Articles and Nouns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

Classifiers: a Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Modern & Classical Languages Humanities 3-2002 Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J. Vajda Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Vajda, Edward J., "Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization" (2002). Modern & Classical Languages. 35. https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs/35 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern & Classical Languages by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J. Linguistics38 (2002), I37-172. ? 2002 CambridgeUniversity Press Printedin the United Kingdom REVIEWS J. Linguistics 38 (2002). DOI: Io.IOI7/So022226702211378 ? 2002 Cambridge University Press Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, Classifiers: a typology of noun categorization devices.Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2000. Pp. xxvi+ 535. Reviewedby EDWARDJ. VAJDA,Western Washington University This book offers a multifaceted,cross-linguistic survey of all types of grammaticaldevices used to categorizenouns. It representsan ambitious expansion beyond earlier studies dealing with individual aspects of this phenomenon, notably Corbett's (I99I) landmark monograph on noun classes(genders), Dixon's importantessay (I982) distinguishingnoun classes fromclassifiers, and Greenberg's(I972) seminalpaper on numeralclassifiers. Aikhenvald'sClassifiers exceeds them all in the number of languages it examines and in its breadth of typological inquiry. The full gamut of morphologicalpatterns used to classify nouns (or, more accurately,the referentsof nouns)is consideredholistically, with an eye towardcategorizing the categorizationdevices themselvesin terms of a comprehensiveframe- work. -

Nouns, Adjectives, Verbs, and Adverbs

Unit 1: The Parts of Speech Noun—a person, place, thing, or idea Name: Person: boy Kate mom Place: house Minnesota ocean Adverbs—describe verbs, adjectives, and other Thing: car desk phone adverbs Idea: freedom prejudice sadness --------------------------------------------------------------- Answers the questions how, when, where, and to Pronoun—a word that takes the place of a noun. what extent Instead of… Kate – she car – it Many words ending in “ly” are adverbs: quickly, smoothly, truly A few other pronouns: he, they, I, you, we, them, who, everyone, anybody, that, many, both, few A few other adverbs: yesterday, ever, rather, quite, earlier --------------------------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------------------------- Adjective—describes a noun or pronoun Prepositions—show the relationship between a noun or pronoun and another word in the sentence. Answers the questions what kind, which one, how They begin a prepositional phrase, which has a many, and how much noun or pronoun after it, called the object. Articles are a sub category of adjectives and include Think of the box (things you have do to a box). the following three words: a, an, the Some prepositions: over, under, on, from, of, at, old car (what kind) that car (which one) two cars (how many) through, in, next to, against, like --------------------------------------------------------------- Conjunctions—connecting words. --------------------------------------------------------------- Connect ideas and/or sentence parts. Verb—action, condition, or state of being FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) Action (things you can do)—think, run, jump, climb, eat, grow A few other conjunctions are found at the beginning of a sentence: however, while, since, because Linking (or helping)—am, is, are, was, were --------------------------------------------------------------- Interjections—show emotion. -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

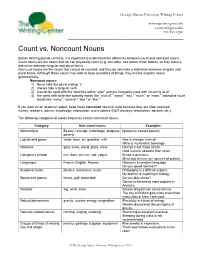

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Personal Pronouns, Pronoun-Antecedent Agreement, and Vague Or Unclear Pronoun References

Personal Pronouns, Pronoun-Antecedent Agreement, and Vague or Unclear Pronoun References PERSONAL PRONOUNS Personal pronouns are pronouns that are used to refer to specific individuals or things. Personal pronouns can be singular or plural, and can refer to someone in the first, second, or third person. First person is used when the speaker or narrator is identifying himself or herself. Second person is used when the speaker or narrator is directly addressing another person who is present. Third person is used when the speaker or narrator is referring to a person who is not present or to anything other than a person, e.g., a boat, a university, a theory. First-, second-, and third-person personal pronouns can all be singular or plural. Also, all of them can be nominative (the subject of a verb), objective (the object of a verb or preposition), or possessive. Personal pronouns tend to change form as they change number and function. Singular Plural 1st person I, me, my, mine We, us, our, ours 2nd person you, you, your, yours you, you, your, yours she, her, her, hers 3rd person he, him, his, his they, them, their, theirs it, it, its Most academic writing uses third-person personal pronouns exclusively and avoids first- and second-person personal pronouns. MORE . PRONOUN-ANTECEDENT AGREEMENT A personal pronoun takes the place of a noun. An antecedent is the word, phrase, or clause to which a pronoun refers. In all of the following examples, the antecedent is in bold and the pronoun is italicized: The teacher forgot her book. -

