Syntactic Variation in English Quantified Noun Phrases with All, Whole, Both and Half

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learn Pronouns As Part of Speech for Bank & SSC Exams

Learn Pronouns as Part of Speech for Bank & SSC Exams - English Notes in PDF Are you preparing for Banking or SSC Exams? If you aim at making a career in the government sector & get a reputed job, it is very important to know the basics of English Language. To score maximum marks in this section with great accuracy, it is important for you to be prepared with the basic grammar & vocabulary. Here we are with a detailed explanatory article on Pronouns as Part of Speech with relevant examples. So, read the article carefully & then take our Online Mock Tests to check your level of preparation. Before moving ahead with Pronouns, let’s have a look at what are parts of speech in brief: Parts of Speech Parts of speech are the basic categories of words according to their function in a sentence. It is a category to which a word is assigned in accordance with its syntactic functions. English has eight main parts of speech, namely, Nouns, Pronouns, Adjectives, Verbs, Adverbs, Prepositions, Conjunctions & Interjections. In grammar, the parts of speech, also called lexical categories, grammatical categories or word classes is a linguistic category of words. Pronouns as Part of Speech 1 | Pronouns as part of speech are the words which are used in place of nouns like people, places, or things. They are used to avoid sounding unnatural by reusing the same noun in a sentence multiple times. In the sentence Maya saw Sanjay, and she waved at him, the pronouns she and him take the place of Maya and Sanjay, respectively. -

An Analysis of the Content Words Used in a School Textbook, Team up English 3, Used for Grade 9 Students

[Pijarnsarid et. al., Vol.5 (Iss.3): March, 2017] ISSN- 2350-0530(O), ISSN- 2394-3629(P) ICV (Index Copernicus Value) 2015: 71.21 IF: 4.321 (CosmosImpactFactor), 2.532 (I2OR) InfoBase Index IBI Factor 3.86 Social AN ANALYSIS OF THE CONTENT WORDS USED IN A SCHOOL TEXTBOOK, TEAM UP ENGLISH 3, USED FOR GRADE 9 STUDENTS Sukontip Pijarnsarid*1, Prommintra Kongkaew2 *1, 2English Department, Graduate School, Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University, Thailand DOI: https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v5.i3.2017.1761 Abstract The purpose of this study were to study the content words used in a school textbook, Team Up in English 3, used for Grade 9 students and to study the frequency of content words used in a school textbook, Team Up in English 3, used for Grade 9 students. The study found that nouns is used with the highest frequency (79), followed by verb (58), adjective (46), and adverb (24).With the nouns analyzed, it was found that the Modifiers + N used with the highest frequency (92.40%), the compound nouns were ranked in second (7.59 %). Considering the verbs used in the text, it was found that transitive verbs were most commonly used (77.58%), followed by intransitive verbs (12.06%), linking verbs (10.34%). As regards the adjectives used in the text, there were 46 adjectives in total, 30 adjectives were used as attributive (65.21 %) and 16 adjectives were used as predicative (34.78%). As for the adverbs, it was found that adverbs of times were used with the highest frequency (37.5 % ), followed by the adverbs of purpose and degree (33.33%) , the adverbs of frequency (12.5 %) , the adverbs of place ( 8.33% ) and the adverbs of manner ( 8.33 % ). -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

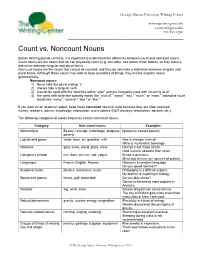

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

ASYMMETRIES in the PROSODIC PHRASING of FUNCTION WORDS: ANOTHER LOOK at the SUFFIXING PREFERENCE Nikolaus P

ASYMMETRIES IN THE PROSODIC PHRASING OF FUNCTION WORDS: ANOTHER LOOK AT THE SUFFIXING PREFERENCE Nikolaus P. Himmelmann Universität zu Köln It is a well-known fact that across the world’s languages there is a fairly strong asymmetry in the affixation of grammatical material, in that suffixes considerably outnumber prefixes in typo - logical databases. This article argues that prosody, specifically prosodic phrasing, plays an impor - tant part in bringing about this asymmetry. Prosodic word and phrase boundaries may occur after a clitic function word preceding its lexical host with sufficient frequency so as to impede the fu - sion required for affixhood. Conversely, prosodic boundaries rarely, if ever, occur between a lexi - cal host and a clitic function word following it. Hence, prosody does not impede the fusion process between lexical hosts and postposed function words, which therefore become affixes more easily. Evidence for the asymmetry in prosodic phrasing is provided from two sources: disfluencies, and ditropic cliticization, that is, the fact that grammatical pro clitics may be phonological en clit- ics (i.e. phrased with a preceding host), but grammatical enclitics are never phonological proclit- ics. Earlier explanations for the suffixing preference have neglected prosody almost completely and thus also missed the related asymmetry in ditropic cliticization. More importantly, the evi - dence from prosodic phrasing suggests a new venue for explaining the suffixing preference. The asymmetry in prosodic phrasing, which, according to the hypothesis proposed here, is a major fac - tor underlying the suffixing preference, has a natural basis in the mechanics of turn-taking as well as in the mechanics of speech production.* Keywords : affixes, clitics, language processing, turn-taking, grammaticization, explanation in ty - pology, Tagalog 1. -

