s) and that there were several cases of re- gional variation. A number of linguistic factors further seem to be involved for each of the variables analysed, such as the syntactic function of the noun phrase and the presence of certain elements in the NP or its near co-text. -

Number and Adjectives : the Case of Activity and Quality Nominals Delphine Beauseroy, Marie-Laurence Knittel

Number and adjectives : the case of activity and quality nominals Delphine Beauseroy, Marie-Laurence Knittel To cite this version: Delphine Beauseroy, Marie-Laurence Knittel. Number and adjectives : the case of activity and quality nominals. 2012. hal-00418040v2 HAL Id: hal-00418040 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00418040v2 Preprint submitted on 11 Jun 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 NUMBER AND ADJECTIVES: THE CASE OF FRENCH ACTIVITY AND QUALITY NOMINALS 1. INTRODUCTION This article is dedicated to the examination of the role of Number with regards to adjective distribution in French. We focus on two kinds of abstract nouns: activity nominals and quality nominals. Both display particular behaviours with regards to adjective distribution: activity nominals need to appear as count nouns to be modified by qualifying adjectives; concerning quality nominals, they are frequently introduced by the indefinite un(e) instead of the partitive article (du / de la) when modified. Our analysis of adjectives is based on the idea that they can have two uses, which correlate with syntactic and semantic restrictions and are distinguishable on semantic grounds. Adjectives are understood either as taxonomic, i.e. -

Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1

Eun-Joo Kwak 55 Journal of Universal Language 15-2 September 2014, 55-76 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1 2 Eun-Joo Kwak Sejong University, Korea Abstract Countability and plurality (or singularity) are basically marked in syntax or morphology, and languages adopt different strategies in the mass-count distinction and number marking: plural marking, unmarked number marking, singularization, and different uses of classifiers. Diverse patterns of grammatical strategies are observed with cross-linguistic data in this study. Based on this, it is concluded that although countability is not solely determined by the semantic properties of nouns, it is much more affected by semantics than it appears. Moreover, semantic features of nouns are useful to account for apparent idiosyncratic behaviors of nouns and sentences. Keywords: countability, plurality, countability shift, individuation, animacy, classifier * This work is supported by the Sejong University Research Grant of 2013. Eun-Joo Kwak Department of English Language and Literature, Sejong University, Seoul, Korea Phone: +82-2-3408-3633; Email: [email protected] Received August 14, 2014; Revised September 3, 2014; Accepted September 10, 2014. 56 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability 1. Introduction The state of affairs in the real world may be delivered in a different way depending on the grammatical properties of languages. Nominal countability makes part of grammatical differences cross-linguistically, marked in various ways: plural (or singular) morphemes for nouns or verbs, distinct uses of determiners, and the occurrences of classifiers. Apparently, countability and plurality are mainly marked in syntax and morphology, so they may be understood as having less connection to the semantic features of nouns. -

3 Types of Anaphors

3 Types of anaphors Moving from the definition and characteristics of anaphors to the types of ana- phors, this chapter will detail the nomenclature of anaphor types established for this book. In general, anaphors can be categorised according to: their form; the type of relationship to their antecedent; the form of their antecedents; the position of anaphors and antecedents, i.e. intrasentential or intersentential; and other features (cf. Mitkov 2002: 8-17). The procedure adopted here is to catego- rise anaphors according to their form. It should be stressed that the types dis- tinguished in this book are not universal categories, so the proposed classifica- tion is not the only possible solution. For instance, personal, possessive and re- flexive pronouns can be seen as three types or as one type. With the latter, the three pronoun classes are subsumed under the term “central pronouns”, as it is adopted here. Linguistic classifications of anaphors can be found in two established gram- mar books, namely in Quirk et al.’s A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language (2012: 865) and in The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (Stirling & Huddleston 2010: 1449-1564). Quirk et al. include a chapter of pro- forms and here distinguish between coreference and substitution. However, they do not take anaphors as their starting point of categorisation. Additionally, Stirling & Huddleston do not consider anaphors on their own but together with deixis. As a result, anaphoric noun phrases with a definite article, for example, are not included in both categorisations. Furthermore, Schubert (2012: 31-55) presents a text-linguistic view, of which anaphors are part, but his classification is similarly unsuitable because it does not focus on the anaphoric items specifi- cally. -

