Ghale Language: a Brief Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation

Women’s Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation Emerging issues, adaptive practices, and priorities in Nepal ICIMOD Working Paper 2014/3 1 About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalization and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. ICIMOD gratefully acknowledges the support of its core donors: The Governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. 2 ICIMOD Working Paper 2014/3 Women’s Empowerment at the Frontline of Adaptation: Emerging issues, adaptive practices, and priorities in Nepal Dibya Devi Gurung, WOCAN Suman Bisht, ICIMOD International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, Nepal, August 2014 Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright © 2014 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) All rights reserved. -

Pramod Thapa Somnath Aryal

Pramod Thapa Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Somnath Aryal Officer Account Department Account Email: [email protected] Kush Sunder Shrestha Sr. Admin Officer Email: [email protected] Basanta Blown Officer Email: [email protected] Administration Chintamani Rijal Asst. Coordinator Email: [email protected] Nil Prasad Subedi Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Parmila Rai Officer Email: [email protected] Administration Ravi Khadka Supervisor Pradeep Khadka Support Staff Narayan Budhathoki Support Staff Administration Narayan Mangrati Support Staff Naresh Kumar Sunuwar Support Staff Shani Kumar Khulal Support Staff Administration Basulal Deula Support Staff Surya Bahadur Thapa Support Staff Administration Abani Tandukar Sr. Officer Counseling Subash Chandra Pandey Discipline Incharge Khindra Kafle Discipline Supervisor Discipline Sangita Dhakal Discipline Staff Hari Prasad Niraula Head, ECA ECA Email: [email protected] Mukesh Chandra System Administrator Email: [email protected] IT Department Govinda Aryal Officer Email: [email protected] Examination Indu Shrestha Officer Email: [email protected] Mousami Shreepali Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Desk Santoshi Bist – Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Front Rabina Shakya Jr. Officer Umesh Karmacharya Support Staff Gardening Basundhara Chhetri Hostel Supervisor, Girls Bhagwati Khatri Support Staff Hostel Durga Basnet Support Staff Suraj Air Hostel Supervisor, Boys Hostel Chandra Bahadur Gurung Lab Assistant, Biology Navaraj Lamichhane Lab Assistant, Microbiology Laboratory Shisam Shrestha Lab Assistant, Chemistry Giriraj Pokhrel Officer Email: [email protected] Library Sunita Shrestha Officer Email: [email protected] Shambhu Singh Maharjan Storekeeper Store Email: [email protected] Bishnu Raya Head Bus Driver Balaram Thapa Bus Driver Transportation Raj Kumar Khadka Bus Driver Bishwash Chaudhari Support Staff Chhiring Tamang Support Staff Transportation Subash Tharu Support Staff Chandan Deula Parking Staff Bijay Thapa Support Staff Transportation. -

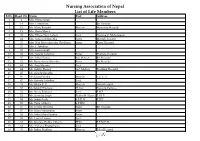

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

43524-014: Kathmandu Valley Wastewater Management Project

Initial Environmental Examination Document stage: Updated Number: 43524-014 March 2020 NEP: Kathmandu Valley Wastewater Management Project – Core Area Sewer Network of Lalitpur Metropolitan City (SN-03) Prepared by the Project Implementation Directorate, Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited, Ministry of Water Supply, Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Initial Environmental Examination, Vol. I March 2020 NEP: Kathmandu Valley Wastewater Management Project L-3000 Core Area Sewer Network of Lalitpur Metropolitan City Prepared by the Project Implementation Directorate, Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited, Ministry of Water Supply, Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank i Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) of SN-03 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of March 2020) Currency unit - Nepalese rupee (NRs/NRe) $1.00 = NRs 116.91 In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank CASSC Community Awareness and Social Safeguard Consultant -

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between the Hanns Seidel Foundation Pakistan and the Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad Islamabad, 2020 Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Edited by Sarah Holz Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office and Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan Acknowledgements Thank you to Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office for the generous and continued support for empirical research in Pakistan, in particular: Kristóf Duwaerts, Omer Ali, Sumaira Ihsan, Aisha Farzana and Ahsen Masood. This volume would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of a large number of people. Sara Gurchani, who worked as the research assistant of the collaboration in 2018 and 2019, provided invaluable administrative, organisational and editorial support for this endeavour. A big thank you the HSF grant holders of 2018 who were not only doing their own work but who were also actively engaged in the organisation of the international workshop and the lecture series: Ibrahim Ahmed, Fateh Ali, Babar Rahman and in particular Adil Pasha and Mohsinullah. Thank you to all the support staff who were working behind the scenes to ensure a smooth functioning of all events. A special thanks goes to Shafaq Shafique and Muhammad Latif sahib who handled most of the coordination. Thank you, Usman Shah for the copy editing. The research collaboration would not be possible without the work of the QAU faculty members in the year 2018, Dr. Saadia Abid, Dr. -

