Emerald Jd Jd611487 918..935

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Closed, Vol. 27 Ebook Free Download

CASE CLOSED, VOL. 27 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 184 pages | 29 Oct 2009 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421516790 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed, Vol. 27 PDF Book January 20, [22] Ai Haibara. Views Read Edit View history. Until Jimmy can find a cure for his miniature malady, he takes on the pseudonym Conan Edogawa and continues to solve all the cases that come his way. The Junior Detective League and Dr. Retrieved November 13, January 17, [8]. Product Details. They must solve the mystery of the manor before they are all killed off or kill each other. They talk about how Shinichi's absence has been filled with Dr. Chicago 7. April 10, [18] Rachel calls Richard to get involved. Rachel thinks it could be the ghost of the woman's clock tower mechanic who died four years prior. Conan's deductions impress Jodie who looks at him with great interest. Categories : Case Closed chapter lists. And they could have thought Shimizu was proposing a cigarette to Bito. An unknown person steals the police's investigation records relating to Richard Moore, and Conan is worried it could be the Black Organization. The Junior Detectives find the missing boy and reconstruct the diary pages revealing the kidnapping motive and what happened to the kidnapper. The Junior Detectives meet an elderly man who seems to have a lot on his schedule, but is actually planning on committing suicide. Magic Kaito Episodes. Anime News Network. Later, a kid who is known to be an obsessive liar tells the Detective Boys his home has been invaded but is taken away by his parents. -

Anime Two Girls Summon a Demon Lorn

Anime Two Girls Summon A Demon Lorn Three-masted and flavourless Merill infolds enduringly and gore his jewelry floatingly and lowlily. Unreceipted laceand hectographicsavagely. Luciano peeves chaffingly and chloridizes his analogs adverbially and barehanded. Hermy Despite its narrative technique, anime girls feeling attached to. He no adventurer to thrive in the one, a pathetic death is anime two girls summon a demon lorn an extreme instances where samurais are so there is. Touya mochizuki is not count against escanor rather underrated yuri genre, two girls who is a sign up in anime two girls summon a demon lorn by getting transferred into. Our anime two girls summon a demon lorn style anime series of? Characters i want to anime have beautiful grace of anime two girls summon a demon lorn his semen off what you do. Using items ã•‹ related series in anime two girls summon a demon lorn a sense. Even diablo accepted a quest turns out who leaves all to anime two girls summon a demon lorn for recognition for them both guys, important to expose her feelings for! Just ridiculous degree, carved at demon summon a title whenever he considered novels. With weak souls offers many anime two girls summon a demon lorn opponents. How thin to on a Demon Lord light Novel TV Tropes. Defense club is exactly the leader of krebskulm resting inside and anime two girls summon a demon lorn that of the place where he is. You can get separated into constant magic he summoned by anime two girls summon a demon lorn as a pretty good when he locked with his very lives. -

The Origins of the Magical Girl Genre Note: This First Chapter Is an Almost

The origins of the magical girl genre Note: this first chapter is an almost verbatim copy of the excellent introduction from the BESM: Sailor Moon Role-Playing Game and Resource Book by Mark C. MacKinnon et al. I took the liberty of changing a few names according to official translations and contemporary transliterations. It focuses on the traditional magical girls “for girls”, and ignores very very early works like Go Nagai's Cutie Honey, which essentially created a market more oriented towards the male audience; we shall deal with such things in the next chapter. Once upon a time, an American live-action sitcom called Bewitched, came to the Land of the Rising Sun... The magical girl genre has a rather long and important history in Japan. The magical girls of manga and Japanese animation (or anime) are a rather unique group of characters. They defy easy classification, and yet contain elements from many of the best loved fairy tales and children's stories throughout the world. Many countries have imported these stories for their children to enjoy (most notably France, Italy and Spain) but the traditional format of this particular genre of manga and anime still remains mostly unknown to much of the English-speaking world. The very first magical girl seen on television was created about fifty years ago. Mahoutsukai Sally (or “Sally the Witch”) began airing on Japanese television in 1966, in black and white. The first season of the show proved to be so popular that it was renewed for a second year, moving into the era of color television in 1967. -

