The Function of Manga to Shape and Reflect Japanese Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cobra the Animation Review

Cobra the animation review [Review] Cobra: The Animation. by Gerald Rathkolb October 12, SHARE. Sometimes, it's refreshing to find something that has little concern with following. May 27, Title: Cobra the Animation Genre: Action/Adventure Company: Magic Bus Format: 12 episodes Dates: 2 Jan to 27 Mar Synopsis: Cobra. Space Adventure Cobra is a hangover from the 80's. it isn't reproduced in this review simply because the number of zeros would look silly. Get ready to blast off, rip-off, and face-off as the action explodes in COBRA THE ANIMATION! The Review: Audio: The audio presentation for. Cobra The Animation – Blu-ray Review. written by Alex Harrison December 5, Sometimes you get a show that is fun and captures people's imagination. visits a Virtual Reality parlor to live out his vague male fantasies, but the experience instead revives memories of being the great space rogue Cobra, scourge of. Here's a quick review. I think that my biggest issue with Cobra is that I unfortunately happened to watch one of the worst Cobra episodes as my. A good reviewer friend of mine, Andrew Shelton at the Anime Meta-Review, has a It's a rating I wish I had when it came to shows like Space Adventure Cobra. Cobra Anime Anthology ?list=PLyldWtGPdps0xDpxmZ95AMcS4wzST1qkq. Not quite a full review, just a quick look at the new Space Adventure Cobra tv series (aka Cobra: the Animation. This isn't always the case though. Sometimes you wonder this same thing about series that are actually good, such as Cobra the Animation. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

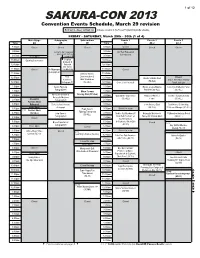

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

History 146C: a History of Manga Fall 2019; Monday and Wednesday 12:00-1:15; Brighton Hall 214

History 146C: A History of Manga Fall 2019; Monday and Wednesday 12:00-1:15; Brighton Hall 214 Insufficient Direction, by Moyoco Anno This syllabus is subject to change at any time. Changes will be clearly explained in class, but it is the student’s responsibility to stay abreast of the changes. General Information Prof. Jeffrey Dym http://www.csus.edu/faculty/d/dym/ Office: Tahoe 3088 e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Mondays 1:30-3:00, Tuesdays & Thursdays 10:30-11:30, and by appointment Catalog Description HIST 146C: A survey of the history of manga (Japanese graphic novels) that will trace the historical antecedents of manga from ancient Japan to today. The course will focus on major artists, genres, and works of manga produced in Japan and translated into English. 3 units. GE Area: C-2 1 Course Description Manga is one of the most important art forms to emerge from Japan. Its importance as a medium of visual culture and storytelling cannot be denied. The aim of this course is to introduce students and to expose students to as much of the history and breadth of manga as possible. The breadth and scope of manga is limitless, as every imaginable genre exists. With over 10,000 manga being published every year (roughly one third of all published material in Japan), there is no way that one course can cover the complete history of manga, but we will cover as much as possible. We will read a number of manga together as a class and discuss them. -

BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019

BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BANDAI NAMCO Group Outline 3 Related Market Data Group Organization Toys and Hobby 01 Overview of Group Organization 20 Toy Market 21 Plastic Model Market Results of Operations Figure Market 02 Consolidated Business Performance Capsule Toy Market Management Indicators Card Product Market 03 Sales by Category 22 Candy Toy Market Children’s Lifestyle (Sundries) Market Products / Service Data Babies’ / Children’s Clothing Market 04 Sales of IPs Toys and Hobby Unit Network Entertainment 06 Network Entertainment Unit 22 Game App Market 07 Real Entertainment Unit Top Publishers in the Global App Market Visual and Music Production Unit 23 Home Video Game Market IP Creation Unit Real Entertainment 23 Amusement Machine Market 2 BANDAI NAMCO Group’s History Amusement Facility Market History 08 BANDAI’s History Visual and Music Production NAMCO’s History 24 Visual Software Market 16 BANDAI NAMCO Group’s History Music Content Market IP Creation 24 Animation Market Notes: 1. Figures in this report have been rounded down. 2. This English-language fact book is based on a translation of the Japanese-language fact book. 1 BANDAI NAMCO Group Outline GROUP ORGANIZATION OVERVIEW OF GROUP ORGANIZATION Units Core Company Toys and Hobby BANDAI CO., LTD. Network Entertainment BANDAI NAMCO Entertainment Inc. BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. Real Entertainment BANDAI NAMCO Amusement Inc. Visual and Music Production BANDAI NAMCO Arts Inc. IP Creation SUNRISE INC. Affiliated Business -

