A'ingae (Cofán/Kofán) Operators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfect-Traj.Pdf

Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change1 Cleo Condoravdi and Ashwini Deo Abstract: The grammaticalization literature notes the cross-linguistic robustness of a diachronic pat- tern involving the aspectual categories resultative, perfect, and perfective. Resultative aspect markers often develop into perfect markers, which then end up as perfect plus perfective markers. We intro- duce supporting data from the history of Old and Middle Indo-Aryan languages, whose instantiation of this pattern has not been previously noted. We provide a semantic analysis of the resultative, the perfect, and the aspectual category that combines perfect and perfective. Our analysis reveals the change to be a two-step generalization (semantic weakening) from the original resultative meaning. 1 Introduction The emergence of new functional expressions and the changes in their distribution and interpretation over time have been shown to be systematic across languages, as well as across a variety of semantic domains. These observations have led scholars to construe such changes in terms of “clines”, or predetermined trajectories, along which expressions move in time. Specifically, the typological literature, based on large-scale grammaticaliza- tion studies, has discovered several such trajectorial shifts in the domain of tense, aspect, and modality. Three properties characterize such shifts: (a) the categories involved are sta- ble across cross-linguistic instantiations; (b) the paths of change are unidirectional; (c) the shifts are uniformly generalizing (Heine, Claudi, and H¨unnemeyer 1991; Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Haspelmath 1999; Dahl 2000; Traugott and Dasher 2002; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Kiparsky 2012). A well-known trajectory is the one in (1). -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Aktionsart and Aspect in Qiang

The 2005 International Course and Conference on RRG, Academia Sinica, Taipei, June 26-30 AKTIONSART AND ASPECT IN QIANG Huang Chenglong Institute of Ethnology & Anthropology Chinese Academy of Social Sciences E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Qiang language reflects a basic Aktionsart dichotomy in the classification of stative and active verbs, the form of verbs directly reflects the elements of the lexical decomposition. Generally, State or activity is the basic form of the verb, which becomes an achievement or accomplishment when it takes a directional prefix, and becomes a causative achievement or causative accomplishment when it takes the causative suffix. It shows that grammatical aspect and Aktionsart seem to play much of a systematic role. Semantically, on the one hand, there is a clear-cut boundary between states and activities, but morphologically, however, there is no distinction between them. Both of them take the same marking to encode lexical aspect (Aktionsart), and grammatical aspect does not entirely correspond with lexical aspect. 1.0. Introduction The Ronghong variety of Qiang is spoken in Yadu Township (雅都鄉), Mao County (茂縣), Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture (阿壩藏族羌族自治州), Sichuan Province (四川省), China. It has more than 3,000 speakers. The Ronghong variety of Qiang belongs to the Yadu subdialect (雅都土語) of the Northern dialect of Qiang (羌語北部方言). It is mutually intelligible with other subdialects within the Northern dialect, but mutually unintelligible with other subdialects within the Southern dialect. In this paper we use Aktionsart and lexical decomposition, as developed by Van Valin and LaPolla (1997, Ch. 3 and Ch. 4), to discuss lexical aspect, grammatical aspect and the relationship between them in Qiang. -

Corpus Study of Tense, Aspect, and Modality in Diglossic Speech in Cairene Arabic

CORPUS STUDY OF TENSE, ASPECT, AND MODALITY IN DIGLOSSIC SPEECH IN CAIRENE ARABIC BY OLA AHMED MOSHREF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Elabbas Benmamoun, Chair Professor Eyamba Bokamba Professor Rakesh M. Bhatt Assistant Professor Marina Terkourafi ABSTRACT Morpho-syntactic features of Modern Standard Arabic mix intricately with those of Egyptian Colloquial Arabic in ordinary speech. I study the lexical, phonological and syntactic features of verb phrase morphemes and constituents in different tenses, aspects, moods. A corpus of over 3000 phrases was collected from religious, political/economic and sports interviews on four Egyptian satellite TV channels. The computational analysis of the data shows that systematic and content morphemes from both varieties of Arabic combine in principled ways. Syntactic considerations play a critical role with regard to the frequency and direction of code-switching between the negative marker, subject, or complement on one hand and the verb on the other. Morph-syntactic constraints regulate different types of discourse but more formal topics may exhibit more mixing between Colloquial aspect or future markers and Standard verbs. ii To the One Arab Dream that will come true inshaa’ Allah! عربية أنا.. أميت دمها خري الدماء.. كما يقول أيب الشاعر العراقي: بدر شاكر السياب Arab I am.. My nation’s blood is the finest.. As my father says Iraqi Poet: Badr Shaker Elsayyab iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I’m sincerely thankful to my advisor Prof. Elabbas Benmamoun, who during the six years of my study at UIUC was always kind, caring and supportive on the personal and academic levels. -