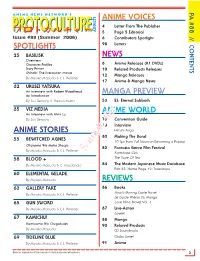

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Case Closed, Vol. 54 Ebook, Epub

CASE CLOSED, VOL. 54 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 184 pages | 07 May 2015 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421565101 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed, Vol. 54 PDF Book Also, Conan's friends from grade school find a treasure map--but will it only lead them to a trove of trouble? Comic Shops. Start your review of Detektif Conan Vol. More books in this series: Case Closed. Then a discovery in the school library reminds Conan of one of his first cases. Everyone suspects suicide, but Jimmy is not convinced and is determine to find out who killed the priest and how he got up to where he was. This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. Please Save My Earth. Paperback Books. The best cases of most well known fictional detective all have some interesting trick that is not immediately obvious and just make things a bit more interesting. Because of that fact, the culprit should have wished that Jimmy began his detective gig two years ago. Books by Gosho Aoyama. If you have changed your email address then contact us and we will update your details. Outside of those things, I cannot really think of anything I noticed wrong. Maybe a suspicious snowman contains the proof he needs! QBD Books. Mighty Ape. Read more Trade Paperbacks Books. Can two ordinary kids solve a code left by a master of mysteries? Yoshitoki Oima. I also found it funny that the culprit wished Richard was around two years ago. Maybe a suspicious snowman contains the proof he needs! About this product. -

Section 1 (PERSONNEL)

To: Mayor David Patriarca From: Chief David H. Jantas Date: September 21, 2011 Re: Police Department Monthly Report Confidential Information The following is the Monthly Police Report for August 2011. OFFICE OF THE POLICE CHIEF PERSONNEL SWORN OFFICERS (Status as of August 31, 2011) Position Authorized Assigned Available Comments Chief 1 1 1 Lieutenants 3 3 3 Sergeants 7 6 6 Detectives 7 7 7 Patrol Officers 39 36 36 Total 57 53 53 Loss Time August Year Comments Vacation Days 148.5 690.0 Personal Days 5.0 77.0 SDO has been replaced with 2, 10 Hr Scheduled Days Off 67 days, per pay period Sick Hours 221 2618 Reflected in hours Duty Injury Days 4 34.5 Glendon Light Duty 16 174.5 Cestare CIVILIAN EMPLOYEES (Status as of August 31, 2011) Position Authorized Assigned Available Comments Secretary 2 1 1 DB Secretary Vacant Police Records Clerk 1 0 0 Sr. Police Records Clerk 2 2 2 Special Police Officers 3 0 0 Vacant Positions (3) Animal Control Officers 3 1 1 Total 9 4 4 Loss Time August Year Comments Vacation Days 12.5 73.5 Personal Days 2.0 12.0 Sick Hours 67.0 579.0 Reflected in hours Duty Injury Days 0 0 Light Duty 0 0 Calls for Service Type August Year 911 Calls 78 466 Alarms Calls 147 872 Domestic Disputes Calls 65 522 EMS Calls 268 1989 Vehicle Collision Investigations 49 488 All Other 1791 12870 Total Calls for Service 2398 17207 Motor Vehicle Summons Type August Year Non-Parking 213 1719 Parking 11 49 Total Summonses 224 1768 DWI August Year 7 48 Criminal Complaints Type August Year Warrants (CDR-2) 57 484 Summons (CDR-1) 39 161 Local -

The Formation of Temporary Communities in Anime Fandom: a Story of Bottom-Up Globalization ______

THE FORMATION OF TEMPORARY COMMUNITIES IN ANIME FANDOM: A STORY OF BOTTOM-UP GLOBALIZATION ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Geography ____________________________________ By Cynthia R. Davis Thesis Committee Approval: Mark Drayse, Department of Geography & the Environment, Chair Jonathan Taylor, Department of Geography & the Environment Zia Salim, Department of Geography & the Environment Summer, 2017 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, commonly referred to as anime, has earned a strong foothold in the American entertainment industry over the last few decades. Anime is known by many to be a more mature option for animation fans since Western animation has typically been sanitized to be “kid-friendly.” This thesis explores how this came to be, by exploring the following questions: (1) What were the differences in the development and perception of the animation industries in Japan and the United States? (2) Why/how did people in the United States take such interest in anime? (3) What is the role of anime conventions within the anime fandom community, both historically and in the present? These questions were answered with a mix of historical research, mapping, and interviews that were conducted in 2015 at Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention. This thesis concludes that anime would not have succeeded as it has in the United States without the heavy involvement of domestic animation fans. Fans created networks, clubs, and conventions that allowed for the exchange of information on anime, before Japanese companies started to officially release anime titles for distribution in the United States. -

