Fanny Hagin Mayer:1 8 9 9 —1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shaping Darkness in Hyakki Yagyō Emaki

Asian Studies III (XIX), 1 (2015), pp.9–27 Shaping Darkness in hyakki yagyō emaki Raluca NICOLAE* Abstract In Japanese culture, the yōkai, the numinous creatures inhabiting the other world and, sometimes, the boundary between our world and the other, are obvious manifestations of the feeling of fear, “translated” into text and image. Among the numerous emaki in which the yōkai appear, there is a specific type, called hyakki yagyō (the night parade of one hundred demons), where all sorts and sizes of monsters flock together to enjoy themselves at night, but, in the end, are scattered away by the first beams of light or by the mysterious darani no hi, the fire produced by a powerful magical invocation, used in the Buddhist sect Shingon. The nexus of this emakimono is their great number, hyakki, (one hundred demons being a generic term which encompasses a large variety of yōkai and oni) as well as the night––the very time when darkness becomes flesh and blood and starts marching on the streets. Keywords: yōkai, night, parade, painted scrolls, fear Izvleček Yōkai (prikazni, demoni) so v japonski kulturi nadnaravna bitja, ki naseljuje drug svet in včasih tudi mejo med našim in drugim svetom ter so očitno manifestacija občutka strahu “prevedena” v besedila in podobe. Med številnimi slikami na zvitkih (emaki), kjer se prikazni pojavljajo, obstaja poseben tip, ki se imenuje hyakki yagyō (nočna parade stotih demonov), kjer se zberejo pošasti različne vrste in velikosti, da bi uživali v noči, vendar jih na koncu preženejo prvi žarki svetlobe ali skrivnosten darani no hi, ogenj, ki se pojavi z močnim magičnim zaklinjanje in se uporablja pri budistični sekti Shingon. -

2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan

Yoko Tomiyasu 2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan 1 CONTENTS Biographical information .............................................................3 Statement ................................................................................4 Translation.............................................................................. 11 Bibliography and Awards .......................................................... 18 Five Important Titles with English text Mayu to Oni (Mayu & Ogree) ...................................................... 28 Bon maneki (Invitation to the Summer Festival of Bon) ......................... 46 Chiisana Suzuna hime (Suzuna the Little Mountain Godness) ................ 67 Nanoko sensei ga yatte kita (Nanako the Magical Teacher) ................. 74 Mujina tanteiktoku (The Mujina Ditective Agency) ........................... 100 2 © Yoko Tomiyasu © Kodansha Yoko Tomiyasu Born in Tokyo in 1959, Tomiyasu grew up listening to many stories filled with monsters and wonders, told by her grandmother and great aunts, who were all lovers of storytelling and mischief. At university she stud- ied the literature of the Heian period (the ancient Japanese era lasting from the 8th to 12 centuries AD). She was deeply attracted to stories of ghosts and ogres in Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), and fell more and more into the world of traditional folklore. She currently lives in Osaka with her husband and two sons. There was a long era of writing stories that I wanted to read for myself. The origin of my creativity is the desire to write about a wonderous world that children can walk into from their everyday life. I want to write about the strange and mysterious world that I have loved since I was a child. 3 STATEMENT Recommendation of Yoko Tomiyasu for the Hans Christian Andersen Award Akira Nogami editor/critic Yoko Tomiyasu is one of Japan’s most popular Pond).” One hundred copies were printed. It authors and has published more than 120 was 1977 and Tomiyasu was 18. -

Myths & Legends of Japan

Myths & Legends Of Japan By F. Hadland Davis Myths & Legends of Japan CHAPTER I: THE PERIOD OF THE GODS In the Beginning We are told that in the very beginning "Heaven and Earth were not yet separated, and the In and Yo not yet divided." This reminds us of other cosmogony stories. The In and Yo, corresponding to the Chinese Yang and Yin, were the male and female principles. It was more convenient for the old Japanese writers to imagine the coming into being of creation in terms not very remote from their own manner of birth. In Polynesian mythology we find pretty much the same conception, where Rangi and Papa represented Heaven and Earth, and further parallels may be found in Egyptian and other cosmogony stories. In nearly all we find the male and female principles taking a prominent, and after all very rational, place. We are told in theNihongi that these male and female principles "formed a chaotic mass like an egg which was of obscurely defined limits and contained germs." Eventually this egg was quickened into life, and the purer and clearer part was drawn out and formed Heaven, while the heavier element settled down and became Earth, which was "compared to the floating of a fish sporting on the surface of the water." A mysterious form resembling a reed-shoot suddenly appeared between Heaven and Earth, and as suddenly became transformed into a God called Kuni-toko- tachi, ("Land-eternal-stand-of-august-thing"). We may pass over the other divine births until we come to the important deities known as Izanagi and Izanami ("Male-who-invites" and "Female-who-invites"). -

