3 Types of Anaphors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Syntax of the Malagasy Reciprocal Construction: an Lfg Account

THE SYNTAX OF THE MALAGASY RECIPROCAL CONSTRUCTION: AN LFG ACCOUNT Peter Hurst University of Melbourne Proceedings of the LFG06 Conference Universität Konstanz Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2006 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ ABSTRACT The verbal reciprocal construction in Malagasy is formed by a reciprocal morpheme prefixing on the main verb with a corresponding loss of an overt argument in c-structure. Analyses of similar constructions in Chichewa and Catalan both treat the reciprocalized verb's argument structure as undergoing an alteration whereby one of its thematic roles is either suppressed or two thematic arguments are mapped to one grammatical function. In this paper I propose that the reciprocal morpheme in Malagasy creates a reciprocal pronoun in f-structure - thus maintaining its valency and leaving the argument structure of the verb unchanged, while at the same time losing an argument at the level of c-structure. 1. INTRODUCTION Malagasy is an Austronesian language and is the dominant language of Madagascar. The Malagasy sentences used in the analysis below are from the literature - in particular from a paper by Keenan and Razafimamonjy (2001) titled “Reciprocals in Malagasy” whose examples are based on the official dialect of Malagasy as spoken in and around the capital city Antananarivo. The Malagasy reciprocal construction is formed by the addition of a prefix -if- or -ifamp- to the stem of the verb accompanied by the loss of an overt argument in object position. Compare sentence (1a) below with its reciprocated equivalent (1b): (1) Malagasy a. N-an-daka an-dRabe Rakoto pst-act-kick acc.Rabe Rakoto V O S 'Rakoto kicked Rabe' b. -

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

Givenness and Its Realization in a Linguistic and in a Non- Linguistic Environment

VILNIUS PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHILOLOGY NATALIJA ZACHAROVA GIVENNESS AND ITS REALIZATION IN A LINGUISTIC AND IN A NON- LINGUISTIC ENVIRONMENT MA Paper Academic advisor: prof. Dr. Hab. Laimutis Valeika Vilnius, 2008 VILNIUS PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHILOLOGY GIVENNESS AND ITS REALIZATION IN A LINGUISTIC AND IN A NON- LINGUISTIC ENVIRONMENT This MA paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of the MA in English Philology By Natalija Zacharova I declare that this study is my own and does not contain any unacknowledged work from any source. (Signature) (Date) Academic advisor: prof. Dr. Hab. Laimutis Valeika (Signature) (Date) Vilnius, 2008 2 CONTENTS ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………….4 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………...5 1. THE PROBLEMS OF THE INFORMATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE SENTENCE ……………………………………………………………….8 1.1. The sentence as dialectical entity of given and new……………………...8 1.2. Givenness vs. Newnness………………………………………………….11 1.3. The realization of Givenness……………………………………………..12 1.4. Givenness expressed by the definite article ……………………………..15 1.5. Givenness expressed by the indefinite article…………………………….19 1.6. Givenness expressed by semi-grammatical definite determiners and lexical determiners………………………………………………………..20 2. THE REALIZATION OF GIVENNESS IN A LINGUISTIC ENVIRONMENT……………………………………………………………………21 2.1. Anaphoric Givenness………………………………………………………22 2.2. Cataphoric Givenness……………………………………………………...29 2.3. Givenness expressed by the use of the indefinite article…………………..30 3. THE REALIZATION OF GIVENNESS IN A NON- LINGUISTIC ENVIRONMENT……………………………………………………………………..32 3. 1. The environment of the home……………………………………………...33 3.2. The environment of the town/country, world………………………………35 3.3. The environment of the universe…………………………………………....37 3.4. Cultural environment……………………………………………………….38 4. -

Cross-Dialectal Variability in Propositional Anaphora: a Quantitative and Pragmatic Study of Null Objects in Mexican and Peninsular Spanish

