Introduction: Girls' Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cobra the Animation Review

Cobra the animation review [Review] Cobra: The Animation. by Gerald Rathkolb October 12, SHARE. Sometimes, it's refreshing to find something that has little concern with following. May 27, Title: Cobra the Animation Genre: Action/Adventure Company: Magic Bus Format: 12 episodes Dates: 2 Jan to 27 Mar Synopsis: Cobra. Space Adventure Cobra is a hangover from the 80's. it isn't reproduced in this review simply because the number of zeros would look silly. Get ready to blast off, rip-off, and face-off as the action explodes in COBRA THE ANIMATION! The Review: Audio: The audio presentation for. Cobra The Animation – Blu-ray Review. written by Alex Harrison December 5, Sometimes you get a show that is fun and captures people's imagination. visits a Virtual Reality parlor to live out his vague male fantasies, but the experience instead revives memories of being the great space rogue Cobra, scourge of. Here's a quick review. I think that my biggest issue with Cobra is that I unfortunately happened to watch one of the worst Cobra episodes as my. A good reviewer friend of mine, Andrew Shelton at the Anime Meta-Review, has a It's a rating I wish I had when it came to shows like Space Adventure Cobra. Cobra Anime Anthology ?list=PLyldWtGPdps0xDpxmZ95AMcS4wzST1qkq. Not quite a full review, just a quick look at the new Space Adventure Cobra tv series (aka Cobra: the Animation. This isn't always the case though. Sometimes you wonder this same thing about series that are actually good, such as Cobra the Animation. -

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

Global Political Ecology

Global Political Ecology The world is caught in the mesh of a series of environmental crises. So far attempts at resolving the deep basis of these have been superficial and disorganized. Global Political Ecology links the political economy of global capitalism with the political ecology of a series of environmental disasters and failed attempts at environmental policies. This critical volume draws together contributions from 25 leading intellectuals in the field. It begins with an introductory chapter that introduces the readers to political ecology and summarises the book’s main findings. The following seven sections cover topics on the political ecology of war and the disaster state; fuelling capitalism: energy scarcity and abundance; global governance of health, bodies, and genomics; the contradictions of global food; capital’s marginal product: effluents, waste, and garbage; water as a commodity, human right, and power; the functions and dysfunctions of the global green economy; political ecology of the global climate; and carbon emissions. This book contains accounts of the main currents of thought in each area that bring the topics completely up-to-date. The individual chapters contain a theoretical introduction linking in with the main themes of political ecology, as well as empirical information and case material. Global Political Ecology serves as a valuable reference for students interested in political ecology, environmental justice, and geography. Richard Peet holds degrees from the London School of Economics (BSc (Econ)), the University of British Columbia (MA), and the University of California, Berkeley (PhD). He is currently Professor of Geography at Clark University, Worcester, MA. His interests are development, global policy regimes, power, theory and philosophy, political ecology, and the causes of financial crises. -

Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender Kazue Harada Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2015 Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender Kazue Harada Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Harada, Kazue, "Japanese Women's Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender" (2015). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 442. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/442 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of East Asian Languages & Cultures Dissertation Examination Committee: Rebecca Copeland, Chair Nancy Berg Ji-Eun Lee Diane Wei Lewis Marvin Marcus Laura Miller Jamie Newhard Japanese Women’s Science Fiction: Posthuman Bodies and the Representation of Gender by Kazue Harada A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 St. Louis, Missouri © 2015, Kazue Harada -

Western Literature in Japanese Film (1910-1938) Alex Pinar

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

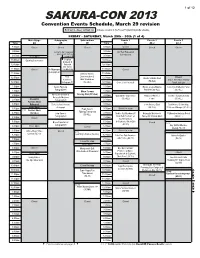

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

Referencia Bibliográfica: Saito, K. (2011). Desire in Subtext: Gender

Referencia bibliográfica: Saito, K. (2011). Desire in Subtext: Gender, Fandom, and Women’s Male-Male Homoerotic Parodies in Contemporary Japan. Mechademia, 6, 171–191. Disponible en https://muse.jhu.edu/article/454422 ISSN: - 'HVLUHLQ6XEWH[W*HQGHU)DQGRPDQG:RPHQ V0DOH0DOH +RPRHURWLF3DURGLHVLQ&RQWHPSRUDU\-DSDQ .XPLNR6DLWR Mechademia, Volume 6, 2011, pp. 171-191 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI0LQQHVRWD3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/mec.2011.0000 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mec/summary/v006/6.saito.html Access provided by University of Sydney Library (13 Nov 2015 18:03 GMT) KumiKo saito Desire in Subtext: Gender, Fandom, and Women’s Male–Male Homoerotic Parodies in Contemporary Japan Manga and anime fan cultures in postwar Japan have expanded rapidly in a manner similar to British and American science fiction fandoms that devel- oped through conventions. From the 1970s to the present, the Comic Market (hereafter Comiket) has been a leading venue for manga and anime fan activi- ties in Japan. Over the three days of the convention, more than thirty-seven thousand groups participate, and their dōjinshi (self-published fan fiction) and character goods generate ¥10 billion in sales.1 Contrary to the common stereo- type of anime/manga cult fans—the so-called otaku—who are males in their twenties and thirties, more than 70 percent of the participants in this fan fic- tion market are reported to be women in their twenties and thirties.2 Dōjinshi have created a locus where female fans vigorously explore identities and desires that are usually not expressed openly in public. The overwhelming majority of women’s fan fiction consists of stories that adapt characters from official me- dia to portray male–male homosexual romance and/or erotica. -