Day 17: Possessive and Demonstrative Adjectives LESSON 17: Possessive and Demonstrative Adjectives

Day 17: Possessive and Demonstrative Adjectives LESSON 17: Possessive and Demonstrative Adjectives We all know what adjectives can do (right??) These are the words that describe a noun. But their purpose is not limited to descriptions such as cool or kind or pretty. They have a host of other uses like providing more information about the noun they’re appearing with or even pointing out something. In this lesson, we’ll be talking about (or rather, breezing through) possessive adjectives and demonstrative adjectives. These are relatively easy topics that won’t be needing a lot of brain cell activity. So sit back and try to enjoy today’s topic. First, possessive adjectives. When you need to express that a noun belongs to another person or thing, you use possessive adjectives. We know it in English as the words: my, your, his, her, its, our, and their. In French, the possessive adjectives (like all other kinds of adjectives) need to agree to the noun they’re describing. Here’s a nifty little table to cover all that. Track 45 When used with When used with When used with plural What it means masculine singular feminine singular noun noun whether feminine noun or masculine mon ma (*mon) mes my ton ta (*ton) tes your son sa (*son) ses his/her/its/one’s notre notre nos our votre votre vos your leur leur leurs their Note that *mon, ton and son are used in the feminine form with nouns that begin with a vowel or the letter h. Here are some more reminders in using possessive adjectives: • Possessive adjectives always come BEFORE the noun. -

6 the Major Parts of Speech

6 The Major Parts of Speech KEY CONCEPTS Parts of Speech Major Parts of Speech Nouns Verbs Adjectives Adverbs Appendix: prototypes INTRODUCTION In every language we find groups of words that share grammatical charac- teristics. These groups are called “parts of speech,” and we examine them in this chapter and the next. Though many writers onlanguage refer to “the eight parts of speech” (e.g., Weaver 1996: 254), the actual number of parts of speech we need to recognize in a language is determined by how fine- grained our analysis of the language is—the more fine-grained, the greater the number of parts of speech that will be distinguished. In this book we distinguish nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs (the major parts of speech), and pronouns, wh-words, articles, auxiliary verbs, prepositions, intensifiers, conjunctions, and particles (the minor parts of speech). Every literate person needs at least a minimal understanding of parts of speech in order to be able to use such commonplace items as diction- aries and thesauruses, which classify words according to their parts (and sub-parts) of speech. For example, the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, p. xxxi) distinguishes adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, definite ar- ticles, indefinite articles, interjections, nouns, prepositions, pronouns, and verbs. It also distinguishes transitive, intransitive, and auxiliary verbs. Writ- ers and writing teachers need to know about parts of speech in order to be able to use and teach about style manuals and school grammars. Regardless of their discipline, teachers need this information to be able to help students expand the contexts in which they can effectively communicate. -

The Impact of Function Words on the Processing and Acquisition of Syntax

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY The Impact of Function Words on the Processing and Acquisition of Syntax A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of Linguistics By Jessica Peterson Hicks EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2006 2 © Copyright by Jessica Peterson Hicks 2006 All Rights Reserved 3 ABSTRACT The Impact of Function Words on the Processing and Acquisition of Syntax Jessica Peterson Hicks This dissertation investigates the role of function words in syntactic processing by studying lexical retrieval in adults and novel word categorization in infants. Christophe and colleagues (1997, in press) found that function words help listeners quickly recognize a word and infer its syntactic category. Here, we show that function words also help listeners make strong on-line predictions about syntactic categories, speeding lexical access. Moreover, we show that infants use this predictive nature of function words to segment and categorize novel words. Two experiments tested whether determiners and auxiliaries could cause category- specific slowdowns in an adult word-spotting task. Adults identified targets faster in grammatical contexts, suggesting that a functor helps the listener construct a syntactic parse that affects the speed of word identification; also, a large prosodic break facilitated target access more than a smaller break. A third experiment measured independent semantic ratings of the stimuli used in Experiments 1 and 2, confirming that the observed grammaticality effect mainly reflects syntactic, and not semantic, processing. Next, two preferential-listening experiments show that by 15 months, infants use function words to infer the category of novel words and to better recognize those words in continuous speech. -