EYE-CANDY-CATALOG-3.Pdf

EyeCandyCustomzus.com Hello. Eye Candy Pigments are mica pigments, which are powders which are typically used as an additive or colorant in applications such as Epoxy, Resin, Lacquer, Automotive Paints, Acrylics, Soap Molds, Art, and Cosmetics, just to name a few. Our pigments are NON-TOXIC, animal friendly, irritant, stain free, and most importantly gentle and Did You safe to your skin. The desire for pigments in these industries are limitless, as Eye Know... Candy pigments are proving to be the perfect solution for those Do-It-Yourselfers looking for a VERY cost effective way to customize their projects. At Eye Candy™ our vision is to create a better everyday experience for the many people who use our products. Our business idea supports this vision by offering The word ‘Mica’ originated the best possible service, selection, quality, and value.” in the Latin language and literally means ‘Crumb’. Eye Candy Pigments were originally being used within the automotive paint industry The mica rock is crushed as an additive for paint shops looking for alternative customization at an affordable and processed through price. This concept proved extremely successful and before long our growth and various stages until it takes popularity crossed over into the construction and craft industry markets. Whether the form of, well, little you’re a “DIY’er” or a business, an artist, woodworker, cosmetologist, soap maker, or crumbs. Just in case you automotive painter, we assure you that we have your best interests in mind when it were wondering! comes to our pigments and your projects. What’s the Use?.. -

Japanese Folk Tale

The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale Copublished with Asian Folklore Studies YANAGITA KUNIO (1875 -1962) The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale Translated and Edited by FANNY HAGIN MAYER INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington This volume is a translation of Nihon mukashibanashi meii, compiled under the supervision of Yanagita Kunio and edited by Nihon Hoso Kyokai. Tokyo: Nihon Hoso Shuppan Kyokai, 1948. This book has been produced from camera-ready copy provided by ASIAN FOLKLORE STUDIES, Nanzan University, Nagoya, japan. © All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nihon mukashibanashi meii. English. The Yanagita Kunio guide to the japanese folk tale. "Translation of Nihon mukashibanashi meii, compiled under the supervision of Yanagita Kunio and edited by Nihon Hoso Kyokai." T.p. verso. "This book has been produced from camera-ready copy provided by Asian Folklore Studies, Nanzan University, Nagoya,japan."-T.p. verso. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Tales-japan-History and criticism. I. Yanagita, Kunio, 1875-1962. II. Mayer, Fanny Hagin, 1899- III. Nihon Hoso Kyokai. IV. Title. GR340.N52213 1986 398.2'0952 85-45291 ISBN 0-253-36812-X 2 3 4 5 90 89 88 87 86 Contents Preface vii Translator's Notes xiv Acknowledgements xvii About Folk Tales by Yanagita Kunio xix PART ONE Folk Tales in Complete Form Chapter 1. -

TABLE of CONTENTS, PART I Introduction 1 How to Use The

TABLE OF CONTENTS, PART I Introduction 1 How to Use the Manual 1 Explanation of an Entry in the Romaji Section 2 Explanation of a Page in the Japanese Section 5 Explanation of an Entry in the Japanese Section 5 Romaji Section 7 Index by Readings of Kanji Characters 93 TABLE OF CONTENTS, PART II Japanese Section 1 INTRODUCTION This manual is mainly for the purpose of practicing the writing and reading of Japanese, in particular of kanji characters. This volume of the manual, Volume I, is divided in two parts and consists essentially of two sections, a romaji section (in Part I) where readings of sample Japanese words are presented in romaji, and a Japanese section (in Part II) where most of the same sample words are presented in printed Japanese, that is, in terms of kanji and kana characters in their printed form. The two sections are divided equally into groups, one per page. Each group in either section is made up of numbered entries, each entry addressing a specific kanji character. Given a group in the romaji section, say the fifth group, then the entries in this group address in the same order exactly the same set of kanji characters addressed by the entries in the fifth group in the Japanese section. Given an entry in a group (romaji or Japanese), it addresses one and only one kanji character in terms of one or two sets of sample words that contain the character when written in Japanese. If the entry is in the romaji section, one set contains, if any, readings (in romaji) of sample words with ON readings of the character. -