Politeness in Pronouns Third-Person Reference in Byzantine Documentary Papyri

Politeness in pronouns Third-person reference in Byzantine documentary papyri Klaas Bentein Ghent University/University of Michigan 1. Introduction: the T-V distinction In many languages, a person can be addressed in the second person singular or plural:1 the former indicates familiarity and/or lack of respect , while the latter suggests distance and/or respect towards the addressee.2 Consider, for example, the following two French sentences: (1) Tu ne peux pas faire ça! (2) Est-ce que vous voulez manger quelque chose? The first sentence could be uttered in an informal context, e.g. by a mother to her son, while the second could be uttered in a more formal context, e.g. by a student to his supervisor. In the literature, this distinction is known as the T-V distinction (Brown & Gilman 1960),3 referring to the Latin pronouns tu and vos .4 It is considered a ‘politeness strategy’ (Brown & Levinson 1987, 198-206). In Ancient Greek texts, such a distinction does not appear to be common (Zilliacus 1953, 5). 5 Consider, for example, the following petition: (3) ἐπεὶ οὖν], κύριε, καὶ οἱ διʼ [ἐναντίας ἐνταῦ]θα κατῆλθαν ἀξιῶ καὶ δέομαι ὅπως [κελεύσῃς ἱ]κανὰ [αὐ]τοὺς π[αρασχεῖν ἐν]ταῦθα ὀντων ⟦καὶ⟧ ἢ παραγγελῆναι αὐτοὺ[ς διὰ τῆς σῆς τ]άξεως πρὸς [τὸ] προσεδρευιν αὐτοὺς τῷ ἀχράντῳ σ[ο]υ δικασ[τηρίῳ ἵνα τῆ]ς δίκης λε[γομένης] μηδὲν ἐμπόδιον γένηται, καὶ τούτ[ου τυχόντα δι]ὰ παντός [σ]οι [χάριτας][ομολο]γῖν (P.Cair.Isid.66, ll. 19-24; 299 AD) “Since, then, my lord, my opponents in the case have also come down here, I request and beseech you to command that they furnish security while they are here or be instructed through your office to remain in attendance on your immaculate court, so that there may 1 My work was funded by the Belgian American Educational Foundation and the Flemish Fund for Scientific Research . -

Greek Grammar Review

Greek Study Guide Some Step-by-Step Translation Issues I. Part of Speech: Identify a word’s part of speech (noun, pronoun, adjective, verb, adverb, preposition, conjunction, particle, other) and basic dictionary form. II. Dealing with Nouns and Related Forms (Pronouns, Adjectives, Definite Article, Participles1) A. Decline the Noun or Related Form 1. Gender: Masculine, Feminine, or Neuter 2. Number: Singular or Plural 3. Case: Nominative, Genitive, Dative, Accusative, or Vocative B. Determine the Use of the Case for Nouns, Pronouns, or Substantives. (Part of examining larger syntactical unit of sentence or clause) C. Identify the antecedent of Pronouns and the referent of Adjectives and Participles. 1. Pronouns will agree with their antecedent in gender and number, but not necessarily case. 2. Adjectives/participles will agree with their referent in gender, number, and case (but will not necessary have the same endings). III. Dealing with Verbs (to include Infinitives and Participles) A. Parse the Verb 1. Tense/Aspect: Primary tenses: Present, Future, Perfect Secondary (past time) tenses: Imperfect, Aorist, Pluperfect 2. Mood: Moods: Indicative, Subjunctive, Imperative, or Optative Verbals: Infinitive or Participle [not technically moods] 3. Voice: Active, Middle, or Passive 4. Person: 1, 2, or 3. 5. Number: Singular or Plural Note: Infinitives do not have Person or Number; Participles do not have Person, but instead have Gender and Case (as do nouns and adjectives). B. Review uses of Infinitives, Participles, Subjunctives, Imperatives, and Optatives before translating these. C. Review aspect before translating any verb form. · See p. 60 in FGG (3rd and 4th editions) to translate imperfects and all present forms. -

Names a Person, Place, Thing, Or an Idea. A. Common Noun – Names Any One of a Group of Persons, Places, Things, Or Ideas

Name: __________________________________________ Block: ______ English II: Price 1. Noun – names a person, place, thing, or an idea. a. Common noun – names any one of a group of persons, places, things, or ideas. b. Proper noun – names a particular person, place, thing, or idea. c. Compound noun – consists of two or more words that together name a person, place, thing, or idea. d. Concrete noun – names a person, place, thing that can be perceived by one or more of the senses. e. Abstract noun – names an idea, a feeling, a quality, or a characteristic. f. Collective noun – names a group of people, animals, or things. 2. Pronoun – takes the place of one or more nouns or pronouns. a. Antecedent – the word or word group that a pronoun stands for. b. Personal pronouns – refers to the one(s) speaking (first person), the one(s) spoken to (second person), or the one(s) spoken about (third person). Singular Plural First person I, me, my, mine We, us, our, ours Second person You, your, yours You, your, yours Third person He, him, his, she, her, hers, it, its They, them, their, theirs c. Case Forms of Personal Pronouns – form that a pronoun takes to show its relationship to other words in a sentence. Case Forms of Personal Pronouns Nominative Case Objective Case Possessive Case Singular Plural Singular Plural Singular Plural First Person I We Me Us My, mine Our, ours Second Person You You You You Your, yours Your, yours Third Person He, she, it they Him her it them His, her, hers, its Their, theirs d. -

