ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA No. 29

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cobra the Animation Review

Cobra the animation review [Review] Cobra: The Animation. by Gerald Rathkolb October 12, SHARE. Sometimes, it's refreshing to find something that has little concern with following. May 27, Title: Cobra the Animation Genre: Action/Adventure Company: Magic Bus Format: 12 episodes Dates: 2 Jan to 27 Mar Synopsis: Cobra. Space Adventure Cobra is a hangover from the 80's. it isn't reproduced in this review simply because the number of zeros would look silly. Get ready to blast off, rip-off, and face-off as the action explodes in COBRA THE ANIMATION! The Review: Audio: The audio presentation for. Cobra The Animation – Blu-ray Review. written by Alex Harrison December 5, Sometimes you get a show that is fun and captures people's imagination. visits a Virtual Reality parlor to live out his vague male fantasies, but the experience instead revives memories of being the great space rogue Cobra, scourge of. Here's a quick review. I think that my biggest issue with Cobra is that I unfortunately happened to watch one of the worst Cobra episodes as my. A good reviewer friend of mine, Andrew Shelton at the Anime Meta-Review, has a It's a rating I wish I had when it came to shows like Space Adventure Cobra. Cobra Anime Anthology ?list=PLyldWtGPdps0xDpxmZ95AMcS4wzST1qkq. Not quite a full review, just a quick look at the new Space Adventure Cobra tv series (aka Cobra: the Animation. This isn't always the case though. Sometimes you wonder this same thing about series that are actually good, such as Cobra the Animation. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Shaping Darkness in Hyakki Yagyō Emaki

Asian Studies III (XIX), 1 (2015), pp.9–27 Shaping Darkness in hyakki yagyō emaki Raluca NICOLAE* Abstract In Japanese culture, the yōkai, the numinous creatures inhabiting the other world and, sometimes, the boundary between our world and the other, are obvious manifestations of the feeling of fear, “translated” into text and image. Among the numerous emaki in which the yōkai appear, there is a specific type, called hyakki yagyō (the night parade of one hundred demons), where all sorts and sizes of monsters flock together to enjoy themselves at night, but, in the end, are scattered away by the first beams of light or by the mysterious darani no hi, the fire produced by a powerful magical invocation, used in the Buddhist sect Shingon. The nexus of this emakimono is their great number, hyakki, (one hundred demons being a generic term which encompasses a large variety of yōkai and oni) as well as the night––the very time when darkness becomes flesh and blood and starts marching on the streets. Keywords: yōkai, night, parade, painted scrolls, fear Izvleček Yōkai (prikazni, demoni) so v japonski kulturi nadnaravna bitja, ki naseljuje drug svet in včasih tudi mejo med našim in drugim svetom ter so očitno manifestacija občutka strahu “prevedena” v besedila in podobe. Med številnimi slikami na zvitkih (emaki), kjer se prikazni pojavljajo, obstaja poseben tip, ki se imenuje hyakki yagyō (nočna parade stotih demonov), kjer se zberejo pošasti različne vrste in velikosti, da bi uživali v noči, vendar jih na koncu preženejo prvi žarki svetlobe ali skrivnosten darani no hi, ogenj, ki se pojavi z močnim magičnim zaklinjanje in se uporablja pri budistični sekti Shingon. -

Henry and Nancy Rosin Collection of Early Photography of Japan

Henry and Nancy Rosin Collection of Early Photography of Japan Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives Washington, D.C. 20013 [email protected] https://www.freersackler.si.edu/research/archives/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Local Numbers................................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series FSA A1999.35 A1: Photo album from the studio of Adolpho Farsari, [1860 - ca. 1900]................................................................................................................... 3 Series FSA A1999.35 A2: Photo album from the studio of Tamamura, [1860 - ca. 1900]...................................................................................................................... -

