First Draft of the Report Was Prepared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020)

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020) Editor-In-Chief Shree Ram Bajagain Editor Aarya Adhikari Editorial Team Govinda Prasad Tripathee Ramesh Prasad Timalsina Data Analyst Anuj KC Cover/Graphic Designer Gita Mali For Human Rights and Social Justice Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) Nagarjun Municipality-10, Syuchatar, Kathmandu POBox : 2726, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5218770 Fax:+977-1-5218251 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.insec.org.np; www.inseconline.org All materials published in this book may be used with due acknowledgement. First Edition 1000 Copies February 19, 2021 © Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) ISBN: 978-9937-9239-5-8 Printed at Dream Graphic Press Kathmandu Contents Acknowledgement Acronyms and Abbreviations Foreword CHAPTERS Chapter 1 Situation of Human Rights in 2020: Overall Assessment Accountability Towards Commitment 1 Review of the Social and Political Issues Raised in the Last 29 Years of Nepal Human Rights Year Book 25 Chapter 2 State and Human Rights Chapter 2.1 Judiciary 37 Chapter 2.2 Executive 47 Chapter 2.3 Legislature 57 Chapter 3 Study Report 3.1 Status of Implementation of the Labor Act at Tea Gardens of Province 1 69 3.2 Witchcraft, an Evil Practice: Continuation of Violence against Women 73 3.3 Natural Disasters in Sindhupalchok and Their Effects on Economic and Social Rights 78 3.4 Problems and Challenges of Sugarcane Farmers 82 3.5 Child Marriage and Violations of Child Rights in Karnali Province 88 36 Socio-economic -

Pramod Thapa Somnath Aryal

Pramod Thapa Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Somnath Aryal Officer Account Department Account Email: [email protected] Kush Sunder Shrestha Sr. Admin Officer Email: [email protected] Basanta Blown Officer Email: [email protected] Administration Chintamani Rijal Asst. Coordinator Email: [email protected] Nil Prasad Subedi Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Parmila Rai Officer Email: [email protected] Administration Ravi Khadka Supervisor Pradeep Khadka Support Staff Narayan Budhathoki Support Staff Administration Narayan Mangrati Support Staff Naresh Kumar Sunuwar Support Staff Shani Kumar Khulal Support Staff Administration Basulal Deula Support Staff Surya Bahadur Thapa Support Staff Administration Abani Tandukar Sr. Officer Counseling Subash Chandra Pandey Discipline Incharge Khindra Kafle Discipline Supervisor Discipline Sangita Dhakal Discipline Staff Hari Prasad Niraula Head, ECA ECA Email: [email protected] Mukesh Chandra System Administrator Email: [email protected] IT Department Govinda Aryal Officer Email: [email protected] Examination Indu Shrestha Officer Email: [email protected] Mousami Shreepali Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Desk Santoshi Bist – Jr. Officer Email: [email protected] Front Rabina Shakya Jr. Officer Umesh Karmacharya Support Staff Gardening Basundhara Chhetri Hostel Supervisor, Girls Bhagwati Khatri Support Staff Hostel Durga Basnet Support Staff Suraj Air Hostel Supervisor, Boys Hostel Chandra Bahadur Gurung Lab Assistant, Biology Navaraj Lamichhane Lab Assistant, Microbiology Laboratory Shisam Shrestha Lab Assistant, Chemistry Giriraj Pokhrel Officer Email: [email protected] Library Sunita Shrestha Officer Email: [email protected] Shambhu Singh Maharjan Storekeeper Store Email: [email protected] Bishnu Raya Head Bus Driver Balaram Thapa Bus Driver Transportation Raj Kumar Khadka Bus Driver Bishwash Chaudhari Support Staff Chhiring Tamang Support Staff Transportation Subash Tharu Support Staff Chandan Deula Parking Staff Bijay Thapa Support Staff Transportation. -

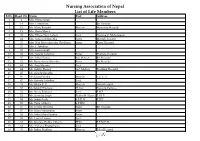

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Achhame, Banke, Chitwan, Kathmandu, and Panchthar Districts