The Regularization of Old English Weak Verbs

Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas Vol. 10 año 2015, 78-89 EISSN 1886-6298 http://dx.doi.org/10.4995/rlyla.2015.3583 THE REGULARIZATION OF OLD ENGLISH WEAK VERBS Marta Tío Sáenz University of La Rioja Abstract: This article deals with the regularization of non-standard spellings of the verbal forms extracted from a corpus. It addresses the question of what the limits of regularization are when lemmatizing Old English weak verbs. The purpose of such regularization, also known as normalization, is to carry out lexicological analysis or lexicographical work. The analysis concentrates on weak verbs from the second class and draws on the lexical database of Old English Nerthus, which has incorporated the texts of the Dictionary of Old English Corpus. As regards the question of the limits of normalization, the solutions adopted are, in the first place, that when it is necessary to regularize, normalization is restricted to correspondences based on dialectal and diachronic variation and, secondly, that normalization has to be unidirectional. Keywords: Old English, regularization, normalization, lemmatization, weak verbs, lexical database Nerthus. 1. AIMS OF RESEARCH The aim of this research is to propose criteria that limit the process of normalization necessary to regularize the lemmata of Old English weak verbs from the second class. In general, lemmatization based on the textual forms provided by a corpus is a necessary step in lexicological analysis or lexicographical work. In the specific area of Old English studies, there are several reasons why it is important to compile a list of verbal lemmata. To begin with, the standard dictionaries of Old English, including An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary and The student’s Dictionary of Anglo-Saxon are complete although they are not based on an extensive corpus of the language but on the partial list of sources given in the prefaces or introductions to these dictionaries. -

Syntactic Variation in English Quantified Noun Phrases with All, Whole, Both and Half

Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Acta Wexionensia Nr 38/2004 Humaniora Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Maria Estling Vannestål Växjö University Press Abstract Estling Vannestål, Maria, 2004. Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half, Acta Wexionensia nr 38/2004. ISSN: 1404-4307, ISBN: 91-7636-406-2. Written in English. The overall aim of the present study is to investigate syntactic variation in certain Present-day English noun phrase types including the quantifiers all, whole, both and half (e.g. a half hour vs. half an hour). More specific research questions concerns the overall frequency distribution of the variants, how they are distrib- uted across regions and media and what linguistic factors influence the choice of variant. The study is based on corpus material comprising three newspapers from 1995 (The Independent, The New York Times and The Sydney Morning Herald) and two spoken corpora (the dialogue component of the BNC and the Longman Spoken American Corpus). The book presents a number of previously not discussed issues with respect to all, whole, both and half. The study of distribution shows that one form often predominated greatly over the other(s) and that there were several cases of re- gional variation. A number of linguistic factors further seem to be involved for each of the variables analysed, such as the syntactic function of the noun phrase and the presence of certain elements in the NP or its near co-text. -

PARTS of SPEECH ADJECTIVE: Describes a Noun Or Pronoun; Tells

PARTS OF SPEECH ADJECTIVE: Describes a noun or pronoun; tells which one, what kind or how many. ADVERB: Describes verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs; tells how, why, when, where, to what extent. CONJUNCTION: A word that joins two or more structures; may be coordinating, subordinating, or correlative. INTERJECTION: A word, usually at the beginning of a sentence, which is used to show emotion: one expressing strong emotion is followed by an exclamation point (!); mild emotion followed by a comma (,). NOUN: Name of a person, place, or thing (tells who or what); may be concrete or abstract; common or proper, singular or plural. PREPOSITION: A word that connects a noun or noun phrase (the object) to another word, phrase, or clause and conveys a relation between the elements. PRONOUN: Takes the place of a person, place, or thing: can function any way a noun can function; may be nominative, objective, or possessive; may be singular or plural; may be personal (therefore, first, second or third person), demonstrative, intensive, interrogative, reflexive, relative, or indefinite. VERB: Word that represents an action or a state of being; may be action, linking, or helping; may be past, present, or future tense; may be singular or plural; may have active or passive voice; may be indicative, imperative, or subjunctive mood. FUNCTIONS OF WORDS WITHIN A SENTENCE: CLAUSE: A group of words that contains a subject and complete predicate: may be independent (able to stand alone as a simple sentence) or dependent (unable to stand alone, not expressing a complete thought, acting as either a noun, adjective, or adverb).