1 97. Count/Mass Distinctions Across Languages 1. Outline 2. Correlates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classifiers: a Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Modern & Classical Languages Humanities 3-2002 Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J. Vajda Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Vajda, Edward J., "Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization" (2002). Modern & Classical Languages. 35. https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs/35 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern & Classical Languages by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J. Linguistics38 (2002), I37-172. ? 2002 CambridgeUniversity Press Printedin the United Kingdom REVIEWS J. Linguistics 38 (2002). DOI: Io.IOI7/So022226702211378 ? 2002 Cambridge University Press Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, Classifiers: a typology of noun categorization devices.Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2000. Pp. xxvi+ 535. Reviewedby EDWARDJ. VAJDA,Western Washington University This book offers a multifaceted,cross-linguistic survey of all types of grammaticaldevices used to categorizenouns. It representsan ambitious expansion beyond earlier studies dealing with individual aspects of this phenomenon, notably Corbett's (I99I) landmark monograph on noun classes(genders), Dixon's importantessay (I982) distinguishingnoun classes fromclassifiers, and Greenberg's(I972) seminalpaper on numeralclassifiers. Aikhenvald'sClassifiers exceeds them all in the number of languages it examines and in its breadth of typological inquiry. The full gamut of morphologicalpatterns used to classify nouns (or, more accurately,the referentsof nouns)is consideredholistically, with an eye towardcategorizing the categorizationdevices themselvesin terms of a comprehensiveframe- work. -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

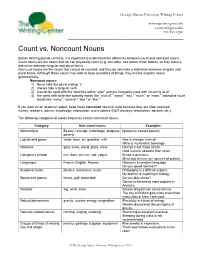

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

The “Person” Category in the Zamuco Languages. a Diachronic Perspective

On rare typological features of the Zamucoan languages, in the framework of the Chaco linguistic area Pier Marco Bertinetto Luca Ciucci Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa The Zamucoan family Ayoreo ca. 4500 speakers Old Zamuco (a.k.a. Ancient Zamuco) spoken in the XVIII century, extinct Chamacoco (Ɨbɨtoso, Tomarâho) ca. 1800 speakers The Zamucoan family The first stable contact with Zamucoan populations took place in the early 18th century in the reduction of San Ignacio de Samuco. The Jesuit Ignace Chomé wrote a grammar of Old Zamuco (Arte de la lengua zamuca). The Chamacoco established friendly relationships by the end of the 19th century. The Ayoreos surrended rather late (towards the middle of the last century); there are still a few nomadic small bands in Northern Paraguay. The Zamucoan family Main typological features -Fusional structure -Word order features: - SVO - Genitive+Noun - Noun + Adjective Zamucoan typologically rare features Nominal tripartition Radical tenselessness Nominal aspect Affix order in Chamacoco 3 plural Gender + classifiers 1 person ø-marking in Ayoreo realis Traces of conjunct / disjunct system in Old Zamuco Greater plural and clusivity Para-hypotaxis Nominal tripartition Radical tenselessness Nominal aspect Affix order in Chamacoco 3 plural Gender + classifiers 1 person ø-marking in Ayoreo realis Traces of conjunct / disjunct system in Old Zamuco Greater plural and clusivity Para-hypotaxis Nominal tripartition All Zamucoan languages present a morphological tripartition in their nominals. The base-form (BF) is typically used for predication. The singular-BF is (Ayoreo & Old Zamuco) or used to be (Cham.) the basis for any morphological operation. The full-form (FF) occurs in argumental position. -

Syntactic Variation in English Quantified Noun Phrases with All, Whole, Both and Half

Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Acta Wexionensia Nr 38/2004 Humaniora Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Maria Estling Vannestål Växjö University Press Abstract Estling Vannestål, Maria, 2004. Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half, Acta Wexionensia nr 38/2004. ISSN: 1404-4307, ISBN: 91-7636-406-2. Written in English. The overall aim of the present study is to investigate syntactic variation in certain Present-day English noun phrase types including the quantifiers all, whole, both and half (e.g. a half hour vs. half an hour). More specific research questions concerns the overall frequency distribution of the variants, how they are distrib- uted across regions and media and what linguistic factors influence the choice of variant. The study is based on corpus material comprising three newspapers from 1995 (The Independent, The New York Times and The Sydney Morning Herald) and two spoken corpora (the dialogue component of the BNC and the Longman Spoken American Corpus). The book presents a number of previously not discussed issues with respect to all, whole, both and half. The study of distribution shows that one form often predominated greatly over the other(s) and that there were several cases of re- gional variation. A number of linguistic factors further seem to be involved for each of the variables analysed, such as the syntactic function of the noun phrase and the presence of certain elements in the NP or its near co-text. -

Formal Semantics

HG2002 Semantics and Pragmatics Formal Semantics Francis Bond Division of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies http://www3.ntu.edu.sg/home/fcbond/ [email protected] Lecture 10 Location: HSS Auditorium Creative Commons Attribution License: you are free to share and adapt as long as you give appropriate credit and add no additional restrictions: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. HG2002 (2018) Overview ã Revision: Components ã Quantifiers and Higher Order Logic ã Modality ã (Dynamic Approaches to Discourse) ã Next Lecture: Chapter 11 — Cognitive Semantics HG2002 (2018) 1 Revision: Componential Analysis HG2002 (2018) 2 Break word meaning into its components ã components allow a compact description ã interact with morphology/syntax ã form part of our cognitive architecture ã For example: woman [female] [adult] [human] spinster [female] [adult] [human] [unmarried] bachelor [male] [adult] [human] [unmarried] wife [female] [adult] [human] [married] ã We can make things more economical (fewer components): woman [+female] [+adult] [+human] spinster [+female] [+adult] [+human] [–married] bachelor [–female] [+adult] [+human] [–married] wife [+female] [+adult] [+human] [+married] HG2002 (2018) 3 Defining Relations using Components ã hyponymy: P is a hyponym of Q if all the components of Q are also in P. spinster ⊂ woman; wife ⊂ woman ã incompatibility: P is incompatible with Q if they share some components but differ in one or more contrasting components spinster ̸≈ wife ã Redundancy Rules [+human] ! [+animate] [+animate] ! [+concrete] [+married] -

Double Classifiers in Navajo Verbs *

Double Classifiers in Navajo Verbs * Lauren Pronger Class of 2018 1 Introduction Navajo verbs contain a morpheme known as a “classifier”. The exact functions of these morphemes are not fully understood, although there are some hypotheses, listed in Sec- tions 2.1-2.3 and 4. While the l and ł-classifiers are thought to have an effect on averb’s transitivity, there does not seem to be a comparable function of the ; and d-classifiers. However, some sources do suggest that the d-classifier is associated with the middle voice (see Section 4). In addition to any hypothesized semantic functions, the d-classifier is also one of the two most common morphemes that trigger what is known as the d-effect, essentially a voicing alternation of the following consonant explained in Section 3 (the other mor- pheme is the 1st person dual plural marker ‘-iid-’). When the d-effect occurs, the ‘d’ of the involved morpheme is often realized as null in the surface verb. This means that the only evidence of most d-classifiers in a surface verb is the voicing alternation of the following stem-initial consonant from the d-effect. There is also a rare phenomenon where two *I would like to thank Jonathan Washington and Emily Gasser for providing helpful feedback on earlier versions of this thesis, and Jeremy Fahringer for his assistance in using the Swarthmore online Navajo dictionary. I would also like to thank Ted Fernald, Ellavina Perkins, and Irene Silentman for introducing me to the Navajo language. 1 classifiers occur in a single verb, something that shouldn’t be possible with position class morphology. -

