PDF (Volume I)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaitoskirjascientific MASCULINITY and NATIONAL IMAGES IN

Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki, Finland SCIENTIFIC MASCULINITY AND NATIONAL IMAGES IN JAPANESE SPECULATIVE CINEMA Leena Eerolainen DOCTORAL DISSERTATION To be presented for public discussion with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki, in Room 230, Aurora Building, on the 20th of August, 2020 at 14 o’clock. Helsinki 2020 Supervisors Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Bart Gaens, University of Helsinki, Finland Pre-examiners Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Rikke Schubart, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark Opponent Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Custos Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Copyright © 2020 Leena Eerolainen ISBN 978-951-51-6273-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-6274-8 (PDF) Helsinki: Unigrafia, 2020 The Faculty of Arts uses the Urkund system (plagiarism recognition) to examine all doctoral dissertations. ABSTRACT Science and technology have been paramount features of any modernized nation. In Japan they played an important role in the modernization and militarization of the nation, as well as its democratization and subsequent economic growth. Science and technology highlight the promises of a better tomorrow and future utopia, but their application can also present ethical issues. In fiction, they have historically played a significant role. Fictions of science continue to exert power via important multimedia platforms for considerations of the role of science and technology in our world. And, because of their importance for the development, ideologies and policies of any nation, these considerations can be correlated with the deliberation of the role of a nation in the world, including its internal and external images and imaginings. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi No Kumi (Confraria De Misericórdia)

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi no Kumi (Confraria de Misericórdia) Takashi GONOI Professor Emeritus, University of Tokyo Introduction During the 80-year period starting when the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier and his party arrived in Kagoshima in August of 1549 and propagated their Christian teachings until the early 1630s, it is estimated that a total of 760,000 Japanese converted to Chris- tianity. Followers of Christianity were called “kirishitan” in Japanese from the Portu- guese christão. As of January 1614, when the Tokugawa shogunate enacted its prohibi- tion of the religion, kirishitan are estimated to have been 370,000. This corresponds to 2.2% of the estimated population of 17 million of the time (the number of Christians in Japan today is estimated at around 1.1 million with Roman Catholics and Protestants combined, amounting to 0.9% of total population of 127 million). In November 1614, 99 missionaries were expelled from Japan. This was about two-thirds of the total number in the country. The 45 missionaries who stayed behind in hiding engaged in religious in- struction of the remaining kirishitan. The small number of missionaries was assisted by brotherhoods and sodalities, which acted in the missionaries’ place to provide care and guidance to the various kirishitan communities in different parts of Japan. During the two and a half centuries of harsh prohibition of Christianity, the confraria (“brother- hood”, translated as “kumi” in Japanese) played a major role in maintaining the faith of the hidden kirishitan. An overview of the state of the kirishitan faith in premodern Japan will be given in terms of the process of formation of that faith, its actual condition, and the activities of the confraria. -

Modelo Para Trabalhos Acadêmicos

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS ORIENTAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LÍNGUA, LITERATURA E CULTURA JAPONESA MARIA IVETTE JOB O tempo dos fantasmas de As 53 Estações da Yōkaidō: Mizuki Shigeru e Aby Warburg versão corrigida Vol. I São Paulo 2021 MARIA IVETTE JOB O tempo dos fantasmas de As 53 Estações da Yōkaidō: Mizuki Shigeru e Aby Warburg versão corrigida Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Filosofia do Departamento de Filosofia da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, da Universidade de São Paulo, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Letras. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Michiko Okano Ishiki São Paulo 2021 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo Job, Maria Ivette J62t O tempo dos fantasmas de As 53 Estações da Yôkaidô: Mizuki Shigeru e Aby Warburg / Maria Ivette Job; orientadora Michiko Okano Ishiki - São Paulo, 2021. 178 f. Dissertação (Mestrado)- Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Letras Orientais. Área de concentração: Língua, Literatura e Cultura Japonesa. 1. Cultura Oriental - Japão. 2. Iconologia. 3. Mizuki, Shigeru, 1922-2015.. 4. Warburg, Aby M., 1866-1929.. I. Ishiki, Michiko Okano, orient. II. Título. UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE F FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS ENTREGA DO EXEMPLAR CORRIGIDO DA DISSERTAÇÃO/TESE Termo de Ciência e Concordância do (a) orientador (a) Nome do (a) aluno (a): Maria Ivette Job Data da defesa: 10/06/2021 Nome do Prof. -

