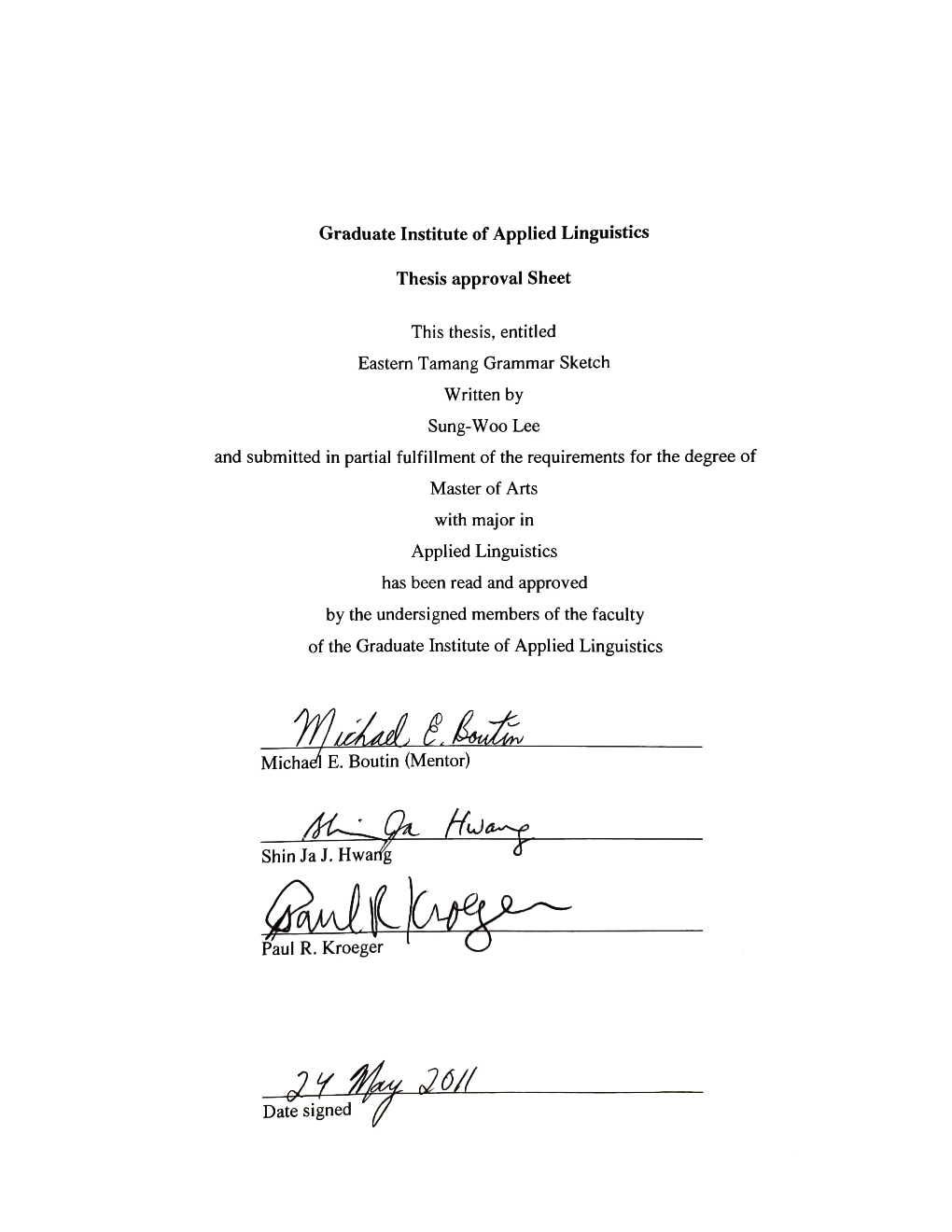

Eastern Tamang Grammar Sketch Written by Sung-Woo Lee and Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language in India

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 18:7 July 2018 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. C. Subburaman, Ph.D. (Economics) N. Nadaraja Pillai, Ph.D. Renuga Devi, Ph.D. Soibam Rebika Devi, M.Sc., Ph.D. Dr. S. Chelliah, M.A., Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Contents Language in India www.languageinindia.com is included in the UGC Approved List of Journals. Serial Number 49042. Materials published in Language in India www.languageinindia.com are indexed in EBSCOHost database, MLA International Bibliography and the Directory of Periodicals, ProQuest (Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts) and Gale Research. The journal is included in the Cabell’s Directory, a leading directory in the USA. Articles published in Language in India are peer-reviewed by one or more members of the Board of Editors or an outside scholar who is a specialist in the related field. Since the dissertations are already reviewed by the University-appointed examiners, dissertations accepted for publication in Language in India are not reviewed again. This is our 18th year of publication. All back issues of the journal are accessible through this link: http://languageinindia.com/backissues/2001.html Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:7 July 2018 Contents i C.P. Ajitha Sekhar, Ph.D. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