Aspectual Forms in Lutsotso

Languages Research Journal in Modern Languages and Literatures https://royalliteglobal.com/languages-and-literatures & Literatures Research Article Section: Literature, Languages and Criticism This article is published Aspectual forms in Lutsotso by Royallite Global, Kenya in the Research Journal in Modern Languages and Hellen Odera¹ & David Barasa² Literatures, Volume 2, Issue ¹-²Department of Languages and Literature Education, 2, 2021 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya Article Information Correspondence: [email protected] Submitted: 15th Jan 2021 Accepted: 30th Mar 2021 Published: 5th April 2021 Abstract This paper analyses the inflectional category of aspect in Additional information is Lutsotso, a dialect of the Oluluhya macro-language. Using available at the end of the descriptive approach, the paper establishes that there are article a number of inflectional morphemes affixed on the verb https://creativecommons. root to express, e.g. person, number, tense, aspect and org/licenses/by/4.0/ mood. Among these affixes, tense and aspect categories interact largely, hence, it is difficult to study one category To read the paper without referring to the other. While tense and aspect are online, please scan this profoundly connected in Lutsotso, this paper only identifies QR code and describes the inflectional form of aspect. Generally, aspect in Lutsotso relates to the grammatical viewpoints such as the perfective, imperfective and iterative forms. This includes the temporal properties of situations and the situation types as well. Aspect just like other grammatical categories such as tense, mood, person, agreement and number are important in understanding the grammar of Lutsotso. Keywords: aspect, Bantu, Lutsotso verb How to Cite: Public Interest Statement Odera, H., & Barasa, D. -

The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor

THE GRAMMAR OF FEAR: MORPHOSYNTACTIC METAPHOR IN FEAR CONSTRUCTIONS by HOLLY A. LAKEY A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Holly A. Lakey Title: The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor in Fear Constructions This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Linguistics by: Dr. Cynthia Vakareliyska Chairperson Dr. Scott DeLancey Core Member Dr. Eric Pederson Core Member Dr. Zhuo Jing-Schmidt Institutional Representative and Dr. Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2016. ii © 2016 Holly A. Lakey iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Holly A. Lakey Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics March 2016 Title: The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor in Fear Constructions This analysis explores the reflection of semantic features of emotion verbs that are metaphorized on the morphosyntactic level in constructions that express these emotions. This dissertation shows how the avoidance or distancing response to fear is mirrored in the morphosyntax of fear constructions (FCs) in certain Indo-European languages through the use of non-canonical grammatical markers. This analysis looks at both simple FCs consisting of a single clause and complex FCs, which feature a subordinate clause that acts as a complement to the fear verb in the main clause. In simple FCs in some highly-inflected Indo-European languages, the complement of the fear verb (which represents the fear source) is case-marked not accusative but genitive (Baltic and Slavic languages, Sanskrit, Anglo-Saxon) or ablative (Armenian, Sanskrit, Old Persian). -

The Semantics of Progressive Aspect: a Thorough Study MOUSUME AKHTER FLORA & S.M

The Semantics of Progressive Aspect: A Thorough Study MOUSUME AKHTER FLORA & S.M. MOHIBUL HASAN Abstract In English grammar, verbs have two important characteristics--tense and aspect. Grammatically tense is marked in two ways: Present and Past. English verbs can have another property called aspect, applicable in both present and past forms of verbs. There are two major types of morphologically marked aspects in English verbs: progressive and perfective. While present and past tenses are morphologically marked by the forms verb+s/es (as in He plays) and verb+d/ed (as in He played) respectively, the morphological representations of progressive and perfective aspects in the tenses are verb+ing (He is/was playing) and verb+d/ed/n/en (He has/had played) respectively. This paper focuses only on one type of aspectual feature of verbs--present progressive. It analyses the use of present progressive in terms of semantics and explains its use in different contexts for durative conclusive and non-conclusive use, for its use in relation to time of reference, and for its use in some special cases. Then it considers the restrictions on the use of progressive aspect in both present and past tenses based on the nature of verbs and duration of time. 1. Introduction ‘Aspect’ has been widely discussed in English grammar with respect to the internal structure of actions, states and events as it revolves around the grammatical category of English verb groups and tenses. Depending on the interpretations of actions, states, and events as a feature of the verbs or as a matter of speaker’s viewpoint, two approaches are available for aspect: ‘Temporal’ and ‘Non-temporal’. -