CROSS-DIALECTAL VARIABILITY IN PROPOSITIONAL ANAPHORA: A QUANTITATIVE AND PRAGMATIC STUDY OF NULL OBJECTS IN MEXICAN AND PENINSULAR SPANISH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Maria Asela Reig, PhD The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Professor Scott A. Schwenter, Adviser Approved by Professor Rebeka Campos-Astorkiza Professor Terrell Morgan Professor Rena Torres-Cacoullos ________________________ Adviser Graduate Program in Spanish and Portuguese ABSTRACT In this dissertation, I analyze the linguistic constraints that condition the variation in Spanish between the null pronoun and the clitic lo referring to a proposition. Previous literature on Spanish has analyzed null objects referring to first order entities, mostly in varieties in contact with other languages. This dissertation contributes to the literature on anaphora in Spanish by establishing and analyzing the existence of propositional null objects in two monolingual dialects, Mexican and Peninsular Spanish. A variationist approach was used to discover the significant constraints on the variation of the null pronoun and the overt clitic lo in Mexican and Peninsular Spanish. Following the generalizations from the previous literature on two separate areas of study, anaphora resolution and null objects (Chapter 2), several internal factor groups were included in the coding scheme. In Chapter 3, I provide an explicit statement of the envelope of variation and I specify the coding scheme employed. Chapter 4 offers the results of the multivariate analyses of Mexican and Peninsular Spanish. These results show that some of the linguistic constraints conditioning the variation are shared by both dialects (presence of a dative pronoun, type ii of antecedent, sentence type), suggesting that the null pronoun has the same grammatical role in both dialects. -

Show Business: Deixis in Fifth-Century Athenian Drama

Show Business: Deixis in Fifth-Century Athenian Drama by David Julius Jacobson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Donald Mastronarde Professor Leslie Kurke Professor Mary-Kay Gamel Professor Shannon Jackson Spring 2011 Show Business: Deixis in Fifth-Century Athenian Drama Copyright 2011 by David Julius Jacobson Abstract Show Business: Deixis in Fifth-Century Athenian Drama by David Julius Jacobson Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair In my dissertation I examine the use of deixis in fifth-century Athenian drama to show how a playwright’s lexical choices shape an audience’s engagement with and investment in a dramatic work. The study combines modern performance theories concerning the relationship between actor and audience with a detailed examination of the demonstratives ὅδε and οὗτος in a representative sample of tragedy (and satyr play) and in the full Aristophanic corpus, and reaches conclusions that aid and expand our understanding of both tragedy and comedy. In addition to exploring and interpreting a number of particular scenes for their inter-actor dynamics and staging, I argue overall that tragedy’s predilection for ὅδε , a word which by definition conveys a strong spatio- temporal presence (“this <one> here / now”), pointedly draws the spectators into the dramatic fiction. The comic poet’s preference for οὗτος (“that <one> just mentioned” / “that <one> there”), on the other hand, coupled with his tendency to directly acknowledge the audience individually and in the aggregate, disengages the spectators from the immediacy of the tragic tetralogies and reengages them with the normal, everyday world to which they will return at the close of the festival. -

Exophoric and Endophoric Awareness

Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Volume.8 Number3 September 2017 Pp. 28-45 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol8no3.3 Exophoric and Endophoric Awareness Mohammad Awwad Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences Lebanese University, Deanship Dekweneh , Beirut, Lebanon Abstract This research aims to shed light on the impact of exophoric and endophoric instruction on the comprehension (decoding) skills, writing (encoding skills), and linguistic awareness of English as Foreign Language learners. In this line, a mixed qualitative quantitative approach was conducted over a period of fifteen weeks on sixty English major students enrolled in their first year at the Lebanese University, fifth branch. The sixty participants were divided into two groups (30 experimental) that benefited from instruction on exophoric and endophoric relations and (30 control) that did not have the opportunity to study referents in the designated period of the research. The participants sat for a reading and writing pretest at the beginning of the study; and they sat again for the same reading and writing assessment at the end of the study. The results of the pre and post tests for both groups were analyzed via SPSS program and findings were as follows: hypothesis one stating that students who are aware of endophoric and exophoric relations are likely to achieve better results in decoding a text than are their peers who receive no referential instruction, was accepted with significant findings. Hypothesis two stating that students who are aware of endophoric and exophoric relations are likely to perform better in writing than their peers who receive no referential instruction , was accepted with significant findings. -