Hungarian Copula Constructions in Dependency Syntax and Parsing

Hungarian copula constructions in dependency syntax and parsing Katalin Ilona Simko´ Veronika Vincze University of Szeged University of Szeged Institute of Informatics Institute of Informatics Department of General Linguistics MTA-SZTE Hungary Research Group on Artificial Intelligence [email protected] Hungary [email protected] Abstract constructions? And if so, how can we deal with cases where the copula is not present in the sur- Copula constructions are problematic in face structure? the syntax of most languages. The paper In this paper, three different answers to these describes three different dependency syn- questions are discussed: the function head analy- tactic methods for handling copula con- sis, where function words, such as the copula, re- structions: function head, content head main the heads of the structures; the content head and complex label analysis. Furthermore, analysis, where the content words, in this case, the we also propose a POS-based approach to nominal part of the predicate, are the heads; and copula detection. We evaluate the impact the complex label analysis, where the copula re- of these approaches in computational pars- mains the head also, but the approach offers a dif- ing, in two parsing experiments for Hun- ferent solution to zero copulas. garian. First, we give a short description of Hungarian copula constructions. Second, the three depen- 1 Introduction dency syntactic frameworks are discussed in more Copula constructions show some special be- detail. Then, we describe two experiments aim- haviour in most human languages. In sentences ing to evaluate these frameworks in computational with copula constructions, the sentence’s predi- linguistics, specifically in dependency parsing for cate is not simply the main verb of the clause, Hungarian, similar to Nivre et al. -

Number and Adjectives : the Case of Activity and Quality Nominals Delphine Beauseroy, Marie-Laurence Knittel

Number and adjectives : the case of activity and quality nominals Delphine Beauseroy, Marie-Laurence Knittel To cite this version: Delphine Beauseroy, Marie-Laurence Knittel. Number and adjectives : the case of activity and quality nominals. 2012. hal-00418040v2 HAL Id: hal-00418040 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00418040v2 Preprint submitted on 11 Jun 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 NUMBER AND ADJECTIVES: THE CASE OF FRENCH ACTIVITY AND QUALITY NOMINALS 1. INTRODUCTION This article is dedicated to the examination of the role of Number with regards to adjective distribution in French. We focus on two kinds of abstract nouns: activity nominals and quality nominals. Both display particular behaviours with regards to adjective distribution: activity nominals need to appear as count nouns to be modified by qualifying adjectives; concerning quality nominals, they are frequently introduced by the indefinite un(e) instead of the partitive article (du / de la) when modified. Our analysis of adjectives is based on the idea that they can have two uses, which correlate with syntactic and semantic restrictions and are distinguishable on semantic grounds. Adjectives are understood either as taxonomic, i.e. -

Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1

Eun-Joo Kwak 55 Journal of Universal Language 15-2 September 2014, 55-76 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1 2 Eun-Joo Kwak Sejong University, Korea Abstract Countability and plurality (or singularity) are basically marked in syntax or morphology, and languages adopt different strategies in the mass-count distinction and number marking: plural marking, unmarked number marking, singularization, and different uses of classifiers. Diverse patterns of grammatical strategies are observed with cross-linguistic data in this study. Based on this, it is concluded that although countability is not solely determined by the semantic properties of nouns, it is much more affected by semantics than it appears. Moreover, semantic features of nouns are useful to account for apparent idiosyncratic behaviors of nouns and sentences. Keywords: countability, plurality, countability shift, individuation, animacy, classifier * This work is supported by the Sejong University Research Grant of 2013. Eun-Joo Kwak Department of English Language and Literature, Sejong University, Seoul, Korea Phone: +82-2-3408-3633; Email: [email protected] Received August 14, 2014; Revised September 3, 2014; Accepted September 10, 2014. 56 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability 1. Introduction The state of affairs in the real world may be delivered in a different way depending on the grammatical properties of languages. Nominal countability makes part of grammatical differences cross-linguistically, marked in various ways: plural (or singular) morphemes for nouns or verbs, distinct uses of determiners, and the occurrences of classifiers. Apparently, countability and plurality are mainly marked in syntax and morphology, so they may be understood as having less connection to the semantic features of nouns. -

Several Parts of Speech Nouns

What is a Part of Speech? A part of speech is a group of words that are used in a certain way. For example, "run," "jump," and "be" are all used to describe actions/states. Therefore they belong to the VERBS group. In other words, all words in the English language are divided into eight different categories. Each category has a different role/function in the sentence. The English parts of speech are: Nouns, pronouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, prepositions,conjunctions and interjections. Same Word – Several Parts of Speech In the English language many words are used in more than one way. This means that a word can function as several different parts of speech. For example, in the sentence "I would like a drink" the word "drink" is a noun. However, in the sentence "They drink too much" the word "drink" is a verb. So it all depends on the word's role in the sentence. Nouns A noun is a word that names a person, a place or a thing. Examples: Sarah, lady, cat, New York, Canada, room, school, football, reading. Example sentences: People like to go to the beach. Emma passed the test. My parents are traveling to Japan next month. The word "noun" comes from the Latin word nomen, which means "name," and nouns are indeed how we name people, places and things. Abstract Nouns An abstract noun is a noun that names an idea, not a physical thing. Examples: Hope, interest, love, peace, ability, success, knowledge, trouble. Concrete Nouns A concrete noun is a noun that names a physical thing.