Titolo Anno Paese

compensi "copia privata" per l'anno 2018 (*) Per i film esteri usciti in Italia l’anno corrisponde all’anno di importazione titolo anno paese #SCRIVIMI ANCORA (LOVE, ROSIE) 2014 GERMANIA '71 2015 GRAN BRETAGNA (S) EX LIST ((S) LISTA PRECEDENTE) (WHAT'S YOUR NUMBER?) 2011 USA 002 OPERAZIONE LUNA 1965 ITALIA/SPAGNA 007 - IL MONDO NON BASTA (THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH) 2000 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 BERSAGLIO MOBILE (A VIEW TO A KILL) 1985 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 DOMANI NON MUORE MAI (IL) (TOMORROW NEVER DIES) 1997 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 SOLO PER I TUOI OCCHI (FOR YOUR EYES ONLY) 1981 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 VENDETTA PRIVATA (LICENCE TO KILL) 1989 USA 007 ZONA PERICOLO (THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS) 1987 GRAN BRETAGNA 10 CLOVERFIELD LANE 2016 USA 10 REGOLE PER FARE INNAMORARE 2012 ITALIA 10 YEARS - (DI JAMIE LINDEN) 2011 USA 10.000 A.C. (10.000 B.C.) 2008 USA 10.000 DAYS - 10,000 DAYS (DI ERIC SMALL) 2014 USA 100 DEGREES BELOW ZERO - 100 GRADI SOTTO ZERO 2013 USA 100 METRI DAL PARADISO 2012 ITALIA 100 MILLION BC 2012 USA 100 STREETS (DI JIM O'HANLON) 2016 GRAN BRETAGNA 1000 DOLLARI SUL NERO 1966 ITALIA/GERMANIA OCC. 11 DONNE A PARIGI (SOUS LES JUPES DES FILLES) 2015 FRANCIA 11 SETTEMBRE: SENZA SCAMPO - 9/11 (DI MARTIN GUIGUI) 2017 CANADA 11.6 - THE FRENCH JOB (DI PHILIPPE GODEAU) 2013 FRANCIA 110 E FRODE (STEALING HARVARD) 2003 USA 12 ANNI SCHIAVO (12 YEARS A SLAVE) 2014 USA 12 ROUND (12 ROUNDS) 2009 USA 12 ROUND: LOCKDOWN - (DI STEPHEN REYNOLDS) 2015 USA 120 BATTITI AL MINUTO (120 BETTEMENTS PAR MINUTE) 2017 FRANCIA 127 ORE (127 HOURS) 2011 USA 13 2012 USA 13 HOURS (13 HOURS: -

Download the Program (PDF)

ヴ ィ ボー ・ ア ニ メー シ カ ョ ワ ン イ フ イ ェ と ス エ ピ テ ッ ィ Viborg クー バ AnimAtion FestivAl ル Kawaii & epikku 25.09.2017 - 01.10.2017 summAry 目次 5 welcome to VAF 2017 6 DenmArk meets JApAn! 34 progrAmme 8 eVents Films For chilDren 40 kAwAii & epikku 8 AnD families Viborg mAngA AnD Anime museum 40 JApAnese Films 12 open workshop: origAmi 42 internAtionAl Films lecture by hAns DybkJær About 12 important ticket information origAmi 43 speciAl progrAmmes Fotorama: 13 origAmi - creAte your own VAF Dog! 44 short Films • It is only possible to order tickets for the VAF screenings via the website 15 eVents At Viborg librAry www.fotorama.dk. 46 • In order to pick up a ticket at the Fotorama ticket booth, a prior reservation Films For ADults must be made. 16 VimApp - light up Viborg! • It is only possible to pick up a reserved ticket on the actual day the movie is 46 JApAnese Films screened. 18 solAr Walk • A reserved ticket must be picked up 20 minutes before the movie starts at 50 speciAl progrAmmes the latest. If not picked up 20 minutes before the start of the movie, your 20 immersion gAme expo ticket order will be annulled. Therefore, we recommended that you arrive at 51 JApAnese short Films the movie theater in good time. 22 expAnDeD AnimAtion • There is a reservation fee of 5 kr. per order. 52 JApAnese short Film progrAmmes • If you do not wish to pay a reservation fee, report to the ticket booth 1 24 mAngA Artist bAttle hour before your desired movie starts and receive tickets (IF there are any 56 internAtionAl Films text authors available.) VAF sum up: exhibitions in Jane Lyngbye Hvid Jensen • If you wish to see a movie that is fully booked, please contact the Fotorama 25 57 Katrine P. -

