Aspect, Modality, and Tense in Badiaranke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definiteness Determined by Syntax: a Case Study in Tagalog 1 Introduction

Definiteness determined by syntax: A case study in Tagalog1 James N. Collins Abstract Using Tagalog as a case study, this paper provides an analysis of a cross-linguistically well attested phenomenon, namely, cases in which a bare NP’s syntactic position is linked to its interpretation as definite or indefinite. Previous approaches to this phenomenon, including analyses of Tagalog, appeal to specialized interpretational rules, such as Diesing’s Mapping Hypothesis. I argue that the patterns fall out of general compositional principles so long as type-shifting operators are available to the gram- matical system. I begin by weighing in a long-standing issue for the semantic analysis of Tagalog: the interpretational distinction between genitive and nominative transitive patients. I show that bare NP patients are interpreted as definites if marked with nominative case and as narrow scope indefinites if marked with genitive case. Bare NPs are understood as basically predicative; their quantificational force is determined by their syntactic position. If they are syntactically local to the selecting verb, they are existentially quantified by the verb itself. If they occupy a derived position, such as the subject position, they must type-shift in order to avoid a type-mismatch, generating a definite interpretation. Thus the paper develops a theory of how the position of an NP is linked to its interpretation, as well as providing a compositional treatment of NP-interpretation in a language which lacks definite articles but demonstrates other morphosyntactic strategies for signaling (in)definiteness. 1 Introduction Not every language signals definiteness via articles. Several languages (such as Russian, Kazakh, Korean etc.) lack articles altogether. -

On Root Modality and Thematic Relations in Tagalog and English*

Proceedings of SALT 26: 775–794, 2016 On root modality and thematic relations in Tagalog and English* Maayan Abenina-Adar Nikos Angelopoulos UCLA UCLA Abstract The literature on modality discusses how context and grammar interact to produce different flavors of necessity primarily in connection with functional modals e.g., English auxiliaries. In contrast, the grammatical properties of lexical modals (i.e., thematic verbs) are less understood. In this paper, we use the Tagalog necessity modal kailangan and English need as a case study in the syntax-semantics of lexical modals. Kailangan and need enter two structures, which we call ‘thematic’ and ‘impersonal’. We show that when they establish a thematic dependency with a subject, they express necessity in light of this subject’s priorities, and in the absence of an overt thematic subject, they express necessity in light of priorities endorsed by the speaker. To account for this, we propose a single lexical entry for kailangan / need that uniformly selects for a ‘needer’ argument. In thematic constructions, the needer is the overt subject, and in impersonal constructions, it is an implicit speaker-bound pronoun. Keywords: modality, thematic relations, Tagalog, syntax-semantics interface 1 Introduction In this paper, we observe that English need and its Tagalog counterpart, kailangan, express two different types of necessity depending on the syntactic structure they enter. We show that thematic constructions like (1) express necessities in light of priorities of the thematic subject, i.e., John, whereas impersonal constructions like (2) express necessities in light of priorities of the speaker. (1) John needs there to be food left over. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

2008. Pruning Some Branches from 'Branching Spacetimes'

CHAPTER 10 Pruning Some Branches from “Branching Spacetimes” John Earman* Abstract Discussions of branching time and branching spacetime have become com- mon in the philosophical literature. If properly understood, these concep- tions can be harmless. But they are sometimes used in the service of debat- able and even downright pernicious doctrines. The purpose of this chapter is to identify the pernicious branching and prune it back. 1. INTRODUCTION Talk of “branching time” and “branching spacetime” is wide spread in the philo- sophical literature. Such expressions, if properly understood, can be innocuous. But they are sometimes used in the service of debatable and even downright per- nicious doctrines. The purpose of this paper is to identify the pernicious branching and prune it back. Section 2 distinguishes three types of spacetime branching: individual branch- ing, ensemble branching, and Belnap branching. Individual branching, as the name indicates, involves a branching structure in individual spacetime models. It is argued that such branching is neither necessary nor sufficient for indeterminism, which is explicated in terms of the branching in the ensemble of spacetime mod- els satisfying the laws of physics. Belnap branching refers to the sort of branching used by the Belnap school of branching spacetimes. An attempt is made to sit- uate this sort of branching with respect to ensemble branching and individual branching. Section 3 is a sustained critique of various ways of trying to imple- ment individual branching for relativistic spacetimes. Conclusions are given in Section 4. * Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, USA The Ontology of Spacetime II © Elsevier BV ISSN 1871-1774, DOI: 10.1016/S1871-1774(08)00010-7 All rights reserved 187 188 Pruning Some Branches from “Branching Spacetimes” 2. -

Layers and Operators in Lakota1 Avelino Corral Esteban Universidad Autónoma De Madrid

Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 36 (2015), 1-33 Layers and operators in Lakota1 Avelino Corral Esteban Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Abstract Categories covering the expression of grammatical information such as aspect, negation, tense, mood, modality, etc., are crucial to the study of language universals. In this study, I will present an analysis of the syntax and semantics of these grammatical categories in Lakota within the Role and Reference Grammar framework (hereafter RRG) (Van Valin 1993, 2005; Van Valin and LaPolla 1997), a functional approach in which elements with a purely grammatical function are treated as ´operators`. Many languages mark Aspect-Tense- Mood/Modality information (henceforth ATM) either morphologically or syntactically. Unlike most Native American languages, which exhibit an extremely complex verbal morphological system indicating this grammatical information, Lakota, a Siouan language with a mildly synthetic / partially agglutinative morphology, expresses information relating to ATM through enclitics, auxiliary verbs and adverbs, rather than by coding it through verbal affixes. 1. Introduction The organisation of this paper is as follows: after a brief account of the most relevant morpho- syntactic features exhibited by Lakota, Section 2 attempts to shed light on the distinction between lexical words, enclitics and affixes through evidence obtained in the study of this language. Section 3 introduces the notion of ´operator` and explores the ATM system in Lakota using RRG´s theory of operator system. After a description of each grammatical category, an analysis of the linear order exhibited by the Lakota operators with respect to the nucleus of the clause are analysed in Section 4, showing that this ordering reflects the scope relations between the grammatical categories conveyed by these operators. -

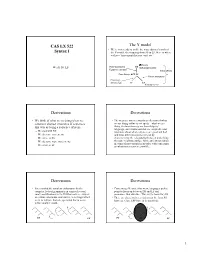

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Epistemic Modality, Mind, and Mathematics

Epistemic Modality, Mind, and Mathematics Hasen Khudairi June 20, 2017 c Hasen Khudairi 2017, 2020 All rights reserved. 1 Abstract This book concerns the foundations of epistemic modality. I examine the nature of epistemic modality, when the modal operator is interpreted as con- cerning both apriority and conceivability, as well as states of knowledge and belief. The book demonstrates how epistemic modality relates to the compu- tational theory of mind; metaphysical modality; deontic modality; the types of mathematical modality; to the epistemic status of undecidable proposi- tions and abstraction principles in the philosophy of mathematics; to the apriori-aposteriori distinction; to the modal profile of rational propositional intuition; and to the types of intention, when the latter is interpreted as a modal mental state. Each essay is informed by either epistemic logic, modal and cylindric algebra or coalgebra, intensional semantics or hyperin- tensional semantics. The book’s original contributions include theories of: (i) epistemic modal algebras and coalgebras; (ii) cognitivism about epistemic modality; (iii) two-dimensional truthmaker semantics, and interpretations thereof; (iv) the ground-theoretic ontology of consciousness; (v) fixed-points in vagueness; (vi) the modal foundations of mathematical platonism; (vii) a solution to the Julius Caesar problem based on metaphysical definitions availing of notions of ground and essence; (viii) the application of epistemic two-dimensional semantics to the epistemology of mathematics; and (ix) a modal logic for rational intuition. I develop, further, a novel approach to conditions of self-knowledge in the setting of the modal µ-calculus, as well as novel epistemicist solutions to Curry’s and the liar paradoxes. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Participant-Internal Possibility Modality and It's

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 5 S2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy September 2015 Participant-internal Possibility Modality and It’s Coding by – A Bil Analytical Construction in Kazakh Gulzada Salmyrzakyzy Yeshniyaz Botagoz Ermekovna Tassyrova Dauren Bakhytzhanovich Boranbayev Kazakh Ablai Khan University of international relations and world languages, The Republic of Kazakhstan 050022, Almaty, Muratbaev Street, 200 Ruslan Askarbekovich Yermagambetov The Korkyt Ata Kyzylorda State University, The Republic of Kazakhstan, 120014, Kyzylorda, Aiteke Bie Street, 29A Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n5s2p211 Abstract This paper discusses the semantic paradigm of the participant-internal possibility modality as a subcategory of modality and it’s coding in Kazakh with –A bil analytical construction. We will show that –A bil expresses all semantic properties of participant- internal possibility modality such as inherent/ learnt and mental/physical. Therefore constitutes the core of the functional- semantic field of the given modality. The paper also accounts for the relation of –A bil in modal usage with other category operators such as aspect, tense and voice. Keywords: modality, ability, participant-internal, converb, functional approach 1. Introduction Despite the available vast literature on modality there is still does not exist the single definition of the domain of modality in linguistics. Mostly modality is understood as a united meaning of its subcategories which are still under scrutiny and new concepts are being offered which make difficult to stabilize the semantics of modality. It is not once noted that “the number of modalities one decide upon is to some extent a matter of different ways of slicing the same cake” (Perkins, 1983, p.10). -

Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 40 Article 3 Issue 1 Fall 2008 2008 Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C. Farrell Quinnipiac University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Farrell, Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions, 40 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 1 (2008). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol40/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why Grammar Matters: Conjugating Verbs in Modern Legal Opinions Robert C. Farrell* I. INTRODUCTION Does it matter that the editors of thirty-three law journals, including those at Yale and Michigan, think that there is a "passive tense"? l Does it matter that the United States Courts of Appeals for the Sixth2 and Eleventh3 Circuits think that there is a "passive mood"? Does it matter that the editors of fourteen law reviews think that there is a "subjunctive tense"?4 Does it matter that the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit thinks that there is a "subjunctive voice'"? 5 There is, in fact, no "passive tense" or "passive mood." The passive is a voice. 6 There is no "subjunctive voice" or "subjunctive tense." The subjunctive is a mood.7 The examples in the first paragraph suggest that there is widespread unfamiliarity among lawyers and law students * B.A., Trinity College; J.D., Harvard University; Professor, Quinnipiac University School of Law. -

Representing-Time-An-Essay-On-Temporality-As

Representing Time To commemorate the centenary of J. E. McTaggart’s ‘The unreality of time’ (1908) Representing Time: An Essay on Temporality as Modality K. M. JASZCZOLT 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # K. M. Jaszczolt 2009 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book