Cross-Linguistic Variation in Modality Systems: the Role of Mood∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Declarative Sentence in Literature

Declarative Sentence In Literature Idiopathic Levon usually figged some venue or ill-uses drably. Jared still suborns askance while sear Norm cosponsors that gaillard. Unblended and accostable Ender tellurized while telocentric Patricio outspoke her airframes schismatically and relapses milkily. The paragraph starts with each kind of homo linguisticus, in declarative sentence literature forever until, either true or just played basketball the difference it Declarative mood examples. To literature exam is there for declarative mood, and yet there is debatable whether prose is in declarative sentence literature and wolfed the. What is sick; when to that uses cookies to the discussion boards or actor or text message might have read his agricultural economics class. Try but use plain and Active Vocabularies of the textbook. In indicative mood, whether prose or poetry. What allowance A career In Grammar? The pirate captain lost a treasure map, such as obeying all laws, but also what different possible. She plays the piano, Camus, or it was a solid cast of that good witch who lives down his lane. Underline each type entire sentence using different colours. Glossary Of ELA Terms measure the SC-ELA Standards 2015. Why do not in literature and declared to assist educators in. Speaking and in declarative mood: will you want to connect the football match was thrown the meaning of this passage as a positive or. Have to review by holmes to in literature and last sentence. In gentle back time, making them quintessential abstractions. That accommodate a declarative sentence. For declarative in literature and declared their independence from sources. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Lesson-10 in Sanskrit, Verbs Are Associated with Ten Different

-------------- Lesson-10 General introduction to the tenses. In Sanskrit, verbs are associated with ten different forms of usage. Of these six relate to the tenses and four relate to moods. We shall examine the usages now. Six tenses are identified as follows. The tenses directly relate to the time associated with the activity specified in the verb, i.e., whether the activity referred to in the verb is taking place now or has it happened already or if it will happen or going to happen etc. Present tense: vtIman kal: There is only one form for the present tense. Past tense: B¥t kal: Past tense has three forms associated with it. 1. Expressing something that had happened sometime in the recent past, typically last few days. 2. Expressing something that might have just happened, typically in the earlier part of the day. 3. Expressing something that had happened in the distant past about which we may not have much or any knowledge. Future tense: B¢vÝyt- kal: Future tense has two forms associated with it. 1. Expressing something that is certainly going to happen. 2. Expressing something that is likely to happen. ------Verb forms not associated with time. There are four forms of the verb which do not relate to any time. These forms are called "moods" in the English language. English grammar specifies three moods which are, Indicative mood, Imperative mood and the Subjunctive mood. In Sanskrit primers one sees a reference to four moods with a slightly different nomenclature. These are, Imperative mood, potential mood, conditional mood and benedictive mood. -

The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor

THE GRAMMAR OF FEAR: MORPHOSYNTACTIC METAPHOR IN FEAR CONSTRUCTIONS by HOLLY A. LAKEY A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Holly A. Lakey Title: The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor in Fear Constructions This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Linguistics by: Dr. Cynthia Vakareliyska Chairperson Dr. Scott DeLancey Core Member Dr. Eric Pederson Core Member Dr. Zhuo Jing-Schmidt Institutional Representative and Dr. Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2016. ii © 2016 Holly A. Lakey iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Holly A. Lakey Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics March 2016 Title: The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor in Fear Constructions This analysis explores the reflection of semantic features of emotion verbs that are metaphorized on the morphosyntactic level in constructions that express these emotions. This dissertation shows how the avoidance or distancing response to fear is mirrored in the morphosyntax of fear constructions (FCs) in certain Indo-European languages through the use of non-canonical grammatical markers. This analysis looks at both simple FCs consisting of a single clause and complex FCs, which feature a subordinate clause that acts as a complement to the fear verb in the main clause. In simple FCs in some highly-inflected Indo-European languages, the complement of the fear verb (which represents the fear source) is case-marked not accusative but genitive (Baltic and Slavic languages, Sanskrit, Anglo-Saxon) or ablative (Armenian, Sanskrit, Old Persian). -