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 44168-012 Capacity Development Technical Assistance (CDTA) October 2013 Nepal: Mainstreaming Climate Change Risk Management in Development (Financed by the Strategic Climate Fund) District Baseline Reports: Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) Achhame, Banke, Chitwan, Kathmandu, and Panchthar Districts Prepared by ICEM – International Centre for Environmental Management This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. MOSTE | Mainstreaming climate change risk management in development | DoLIDAR District Baseline TA – 7984 NEP October, 2013 Mainstreaming Climate Change Risk Management in Development 1 Main Consultancy Package (44768-012) ACHHAM DISTRICT BASELINE: DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT & AGRICULTURAL ROADS (DOLIDAR) Prepared by ICEM – International Centre for Environmental Management METCON Consultants APTEC Consulting Prepared for Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment, Government of Nepal Environment Natural Resources and Agriculture Department, South Asia Department, Asian Development Bank Version B 1 MOSTE | Mainstreaming climate change risk management in development | DoLIDAR District Baseline TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 ACHHAM DISTRICT .......................................................................................................... -

Peasantry in Nepal

92 Chapter 4 Chapter 4 Peasantry in Kathmandu Valley and Its Southern Ridges 4.1 Introduction From ancient times, different societies of caste/ethnicity have been adopting various strategies for ac- quiring a better livelihood in Nepal. Agriculture was, and is, the main strategy. The predominant form of agriculture practised throughout the hilly area of the Nepal is crop farming, livestock and forestry at the subsistence level. Kathmandu valley including Lalitpur district is no exception. The making of handicrafts used to be the secondary occupation in the urban areas of the district. People in the montane and the rural part of the district was more dependent upon the forest resources for subsidiary income. Cutting firewood, making khuwa (solidified concentrated milk cream) and selling them in the cities was also a part of the livelihood for the peasants in rural areas. However, since the past few decades peasants/rural households who depended on subsistence farming have faced greater hardships in earning their livelihoods from farming alone due to rapid population growth and degradation of the natural resource base; mainly land and forest. As a result, they have to look for other alternatives to make living. With the development of local markets and road network, people started to give more emphasis to various nonfarm works as their secondary occupation that would not only support farming but also generate subsidiary cash income. Thus, undertaking nonfarm work has become a main strategy for a better livelihood in these regions. With the introduction of dairy farming along with credit and marketing support under the dairy development policy of the government, small scale peasant dairy farming has flourished in these montane regions. -

District Profile - Kathmandu Valley (As of 10 May 2017) HRRP

District Profile - Kathmandu Valley (as of 10 May 2017) HRRP This district profile outlines the current activities by partner organisations (POs) in post-earthquake recovery and reconstruction. It is based on 4W and secondary data collected from POs on their recent activities pertaining to housing sector. Further, it captures a wide range of planned, ongoing and completed activities within the HRRP framework. For additional information, please refer to the HRRP dashboard. FACTS AND FIGURES Population: 2.5 million1 19 VDCs and 22 municipalities Damage Status - Private Structures Type of housing walls KTM Valley National Mud-bonded bricks/stone 20% 41% Cement-bonded bricks/stone 75% 29% Damage Grade (3-5) 104,337 Other 5% 30% Damage Grade (1-2) 10,061 % of households who own 46% 85% Total 114,3982 their housing unit (Census 2011)1 NEWS & UPDATES 1. Mason Training conducted from 27th April 2017 to 3rd May 2017 at Kageshwori Manahara, Kathmandu was conducted by Baliyo Ghar program of NSET funded by USAID. In total 28 masons were trained 2. The monthly meeting of NRA Lalitpur was conducted at NRA office, Gwarko on May 17, 2017. The main agenda of the meeting was to discuss and updating of the reconstruc- tion activities in the district. The meeting had participation NRA officials, LDO of Lalitpur, DUDBC division head, DLPIU engineers and POs such as Lumanti, OXFAM-GB, EWDE-DKH working in the district in Housing, Community infrastructure, Livelihood, WASH, and WASH. 3. • A general meeting of Kathmandu district was held on May 22, 2017 at District Development Committee office, Kathmandu. -