English 4 Using Clear and Coherent Sentences Employing Grammatical Structures Second Quarter - Week 2

Department of Education English 4 Using Clear and Coherent Sentences employing Grammatical Structures Second Quarter - Week 2 Adelinda D. Dollesin Writer Hilario G. Canasa Dr. Ma. Myra E. Namit Validators Ivy M. Romano Ada T. Tagle Cecilia Theresa C. Claudel Dr. Ma. Theresa C. Dela Rosa Dr. Ma. Carmen D. Solayao Dr. Shella C. Navarro Quality Assurance Team Schools Division Office – Muntinlupa City Student Center for Life Skills Bldg., Centennial Ave., Brgy. Tunasan, Muntinlupa City (02) 8805-9935 / (02) 8805-9940 1 This module was designed to help you master the use of clear and coherent sentences employing appropriate grammatical structures (Kinds of Nouns: Count and Mass, Possessive and Collective Nouns) After going through this module, you are expected to: 1. Define and identify the kinds of nouns: mass and count nouns, possessive and collective nouns; and 2. Classify and use kinds of nouns (mass and count nouns, possessive and collective nouns) in simple sentence. A. Directions: Encircle the letter of the correct answer. 1. Linda will buy juice and chicken from the store. Which of the following words is a mass noun? A. chicken C. Linda B. juice D. store 2. Nena will use the long spoon for halo-halo. Which of the following is a count noun? A. Long C. use B. spoon D. will 3. They put sugar in the jar. What is the count noun in the sentence? A. jar C. sugar B. put D. they 4. Hera added rice in a bowl. Which is the mass noun in the sentence? A. bowl C. Hera B. -

A Case Study in Language Change

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-17-2013 Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change Ian Hollenbaugh Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hollenbaugh, Ian, "Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change" (2013). Honors Theses. 2243. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2243 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Elementary Ghau Aethauic Grammar By Ian Hollenbaugh 1 i. Foreword This is an essential grammar for any serious student of Ghau Aethau. Mr. Hollenbaugh has done an excellent job in cataloguing and explaining the many grammatical features of one of the most complex language systems ever spoken. Now published for the first time with an introduction by my former colleague and premier Ghau Aethauic scholar, Philip Logos, who has worked closely with young Hollenbaugh as both mentor and editor, this is sure to be the definitive grammar for students and teachers alike in the field of New Classics for many years to come. John Townsend, Ph.D Professor Emeritus University of Nunavut 2 ii. Author’s Preface This grammar, though as yet incomplete, serves as my confession to what J.R.R. Tolkien once called “a secret vice.” History has proven Professor Tolkien right in thinking that this is not a bizarre or freak occurrence, undergone by only the very whimsical, but rather a common “hobby,” one which many partake in, and have partaken in since at least the time of Hildegard of Bingen in the twelfth century C.E. -

Count Nouns - Mass Nouns, Neat Nouns - Mess Nouns

Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication Volume 6 FORMAL SEMANTICS AND PRAGMATICS. DISCOURSE, CONTEXT AND Article 12 MODELS 2011 Count Nouns - Mass Nouns, Neat Nouns - Mess Nouns Fred Landman Linguistics Department Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/biyclc This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Landman, Fred (2011) "Count Nouns - Mass Nouns, Neat Nouns - Mess Nouns," Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication: Vol. 6. https://doi.org/10.4148/biyclc.v6i0.1579 This Proceeding of the Symposium for Cognition, Logic and Communication is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mass Nouns 2 The Baltic International Yearbook of I will discuss grinding interpretations of count nouns, here Cognition, Logic and Communication rebaptized fission interpretations, and argue that these interpre- tations differ in crucial ways from the interpretations of lexical October 2011 Volume 6: Formal Semantics and Pragmatics: mass nouns. The paper will end with a foundational problem Discourse, Context, and Models raised by fission interpretations, and in the course of this, atom- pages 1-67 DOI: 10.4148/biyclc.v6i0.1579 less interpretation domains will re-enter the scene through the back door. FRED LANDMAN 1. ...OR NOT TO COUNT Linguistics Department Tel Aviv University Count nouns, like boy, can be counted, mass nouns, like salt, cannot: (1) a. -