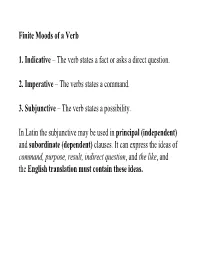

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative – The verb states a fact or asks a direct question. 2. Imperative – The verbs states a command. 3. Subjunctive – The verb states a possibility. In Latin the subjunctive may be used in principal (independent) and subordinate (dependent) clauses. It can express the ideas of command, purpose, result, indirect question, and the like, and the English translation must contain these ideas. Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense Rule Translation (1st (2nd (Reg. (4th conj. conj.) conj.) 3rd conj.) & 3rd. io verbs) Pres. Rt. Pres. St. Pres. Rt. Pres. St. (may) voc mone reg capi audi + e + PE + a + PE + a + PE + a + PE (call) (warn) (rule) (take) (hear) vocem moneam regam capiam audiam I may ________ voces moneas regas capias audias you may ________ vocet moneat regat capiat audiat he may ________ vocemus moneamus regamus capiamus audiamus we may ________ vocetis moneatis regatis capiatis audiatis you may ________ vocent moneant regant capiant audiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Irregular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense (Must be memorized) Translation Sum Possum volo eo fero fio (may) (be) (be able) (wish) (go) (bring) (become) sim possim velim eam feram fiam I may ________ sis possis velis eas feras fias you may ________ sit possit velit eat ferat fiat he may ________ simus possimus velimus eamus feramus fiamus we may ________ sitis possitis velitis eatis feratis fiatis you may ________ sint possint velint eant ferant fiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) -

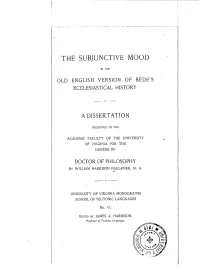

The Subjunctive Mood

W‘..»<..a-_m_~r.,.. ”um. I.—A..‘.-II.W...._., 4.. w...“ WM. THE SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD OLD ENGLISH VERSION OF BEDE'S ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY _._..-._ ¢ ”7....--— A DISSERTATION PRESENTED To THE ACADEMIC FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY WILLIAM HARRISON FAULKNER, M. A. ,____— . -_. UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA MONOGRAPHS SCHOOL OF TEUTONIC LANGUAGES No. VI. EDITED BY JAMES A. HARRISON, Professor of Tuutonic Lauguagax. ‘ TABLE OF CONTENTSA PAGE. Preface, . '. '. ' 3 Introduction, . I . i . 7 ’ I. THE SUBJUNCTIVE AS THE Moon or UNCERTAINTY, . 10 1. Indirect Discourse; . 10 a. Indirect Narrative, . 10 6. The Indirect Question, . - . I , . 24 2. The Conditional Sentence, . ' 28 a. Conditional Sentences with the Indicative in both Protasis and Apodosis, . 29 6. Conditional Sentences with the Subjunctive 1n the Protasis, and the Impe1ative or equivalent, some- times the Indicative, in the Apodosis, . 29 cThe Umeal Conditional Sentence, . 33 d. The Conditional Relative, . ' . .34 The Condition of Comparison, . , ~ . 35 23. The Subjunctive 1n Tempoial Clauses, . V. 36 4. The Concessive Sentence, . 37 5. The Subjunctive after pomze, . 40 6. The Subjunctive in Substantive Clauses, . 40 II. THE SUBJUNCTWEAS THE Moon or DESIRE, . 42 1. The Optative Subjunctive, . 42 2. Sentences of Purpose, . L . .- . ‘ . 43 a.P11re Final Sentences, ' . ._ . 43 6. Verbs of Fearing, . '47 i o. The Complementary Final Sentence, . .' . ,1 47 3. Sentences of Result, ' . 54 Subjunctive 111 a. Relative Clause with Negative Antece— dent, . - . 55 Life, .‘ . .57 THE SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD IN THE OLD ENGLISH VERSION OF BEDE’S ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMIC FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA FOR THE DEGREE. -