Syntactic Aspects of Nominalization in Five Tibeto-Burman Languages of the Himalayan Area1

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 31.2 — October 2008 SYNTACTIC ASPECTS OF NOMINALIZATION IN FIVE TIBETO-BURMAN LANGUAGES OF THE HIMALAYAN AREA1 Carol Genetti University of California, Santa Barbara Research Centre for Linguistic Typology A.R. Coupe Ellen Bartee Kristine Hildebrandt You-Jing Lin La Trobe University SIL SIUE UC Santa Barbara The goal of this paper is to describe some of the syntactic structures that are created through nominalization processes in Himalayan Tibeto-Burman languages and the relationships between those structures. These include both structures involving the nominalization of clauses (e.g. complement clauses, relative clauses) and structures involving the nominalization of verbs and predicates (e.g. the derivation of nouns and adjectives). We will argue that, synchronically, clausal nominalization, structurally represented as [clause]NP, is the basic structure underlying many of the nominalizing constructions in these languages, even though individual constructions embed and alter this structure in interesting ways. In addition to clausal nominalization, we will illustrate the presence of derivational nominalization, represented as [V-NOM]N and [V-NOM]ADJ, although some nominal derivations target the predicate, not the verb root as their domain. We will also demonstrate that derivational nominalization can be seen as having developed from clausal nominalization, at least for some forms in some languages, and that the opposite direction of development, from derivational to clausal structures, is also attested. We will conclude with some syntactic observations pertinent to recent claims made on the historical relationship between nominalization and relativization, demonstrating that there are various ways that these structures can be related. -

Persian Language

v course reference persian language r e f e r e n c e زبان فارسی The Persian Language 1 PERSIAN OR FARSI? In the U.S., the official language of Iran is language courses in “Farsi,” universities and sometimes called “Farsi,” but sometimes it is scholars prefer the historically correct term called “Persian.” Whereas U.S. government “Persian.” The term “Farsi” is better reserved organizations have traditionally developed for the dialect of Persian used in Iran. 2 course reference AN INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGE Persian is a member of the Indo-European Persian has three major dialects: Farsi, language family, which is the largest in the the official language of Iran, spoken by 50 world. percent of the population; Dari, spoken mostly in Afghanistan, and Tajiki, spoken Persian falls under the Indo-Iranian branch, in Tajikistan. Other languages in Iran are comprising languages spoken primarily Arabic, New Aramaic, Armenian, Georgian in Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, India, and Turkic dialects such as Azerbaidjani, Bangladesh, areas of Turkey and Iraq, and Khalaj, Turkemenian and Qashqa”i. some of the former Soviet Union. INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES GERMANIC INDO-IRANIAN HELLENIC CELTIC ITALIC BALTO-SLAVIC Polish Russin Indic Greek Serbo-Crotin North Germnic Ltin Irnin Mnx Irish Welsh Old Norse Swedish Scottish Avestn Old Persin Icelndic Norwegin French Spnish Portuguese Itlin Middle Persin West Germnic Snskrit Rumnin Ctln Frsi Kurdish Bengli Urdu Gujrti Hindi Old High Germn Old Dutch Anglo-Frisin Middle High Germn Middle Dutch Old Frisin Old English Germn Flemish Dutch Afrikns Frisin Middle English Yiddish Modern English vi v Persian Language 3 ALPHABET: FROM PAHLAVI TO ARABIC History tells us that Iranians used the Pahlavi Unlike English, Persian is written from right writing system prior to the 7th Century. -