Nepal: Rural Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Sector Development Project

Resettlement Planning Document Due Diligence Report Resettlement Grant Number: 0093 April 2010 Nepal: Rural Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Sector Development Project Surunga-Sharnamati-Tagandubba-Digalbank Road Sub-Project, Jhapa (0+000-23+704) Prepared by the Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Government of Nepal Ministry of Local Development Office of District Development Committee District Technical Office Jhapa Rural Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Sector Development Program Resettlement Statement Document of Surunga – Sharnamati – Tagandubba – Digalbank Road Sub-project (0+000-23+704) April 2010 Abbreviation ADB Asian Development Bank APs Affected People CDC Compensation Determination Committee CDO Chief District Officer CISC Central Implementation Support Consultant DDC District Development Committee DIST District Implementation Support Team DPO District Project Office DoLIDAR Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads -

Share Holder Details S.N

SHARE HOLDER DETAILS S.N. Share Holder Name Kitta Tax Amt. D-mat No. Contact No. 1 A.S.T Pvt Ltd. 3000 1,468 1301090000198794 051527301,9802921805 2 Aarati Thapa 1000 489 1301450000047583 9851076533 3 Aashish Bhakta Shrestha 100 49 1301370000391631 5541407,9813008733 4 Aashish Thapa 100 49 1301060000957721 9843323282 5 Abishek Prajapati 150 73 1301350000028411 9841278200 6 Achyut Ojha 250 122 1301100000028871 9851066699 7 Adman Singh Basnet 400 196 1301380000127015 9849731123 8 Alok Kumar Gupta 100 49 1301060000080947 9801121638 9 Aman Shakya 100 49 1301370000172659 9843047478 10 Amar Mani Poudel 400 196 1301370000355801 014314367,9841397184 11 Amar Tuladhar 200 98 1301070000014331 4434964,9841463539 12 Ambar Shrestha 50 24 1301020000228269 13 Ambika Devi Ghimire 5000 2,447 1301300000017043 9841203837 14 Amit Paudel 130 64 1301120000785312 9818401100 15 Amit Thapa 500 245 1301100000017063 071506370,9851177995 16 Amita Dangol 200 98 1301040000062767 9841676248 17 Amrit Shrestha 300 147 1301040000038818 014434791,9851224803 18 Ananda Prasad Shah 100 49 1301380000010834 9842841577 19 Ananta Kumar Raut 100 49 1301120000134202 9851167371 20 Anbesh Tiwari 200 98 1301580000023378 5590419,9841551898 21 Anil Pudasaini 70 34 1301300000038551 22 Anil Kumar Subedi 100 49 1301220000015303 9843329797 23 Anil Manandhar 100 49 1301090000089723 4279508,9851026167 24 Anil Thapa 200 98 1301090000038448 9801142576 25 Anish Tuladhar 500 245 1301060000009128 014279815,9841237237 26 Anita Baral Tripathi 200 98 1301180000010121 27 Anita Shrestha 200 98 1301120000828235 -

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

Public Open Spaces in Crisis: Appraisal and Observation from Metropolitan Kathmandu, Nepal

Vol. 13(4), pp. 77-90, October-December, 2020 DOI: 10.5897/JGRP2020.0797 Article Number: B74E25D65143 ISSN 2070-1845 Copyright © 2020 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Journal of Geography and Regional Planning http://www.academicjournals.org/JGRP Full Length Research Paper Public open spaces in Crisis: Appraisal and observation from metropolitan Kathmandu, Nepal Krishna Prasad Timalsina Department of Geography, Trichandra Multiple Campus, Faculty of Humanities and Social Science, Tribhuvan University (TU), Nepal. Received 10 September, 2020; Accepted 13 October, 2020 There is an emerging debate in the literature of urbanism that public open space is in crisis in the cities of developing countries due to the increasing trends of urbanization and in-migration. With the significant growth of the urban population and rapid expansion of the city, the land demand for housing and other infrastructure development is very high. The high rate of urbanization due to which encroachment, high speculation, use change, etc. are the major reasons for decreasing public open spaces. There are many inferences that public open spaces are decreasing in Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC) as Tundikhel; an important public open space located in the heart of Kathmandu is decreasing in its size and has changed in its use over time. At present, KMC does not have a sizable public open space for emergency uses such as evacuation, relief, recovery, and reconstruction during the catastrophic hazards. Analysis of historical imagery and the changing patterns of land use reveal that the decreasing trends of open spaces may lead more vulnerable to the city as it does not have public open space for disaster management in an emergency need. -