Becoming a Journalist in Exile

Becoming A Journalist In Exile Author/Editor T. P. Mishra Co-authors R. P. Subba (Bhutan) Subir Bhaumik (India) I. P. Adhikari (Bhutan) C. N. Timsina (Bhutan) Nanda Gautam (Bhutan) Laura Elizabeth Pohl (USA) Deepak Adhikari (Nepal) David Brewer (United Kingdom) Book: Becoming a journalist in exile Publisher: T. P. Mishra for TWMN - Bhutan Chapter Date of publication: March, 2009 Number of copies: 2000 (first edition) Layout: Lenin Banjade, [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-2-1279-3 Cover design: S.M. Ashraf Abir/www.mcc.com.bd, Bangladesh and Avinash Shrestha, Nepal. Cover: The photo displays the picture of the Chief Editor cum Publisher of The Bhutan Reporter (TBR) monthly, also author of "Becoming a journalist in exile" carrying 1000 issues of TBR (June 2007 edition) from the printing press to his apartment in Kathmandu. Photo: Laura Pohl. Copyright © TWMN – Bhutan Chapter 2009 Finance contributors: Vidhyapati Mishra, I.P. Adhikari, Nanda Gautam, Ganga Neopane Baral, Abi Chandra Chapagai, Harka Bhattarai, Toya Mishra, Parshu Ram Luitel, Durga Giri, Tej Man Rayaka, Rajen Giri, Y. P. Kharel, Bishwa Nath Chhetri, Shanti Ram Poudel, Kazi Gautam and Nandi K. Siwakoti Printed at: Dhaulagiri Offset Press, Kathmandu Price: The price will be sent at your email upon your interest to buy a copy. CONTENTS PART I 1. Basic concepts 1.1 Journalism and news 1.2 Writing for mass media 1.3 Some tips to good journalistic writing 2. Canons of journalism 2.1 The international code of journalist 2.2 Code of ethics 3. Becoming a journalist 4. Media and its role PART II 5. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Name : Krishna Prasad Chalise Date of Birth : 2027-05-21 V.S. (1970-09-06 AD) Sex : Male Nationality : Nepali Religion : Hindu Language Learned : Nepali, English, Baram, Hindi Father's Name : Bhesha Raj Chalise Address Permanent : Ward Number: 9, Musikot Municipality, Gulmi, Nepal Temporary : Ward Number: 9, Tarakeshwor Municipality, Kathmandu, Nepal Phone : 9841411441, 014026665 Email : [email protected] Academic Qualifications S.N. Level Institution Board Year 1 3 credit hour Ph. D. course in University of California, Santa 2008 Linguistics Barbara, US 2 MA (Linguistics) Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, TU 1998 Kathmandu 3 B.Ed (English &Maths) Faculty of Education, TU, Kirtipur, TU 1994 Kathmandu 4 I.Sc (Physics &Maths) Birendra M. Campus,Bharatpur, TU 1990 Chitwan 5 SLC Janajagriti High School, Kandebas, SLC 1988 Baglung Board Researches 1. 2017. Sociolinguistic Survey of the Belhare Language. A field research report(Co-author with AmbikaRegmi)submitted to the Linguistic Survey of Nepal (LinSuN), Central Department of Linguistics, Tribhuvan University. 2. 2017. Sociolinguistic Survey of the Sunuwar Language. A field research submitted to the Linguistic Survey of Nepal (LinSuN), Central Department of Linguistics, Tribhuvan University. 3. 20016. Acoustic Analysis of the Nepali Plosives.A research report submitted to the University Grants Commission, Bhaktapur, Nepal. 4. 2016. Sociolinguistic Survey of the Ghale/Northern GorkhaTamu Language. A field research report(Co-author with PratigyaRegmi)submitted to the Linguistic Survey of Nepal (LinSuN), Central Department of Linguistics, Tribhuvan University. 5. 2015. An Investigation of Genetic Affinity of the Languages: Baram, Thami, Chepang, Newar and Magar. A research report submitted to Research Division, the Office of the Rector, Tribhuvan University. -