Shaping Darkness in Hyakki Yagyō Emaki

Asian Studies III (XIX), 1 (2015), pp.9–27 Shaping Darkness in hyakki yagyō emaki Raluca NICOLAE* Abstract In Japanese culture, the yōkai, the numinous creatures inhabiting the other world and, sometimes, the boundary between our world and the other, are obvious manifestations of the feeling of fear, “translated” into text and image. Among the numerous emaki in which the yōkai appear, there is a specific type, called hyakki yagyō (the night parade of one hundred demons), where all sorts and sizes of monsters flock together to enjoy themselves at night, but, in the end, are scattered away by the first beams of light or by the mysterious darani no hi, the fire produced by a powerful magical invocation, used in the Buddhist sect Shingon. The nexus of this emakimono is their great number, hyakki, (one hundred demons being a generic term which encompasses a large variety of yōkai and oni) as well as the night––the very time when darkness becomes flesh and blood and starts marching on the streets. Keywords: yōkai, night, parade, painted scrolls, fear Izvleček Yōkai (prikazni, demoni) so v japonski kulturi nadnaravna bitja, ki naseljuje drug svet in včasih tudi mejo med našim in drugim svetom ter so očitno manifestacija občutka strahu “prevedena” v besedila in podobe. Med številnimi slikami na zvitkih (emaki), kjer se prikazni pojavljajo, obstaja poseben tip, ki se imenuje hyakki yagyō (nočna parade stotih demonov), kjer se zberejo pošasti različne vrste in velikosti, da bi uživali v noči, vendar jih na koncu preženejo prvi žarki svetlobe ali skrivnosten darani no hi, ogenj, ki se pojavi z močnim magičnim zaklinjanje in se uporablja pri budistični sekti Shingon. -

Matthew P. Funaiole Phd Thesis

HISTORY AND HIERARCHY THE FOREIGN POLICY EVOLUTION OF MODERN JAPAN Matthew P. Funaiole A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2014 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/5843 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence History and Hierarchy The Foreign Policy Evolution of Modern Japan This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Saint Andrews by Matthew P. Funaiole 27 October 2014 Word Count: 79,419 iii Abstract This thesis examines the foreign policy evolution of Japan from the time of its modernization during the mid-nineteenth century though the present. It is argued that infringements upon Japanese sovereignty and geopolitical vulnerabilities have conditioned Japanese leaders towards power seeking policy obJectives. The core variables of statehood, namely power and sovereignty, and the perception of state elites are traced over this broad time period to provide a historical foundation for framing contemporary analyses of Japanese foreign policy. To facilitate this research, a unique framework that accounts for both the foreign policy preferences of Japanese leaders and the external constraints of the international system is developed. Neoclassical realist understandings of self-help and relative power distributions form the basis of the presented analysis, while constructivism offers crucial insights into ideational factors that influence state elites. -

Circus Scam 1.9 0.5 UY Milford, Alison (Ls) Circu

Author Title AR Book AR Interest Joyce, Melanie (Ls) Billy's Boy 1.6 0.5 MY Milford, Alison (Ls) Circus Scam 1.9 0.5 UY Milford, Alison (Ls) Circus Scam 1.9 0.5 UY Milford, Alison (Ls) Circus Scam 1.9 0.5 UY Pearson, Danny (Ls) Escape From The City 1.9 0.5 MY Pearson, Danny (Ls) Escape From The City 1.9 0.5 MY Pearson, Danny (Ls) Football Smash 1.9 0.5 MY Pearson, Danny (Ls) Football Smash 1.9 0.5 MY Pearson, Danny (Ls) Football Smash 1.9 0.5 MY Powell, Jillian (Ls) Cage Boy: Level 5 1.9 0.5 MY Gray, Kes Oi Goat!: World Book Day 2018 2 0.5 LY Hurn, Roger (Ls) Too Hot: Level 3 2 0.5 MY Thomas, Valerie Winnie Flies Again 2 0.5 LY Thomas, Valerie Winnie Flies Again 2 0.5 LY Adams, Spike T. (Ls) Evil Ink 2.1 0.5 UY Adams, Spike T. (Ls) Snap Kick 2.1 0.5 UY Clayton, David Hell-Ride Tonight! 2.1 0.5 MY Cullimore, Stan (Ls) Bubble Attack 2.1 0.5 UY Cullimore, Stan (Ls) Bubble Attack 2.1 0.5 UY Cullimore, Stan (Ls) Robert And The Werewolf 2.1 0.5 UY Cullimore, Stan (Ls) Robert And The Werewolf 2.1 0.5 UY Higson, Charlie Silverfin: The Graphic Novel 2.1 1 MY Lee, Janelle (Ls) Badu Boys Rule! 2.1 0.5 MY Orme, David Boffin Boy And The Emperor's Tomb 2.1 0.5 MY Powell, Jillian (Ls) Chip Boy 2.1 0.5 UY Tompsett, C.L. -

