Chinese Historical Records and Sino-Roman Relations: a Critical Approach to Understand Problems on the Chinese Reception of the Roman Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern and Western Look at the History of the Silk Road

Journal of Critical Reviews ISSN- 2394-5125 Vol 7, Issue 9, 2020 EASTERN AND WESTERN LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF THE SILK ROAD Kobzeva Olga1, Siddikov Ravshan2, Doroshenko Tatyana3, Atadjanova Sayora4, Ktaybekov Salamat5 1Professor, Doctor of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 2Docent, Candidate of historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 3Docent, Candidate of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 4Docent, Candidate of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 5Lecturer at the History faculty, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] Received: 17.03.2020 Revised: 02.04.2020 Accepted: 11.05.2020 Abstract This article discusses the eastern and western views of the Great Silk Road as well as the works of scientists who studied the Great Silk Road. The main direction goes to the historiography of the Great Silk Road of 19-21 centuries. Keywords: Great Silk Road, Silk, East, West, China, Historiography, Zhang Qian, Sogdians, Trade and etc. © 2020 by Advance Scientific Research. This is an open-access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.09.17 INTRODUCTION another temple in Suzhou, sacrifices are offered so-called to the The historiography of the Great Silk Road has thousands of “Yellow Emperor”, who according to a legend, with the help of 12 articles, monographs, essays, and other kinds of investigations. -

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society Heather Langford Theses submitted for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Centre of Asian Studies University of Adelaide May 2009 ii Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the research requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Centre of Asian Studies School of Humanities and Social Sciences Adelaide University 2009 iii Table of Contents 1. Introduction.........................................................................................1 1.1. Literature Review..............................................................................13 1.2. Chapter summary ..............................................................................17 1.3. Conclusion ........................................................................................19 2. Background .......................................................................................20 2.1. Pre Han History.................................................................................20 2.2. Qin Dynasty ......................................................................................24 2.3. The Han Dynasty...............................................................................25 2.3.1. Trade with the West............................................................................. 30 2.4. Conclusion ........................................................................................32 3. Textiles and Technology....................................................................33 -

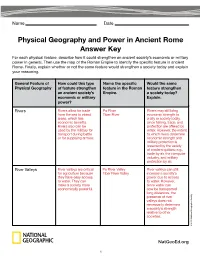

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 The Silk Roads An ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 International Council of Monuments and Sites 11 rue du Séminaire de Conflans 94220 Charenton-le-Pont FRANCE ISBN 978-2-918086-12-3 © ICOMOS All rights reserved Contents STATES PARTIES COVERED BY THIS STUDY ......................................................................... X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... XI 1 CONTEXT FOR THIS THEMATIC STUDY ........................................................................ 1 1.1 The purpose of the study ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background to this study ......................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Global Strategy ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Cultural routes ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2.3 Serial transnational World Heritage nominations of the Silk Roads .................................................. 3 1.2.4 Ittingen expert meeting 2010 ........................................................................................................... 3 2 THE SILK ROADS: BACKGROUND, DEFINITIONS -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Khmer Civilization in Isan Khemita Visudharomn School of Architecture, Assumption University Bangkok, Thailand

AU J.T. 8(4): 178-184 (Apr. 2005) Khmer Civilization in Isan Khemita Visudharomn School of Architecture, Assumption University Bangkok, Thailand Abstract Follow the footsteps of Khmer civilization from Angkor Wat to the center of cultural heritage in northeastern Thailand, Phimai, Phanom Rung and Mueang Tam. This paper is both an introduction and guide to Khmer temples in Isan. The first part begins with historical details tracing the Angkorean from the 8th to 12th century, and introduces a background to the religious traditions of the Khmer, which both inspired and governed the concept and execution of all their art and architecture. The second part is an emphasis on architecture and decorative art, which appear in Khmer temples. In its heyday the main concentration of Khmer temples extended far west to the border and associated with an area of the middle Mekong River in the southern part of northeastern Thailand. Keywords: cultural heritage, Phimai, Phanom Rung, Mueang Tam, the Angkorean, religious traditions, architecture and decorative art 1. Introduction The other sources of information on this period are Chinese accounts and references, in The name “Isan” refers to the these to tributary states such as Funan and northeastern part of Thailand .It covers an area Chenla. of one third of the Kingdom. Isan, is also th th known as the Khorat Plateau. The Phetchabun 2.1 Angkorean (8 - 12 century) Rage separates Isan from the Central Region while the Dongrek Mountains in the south The art and architecture of the Khmer has separate Thailand from Cambodia. The Mun been classified into periods, by French art and Chi Rivers drain the majority of the historians. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