Non-Pronominalised Himalayan Languages

NON-PRONOMINALISED HIMALAYAN LANGUAGES LEPCHA-TAMANG-GURUNG-NEWARI-MANGARI-SUNWAR 328 329 LEPCHA S.GANESH BASKARAN 1. INTRODUCTION The present study gives out the grammatical sketch of Lepcha language spoken in Sikkim state based on the data collected during the field investigation from June 1997 to September 1997. 1.1 FAMILY AFFILIATION According to Grierson (1909: Vol. III) Lepcha Language belongs to the Non- Pronominalized Himalayan group of TibetoBurman sub family. As per the subsequent classification by Paul Benedict Lepcha (in Sikkim) belongs to the “Himalayan” group of “Tibetan –Kanauri (Bodish-Himalaya)” branch of Tibeto Burman sub-family. [Benedict: 1972] 1.2 LOCATION According to G. A. Grierson 1909 (reprint 1967,p-233) the Lepchas are considered as the oldest inhabitants of Sikkim. They are also found in Western Bhutan, Eastern Nepal and in Darjeeling district of West Bengal. In Indian Census the Lepcha is returned mainly from Sikkim and West Bengal. 1.3 SPEAKERS STRENGTH Language-Mother Tongue- Bilingualism The speakers’ strength of Lepcha in respect of language / mother tongue and bilingualism/ trilingualism as per 2001 Census publication is given below. Language LEPCHA TOTAL M F RURAL M F URBAN M F INDIA 50,629 26,111 24,518 48,295 24,954 23,341 2,334 1,157 1,177 Sikkim 35,728 18,505 17,223 34,289 17,753 16,536 1,439 752 687 Mother tongue LEPCHA TOTAL M F RURAL M F URBAN M F INDIA 50,629 26,111 24,518 48,295 24,954 23,341 2,334 1,157 1,177 Sikkim 35,728 18,505 17,223 34,289 17,753 16,536 1,439 752 687 330 1.4. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Mandarin Chinese Evenki Oroqen Tuva China Buriat Russian Southern Altai Oroqen Mongolia Buriat Oroqen Russian Evenki Russian Evenki Mongolia Buriat Kalmyk-Oirat Oroqen Kazakh China Buriat Kazakh Evenki Daur Oroqen Tuva Nanai Khakas Evenki Tuva Tuva Nanai Languages of China Mongolia Buriat Tuva Manchu Tuva Daur Nanai Russian Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Russian Kalmyk-Oirat Halh Mongolian Manchu Salar Korean Ta tar Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Northern UzbekTuva Russian Ta tar Uyghur SalarNorthern Uzbek Ta tar Northern Uzbek Northern Uzbek RussianTa tar Korean Manchu Xibe Northern Uzbek Uyghur Xibe Uyghur Uyghur Peripheral Mongolian Manchu Dungan Dungan Dungan Dungan Peripheral Mongolian Dungan Kalmyk-Oirat Manchu Russian Manchu Manchu Kyrgyz Manchu Manchu Manchu Northern Uzbek Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Korean Kyrgyz Northern Uzbek West Yugur Peripheral Mongolian Ainu Sarikoli West Yugur Manchu Ainu Jinyu Chinese East Yugur Ainu Kyrgyz Ta jik i Sarikoli East Yugur Sarikoli Sarikoli Northern Uzbek Wakhi Wakhi Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Ainu Tu Wakhi Wakhi Khowar Tu Wakhi Uyghur Korean Khowar Domaaki Khowar Tu Bonan Bonan Salar Dongxiang Shina Chilisso Kohistani Shina Balti Ladakhi Japanese Northern Pashto Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Amdo Tibetan Northern Hindko Kashmiri Purik Choni Ladakhi Changthang Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Japanese Bhadrawahi Zangskari Kashmiri Baima Ladakhi Pangwali Mandarin Chinese Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Japanese Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Ladakhi Northern Qiang -