Manga Vision: Cultural and Communicative Perspectives / Editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, Manga Artist

VISION CULTURAL AND COMMUNICATIVE PERSPECTIVES WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL MANGA VISION MANGA VISION Cultural and Communicative Perspectives EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN © Copyright 2016 Copyright of this collection in its entirety is held by Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou and Cathy Sell. Copyright of manga artwork is held by Queenie Chan, unless another artist is explicitly stated as its creator in which case it is held by that artist. Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the respective author(s). All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/mv-9781925377064.html Series: Cultural Studies Design: Les Thomas Cover image: Queenie Chan National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Manga vision: cultural and communicative perspectives / editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, manga artist. ISBN: 9781925377064 (paperback) 9781925377071 (epdf) 9781925377361 (epub) Subjects: Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects--Japan. Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects. Comic books, strips, etc., in art. Comic books, strips, etc., in education. -

Stepping on Roses: V

STEPPING ON ROSES: V. 3 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rinko Ueda | 208 pages | 09 Dec 2010 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421532370 | English | San Francisco, United States Stepping on Roses: v. 3 PDF Book I bet the author got a new assistant. Rinko Ueda. His frustration and confusion with how Sumi is basically a prisoner to Soichiro but still loves him.. Shueisha Bessatsu Margaret Ribon. January [14]. Next time I will be more careful with the manga I buy. He's gone through two very dramatic shifts, and the only thing I'm left to conclude is that he's a psychopath. Welcome back. April 24, [13]. However, I am a little worried at the way the 2 men in this love triangle are behaving. The man says that he will take away all of Sumi's younger siblings and sell them into slavery. On the one hand i love the characters and other find them annoying a strange combination that kept me reading onward. The place was already burning and yet that crazy guy said "In the next world.. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Comics Manga. Rating details. View all 4 comments. This just keeps on getting better! Soichiro seems to be warming up to Sumi - he let her change his bandages and stuff. Also, the spread of Sumi lying with thorns and flowers About Rinko Ueda. Despite his terror regarding fire, he rescued Sumi and Nozomu from that inn fire. May 24, [19]. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. -

Cross-Dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media Sheena Marie Woods University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2015 The aF scination of Manga: Cross-dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media Sheena Marie Woods University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Japanese Studies Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Theatre History Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Woods, Sheena Marie, "The asF cination of Manga: Cross-dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1273. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 44 The Fascination of Manga: Cross-dressing and Gender Performativity in Japanese Media A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies By Sheena Woods University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in International Relations, 2012 University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in Asian Studies, 2012 July 2015 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _______________________ Dr. Elizabeth Markham Thesis Director ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Tatsuya Fukushima Dr. Rembrandt Wolpert Committee Member Committee Member 4 4 Abstract The performativity of gender through cross-dressing has been a staple in Japanese media throughout the centuries. This thesis engages with the pervasiveness of cross-dressing in popular Japanese media, from the modern shōjo gender-bender genre of manga and anime to the traditional Japanese theatre. -

The Viewing Mind and Live-Action Japanese Television Series: a Cognitive Perspective on Gender Constructions in Seirei No Moribito (Guardian of the Spirit)

NARRATIVES / AESTHETICS / CRITICISM THE VIEWING MIND AND LIVE-ACTION JAPANESE TELEVISION SERIES: A COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE ON GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS IN SEIREI NO MORIBITO (GUARDIAN OF THE SPIRIT) HELEN KILPATRICK Name Helen Kilpatrick clever narrative strategies which operate to maintain viewer Academic centre University of Wollongong, Australia interest and produce affective engagement with gendered E-mail address [email protected] positionings. A cognitive narratological exploration of these story-telling devices and the scripts and schemas KEYWORDS they conjure helps demonstrate how the series operates Japanese television; gender; narrative strategies; cognitive affectively to deconstruct dominant patriarchal ideologies. processing; Moribito. This examination explores how narrative techniques prompt viewer mental processing with regard to cultural schemas ABSTRACT and scripts of, for instance, male/female roles in family The recent (2016–2018) live-action Japanese television relationships, women’s participation in the employment series, Seirei no Moribito (Guardian of the Spirit), was sector, and marriage and childbearing. A close analysis of produced by NHK in the vein of the taiga (big river) historical the filmic strategies and devices which encourage audience drama, but challenges this and other Japanese generic engagement with the main female protagonist, Balsa, and and cultural conventions. It does so not only through its her relationships casts light on the state of some of the production as a fantasy series or its warrior heroine rather changing attitudes to gendered social and personal roles in than the usual masculine samurai hero, but also through the context of recent and topical social discourse in Japan. 25 SERIES VOLUME V, Nº 2, WINTER 2019: 25-44 DOI https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2421-454X/9334 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TV SERIAL NARRATIVES ISSN 2421-454X SERIALS IN EAST ASIA NARRATIVES / AESTHETICS / CRITICISM > HELEN KILPATRICK THE VIEWING MIND AND LIVE-ACTION JAPANESE TELEVISION SERIES 0. -