Supplied Through the Parthians) from the 1St Century BC, Even Though the Romans Thought Silk Was Obtained from Trees

Chinese Silk in the Roman Empire Trade with the Roman Empire followed soon, confirmed by the Roman craze for Chinese silk (supplied through the Parthians) from the 1st century BC, even though the Romans thought silk was obtained from trees: The Seres (Chinese), are famous for the woolen substance obtained from their forests; after a soaking in water they comb off the white down of the leaves... So manifold is the labor employed, and so distant is the region of the globe drawn upon, to enable the Roman maiden to flaunt transparent clothing in public. -(Pliny the Elder (23- 79, The Natural History) The Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds: the importation of Chinese silk caused a huge outflow of gold, and silk clothes were considered to be decadent and immoral: I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body. -(Seneca the Younger (c. 3 BCE- 65 CE, Declamations Vol. I) The Roman historian Florus also describes the visit of numerous envoys, included Seres (perhaps the Chinese), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 BCE and 14 CE: Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. -

Opening Essential Questions? Lesson Objectives

Silk Road Curriculum Project 2018-2019 Ingrid Herskind Title of Lesson Plan: Silk Road: Cartography and Trade in Ancient and Modern China Ingrid Herskind, Flintridge Prep School, La Canada, CA Lesson Overview: Students will explore the “Silk Road” trade networks by investigating a route, mapping the best path, and portraying a character who navigated the route. Opening essential questions? How did the Silk Road routes represent an early version of worldwide integration and development? How does China’s modern One Belt, One Road project use similar routes and methodologies as the earlier Silk Road project? How is this modern project different? Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to: Students will also apply skills from the Global Competence Matrix and will: • Investigate the world beyond their immediate environment by identifying an issue, generating a question, and explaining its significance locally, regionally, and globally. • Recognize their own and others’ perspectives by understanding the influences that impact those perspectives. • Communicate their ideas effectively with diverse audiences by realizing how their ideas and delivery can be perceived. • Translate their ideas and findings into appropriate actions to improve conditions and to create opportunities for personal and collaborative action. 1 1 World Savvy, Global Competence Matrix, Council of Chief State School Officers’ EdSteps Project in partnership with the Asia Society Partnership for Global Learning, 2010 1 Silk Road Curriculum Project 2018-2019 Ingrid Herskind Length of Project: This lesson as designed to take place over 2-3 days (periods are either 45 min or 77 min) in 9th Grade World History. Grade Level: High School (gr 9) World History, variation in International Relations 12th grade Historical Context: • China was a key player in the networks that crossed from one continent to another. -

Syriac, Sogdian and Old Uyghur Manuscripts from Bulayïq*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online Syriac, Sogdian and Old Uyghur Manuscripts from Bulayïq Syriac, Sogdian and Old Uyghur Manuscripts from Bulayïq * Erica C.D. Hunter Department for the Study of Religions, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, The German Turfan Expedition conducted 4 campaigns at the Turfan Oasis between 1902 and 1914 bringing 40,000 fragments in 20 scripts and 22 languages back to Berlin. During the 2nd and 3rd seasons (1904 – 1907), a library was unearthed at the monastery site of Shuïpang near Bulayïq yielding ca.1100 fragments written in Syriac script and covering 3 major languages: Syriac, Sogdian and old Uyghur. Several fragments in New Persian and a Middle Persian (Pahlavi) Psalter were also found[1]. Small quantities of Christian texts, in Syriac, Sogdian, Uyghur and Persian, were discovered at other sites in the Turfan oasis (Astana, Qocho, Qurutqa and Toyoq). Regrettably, there are scant remarks about the excavation of the archive by Theodor Bartus at Bulayïq, north of the city of Turfan, a site which von Le Coq had previously visited. Talking about his colleague’s visit, von Le Coq stated in his book Auf Hellas Spuren in Ostturkistan: “er hat ... in dem schauerlich zerstörten Gemäuer eine fabelhafte Ausbeute christlicher Handschriften ausbegraben” (he excavated ... in the extremely ruined walls an amazing Christian manuscript”)[2]. The Syriac - script fragments from Turfan shed invaluable light onto the eastward missionary expansion of the Church of the East whose dioceses extended into Central Asia, China and Mongolia up till the 14th century, not only attesting the nature and expression of worship (liturgy etc) that was conducted, but also revealing how this branch of Eastern Christianity interacted with the local languages and cultures of its diverse congregations. -