Alternative Titles Index

VHD Index - 02 9/29/04 4:43 PM Page 715 Alternative Titles Index While it's true that we couldn't include every Asian cult flick in this slim little vol- ume—heck, there's dozens being dug out of vaults and slapped onto video as you read this—the one you're looking for just might be in here under a title you didn't know about. Most of these films have been released under more than one title, and while we've done our best to use the one that's most likely to be familiar, that doesn't guarantee you aren't trying to find Crippled Avengers and don't know we've got it as The Return of the 5 Deadly Venoms. And so, we've gathered as many alternative titles as we can find, including their original language title(s), and arranged them in alphabetical order in this index to help you out. Remember, English language articles ("a", "an", "the") are ignored in the sort, but foreign articles are NOT ignored. Hey, my Japanese is a little rusty, and some languages just don't have articles. A Fei Zheng Chuan Aau Chin Adventure of Gargan- Ai Shang Wo Ba An Zhan See Days of Being Wild See Running out of tuas See Gimme Gimme See Running out of (1990) Time (1999) See War of the Gargan- (2001) Time (1999) tuas (1966) A Foo Aau Chin 2 Ai Yu Cheng An Zhan 2 See A Fighter’s Blues See Running out of Adventure of Shaolin See A War Named See Running out of (2000) Time 2 (2001) See Five Elements of Desire (2000) Time 2 (2001) Kung Fu (1978) A Gai Waak Ang Kwong Ang Aau Dut Air Battle of the Big See Project A (1983) Kwong Ying Ji Dut See The Longest Nite The Adventures of Cha- Monsters: Gamera vs. -

Exploring the Macabre, Malevolent, and Mysterious

Exploring the Macabre, Malevolent, and Mysterious Exploring the Macabre, Malevolent, and Mysterious: Multidisciplinary Perspectives Edited by Matthew Hodge and Elizabeth Kusko Exploring the Macabre, Malevolent, and Mysterious: Multidisciplinary Perspectives Edited by Matthew Hodge and Elizabeth Kusko This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Matthew Hodge, Elizabeth Kusko and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5769-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5769-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ............................................................................................ vii List of Figures.......................................................................................... viii Preface ....................................................................................................... ix Part One: History and Culture Chapter One ................................................................................................ 2 Modernizing and Marketing Monsters in Japan: Shapeshifting Yōkai and the Reflection of Culture Kendra Sheehan Chapter Two ............................................................................................ -

ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA No. 29

Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures Polish Academy of Sciences ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA No. 29 Warszawa 2016 Editor-in-Chief Board of Advisory Editors KRZYSZTOF TRZCIŃSKI NGUYEN QUANG THUAN KENNETH OLENIK Subject Editor ABDULRAHMAN AL-SALIMI OLGA BARBASIEWICZ JOLANTA SIERAKOWSKA-DYNDO English Text Consultant BOGDAN SKŁADANEK ANNA KOSTKA LEE MING-HUEI ZHANG HAIPENG French Text Consultant NICOLAS LEVI Secretary AGNIESZKA PAWNIK © Copyright by Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 2016 PL ISSN 0860–6102 eISSN 2449–8653 ISBN 978–83–7452–091–1 ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA is abstracted in The Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Index Copernicus, ProQuest Database Contents ARTICLES: MAXIME DANESIN, L’aube des light novels en France ..... 7 MÁRIA ILDIKÓ FARKAS, Reconstructing Tradition. The Debate on “Invented Tradition” in the Japanese Modernization ............................................................................................... 31 VERONICA GASPAR, Reassessing the Premises of the Western Musical Acculturation in Far-East Asia .................. 47 MARIA GRAJDIAN, Imaginary Nostalgia: The Poetics and Pragmatics of Escapism in Late Modernity as Represented by Satsuki & Mei’s House on the EXPO 2005 Site ................... 59 MAYA KELIYAN, Japanese Local Community as Socio- Structural Resource for Ecological Lifestyle ........................ 85 EKATERINA LEVCHENKO, Rhetorical Devices in Old Japanese Verse: Structural Analysis and Semantics........... -