D:\2003\Menris\Text\KIRTIPUR Fi

about the organisation ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) is an independent ‘Mountain Learning and Knowledge Centre’ serving the eight countries of the Hindu Kush-Himalayas – Afghanistan , Bangladesh , Bhutan , China , India , Myanmar , Nepal , and Pakistan – and the global mountain community.. Founded in 1983, ICIMOD is based in Kathmandu, Nepal, and brings together a partnership of regional member countries, partner institutions, and donors with a commitment for development action to secure the future of the Hindu Kush-Himalayas. The primary objective of the Centre is to promote the development of an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem and to improve the living standards of mountain populations. GIS for Municipal Planning A Case Study from Kirtipur Municipality Basanta Shrestha Birendra Bajracharya Sushil Pradhan Lokap Rajbhandari International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) Mountain Environment and Natural Resources Information Systems (MENRIS) October 2003 Copyright © 2003 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development All rights reserved Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226 Kathmandu, Nepal ISBN 92 9115 765 1 Editorial Team Jenny Riley (Consultant Editor) A. Beatrice Murray (Editor) Dharma R. Maharjan (Technical Support & Layout) Printed and bound in Nepal by Hill Side Press (P) Ltd. Kathmandu The views and interpretations in this paper are those of the contributor(s). They are not attributable to the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and do not imply the expression of any opinion concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Foreword ICIMOD has been promoting the use of geographic information systems (GIS) technology in the Hindu Kush-Himalayan (HKH) region for many years through its Mountain Environment and Natural Resources Information System (MENRIS) programme. -

Ethnomedicinal Uses of Plants Among the Newar Community of Pharping Village of Kathmandu District, Nepal

ETHNOMEDICINAL USES OF PLANTS AMONG THE NEWAR COMMUNITY OF PHARPING VILLAGE OF KATHMANDU DISTRICT, NEPAL N.P. Balami ABSTRACT The present paper highlights 119 species of plants used as medicine by the Newar community of Pharping village of Kathmandu district. All reported medicinal plants were used for 35 types of diseases like Diabetes, Epilepsy, Fever, Jaundice, Rheumatism and other condition such as incense, spice and flavourant etc. Key words: Ethnomedicine, Newar, Pharping village, Kathmandu district. INTRODUCTION Nepal occupies one third of Himalayas lying at 800 04' to 880 12' E and 260 22' to 300 27' N in meeting point of Central Himalayas and Eastern Himalayas .Nepal has rich floral diversity due to high altitudinal, topographic, climatic and edaphic variations, so that various types of forest are found. The different ethnic groups are traditionally linked to resources available in the forest Ethnobotany refers to the study of the interaction between people and plants (Martin, 1995).There is inseparable interrelationship between the ethnic groups and plants. However due to changing perception of the local people, commercialization and socio-economic transformation of all over the world, it has been observed that the indigenous knowledge on resource use has been degraded (Silori & Rana, 2000). In Nepal, the concept of ethnomedicine has been developed since the late 19th century (1885-1901 A.D). The first book "Chandra-Nighantu regarding medical plants was published by the Royal Nepal Academy in 1969 (2025 B.S.). Later, a number of ethnobotanical studies on different ethnic groups of Nepal have been carried out by different workers (Pandey, 1964; Malla & Shakya, 1968; Adhikari & Shakya, 1977; Sacherer, 1979; Malla & Shakya, 1984-1985; Manandhar, 1985, 1990b, 1994-1995; Shrestha & Pradhan, 1986-1993; Joshi et al.