Unmarked Plurals

Unmarked Plurals Yasu Sudo Lecture 1 UCL Masaryk University [email protected] 12 December, 2017 1 Number Morphology Many languages morphologically mark number in the nominal domain (nouns and pronouns):1 1.1 English English marks singular vs. plural. (1) singular plural a. room rooms b. man men c. child children d. him them ‘Singular’ actually might be a misnomer, given that some singular-looking nouns are mass nouns (we’ll come back to this). The default plural marking in English is suffixation to the singular, ‘Nsg+s’. Other crosslinguistically common ways include (cf. Corbett 2000:§5.3): • Apophony (word-internal sound change): e.g. goose vs. geese, mouse vs. mice in English • Inflectional class: common in Slavic languages, e.g. ‘room’ in Russian (2) singular plural Nom komnat-a komnat-y Acc komnat-u komnat-y Gen komnat-y komnat Dat komnat-e komnat-am Inst komnat-oj komnat-ami Loc komnat-e komnat-ax (Russian) This is different from e.g. Turkic languages where the plural morpheme can be singled out. E.g. olma ‘apple’ in Uzbek: (3) singular plural Nom olma olma-lar Acc olma-ni olma-lar-ni Gen olma-niŋ olma-lar-niŋ Dat olma-ga olma-lar-ga Abl olma-dan olma-lar-dan Loc olma-da olma-lar-da (Uzbek; Corbett 2000:p. 145) • Suppletive stems: e.g. hou[s] vs. hou[z]es in English, člověk vs. lidé ‘person’ in Czech 1Corbett (2000:§2.4) mentions Pirahã (Mura; Brazil) and Kawi (Old Javanese) as languages that might lack number marking altogether. -

![Count and Noncount Nouns [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1666/count-and-noncount-nouns-pdf-1721666.webp)

Count and Noncount Nouns [Pdf]

San José State University Writing Center www.sjsu.edu/writingcenter Written by Peter Gambrill Count and Noncount Nouns A noun is a person, place, thing, or idea. However, nouns can be separated into two categories: count and noncount. Count nouns refer to a singular entity. Examples: tree, car, book, airplane, fork, wall, desk, shirt Noncount nouns refer to either an undifferentiated mass or an abstract idea that, as the name implies, cannot be counted. Examples: wood, sugar, justice, purity, milk, water, furniture, joy, mail, news, luggage Differentiating between Count and Noncount Nouns There are several ways to differentiate between the two classes of nouns. While both types of nouns can be designated by the definite article the, only count nouns can be used with the indefinite article a. Examples: You can say both a car and the car, but you can only say the sugar, not a sugar. Only count nouns can be plural. Examples: You can say roads, groups, and guitars, but you cannot say milks, mails, or furnitures. A few nouns can be used as either count or noncount. Wood, as a building or burning material, is a noncount noun. As such, the clause “the monastery was built of woods” doesn’t make sense. But when the word refers to forest(s), it is a count noun. Count nouns can also combine with certain determiners, such as one, two, these, several, many, or few. Determiners are words that precede nouns. Some describe the quantity of a noun (like those above), while others describe whether a noun is specific or not. -

1 97. Count/Mass Distinctions Across Languages 1. Outline 2. Correlates

1 Jenny Doetjes, LUCL, [email protected] To appear in: Semantics: an international handbook of natural language meaning , part III, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger and Paul Portner. Berlin: De Gruyter. 97. Count/mass distinctions across languages 1. Outline 2. Correlates of the count/mass distinction 3. The Sanches-Greenberg-Slobin generalization 4. Count versus mass in the lexicon 5. Conclusions: count and mass across languages 6. References This article examines the opposition between count and mass in a variety of languages. It starts by an overview of correlates of the count/mass distinction, illustrated by data from three types of languages: languages with morphological number marking, languages with numeral classifiers and languages with neither of these. Despite the differences, the count/mass distinction can be shown to play a role in all three systems. The second part of the paper focuses on the Sanches-Greenberg- Slobin generalization, which states that numeral classifier languages do not have obligatory morphological number marking on nouns. Finally the paper discusses the relation between the count/mass distinction and the lexicon. 1. Outline The first question to ask when looking at the count/mass distinction from a cross- linguistic point of view is whether this distinction plays a role in all languages, and if so, whether it plays a similar role. Obviously, all languages include means to refer both to individuals (in a broad sense) and to masses. However, it is a matter of debate whether the distinction between count and mass plays a role in the linguistic system of all languages, whether it should be made at a lexical level, and whether all languages are alike in this respect.