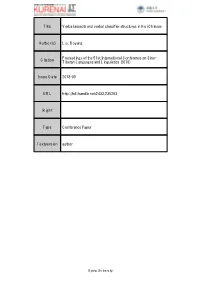

Title Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese

Title Verbal aspects and verbal classifier structures in Hui Chinese Author(s) Liu, Boyang Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235293 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese LIU Boyang (EHESS-CRLAO) CONTENT • PART I: Research Purpose • PART II: The definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 1. An introduction to Hui Chinese – 2. Previous work on VCLs in Mandarin – 3. A provisional definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 4. Lexical aspects indicated by the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP] in Sinitic languages – 5. Relationships between grammatical aspects and the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP- OBJECT] • PART III: Grammatical aspects indicated by special auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures in Hui Chinese – 6. The perfective aspect – 7. The imperfective aspect • PART IV: Conclusion PART I: RESEARCH PURPOSE Research Purpose: • Verbal classifiers (VCLs) have been much less studied from a typological perspective than the category of nominal classifiers (NCLs), and even less in the non-Mandarin branches of Sinitic languages, such as the Hui dialects; • In this study, I will introduce relationships between lexical aspects, grammatical aspects and verbal classifier phrases (VCLPs) in Hui Chinese, analyzing the similarities and differences with Standard Mandarin. • Verbal classifier structures in the Hui dialects display a transitional feature compared with Xiang, Gan and Wu, taking auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures as examples (auto-VCLs derive from verb reduplicants in the verb phrase [VERB- (‘one’)-VERB]): – Auto-VCLs in the verb phrase [VERB-AUTO VCL] can code the perfective or imperfective aspect in different types of complex sentences in Hui Chinese; – More variety of auto-VCL structures is found in Hui Chinese compared with Xiang and Gan dialects. -

'The System of Tense and Aspect in the Bantik Language'

The System of Tense and Aspect in the Bantik Language UTSUMI Atsuko Meisei University, Tokyo Japan The Bantik language, which belongs to the Sangiric micro-group (cf. Sneddon 1993) within the Philippine group, has two morphologically indicated tense oppositions—the non-past tense and the past tense. In addition, the language includes progressive, habitual, and iterative aspects. This paper aims, first, to present an overview of the tense and aspect systems in the Bantik language. Although Philippine languages are normally described as not having tenses but, rather, as having aspect, a group of Bantik verbs seem to show a tense opposition. Second, it focuses on the classification of Bantik verbs with respect to the meanings they express by their tense forms. In short, stative verbs express a current event by using the non-past tense, while achievement verbs express a future event with the non-past tense. Activity verbs are categorized into two groups; the first group uses the non-past tense to express a current event, while the second group expresses a future event. Abilitative verbs, in contrast to the other verbs, use the non-past form to refer to a past event. 1. Overview of Bantik Morphology concerning tense and aspect 1.1 Overview of tense and aspect in Philippine type languages In much of the literature on the Philippine type languages which are found across the Philippines and from North to Central Sulawesi, verbs are described as having aspect, but not tense. Most of those languages are claimed to have moods as well. For example, Himmelmann (2005:363) shows that the Tagalog verb paradigm has both a perfective/imperfective aspect opposition and a non-realis/realis mood opposition. -