1 Noun Classes and Classifiers, Semantics of Alexandra Y

1 Noun classes and classifiers, semantics of Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald Research Centre for Linguistic Typology, La Trobe University, Melbourne Abstract Almost all languages have some grammatical means for the linguistic categorization of noun referents. Noun categorization devices range from the lexical numeral classifiers of South-East Asia to the highly grammaticalized noun classes and genders in African and Indo-European languages. Further noun categorization devices include noun classifiers, classifiers in possessive constructions, verbal classifiers, and two rare types: locative and deictic classifiers. Classifiers and noun classes provide a unique insight into how the world is categorized through language in terms of universal semantic parameters involving humanness, animacy, sex, shape, form, consistency, orientation in space, and the functional properties of referents. ABBREVIATIONS: ABS - absolutive; CL - classifier; ERG - ergative; FEM - feminine; LOC – locative; MASC - masculine; SG – singular 2 KEY WORDS: noun classes, genders, classifiers, possessive constructions, shape, form, function, social status, metaphorical extension 3 Almost all languages have some grammatical means for the linguistic categorization of nouns and nominals. The continuum of noun categorization devices covers a range of devices from the lexical numeral classifiers of South-East Asia to the highly grammaticalized gender agreement classes of Indo-European languages. They have a similar semantic basis, and one can develop from the other. They provide a unique insight into how people categorize the world through their language in terms of universal semantic parameters involving humanness, animacy, sex, shape, form, consistency, and functional properties. Noun categorization devices are morphemes which occur in surface structures under specifiable conditions, and denote some salient perceived or imputed characteristics of the entity to which an associated noun refers (Allan 1977: 285). -

Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1

Eun-Joo Kwak 55 Journal of Universal Language 15-2 September 2014, 55-76 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1 2 Eun-Joo Kwak Sejong University, Korea Abstract Countability and plurality (or singularity) are basically marked in syntax or morphology, and languages adopt different strategies in the mass-count distinction and number marking: plural marking, unmarked number marking, singularization, and different uses of classifiers. Diverse patterns of grammatical strategies are observed with cross-linguistic data in this study. Based on this, it is concluded that although countability is not solely determined by the semantic properties of nouns, it is much more affected by semantics than it appears. Moreover, semantic features of nouns are useful to account for apparent idiosyncratic behaviors of nouns and sentences. Keywords: countability, plurality, countability shift, individuation, animacy, classifier * This work is supported by the Sejong University Research Grant of 2013. Eun-Joo Kwak Department of English Language and Literature, Sejong University, Seoul, Korea Phone: +82-2-3408-3633; Email: [email protected] Received August 14, 2014; Revised September 3, 2014; Accepted September 10, 2014. 56 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability 1. Introduction The state of affairs in the real world may be delivered in a different way depending on the grammatical properties of languages. Nominal countability makes part of grammatical differences cross-linguistically, marked in various ways: plural (or singular) morphemes for nouns or verbs, distinct uses of determiners, and the occurrences of classifiers. Apparently, countability and plurality are mainly marked in syntax and morphology, so they may be understood as having less connection to the semantic features of nouns. -