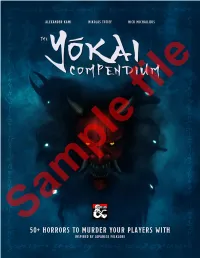

The Yōkai Compendium

Sample file FROM THE CREATORS OF & COMES ō Sample file Table of Contents Shirime . 36 Introduction 3 Suiko . 37 Tanuki . 38 Bestiary Bake-danuki . 38 Abura Sumashi . 4 Fukuro Mujina . 38 Akabeko . 5 Korōri . 38 Akaname . 6 Tengu . 40 Ama . 7 Daitengu . 40 Amahime . 7 Kotengu . 41 Amarie . 8 Tennin . 42 Baku . 9 Tsuchigumo . 43 Chirizuka . 10 Tsuchinoko . 44 Hashihime . 11 Tsukumogami . 45 A Hashihime's Lair . 12 Abumi Guchi . 45 Hinowa . 13 Chōchin Obake . 45 Kata-waguruma . 13 Jatai . 45 Wanyūdō . 14 Kasa Obake . 45 Itsumade . 15 Kyōrinrin . 45 Jorōgumo . 16 Shiro Uneri . 45 Kappa . 17 Shōgorō . 45 Kitsune . 18 Zorigami . 45 Ashireiko . 18 Ubume . 51 Chiko . 18 Umibōzu . 52 Kiko . 19 Ushi-oni . 53 Tenko . 20 An Ushi-oni's Lair . 53 Kūko . 21 Kurote . 22 Sorted Creatures 54 Ningyo . 23 Creatures by CR . 54 Nurikabe . 24 Creatures by Terrain . 55 Ōmukade . 25 Creatures by Type . 57 Oni . 27 Pronunciation & Translation Table . 58 Amanojaku . 27 Dodomeki . 28 Hannya . .. -

A Gazetteer of Myoshima

A Gazetteer of Myoshima Agathokles September 2, 2007 Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Motivation ...................................... ........ 4 1.2 ChallengesandInspirations . .............. 4 1.3 Sources ......................................... ....... 5 1.3.1 OD&DSourcebooks ............................... ...... 5 1.3.2 AD&DSourcebooks ............................... ...... 5 1.3.3 DragonMagazine................................ ....... 5 1.3.4 OD&DFanResources .............................. ...... 5 1.3.5 OrientalAdventuresLine . .......... 5 1.3.6 LiteratureandAnime . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ........ 6 2 History of Myoshima 7 2.1 TimelineofPatera ................................ .......... 7 2.1.1 Prehistory.................................... ....... 7 2.1.2 TheGreatRainofFire ............................ ....... 8 2.1.3 RiseofGreatHouses............................. ........ 8 2.1.4 TheKamakuraShogunate. ........ 9 2.1.5 ThreeHundredYearsWar. ........ 9 2.1.6 RiseoftheMyoshimanEmpire . ......... 10 2.1.7 TimeofRetreat ................................. ...... 11 2.1.8 TheModernAge.................................. ..... 12 2.2 TheBloodlinesandtheNineGreatHouses . .............. 14 2.2.1 HouseYouseihito............................... ........ 14 2.2.2 HouseSennyo................................... ...... 14 2.2.3 HouseHanejishi ................................ ....... 15 2.2.4 HouseNueteki .................................. ...... 16 2.2.5 HouseRyuuko ................................... ..... 16 2.2.6 HouseShishikugi .............................. -

In Search for Chimeras: Three Hybrids of Japanese Imagination

IN SEARCH FOR CHIMERAS: THREE HYBRIDS OF JAPANESE IMAGINATION Raluca Nicolae [email protected] Abstract: In Greek mythology, the chimera was a monstrous creature, composed of the parts of multiple animals. Later, the name has come to be applied to any fantastic or horrible creation of the imagination, and also to a hybrid plant of mixed characteristics. In addition, the Japanese folklore has also produced examples of such an imaginative hybridization, such as Nue, Baku, Raijū. Nue is a legendary creature with the head of a monkey, the body of a raccoon dog, the legs of a tiger, and a snake like tail. It was killed by Minamoto no Yorimasa as the monster was draining the emperor out of energy, causing him a terrible illness. Baku is a spirit who devours dreams and is sometimes depicted as a supernatural being with an elephant’s trunk, rhinoceros eyes, an ox tail, and tiger paws. In China it was believed that sleeping on a Baku pelt could protect a person from pestilence and its image was a powerful talisman against the evil. Raijū (lit. “the thunder animal”) was a legendary creature whose body looked like a cat, a raccoon dog, monkey or weasel. Raijū appeared whenever a thunder struck, scratching the ground with animal like claws. The above mentioned examples indicate that monsters are not mere just metaphors of beastliness. Their veneration as well as rejection form the very the image of the numinous stark dualism: mysterium tremendum et fascinans (“fearful and fascinating mystery”) – as coined by Rudolf Otto. Keywords: chimera; hybrid; Nue; Baku; Raijū; yōkai; Japanese folklore.