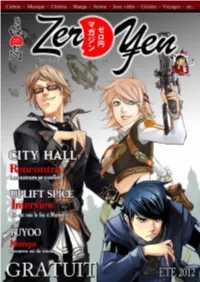

Zero Yen 003 Secure.Pdf

Toute l’équipe de Zero Yen ... EDITO Une fois n’est pas coutume, nous avons à peu près réussi à tenir nos délais d’impres- sion et vous voilà donc en possession de notre troisième opus fraîchement imprimé ... vous souhaite de bonnes vacances. pour la Japan Expo. Autant dire que nous misons gros sur cet événement pour prêcher la bonne parole hors de nos belles frontières marseillaises et faire le plein de nouveaux Rédacteur en chef : Sébastien PASTOR amis. Responsable graphique : Hugo COPPONI Traduction : Kokoro YAMAMICHI Rédacteurs : Sébastien PASTOR, Ghis VANNINI, Xavier Pas d’énormes changements dans ce numéro si ce n’est que, pour une fois, une de CALTAGIRONE, Kokoro YAMAMICHI, Gilles ERMIA, nos couvertures ne sera pas consacrée à un groupe japonais. « Quoi ? Comment ? Cédric LEVY C’est un scandale ! » crieront certains. Pour les autres, ils se délecteront sans doute Logo : Stéphan LUTAS de l’excellente interview des auteurs de City Hall que nous avons réalisée il y a peu. Correction : Ghis VANNINI, Farid HALLALET À la rédaction, nous avons l’esprit ouvert, et même si cette BD ne vient pas du pays Photos de couvertures : du Soleil-Levant, il nous paraissait évident qu’il fallait vous présenter cette œuvre de CITY HALL : © 2012 Ankama qualité. Autre petit cadeau, nous vous proposons un poster d’Uplift Spice en page cen- UPLIFT SPICE : © 2012 GROWING UP Inc. All Rights Reserved. Poster central : trale. Je vous imagine déjà l’afficher fièrement dans votre chambre entre une affiche de UPLIFT SPICE : © Hugo Copponi @ Zero Yen Media David Hasselhoff et une photo dédicacée de Chantal Goya. -

2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan

Yoko Tomiyasu 2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan 1 CONTENTS Biographical information .............................................................3 Statement ................................................................................4 Translation.............................................................................. 11 Bibliography and Awards .......................................................... 18 Five Important Titles with English text Mayu to Oni (Mayu & Ogree) ...................................................... 28 Bon maneki (Invitation to the Summer Festival of Bon) ......................... 46 Chiisana Suzuna hime (Suzuna the Little Mountain Godness) ................ 67 Nanoko sensei ga yatte kita (Nanako the Magical Teacher) ................. 74 Mujina tanteiktoku (The Mujina Ditective Agency) ........................... 100 2 © Yoko Tomiyasu © Kodansha Yoko Tomiyasu Born in Tokyo in 1959, Tomiyasu grew up listening to many stories filled with monsters and wonders, told by her grandmother and great aunts, who were all lovers of storytelling and mischief. At university she stud- ied the literature of the Heian period (the ancient Japanese era lasting from the 8th to 12 centuries AD). She was deeply attracted to stories of ghosts and ogres in Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), and fell more and more into the world of traditional folklore. She currently lives in Osaka with her husband and two sons. There was a long era of writing stories that I wanted to read for myself. The origin of my creativity is the desire to write about a wonderous world that children can walk into from their everyday life. I want to write about the strange and mysterious world that I have loved since I was a child. 3 STATEMENT Recommendation of Yoko Tomiyasu for the Hans Christian Andersen Award Akira Nogami editor/critic Yoko Tomiyasu is one of Japan’s most popular Pond).” One hundred copies were printed. It authors and has published more than 120 was 1977 and Tomiyasu was 18. -