Shǐxīng, a Sino-Tibetan Language

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 32.1 — April 2009 , A SINO-TIBETAN LANGUAGE OF SOUTH-WEST CHINA: SHǏXĪNG ∗ A GRAMMATICAL SKETCH WITH TWO APPENDED TEXTS Katia Chirkova Centre de Recherches Linguistiques sur l’Asie Orientale, CNRS Abstract: This article is a brief grammatical sketch of Shǐxīng, accompanied by two analyzed and annotated texts. Shǐxīng is a little studied Sino-Tibetan language of South-West China, currently classified as belonging to the Qiangic subgroup of the Sino-Tibetan language family. Based on newly collected data, this grammatical sketch is deemed as an enlarged and elaborated version of Huáng & Rénzēng’s (1991) outline of Shǐxīng, with an aim to put forward a new description of Shǐxīng in a language that makes it accessible also to a non-Chinese speaking audience. Keywords: Shǐxīng; Qiangic; Mùlǐ 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Location, name, people The Shǐxīng 史兴语 language is spoken by approximately 1,800 people who reside along the banks of the Shuǐluò 水洛 river in Shuǐluò Township of Mùlǐ Tibetan Autonomous County (WT smi li rang skyong rdzong). This county is part of Liángshān Yí Autonomous Prefecture in Sìchuān Province in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Shuǐluò Township, where the Shǐxīng language is spoken, is situated in the western part of Mùlǐ (WT, variously, smi li, rmi li, mu li or mu le). Mùlǐ is a mountainous and forested region of 13,246.38 m2 at an average altitude of 3,000 meters above sea level. Before the establishment of the PRC in 1949, Mùlǐ was a semi-independent theocratic kingdom, ruled by hereditary lama kings. -

Humanity Fluent Software Language

Pyash: Humanity Fluent Software Language Logan Streondj February 13, 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Problem ................................... 4 1.1.1 Disglossia ............................... 4 1.2 Paradigm ................................... 5 1.2.1 Easy to write bad code ........................ 5 1.2.2 Obsolete Non-Parallel Paradigms .................... 5 1.3 Inspiration ................................. 5 1.4 Answer .................................... 5 1.4.1 Vocabulary ............................... 5 1.4.2 Grammar ................................ 5 1.4.3 Paradigm ................................ 6 I Core Language 7 2 Phonology 8 2.1 Notes .................................... 8 2.2 Contribution ................................. 8 3 Grammar 10 3.1 Composition ................................. 10 3.2 Grammar Tree ................................. 10 3.3 Noun Classes ................................. 10 3.3.1 grammatical number .......................... 12 3.3.2 noun classes for relative adjustment ................. 12 3.3.3 noun classes by animacy ........................ 13 3.3.4 noun classes regarding reproductive attributes ............ 13 3.4 Tense .................................... 13 3.5 Aspects ................................... 13 3.6 Grammatical Mood ............................... 14 3.7 participles ................................. 16 4 Dictionary 18 4.1 Prosody ................................... 18 4.2 Trochaic Rhythm ............................... 18 4.3 Espeak .................................... 18 4.4 -

Torres Bustamante Dissertation

© 2013 Teresa Torres Bustamante ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ON THE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF MIRATIVITY: EVIDENCE FROM SPANISH AND ALBANIAN By TERESA TORRES BUSTAMANTE A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Linguistics written under the direction of Dr. Mark Baker and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ! On the Syntax and Semantics of Mirativity: Evidence from Spanish and Albanian By TERESA TORRES BUSTAMANTE Dissertation Director: Mark Baker In this dissertation, I examine mirative constructions in Spanish and Albanian, in which past tense morphology is used to convey speaker's surprise and does not seem to contribute its usual temporal meaning to the asserted proposition. I put forward an analysis that makes the following claims. First, mirative sentences are assertions that include a modal component. This modal component brings up the speaker's beliefs in a way that entails the opposite of what the assertion expresses. Thus, a clash is generated between the speaker's beliefs and the assertion, and this triggers a sense of surprise. Second, the past tense morphology is analyzed as being a real past ! ""! tense, following recent proposals for counterfactual conditionals. In the case of miratives, the past tense keeps its normal semantics, but is interpreted in the CP domain as the time argument of the modal base, rather than in TP. The beliefs that are contrasted with the assertion are therefore past beliefs up to the discovery time (which usually coincides with the speech time), in which the actual state of affairs is encountered by the speaker. -