3.1 Tibeto-Burman Languages 3.2 Indo-Aryan Languages and Others • Section 4

Writing of languages and Linguistic Survey of Nepal (LinSuN) Dr. Dan Raj Regmi Head Central Department of Linguistics Tribhuvan University, Nepal Director Linguistic Survey of Nepal [email protected] 1 Organization • Section 1. Linguistic survey of Nepal: Vision, reason, main objectives, survey and survey reports • Section 2. Writing: Linguistic and social reality • Section 3. Issues of writing of languages in Nepal 3.1 Tibeto-Burman languages 3.2 Indo-Aryan languages and others • Section 4. Adaptation of Devanagari scripts • Section 5. The policy of LinSuN to develop orthographies for unwritten languages • Section 6: Summary 2 1. Linguistic survey of Nepal The linguistic survey of Nepal has been conducted under Central Department of Nepal with the aegis of National Planning Commission, Government of Nepal since 2009. 1.1 Vision “… to lay a foundation that provides for the linguistic rights of the citizens of Nepal so that all her people, regardless of linguistic background, will be included in the overall fabric of the nation.” 1.2 Rationale “…not sufficient understanding in the diversity of its people and the languages they speak. Even a full identification of the number of languages and dialects has not yet been possible. If efforts in linguistic inclusion will have any success, they must begin first with an understanding of the full extent of the linguistic and ethnic diversity of the country.” 3 1.3 Reasons . To develop orthographies for unwritten or preliterate languages of Nepal . To determine the role of language in primary and adult education . To identify and document minority languages facing extinction, and . To implement the socially inclusive provisions made in the Interim Plan, National Planning Commission 2007 4 1.4 Main objectives . -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Himalayan Linguistics a Free Refereed Web Journal and Archive Devoted to the Study of the Languages of the Himalayas

himalayan linguistics A free refereed web journal and archive devoted to the study of the languages of the Himalayas Himalayan Linguistics Issues in Bahing orthography development Maureen Lee CNAS; SIL abstract Section 1 of this paper summarizes the community-based process of Bahing orthography development. Section 2 introduces the criteria used by the Bahing community members in deciding how Bahing sounds should be represented in the proposed Bahing orthography with Devanagari used as the script. This is followed by several sub-sections which present some of the issues involved in decision-making, the decisions made, and the rationale for these decisions for the proposed Bahing Devanagari orthography: Section 2.1 mentions the deletion of redundant Nepali Devanagari letters for the Bahing orthography; Section 2.2 discusses the introduction of new letters to represent Bahing sounds that do not exist in Nepali or are not distinctively represented in the Nepali Alphabet; Section 2.3 discusses the omission of certain dialectal Bahing sounds in the proposed Bahing orthography; and Section 2.4 discusses various length related issues. keywords Kiranti, Bahing language, Bahing orthography, orthography development, community-based orthography development This is a contribution from Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 10(1) [Special Issue in Memory of Michael Noonan and David Watters]: 227–252. ISSN 1544-7502 © 2011. All rights reserved. This Portable Document Format (PDF) file may not be altered in any way. Tables of contents, abstracts, and submission guidelines are available at www.linguistics.ucsb.edu/HimalayanLinguistics Himalayan Linguistics, Vol. 10(1). © Himalayan Linguistics 2011 ISSN 1544-7502 Issues in Bahing orthography development Maureen Lee CNAS; SIL 1 Introduction 1.1 The Bahing language and speakers Bahing (Bayung) is a Tibeto-Burman Western Kirati language, with the traditional homelands of their speakers spanning the hilly terrains of the southern tip of Solumkhumbu District and the eastern part of Okhaldhunga District in eastern Nepal. -

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Diagnostic of Selected Sectors in Nepal

GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2020 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 8632 4444; Fax +63 2 8636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2020. ISBN 978-92-9262-424-8 (print); 978-92-9262-425-5 (electronic); 978-92-9262-426-2 (ebook) Publication Stock No. TCS200291-2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS200291-2 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. -

Multilingual Education and Nepal Appendix 3

19. Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove and Mohanty, Ajit. Policy and Strategy for MLE in Nepal Report by Tove Skutnabb-Kangas and Ajit Mohanty Consultancy visit 4-14 March 2009i Sanothimi, Bhaktapur: Multilingual Education Program for All Non-Nepali Speaking Students of Primary Schools of Nepal. Ministry of Education, Department of Education, Inclusive Section. See also In Press, for an updated version. List of Contents List of Contents List of Appendices List of Tables List of Figures List of Abbreviations 1. Introduction: placing language in education issues in Nepal in a broader societal, economic and political framework 2. Broader Language Policy and Planning Perspectives and Issues 2.1. STEP 1 in Language Policy and Language Planning: Broad-based political debates about the goals of language 2.2. STEP 2 in Educational Language Policy and Language Planning: Realistic language proficiency goal/aim in relation to the baseline 2.3. STEP 3 in Educational Language Planning: ideal goals and prerequisites compared with characteristics of present schools 2.4. STEP 4 in Educational Language Planning: what has characterized programmes with high versus low success? 2.5. STEP 5 in Educational Language Planning: does it pay off to maintain ITM languages? 3. Scenarios 3.1. Introduction 3.2. Models with often harmful results: dominant-language-medium (subtractive assimilatory submersion) 3.3. Somewhat better but not good enough results: early-exit transitional models 3.4. Even better results: late-exit transitional models 3.5. Strongest form: self-evident mother tongue medium models with no transition 4. Experiences from Nepal: the situation today 5. Specific challenges in Nepal: implementation strategies 5.1.