Hardships from the Arabian Gulf to China: the Challenges That Faced Foreign Merchants Between the Seventh

57 Dirasat Hardships from the Arabian Gulf to China: The Challenges that Faced Foreign Merchants Between the Seventh Dhul Qa'dah, 1441 - July 2020 and Thirteenth Centuries WAN Lei Hardships from the Arabian Gulf to China: The Challenges that Faced Foreign Merchants Between the Seventh and Thirteenth Centuries WAN Lei © King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, 2020 King Fahd National Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lei, WAN Hardships from the Arabian Gulf to China: The Challenges that Faced Foreign Merchants Between the Seventh and Thirteenth Centuries. / Lei. WAN. - Riyadh, 2020 52 p ; 23 x 16.5 cm ISBN: 978-603-8268-57-5 1- China - Foreign relations I-Title 327.51056 dc 1441/12059 L.D. no. 1441/12059 ISBN: 978-603-8268-57-5 Table of Contents Introduction 6 I. Dangers at Sea 10 II. Troubles from Warlords and Pirates 19 III. Imperial Monopolies, Duty-Levies and Prohibitions 27 IV. Corruption of Officialdom 33 V. Legal Discrimination 39 Conclusion 43 5 6 Dirasat No. 57 Dhul Qa'dah, 1441 - July 2020 Introduction During the Tang (618–907) and Northern Song (960–1127) dynasties, China had solid national strength and a society that was very open to the outside world. By the time of the Southern Song (1127–1279) dynasty, the national economic weight of the country moved to South China; at the same time, the Abbasid Caliphate in the Mideast had grown into a great power, too, whose eastern frontier reached the western regions of China, that is, today’s Xinjiang and its adjacent areas in Central Asia. -

A New Date for the Phnom Da Images and Its Implications for Early Cambodia

A New Date for the Phnom Da Images and Its Implications for Early Cambodia NANCY H. DOWLING SCHOLARS FAMILIAR WITH SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART HISTORY are well aware of a confusing chronology for early Cambodian sculpture. One reason for this situa tion is obvious. For nearly fifty years, Cambodian art history has been wed to the work of George Coedes. Praised as the dean of Southeast Asian history, he was a member of an elite group of French scholars who worked in Cambodia for decades before World War II. In 1944, he wrote Histoire ancienne des hats hindouses d'Extreme-Orient, in which he established a chronological framework for early Southeast Asian history based on an interplay of Chinese texts and indigenous inscriptions. Most Southeast Asian historians readily admit that "his book remains the basic source for early South East Asian history, and while much recent re search, based upon new inscriptional evidence or re-readings, modifies some of Coedes' specific conclusions, the structure remains his" (Brown 1996: 3). Such a singular dependency on Coedes had a stifling effect on Cambodian art history. When Jean Boisselier, carrying on the work of Philippe Stern and Gilberte de Coral-Remusat, made a comprehensive attempt to set in order Cambodian sculpture, the French art historian fitted the works of art into Coedes' ready made chronology. Unfortunately, this all happened as if it were preferable to adjust Cambodian sculpture to a preconceived notion of history rather than ques tioning the model. In this way, some basic mistakes have been made, and these seriously affect the chronology and interpretation of early Cambodian sculpture.