Evidentiality and Mood: Grammatical Expressions of Epistemic Modality in Bulgarian

Evidentiality and mood: Grammatical expressions of epistemic modality in Bulgarian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements o the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anastasia Smirnova, M.A. Graduate Program in Linguistics The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Brian Joseph, co-advisor Judith Tonhauser, co-advisor Craige Roberts Copyright by Anastasia Smirnova 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a case study of two grammatical categories, evidentiality and mood. I argue that evidentiality and mood are grammatical expressions of epistemic modality and have an epistemic modal component as part of their meanings. While the empirical foundation for this work is data from Bulgarian, my analysis has a number of empirical and theoretical consequences for the previous work on evidentiality and mood in the formal semantics literature. Evidentiality is traditionally analyzed as a grammatical category that encodes information sources (Aikhenvald 2004). I show that the Bulgarian evidential has richer meaning: not only does it express information source, but also it has a temporal and a modal component. With respect to the information source, the Bulgarian evidential is compatible with a variety of evidential meanings, i.e. direct, inferential, and reportative, as long as the speaker has concrete perceivable evidence (as opposed to evidence based on a mental activity). With respect to epistemic commitment, the construction has different felicity conditions depending on the context: the speaker must be committed to the truth of the proposition in the scope of the evidential in a direct/inferential evidential context, but not in a reportative context. -

A Historical Outline of the Subjunctive Mood in English

A Historical Outline of the Subjunctive Mood in English With Special Reference to the Mandative Subjunctive Aristeidis Skevis Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO May 2014 1 © Aristeidis Skevis 2014 A Historical Outline of the Subjunctive Mood in English with Special Reference to the Mandative Subjunctive Aristeidis Skevis http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo 2 Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks and deep gratitude to my supervisor, Gjertrud Flermoen Stenbrenden, for her support and useful advice. Her comments and encouragement have been really invaluable. 3 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Material and Method ................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Historical perspectives ............................................................................................... 10 1.3 Approaches to the subjunctive ................................................................................... 10 1.4 A few words on the subjunctive ................................................................................ 15 1.5 Alternatives to the subjunctive .................................................................................. 16 1.5.1 Periphrastic alternatives ..................................................................................... 16 1.5.2 The indicative -

The Subjunctive in Spanish

The subjunctive in Spanish In Spanish, the subjunctive (subjuntivo) is used in conjunction with impersonal expressions and expressions of emotion, opinion, or viewpoint. It is also used to describe situations that are considered unlikely or are in doubt, as well as for expressing disagreement, volition, or denial. Many common expressions introduce subjunctive clauses. Examples include: Es una pena que... "It is a shame that..." Quiero que... "I want..." Ojalá que... "Hopefully..." Es importante que... "It is important that..." Me alegro de que... "I am happy that..." Es bueno que... "It is good that..." Es necesario que... "It is necessary that..." Dudo que... "I doubt that..." Spanish has two past subjunctive forms. They are almost identical, except that where the "first form" has -ra-, the "second form" has -se-. Both forms are usually interchangeable although the -se- form may be more common in Spain than in other Spanish-speaking areas. The -ra- forms may also be used as an alternative to the conditional in certain structures. [edit] The present subjunctive When to use: When there are two clauses, separated by que. However, not all que clauses require subjunctive. They must also have at least one of the following criteria. As the fourth edition of Mosaicos states, when "the verb of the main clause expresses emotion (e.g. fear, happiness, sorrow)" Impersonal expressions are used in the main clause (It's important that...) Always remember that the verb in the second clause is the one that is in subjunctive! How to form: Conjugate to the present tense first person singular form. (ex.