Conferences and Seminars

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 8 Number 3 Himalayan Research Bulletin Article 10 1988 Conferences and Seminars Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation . 1988. Conferences and Seminars. HIMALAYA 8(3). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol8/iss3/10 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION 86th ANNUAL MEETING Phoenix, Arizona, November 16-20, 1988 PARISH, Steven (UC-San Diego) MORAL KNOWING AND NEWAR NARRA TlYES: ANTIHIERARCHICAL MORALITY TALES FROM AN ARCHAIC HINDU CITY The Newars of Nepal use narratives to help create a Hindu "turn of mind," and many stories affirm the values of traditional caste hierarchy. But not all do so; some narratives challenge hierarchy. Newar narratives, like Newar rituals, help organize moral consciousness: Newars know themselves as moral beings through narratives and rituals. But narratives are more fluid than ritual; narratives permit a range of revaluations of social roles and self. In antihierarchical narratives, caste hierarchy can be reimagined or neutralized, and an alternative moral awareness established. SWEETSER, Anne T (Harvard) RE-CREATION OF LEGITIMACY: MORALITY AND POWER IN THE ORAL HISTORY OF KAGHAN VALLEY, NORTH-WEST FRONTIER PROVINCE, PAKISTAN The aim of oral history in the Kaghan Valley is reassertion of the moral legitimacy of domination by the landlord family. -

The Tamang in Nepal

Südasien-Chronik - South Asia-Chronicle 1/2011, S. 393-437 © Südasien-Seminar der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin ISBN:978-3-86004-263-2 Negotiating Ethnic Identity in the Himalaya - The Tamang in Nepal ANNE KUKUCZKA [email protected] “[T]he discourse on ethnicity has escaped from academia and into the field. [...] [T]here is certainly a designer organism out there now, bred in the laboratory and released into the world to be fed by politicians, journalists, and ordinary citizens through their words and actions” (Banks 1996: 189). In the Nepalese Constituent Assembly elections of 2008 among the 74 registered parties, the Tamsaling Nepal Rastriya Dal (Tamsaling Nepal National Party, TRD) promoted the concept of transforming Nepal into a federal state based on ethnic groups’1 ancestral homelands. The claim for ethnic groups’ self-determination is one of the major political is- sues the Constituent Assembly is facing today while working towards a new constitution for what was the world’s last Hindu kingdom. Already in the early 1990s, Parshuram Tamang, who at that time was head of the Nepal Tamang Ghedung (Nepal Tamang Association, NTG), Nepal’s largest national Tamang organization, argued for a cantonal approach and the reorganization of the local government in order to decentralize 393 power and enable ethnic communities to actively engage in politics. Significantly, as early as 1992 he referred to the group that constitutes 5.6 percent of the total Nepalese population, and thereby forms the third largest ethnic group in Nepal2, as a “nation, which has inhabited [the] hills for longer than any other group” (Tamang 1992: 25). -

Strategies for Analyzing Tone Languages1

Vol. 8 (2014), pp. 462–489 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24614 Strategies for analyzing tone languages1 Alexander R. Coupe Nanyang Technological University This paper outlines a method of auditory and acoustic analysis for determining the tonemes of a language starting from scratch, drawing on the author’s experience of recording and analyzing tone languages of north-east India. The methodology is applied to a prelimi- nary analysis of tone in the Thang dialect of Khiamniungan, a virtually undocumented language of extreme eastern Nagaland and adjacent areas of the Sagaing Division Myan- mar (Burma). Following a discussion of strategies for ensuring that data appropriate for tonal analysis will be recorded, the practical demonstration begins with a description of how tone categories can be established according to their syllable type in the preliminary auditory analysis. The paper then uses this data to describe a method of acoustic analysis that ultimately permits the representation of pitch shapes as a function of absolute mean duration. The analysis of grammatical tones, floating tones and tone sandhi are exemplified with Mongsen Ao data, and a description of a perception test demonstrates how this can be used to corroborate the auditory and acoustic analysis of a tone system. 1. INTRODUCTION. This paper outlines a method of auditory and acoustic analysis for determining the tonemes of a language starting from scratch, drawing on my experience of recording and analyzing the tonal Tibeto-Burman languages spoken -