II Levels of Language

II Levels of language 1 Phonetics and phonology 1.1 Characterising articulations 1.1.1 Consonants 1.1.2 Vowels 1.2 Phonotactics 1.3 Syllable structure 1.4 Prosody 1.5 Writing and sound 2 Morphology 2.1 Word, morpheme and allomorph 2.1.1 Various types of morphemes 2.2 Word classes 2.3 Inflectional morphology 2.3.1 Other types of inflection 2.3.2 Status of inflectional morphology 2.4 Derivational morphology 2.4.1 Types of word formation 2.4.2 Further issues in word formation 2.4.3 The mixed lexicon 2.4.4 Phonological processes in word formation 3 Lexicology 3.1 Awareness of the lexicon 3.2 Terms and distinctions 3.3 Word fields 3.4 Lexicological processes in English 3.5 Questions of style 4 Syntax 4.1 The nature of linguistic theory 4.2 Why analyse sentence structure? 4.2.1 Acquisition of syntax 4.2.2 Sentence production 4.3 The structure of clauses and sentences 4.3.1 Form and function 4.3.2 Arguments and complements 4.3.3 Thematic roles in sentences 4.3.4 Traces 4.3.5 Empty categories 4.3.6 Similarities in patterning Raymond Hickey Levels of language Page 2 of 115 4.4 Sentence analysis 4.4.1 Phrase structure grammar 4.4.2 The concept of ‘generation’ 4.4.3 Surface ambiguity 4.4.4 Impossible sentences 4.5 The study of syntax 4.5.1 The early model of generative grammar 4.5.2 The standard theory 4.5.3 EST and REST 4.5.4 X-bar theory 4.5.5 Government and binding theory 4.5.6 Universal grammar 4.5.7 Modular organisation of language 4.5.8 The minimalist program 5 Semantics 5.1 The meaning of ‘meaning’ 5.1.1 Presupposition and entailment 5.2 -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

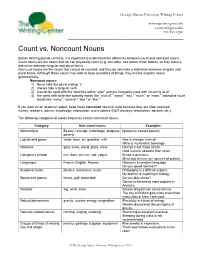

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Further Remarks on Reciprocal Constructions (To Appear In: Nedjalkov, Vladimir P

1 Further remarks on reciprocal constructions (to appear in: Nedjalkov, Vladimir P. (ed.) 2007. Reciprocal constructions. Amsterdam: Benjamins.) MARTIN HASPELMATH In view of the breathtaking scope of the comparative research enterprise led by Vladimir P. Nedjalkov whose results are published in these volumes, I have no choice but to select and highlight a few topics that I find particularly interesting and worthy of further comment and further study. I will focus here on conceptual and terminological issues and on some phenomena that have been discussed in the literature but are not so well represented in this work. I will also try to summarize some of the major known generalizations about reciprocals, as discussed in this work and elsewhere, in the form of twenty-six Greenberg-style numbered universals. 1. Reciprocal, mutual, symmetric Let us begin with a terminological discussion of the most basic term, reciprocal. In the present volumes, this term is used both for meanings (e.g. reciprocal situation, reciprocal event) and for forms (e.g. reciprocal construction, reciprocal marker, reciprocal predicate). In most cases, the context will disambiguate, but it seems to be a good idea to have two different terms for meanings and for forms, analogous to similar contrasts such as proposition/sentence, question/interrogative, participant/argument, time/tense, multiple/plural. Since all reciprocals express a situation with a mutual relation, I propose the term mutual for the semantic plane, reserving the term reciprocal for specialized expression patterns that code a mutual situation. A similar terminological distinction is made by König & Kokutani (2006), Evans (2007), Dimitriadis (2007), but these authors propose the term symmetric for meanings, reserving reciprocal for forms. -