Introduction: Girls' Aesthetics

Notes Introduction: Girls’ Aesthetics 1. In Japanese names, family names come before given names. I follow this order in this book, except for individuals who publish their writings in English. 2. To be precise, it started as shō nen-ai manga. The differences between shō nen-ai manga and BL manga are detailed in Chapter 2. 3. Adult males were granted suffrage in 1925. 4. The postwar constitution of Japan declares eternal renunciation of war, and the Self-Defense Forces are supposed to only defend the Japanese land and people in cases of foreign attack. However, their status is ambivalent, demonstrated in their involvement in the Gulf and Iraq Wars, for exam- ple. For more discussions on the Self-Defense Forces, see Chapter 3. 5. I translated all of the Japanese titles except those that were previously translated into English. 6. See Driscoll’s book Girls: Feminine Adolescence in Popular Culture and Cultural Theory (2002). 7. The term “lesbian” started to be used in Japan in the 1950s. At this early stage, it was pronounced “resubian,” not “rezubian” like it is now. This is because, as Akaeda Kanako reports based on her extensive archival research, the term was initially introduced in relation to French culture and the terms lesbien and lesbienne (2014: 138–42). 8. For more details, see Miyadai Shinji’s Choice of Girls in School Uniform: After Ten Years (Seifuku shō jo tachi no sentaku, After 10 Years) (2006) and Sharon Kinsella’s Schoolgirls, Money and Rebellion in Japan (2014). In the 1990s, the mass media started to report widely that female high-school students were involved in prostitution or other forms of sex business with middle-aged men as their clients, but these forms of sex business in fact emerged earlier, in the 1980s. -

The Aesthetics of Takarazuka: a Case Study on Erizabēto – Ai to Shi No Rondo

The aesthetics of Takarazuka: a case study on Erizabēto – ai to shi no rondo A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Japanese Department of Japanese University of Canterbury By Daniela Florentina Mageanu 2015 1 Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1 ............................................................................................................................ 1.1 Takarazuka brief background .................................................................................. 8 1.2 Elisabeth – an introduction ..................................................................................... 9 1.3 Methodology .......................................................................................................... 11 1.4 Literature review ................................................................................................... 14 Chapter 2 ............................................................................................................................ 2.1 Early beginnings of the Takarazuka Revue ........................................................... 29 2.2 Takarazuka – war -

Char's Counterattack © 1998, 2002 Sotsu Agency • Sunrise

TT HH EE AA NN II MM EE && MM AA NN GG AA MM AA GG AA ZZ II NN EE $$ 44 .. 99 55 UU SS // CC AA NN PROTOCULTURE PROTOCULTUREAA DD DD II CC TT SS MAGAZINE www.protoculture-mag.com 7373 •• cosmocosmo wwarriorarrior zerozero •• ccowboyowboy bebopbebop thethe moviemovie •• jojojosjos bizarrebizarre Sample file adventureadventure •• natsunatsu hehe nono totobirabira •• projectproject armsarms •• sakurasakura warswars •• scryedscryed •• slayersslayers premiumpremium •• NEWSNEWS && REVIEWSREVIEWS CHAR’S COUNTERATTACK CHAR’S COUNTERATTACK C o v e r 2 o f 2 Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PROTOCULTURE ✾ PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................... 4 STAFF NEWS ANIME & MANGA NEWS: Japan / North America ............................................................... 5, 10 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager ANIME RELEASES (VHS / DVD) & PRODUCTS (Live-Action, Soundtracks, etc.) .............................. 6 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator MANGA RELEASES / MANGA SELECTION / MANGA NEWS .......................................................... 7 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor JAPANESE DVD (R2) RELEASES .............................................................................................. 9 NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 11 Contributing Editors Aaron K. Dawe, Asaka Dawe, Keith Dawe Kevin Lillard, Gerry