Subculture As Social Knowledge: a Hopeful Reading of Otaku Culture

DE GRUYTER Contemporary Japan 2016; 28(1): 33–57 Open Access Brett Hack* Subculture as social knowledge: a hopeful reading of otaku culture DOI 10.1515/cj-2016-0003 Abstract: This essay analyzes Japan’s otaku subculture using Hirokazu Miya- zaki’s (2006) definition of hope as a “reorientation of knowledge.” Erosion of postwar social systems has tended to instill a sense of hopelessness among many Japanese youth. Hopelessness manifests as two analogous kinds of refus- al: individual social withdrawal and recourse to solipsistic neonationalist ideol- ogy. Previous analyses of otaku have demonstrated its connections with these two reactions. Here, I interrogate otaku culture’s relationship to neonationalism by investigating its interaction with the xenophobic online subculture known as the netto uyoku. Characterizing both subcultures as discursive practices, I argue that the similarity between netto uyoku and otaku is not one of identity but one of method. Netto uyoku discourse serves to perform an imagined na- tionalist persona. While otaku elements can be incorporated into netto uyoku performance, other net users invoke the otaku faculty of parody to highlight the constructed nature of netto uyoku identity through ironic recontextualiza- tion. This application of otaku principles enables a description of otaku culture as a form of social knowledge, reoriented here to defuse the climate of hope- lessness purveyed by the netto uyoku. In the final section, I offer examples of subcultural knowledge being applied to national and international issues in order to indicate its further potential as a source of enabling hope for Japanese youth. Keywords: otaku, subculture, nationalism, Internet, media studies, Japanese studies, cultural studies 1 Introduction This essay investigates social orientations within Japanese subcultures accord- ing to anthropologist Hirokazu Miyazaki’s (2006: 160) definition of hope as a * Corresponding author: Brett Hack, Aichi Prefectural University, E-mail: [email protected] © 2016 Brett Hack, licensee De Gruyter. -

Myths & Legends of Japan

Myths & Legends Of Japan By F. Hadland Davis Myths & Legends of Japan CHAPTER I: THE PERIOD OF THE GODS In the Beginning We are told that in the very beginning "Heaven and Earth were not yet separated, and the In and Yo not yet divided." This reminds us of other cosmogony stories. The In and Yo, corresponding to the Chinese Yang and Yin, were the male and female principles. It was more convenient for the old Japanese writers to imagine the coming into being of creation in terms not very remote from their own manner of birth. In Polynesian mythology we find pretty much the same conception, where Rangi and Papa represented Heaven and Earth, and further parallels may be found in Egyptian and other cosmogony stories. In nearly all we find the male and female principles taking a prominent, and after all very rational, place. We are told in theNihongi that these male and female principles "formed a chaotic mass like an egg which was of obscurely defined limits and contained germs." Eventually this egg was quickened into life, and the purer and clearer part was drawn out and formed Heaven, while the heavier element settled down and became Earth, which was "compared to the floating of a fish sporting on the surface of the water." A mysterious form resembling a reed-shoot suddenly appeared between Heaven and Earth, and as suddenly became transformed into a God called Kuni-toko- tachi, ("Land-eternal-stand-of-august-thing"). We may pass over the other divine births until we come to the important deities known as Izanagi and Izanami ("Male-who-invites" and "Female-who-invites").