A Thesis Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki, Communal Illusion, and The

A Thesis entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki, Communal Illusion, and the Japanese New Left by Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for requirements for The Master of Arts Degree in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. William D. Hoover ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo (July 2005) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is customary in a note of acknowledgments to make the usual mea culpa concerning the impossibility of enumerating all the people to whom the author has incurred a debt in writing his or her work, but, in my case, this is far truer than I can ever say. This note is, therefore, a necessarily abbreviated one and I ask for a small jubilee, cancellation of all debts, from those that I fail to mention here due to lack of space and invidiously ungrateful forgetfulness. Prof. Peter Linebaugh, sage of the trans-Atlantic commons, who, as peerless mentor and comrade, kept me on the straight and narrow with infinite "grandmotherly kindness" when my temptation was always to break the keisaku and wander off into apostate digressions; conversations with him never failed to recharge the fiery voltage of necessity and desire of historical imagination in my thinking. The generously patient and supportive free rein that Prof. William D. Hoover, the co-chair of my thesis committee, gave me in exploring subjects and interests of my liking at my own preferred pace were nothing short of an ideal that all academic apprentices would find exceedingly enviable; his meticulous comments have time and again mercifully saved me from committing a number of elementary factual and stylistic errors. -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W Inte R 2 0 18 – 19

WINTER 2018–19 BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE 100 YEARS OF COLLECTING JAPANESE ART ARTHUR JAFA MASAKO MIKI HANS HOFMANN FRITZ LANG & GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM INGMAR BERGMAN JIŘÍ TRNKA MIA HANSEN-LØVE JIA ZHANGKE JAMES IVORY JAPANESE FILM CLASSICS DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT IN FOCUS: WRITING FOR CINEMA 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 CALENDAR DEC 9/SUN 21/FRI JAN 2:00 A Midsummer Night’s Dream 4:00 The Price of Everything P. 15 Introduction by Jan Pinkava 7:00 Fanny and Alexander BERGMAN P. 15 1/SAT TRNKA P. 12 3/THU 7:00 Full: Home Again—Tapestry 1:00 Making a Performance 1:15 Exhibition Highlights Tour P. 6 4:30 The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari P. 5 WORKSHOP P. 6 Reimagined Judith Rosenberg on piano 4–7 Five Tables of the Sea P. 4 5:30 The Good Soldier Švejk TRNKA P. 12 LANG & EXPRESSIONISM P. 16 22/SAT Free First Thursday: Galleries Free All Day 7:30 Persona BERGMAN P. 14 7:00 The Price of Everything P. 15 6:00 The Firemen’s Ball P. 29 5/SAT 2/SUN 12/WED 8:00 The Apartment P. 19 6:00 Future Landscapes WORKSHOP P. 6 12:30 Scenes from a 6:00 Arthur Jafa & Stephen Best 23/SUN Marriage BERGMAN P. 14 CONVERSATION P. 6 9/WED 2:00 Boom for Real: The Late Teenage 2:00 Guided Tour: Old Masters P. 6 7:00 Ugetsu JAPANESE CLASSICS P. 20 Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat P. 15 12:15 Exhibition Highlights Tour P. -

A Japanese View of “The Other World” Reflected in the Movie “Departures

13. A Japanese view of the Other World reflected in the movie “Okuribito (Departures)” Keiko Tanita Introduction Religion is the field of human activities most closely related to the issue of death. Japan is considered to be a Buddhist country where 96 million people support Buddhism with more than 75 thousands temples and 300 thousands Buddha images, according to the Cultural Affaires Agency in 2009. Even those who have no particular faith at home would say they are Buddhist when asked during their stay in other countries where religion is an important issue. Certainly, a great part of our cultural tradition is that of Buddhism, which was introduced into Japan in mid-6th century. Since then, Buddhism spread first among the aristocrats, then down to the common people in 13th century, and in the process it developed a synthesis of the traditions of the native Shintoism. Shintoism is a religion of the ancient nature and ancestor worship, not exactly the same as the present-day Shintoism which was institutionalized in the late 19th century in the course of modernization of Japan. Presently, we have many Buddhist rituals especially related to death and dying; funeral, death anniversaries, equinoctial services, the Bon Festival similar to Christian All Souls Day, etc. and most of them are originally of Japanese origin. Needless to say, Japanese Buddhism is not same as that first born in India, since it is natural for all religions to be influenced by the cultures specific to the countries/regions where they develop. Japanese Buddhism, which came from India through the Northern route of Tibet and China developed into what is called Mahayana Buddhism which is quite different from the conservative Theravada traditions found in Thai, Burmese, and Sri Lankan Buddhism, which spread through the Southern route.