Automatic Extraction of Quasi-Synonyms from Bilingual Nepali

Nepalese Linguistics Volume 28 November 2013 Chief Editor Prof. Dr. Dan Raj Regmi Editors Dr. Balaram Prasain Mr. Krishna Prasad Chalise Office Bearers for 2012-2014 President Krishna Prasad Parajuli Vice-President Bhim Lal Gautam General Secretary Kamal Poudel Secretary (Office) Bhim Narayan Regmi Secretary (General) Kedar Bilash Nagila Treasurer Krishna Prasad Chalise Member Dev Narayan Yadav Member Netra Mani Dumi Rai Member Karnakhar Khatiwada Member Ambika Regmi Member Suren Sapkota Editorial Board Chief Editor Prof. Dr. Dan Raj Regmi Editors Dr. Balaram Prasain Mr. Krishna Prasad Chaise Nepalese Linguistics is a journal published by Linguistic Society of Nepal. It publishes articles related to the scientific study of languages, especially from Nepal. The views expressed therein are not necessary shared by the committee on publications. Published by: Linguistic Society of Nepal Kirtipur, Kathmandu Nepal Copies: 500 © Linguistic Society of Nepal ISSN -0259-1006 Price: NC 400/- (Nepali) IC 350/-(India) USD 10 Life membership fees include subscription for the journal. SPECIAL THANKS TO NEPAL ACADEMY AND UNESCO OFFICE IN KATHMANDU Nepal Academy (Nepal Pragya Pratisthan) was founded in June 22, 1957 by the then His Late Majesty King Mahendra as Nepal Sahitya Kala Academy. It was later renamed Nepal Rajkiya Pragya Pratisthan and now it is named as Nepal Pragya Prastisthan. This prestigious national academic institution is committed to enhancing the language, culture, philosophy and social sciences in Nepal. The major objectives of Nepal -

Ghale Language: a Brief Introduction

Nepalese Linguistics Volume 23 November, 2008 Chief Editor: Jai Raj Awasthi Editors: Ganga Ram Gautam Bhim Narayan Regmi Office Bearers for 2008-2010 President Govinda Raj Bhattarai Vice President Dan Raj Regmi General Secretary Balaram Prasain Secretary (Office) Krishna Prasad Parajuli Secretary (General) Bhim Narayan Regmi Treasurer Bhim Lal Gautam Member Bal Mukunda Bhandari Member Govinda Bahadur Tumbahang Member Gopal Thakur Lohar Member Sulochana Sapkota (Bhusal) Member Ichchha Purna Rai Nepalese Linguistics is a Journal published by Linguistic Society of Nepal. This Journal publishes articles related to the scientific study of languages, especially from Nepal. The views expressed therein are not necessarily shared by the committee on publications. Published by: Linguistic Society of Nepal Kirtipur, Kathmandu Nepal Copies: 500 © Linguistic Society of Nepal ISSN – 0259-1006 Price: NC 300/- (Nepal) IC 300/- (India) US$ 6/- (Others) Life membership fees include subscription for the journal. TABLE OF CONTENTS Tense and aspect in Meche Bhabendra Bhandari 1 Complex aspects in Meche Toya Nath Bhatta 15 An experience of translating Nepali grammar into English Govinda Raj Bhattarai 25 Bal Ram Adhikari Compound case marking in Dangaura Tharu Edward D. Boehm 40 Passive like construction in Darai Dubi Nanda Dhakal 58 Comparative study of Hindi and Punjabi language scripts Vishal Goyal 67 Gurpreet Singh Lehal Some observations on the relationship between Kaike and Tamangic Isao Honda 83 Phonological variation in Srinagar variety of Kashmiri -

European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 41 2012 Ebhr 41

EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH 41 2012 RESEARCH OF HIMALAYAN BULLETIN EUROPEAN EBHR 41 ARTICLES The Kinship Terminology of the Sangtam Nagas 9 Pascal Bouchery and Lemlila Sangtam 41 Vote For Prashant Tamang: Representations of an Indian Idol in 30 Autumn-Winter 2012 the Nepali print media and the retreat of multiculturalism Harsha Man Maharjan ‘Objectionable Contents’: The policing of the Nepali print media 58 during the 1950s Lokranjan Parajuli Maoist gates in Jumla and Mugu districts: Illustrations of the 84 ‘People’s War’ Satya Shrestha-Schipper ‘This is How we Joke’. Towards an appreciation of alternative values 100 in performances of gender irony among the Gaddi of Himachal Anja Wagner CONFERENCE REPORT 121 EBHR BOOK REVIEWS 125 EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH Autumn-Winter 2012 published by the EBHR Editorial Committee in conjunction with Social Science Baha, Kathmandu, Nepal European Bulletin of Himalayan Research The European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR) was founded by the late Richard Burghart in 1991. It is the result of a partnership between France (CNRS), Germany (South Asia Institute, University of Heidelberg) and the United Kingdom (School of Oriental and African Studies [SOAS]). From 2010 to 2014 the Editorial Board is based in the UK and comprises Michael Hutt (SOAS, Managing Editor), Ben Campbell (University of Durham), Ian Harper (University of Edinburgh), Sondra Hausner (University of Oxford), Heleen Plaisier, Sara Shneiderman (Yale University), and Arik Moran (University of Tel Aviv, book