Verbal Agreement with Collective Nominal Constructions: Syntactic and Semantic Determinants

ATLANTIS Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies 39.1 (June 2017): 33-54 issn 0210-6124 | e-issn 1989-6840 Verbal Agreement with Collective Nominal Constructions: Syntactic and Semantic Determinants Yolanda Fernández-Pena Universidade de Vigo [email protected] This corpus-based study investigates the patterns of verbal agreement of twenty-three singular collective nouns which take of-dependents (e.g., a group of boys, a set of points). The main goal is to explore the influence exerted by theof -PP on verb number. To this end, syntactic factors, such as the plural morphology of the oblique noun (i.e., the noun in the of- PP) and syntactic distance, as well as semantic issues, such as the animacy or humanness of the oblique noun within the of-PP, were analysed. The data show the strongly conditioning effect of plural of-dependents on the number of the verb: they favour a significant proportion of plural verbal forms. This preference for plural verbal patterns, however, diminishes considerably with increasing syntactic distance when the of-PP contains a non-overtly- marked plural noun such as people. The results for the semantic issues explored here indicate that animacy and humanness are also relevant factors as regards the high rate of plural agreement observed in these constructions. Keywords: agreement; collective; of-PP; distance; animacy; corpus . Concordancia verbal con construcciones nominales colectivas: sintaxis y semántica como factores determinantes Este estudio de corpus investiga los patrones de concordancia verbal de veintitrés nombres colectivos singulares que toman complementos seleccionados por la preposición of, como en los ejemplos a group of boys, a set of points. -

TRANSLATION PECULIARITIES of the PREPOSITIONS and Each of the Prepositional Phrases Has the Following Three Features: ADVERBS USED AS PARTICLES of PHRASAL VERBS 1

UNIVERSITATEA DE STUDII EUROPENE ANALELE ŞTIINŢIFICE UNIVERSITATEA DE STUDII EUROPENE ANALELE ŞTIINŢIFICE DIN MOLDOVA ISSN 2435-1114 DIN MOLDOVA ISSN 2435-1114 object. Prepositions may occur either before the word it governs or they may occupy a final position. The difficulties involved by the study of English prepositions are determined by their rich synonymy and poly functionalism: a) One single relation may be expressed by several prepositions differing ideographically or stylistically (for example the idea of residence – by, at, in, with, within, inside, etc). b) One single preposition may express several relations (for example by – relation of space, of time, of agency, of numerical distribution, etc) [5, p. 2]. Central members of the preposition class in English have the following properties: I. Formal invariability, in the sense that they show no inflectional variation; II. They take noun phrases or nominally-functioning clauses (and even other prepositional phrases) as complements; III. They display a variety of functions both at phrase level as well as the sentence level TRANSLATION PECULIARITIES OF THE PREPOSITIONS AND Each of the prepositional phrases has the following three features: ADVERBS USED AS PARTICLES OF PHRASAL VERBS 1. It has no modifier, even when the phrase contains a count noun; 2. The speaker is not free to use any preposition except the one given; Dorina BOICO 3. The meaning is fixed [3, p. 24]. magistru, lector universitar, USEM The fixed expression cannot normally be used: [email protected] a. If a modifier is added b. If a different preposition is used c. If a different meaning is intended Adverbs (etymology: Middle English adverbe, from Old French, from Latin adverbium Abstract: The present article represents a new try for establishing the resemblances and differences between (translation of Greek epirrh ma) : ad-, in relation to ; see ad- + verbum, word, verb; see wer- in prepositions, adverbs and phrasal verbs.