Shǐxīng, a Sino-Tibetan Language

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 32.1 — April 2009 , A SINO-TIBETAN LANGUAGE OF SOUTH-WEST CHINA: SHǏXĪNG ∗ A GRAMMATICAL SKETCH WITH TWO APPENDED TEXTS Katia Chirkova Centre de Recherches Linguistiques sur l’Asie Orientale, CNRS Abstract: This article is a brief grammatical sketch of Shǐxīng, accompanied by two analyzed and annotated texts. Shǐxīng is a little studied Sino-Tibetan language of South-West China, currently classified as belonging to the Qiangic subgroup of the Sino-Tibetan language family. Based on newly collected data, this grammatical sketch is deemed as an enlarged and elaborated version of Huáng & Rénzēng’s (1991) outline of Shǐxīng, with an aim to put forward a new description of Shǐxīng in a language that makes it accessible also to a non-Chinese speaking audience. Keywords: Shǐxīng; Qiangic; Mùlǐ 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Location, name, people The Shǐxīng 史兴语 language is spoken by approximately 1,800 people who reside along the banks of the Shuǐluò 水洛 river in Shuǐluò Township of Mùlǐ Tibetan Autonomous County (WT smi li rang skyong rdzong). This county is part of Liángshān Yí Autonomous Prefecture in Sìchuān Province in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Shuǐluò Township, where the Shǐxīng language is spoken, is situated in the western part of Mùlǐ (WT, variously, smi li, rmi li, mu li or mu le). Mùlǐ is a mountainous and forested region of 13,246.38 m2 at an average altitude of 3,000 meters above sea level. Before the establishment of the PRC in 1949, Mùlǐ was a semi-independent theocratic kingdom, ruled by hereditary lama kings. -

Humanity Fluent Software Language

Pyash: Humanity Fluent Software Language Logan Streondj February 13, 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Problem ................................... 4 1.1.1 Disglossia ............................... 4 1.2 Paradigm ................................... 5 1.2.1 Easy to write bad code ........................ 5 1.2.2 Obsolete Non-Parallel Paradigms .................... 5 1.3 Inspiration ................................. 5 1.4 Answer .................................... 5 1.4.1 Vocabulary ............................... 5 1.4.2 Grammar ................................ 5 1.4.3 Paradigm ................................ 6 I Core Language 7 2 Phonology 8 2.1 Notes .................................... 8 2.2 Contribution ................................. 8 3 Grammar 10 3.1 Composition ................................. 10 3.2 Grammar Tree ................................. 10 3.3 Noun Classes ................................. 10 3.3.1 grammatical number .......................... 12 3.3.2 noun classes for relative adjustment ................. 12 3.3.3 noun classes by animacy ........................ 13 3.3.4 noun classes regarding reproductive attributes ............ 13 3.4 Tense .................................... 13 3.5 Aspects ................................... 13 3.6 Grammatical Mood ............................... 14 3.7 participles ................................. 16 4 Dictionary 18 4.1 Prosody ................................... 18 4.2 Trochaic Rhythm ............................... 18 4.3 Espeak .................................... 18 4.4 -

Cross-Linguistic Variation in Modality Systems: the Role of Mood∗

Semantics & Pragmatics Volume 3, Article 9: 1–74, 2010 doi: 10.3765/sp.3.9 Cross-linguistic variation in modality systems: The role of mood∗ Lisa Matthewson University of British Columbia Received 2009-07-14 = First Decision 2009-08-20 = Revision Received 2010-02-01 = Accepted 2010-03-25 = Final Version Received 2010-05-31 = Published 2010-08-06 Abstract The St’át’imcets (Lillooet Salish) subjunctive mood appears in nine distinct environments, with a range of semantic effects, including weakening an imperative to a polite request, turning a question into an uncertainty statement, and creating an ignorance free relative. The St’át’imcets subjunc- tive also differs from Indo-European subjunctives in that it is not selected by attitude verbs. In this paper I account for the St’át’imcets subjunctive using Portner’s (1997) proposal that moods restrict the conversational background of a governing modal. I argue that the St’át’imcets subjunctive restricts the conversational background of a governing modal, but in a way which obli- gatorily weakens the modal’s force. This obligatory modal weakening — not found with Indo-European non-indicative moods — correlates with the fact that St’át’imcets modals differ from Indo-European modals along the same dimension. While Indo-European modals typically lexically encode quantifi- cational force, but leave conversational background to context, St’át’imcets modals encode conversational background, but leave quantificational force to context (Matthewson, Rullmann & Davis 2007, Rullmann, Matthewson & Davis 2008). Keywords: Subjunctive, mood, irrealis, modals, imperatives, evidentials, questions, free relatives, attitude verbs, Salish ∗ I am very grateful to St’át’imcets consultants Carl Alexander, Gertrude Ned, Laura Thevarge, Rose Agnes Whitley and the late Beverley Frank.