2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan

Yoko Tomiyasu 2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan 1 CONTENTS Biographical information .............................................................3 Statement ................................................................................4 Translation.............................................................................. 11 Bibliography and Awards .......................................................... 18 Five Important Titles with English text Mayu to Oni (Mayu & Ogree) ...................................................... 28 Bon maneki (Invitation to the Summer Festival of Bon) ......................... 46 Chiisana Suzuna hime (Suzuna the Little Mountain Godness) ................ 67 Nanoko sensei ga yatte kita (Nanako the Magical Teacher) ................. 74 Mujina tanteiktoku (The Mujina Ditective Agency) ........................... 100 2 © Yoko Tomiyasu © Kodansha Yoko Tomiyasu Born in Tokyo in 1959, Tomiyasu grew up listening to many stories filled with monsters and wonders, told by her grandmother and great aunts, who were all lovers of storytelling and mischief. At university she stud- ied the literature of the Heian period (the ancient Japanese era lasting from the 8th to 12 centuries AD). She was deeply attracted to stories of ghosts and ogres in Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), and fell more and more into the world of traditional folklore. She currently lives in Osaka with her husband and two sons. There was a long era of writing stories that I wanted to read for myself. The origin of my creativity is the desire to write about a wonderous world that children can walk into from their everyday life. I want to write about the strange and mysterious world that I have loved since I was a child. 3 STATEMENT Recommendation of Yoko Tomiyasu for the Hans Christian Andersen Award Akira Nogami editor/critic Yoko Tomiyasu is one of Japan’s most popular Pond).” One hundred copies were printed. It authors and has published more than 120 was 1977 and Tomiyasu was 18. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

Myths & Legends of Japan

Myths & Legends Of Japan By F. Hadland Davis Myths & Legends of Japan CHAPTER I: THE PERIOD OF THE GODS In the Beginning We are told that in the very beginning "Heaven and Earth were not yet separated, and the In and Yo not yet divided." This reminds us of other cosmogony stories. The In and Yo, corresponding to the Chinese Yang and Yin, were the male and female principles. It was more convenient for the old Japanese writers to imagine the coming into being of creation in terms not very remote from their own manner of birth. In Polynesian mythology we find pretty much the same conception, where Rangi and Papa represented Heaven and Earth, and further parallels may be found in Egyptian and other cosmogony stories. In nearly all we find the male and female principles taking a prominent, and after all very rational, place. We are told in theNihongi that these male and female principles "formed a chaotic mass like an egg which was of obscurely defined limits and contained germs." Eventually this egg was quickened into life, and the purer and clearer part was drawn out and formed Heaven, while the heavier element settled down and became Earth, which was "compared to the floating of a fish sporting on the surface of the water." A mysterious form resembling a reed-shoot suddenly appeared between Heaven and Earth, and as suddenly became transformed into a God called Kuni-toko- tachi, ("Land-eternal-stand-of-august-thing"). We may pass over the other divine births until we come to the important deities known as Izanagi and Izanami ("Male-who-invites" and "Female-who-invites"). -

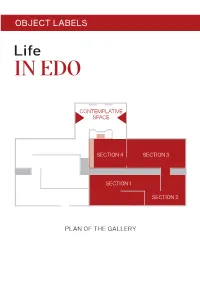

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

Tobacco Accessories

Tobacco Accessories Japanese men in the Edo period (1615–1868) wore various accessories suspended from their kimono waist sashes, including tobacco implements. Tobacco was smoked with long pipes (kiseru), which were stored in pipe cases of various designs. The objects shown here include a tobacco pouch and pipe case set as well as individual pipe cases and lacquered tobacco containers (inro). A Japanese woodblock print depicting tobacco 長谷川一虎作 邯鄲夢に牡丹唐草文革 煙管 銘「千賀政光」 籐製網代編無双筒 昭玉作 猩々網代編籐地象牙珊瑚無双筒 accessories can be seen on the 提げ煙草入れ Pipe (kiseru) Pipe case (musozutsu type) Pipe case (musozutsu type) with the Matched tobacco set with the Approx. 1850–1900 Approx. 1800–1900 drunken sea sprite Shojo dancing other side of this placard. design of Lu Sheng’s dream and Signed Chiga Masamitsu Edo (1615–1868) or Meiji period with sake cup peony scrolls Edo (1615–1868) or Meiji period (1868–1912) Approx. 1800–1900 All objects were made in Approx. 1850–1900 (1868–1912) Rattan and copper alloy By Shogyoku (Japanese, active 19th Japan and are from The Avery By Hasegawa Ikko (Japanese, active Copper alloy with gold and silver B70M25 century) Brundage Collection. 19th century) B70M18 A musozutsu is a type of pipe case with Edo (1615–1868) or Meiji period Leather with lacquer, ivory, and bronze This lavish tobacco set comprises two cylindrical parts, one of which fits (1868–1912) with gilding a tobacco pouch, pipe case, pipe, perfectly into the other. While such cases Rattan with coral, ivory, and lacquer B70M18 netsuke toggle, and a connecting were made from a variety of materials, B70M23 chain made from segments of carved this case was fashioned from finely ivory openwork.