Nominal Aspect in the Romance Infinitives

Nominal Aspect in the Romance Infinitives Monica Palmerini Among the parts-of-speech, a special position is occupied by the infinitive, a grammatical category which has generated a rich debate and a vast literature. In this paper we would like to propose a semantic analysis of this subtype of part-of-speech, halfway between a verb and a noun, based on the notion of Nominal Aspect proposed by Rijkhoff (1991, 2002). To capture in a systematic way the crosslinguistic variability in the types of interpretations available to nouns, Rijkhoff proposed the concept of Nominal Aspect as a nominal counterpart of the way verbal aspect encapsulates the way actions and events are conceptualized. He individuated two dimensions of variation, namely divisibility in space and boundedness, dealing with the way referents are formed in the dimension of space. Encoded by the two binary features [±structure] and [±shape], these parameters define four lexical kinds of nouns. (1) + structure +shape collective nouns + structure -shape mass nouns - structure +shape individual nouns - structure - shape concept nouns We argue that the infinitive, as it appears in romance languages such as Spanish and Italian, can be said to match very closely the aspectual profile of the so called concept nouns, those that, typically in classifier languages, refer to “atoms of meaning” (types) that only in discourse become actualized lexemes: similarly, in abstraction from the context, the infinitive is neither a verb nor a noun. If we consider that the first order noun, the default nominal model in the majority of Indo-european languages has the aspect of an individual noun, the infinitive appear to be, as Sechehaye noticed (1950: 169), an original and innovative lexical resource, which displays in the grammatical system of the romance languages a great variety of uses (Hernanz 1999; Skytte 1983). -

Automatic Acquisition of Subcategorization Frames from Untagged Text

AUTOMATIC ACQUISITION OF SUBCATEGORIZATION FRAMES FROM UNTAGGED TEXT Michael R. Brent MIT AI Lab 545 Technology Square Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 [email protected] ABSTRACT Journal (kindly provided by the Penn Tree Bank This paper describes an implemented program project). On this corpus, it makes 5101 observa- that takes a raw, untagged text corpus as its tions about 2258 orthographically distinct verbs. only input (no open-class dictionary) and gener- False positive rates vary from one to three percent ates a partial list of verbs occurring in the text of observations, depending on the SF. and the subcategorization frames (SFs) in which 1.1 WHY IT MATTERS they occur. Verbs are detected by a novel tech- nique based on the Case Filter of Rouvret and Accurate parsing requires knowing the sub- Vergnaud (1980). The completeness of the output categorization frames of verbs, as shown by (1). list increases monotonically with the total number (1) a. I expected [nv the man who smoked NP] of occurrences of each verb in the corpus. False to eat ice-cream positive rates are one to three percent of observa- h. I doubted [NP the man who liked to eat tions. Five SFs are currently detected and more ice-cream NP] are planned. Ultimately, I expect to provide a large SF dictionary to the NLP community and to Current high-coverage parsers tend to use either train dictionaries for specific corpora. custom, hand-generated lists of subcategorization frames (e.g., Hindle, 1983), or published, hand- 1 INTRODUCTION generated lists like the Ozford Advanced Learner's Dictionary of Contemporary English, Hornby and This paper describes an implemented program Covey (1973) (e.g., DeMarcken, 1990). -

3 Types of Anaphors

3 Types of anaphors Moving from the definition and characteristics of anaphors to the types of ana- phors, this chapter will detail the nomenclature of anaphor types established for this book. In general, anaphors can be categorised according to: their form; the type of relationship to their antecedent; the form of their antecedents; the position of anaphors and antecedents, i.e. intrasentential or intersentential; and other features (cf. Mitkov 2002: 8-17). The procedure adopted here is to catego- rise anaphors according to their form. It should be stressed that the types dis- tinguished in this book are not universal categories, so the proposed classifica- tion is not the only possible solution. For instance, personal, possessive and re- flexive pronouns can be seen as three types or as one type. With the latter, the three pronoun classes are subsumed under the term “central pronouns”, as it is adopted here. Linguistic classifications of anaphors can be found in two established gram- mar books, namely in Quirk et al.’s A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language (2012: 865) and in The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (Stirling & Huddleston 2010: 1449-1564). Quirk et al. include a chapter of pro- forms and here distinguish between coreference and substitution. However, they do not take anaphors as their starting point of categorisation. Additionally, Stirling & Huddleston do not consider anaphors on their own but together with deixis. As a result, anaphoric noun phrases with a definite article, for example, are not included in both categorisations. Furthermore, Schubert (2012: 31-55) presents a text-linguistic view, of which anaphors are part, but his classification is similarly unsuitable because it does not focus on the anaphoric items specifi- cally.