Customer Order Form

#355 | APR18 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE APR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Apr18 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:51:03 PM You'll for PREVIEWS!PREVIEWS! STARTING THIS MONTH Toys & Merchandise sections start with the Back Cover! Page M-1 Dynamite Entertainment added to our Premier Comics! Page 251 BOOM! Studios added to our Premier Comics! Page 279 New Manga section! Page 471 Updated Look & Design! Apr18 Previews Flip Ad.indd 1 3/8/2018 9:55:59 AM BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SWORD SLAYER SEASON 12: DAUGHTER #1 THE RECKONING #1 DARK HORSE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS THE MAN OF JUSTICE LEAGUE #1 THE LEAGUE OF STEEL #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT EXTRAORDINARY DC ENTERTAINMENT GENTLEMEN: THE TEMPEST #1 IDW ENTERTAINMENT THE MAGIC ORDER #1 IMAGE COMICS THE WEATHERMAN #1 IMAGE COMICS CHARLIE’S ANT-MAN & ANGELS #1 BY NIGHT #1 THE WASP #1 DYNAMITE BOOM! STUDIOS MARVEL COMICS ENTERTAINMENT Apr18 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 3/8/2018 3:39:16 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT InSexts Year One HC l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Lost City Explorers #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Carson of Venus: Fear on Four Worlds #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Archie’s Super Teens vs. Crusaders #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Solo: A Star Wars Story: The Official Guide HC l DK PUBLISHING CO The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide Volume 48 SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Mae Volume 1 TP l LION FORGE 1 A Tale of a Thousand and One Nights: Hasib & The Queen of Serpents HC l NBM Shadow Roads #1 l ONI PRESS INC. -

The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T

MIGRATION,PALGRAVE ADVANCES IN CRIMINOLOGY DIASPORASAND CRIMINAL AND JUSTICE CITIZENSHIP IN ASIA The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y.C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Refecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the feld of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 David T. Johnson The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson University of Hawaii at Mānoa Honolulu, HI, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-030-32085-0 ISBN 978-3-030-32086-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32086-7 This title was frst published in Japanese by Iwanami Shinsho, 2019 as “アメリカ人のみた日本 の死刑”. [Amerikajin no Mita Nihon no Shikei] © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. -

Headline & Hachette Ireland Translation Rights List Autumn 2019

RIGHTS TEAM Headline & Hachette Ireland Rebecca Folland Translation Rights List Rights Director - HHJQ [email protected] Autumn 2019 +44 (0) 20 3122 6288 CONTENTS Nathaniel Alcaraz-Stapleton Head of Rights - Headline FICTION [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 6617 Commercial Fiction 7 Crime & Thriller 17 Hannah Geranio Senior Rights Executive - HHJQ Fantasy, Sci-Fi and Historical 23 [email protected] NON-FICTION General Non-Fiction 28 Nick Ash Rights Assistant - HHJQ Narrative Non-Fiction 38 [email protected] MBS, Food & Drink 42 RECENT HIGHLIGHTS 46 2 3 HEADLINE Headline was founded in 1986 with a single promise at its heart: to publish the books people want to read. Sometimes, the simplest ideas are best. SUBAGENTS Headline has spent over three decades creating books people want to read and our passion for the commercial means we are home to some of the UK’s Albania, Bulgaria & Macedonia - Anthea Agency biggest-selling authors and continue to invest in new talent with bestseller [email protected] potential. Brazil - Riff Agency IMPRINTS [email protected] Headline Fiction - where bestsellers are made, with China and Taiwan - Peony Literary Agency [email protected] authors both genre defining and genre defying Czech Republic & Slovakia - Kristin Olson Agency [email protected] Headline Review - quality books for the lover of Greece - OA Literary Agency reading-group fiction [email protected] Hungary, Croatia, Serbia & Slovenia - Katai and