The University of Chicago on Non-Culminating Accomplishments in Mandarin a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

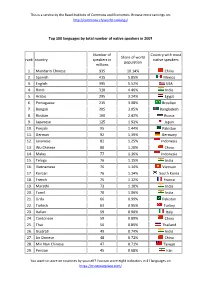

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Women and the Law Reprinted Congressional

WOMEN AND THE LAW REPRINTED FROM THE 2007 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 40–784 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:14 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\40784.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana MICHAEL M. HONDA, California CARL LEVIN, Michigan TOM UDALL, New Mexico DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey MEL MARTINEZ, Florida EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS PAULA DOBRIANSKY, Department of State CHRISTOPHER R. HILL, Department of State HOWARD M. RADZELY, Department of Labor DOUGLAS GROB, Staff Director MURRAY SCOT TANNER, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:14 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\40784.TXT DEIDRE C O N T E N T S Page Status of Women ............................................................................................. -

Cantonese Vs. Mandarin: a Summary

Cantonese vs. Mandarin: A summary JMFT October 21, 2015 This short essay is intended to summarise the similarities and differences between Cantonese and Mandarin. 1 Introduction The large geographical area that is referred to as `China'1 is home to many languages and dialects. Most of these languages are related, and fall under the umbrella term Hanyu (¡£), a term which is usually translated as `Chinese' and spoken of as though it were a unified language. In fact, there are hundreds of dialects and varieties of Chinese, which are not mutually intelligible. With 910 million speakers worldwide2, Mandarin is by far the most common dialect of Chinese. `Mandarin' or `guanhua' originally referred to the language of the mandarins, the government bureaucrats who were based in Beijing. This language was based on the Bejing dialect of Chinese. It was promoted by the Qing dynasty (1644{1912) and later the People's Republic (1949{) as the country's lingua franca, as part of efforts by these governments to establish political unity. Mandarin is now used by most people in China and Taiwan. 3 Mandarin itself consists of many subvarities which are not mutually intelligible. Cantonese (Yuetyu (£) is named after the city Canton, whose name is now transliterated as Guangdong. It is spoken in Hong Kong and Macau (with a combined population of around 8 million), and, owing to these cities' former colonial status, by many overseas Chinese. In the rest of China, Cantonese is relatively rare, but it is still sometimes spoken in Guangzhou. 2 History and etymology It is interesting to note that the Cantonese name for Cantonese, Yuetyu, means `language of the Yuet people'. -

Singapore Mandarin Chinese : Its Variations and Studies

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Singapore Mandarin Chinese : its variations and studies Lin, Jingxia; Khoo, Yong Kang 2018 Lin, J., & Khoo, Y. K. (2018). Singapore Mandarin Chinese : its variations and studies. Chinese Language and Discourse, 9(2), 109‑135. doi:10.1075/cld.18007.lin https://hdl.handle.net/10356/136920 https://doi.org/10.1075/cld.18007.lin © 2018 John Benjamins Publishing Company. All rights reserved. This paper was published in Chinese Language and Discourse and is made available with permission of John Benjamins Publishing Company. Downloaded on 26 Sep 2021 00:28:12 SGT To appear in Chinese Language and Discourse (2018) Singapore Mandarin Chinese: Its Variations and Studies* Jingxia Lin and Yong Kang Khoo Nanyang Technological University Abstract Given the historical and linguistic contexts of Singapore, it is both theoretically and practically significant to study Singapore Mandarin (SM), an important member of Global Chinese. This paper aims to present a relatively comprehensive linguistic picture of SM by overviewing current studies, particularly on the variations that distinguish SM from other Mandarin varieties, and to serve as a reference for future studies on SM. This paper notes that (a) current studies have often provided general descriptions of the variations, but less on individual variations that may lead to more theoretical discussions; (b) the studies on SM are primarily based on the comparison with Mainland China Mandarin; (c) language contact has been taken as the major contributor of the variation in SM, whereas other factors are often neglected; and (d) corpora with SM data are comparatively less developed and the evaluation of data has remained largely in descriptive statistics. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Mandarin Chinese As a Second Language: a Review of Literature Wesley A

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Honors Research Projects College Fall 2015 Mandarin Chinese as a Second Language: A Review of Literature Wesley A. Spencer The University Of Akron, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Spencer, Wesley A., "Mandarin Chinese as a Second Language: A Review of Literature" (2015). Honors Research Projects. 210. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/210 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Running head: MANDARIN CHINESE AS A SECOND LANGUAGE 1 Mandarin Chinese as a Second Language: A Review of Literature Abstract Mandarin Chinese has become increasing prevalent in the modern world. Accordingly, research of Chinese as a second language has developed greatly over the past few decades. This paper reviews research on the difficulties of acquiring a second language in general and research that specifically details the difficulty of acquiring Chinese as a second language. -

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Ruizhong Ding aus Qishan, VR. China Bonn, 2019 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Dr. Manfred Hutter, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kubin, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Betreuer und Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Ralph Kauz, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Veronika Veit, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung:22.07.2019 Acknowledgements Currently, when this dissertation is finished, I look out of the window with joyfulness and I would like to express many words to all of you who helped me. Prof. Wolfgang Kubin accepted me as his Ph.D student and in these years he warmly helped me a lot, not only with my research but also with my life. In every meeting, I am impressed by his personality and erudition deeply. I remember one time in his seminar he pointed out my minor errors in the speech paper frankly and patiently. I am indulged in his beautiful German and brilliant poetry. His translations are full of insightful wisdom. Every time when I meet him, I hope it is a long time. I am so grateful that Prof. Ralph Kauz in the past years gave me unlimited help. In his seminars, his academic methods and sights opened my horizons. Usually, he supported and encouraged me to study more fields of research. -

China's Capacity to Manage Infectious Diseases

China’s Capacity to Manage Infectious Diseases CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & Global Implications CSIS INTERNATIONAL STUDIES A Report of the CSIS Freeman Chair in China Studies 1800 K Street | Washington, DC 20006 PROJECT DIRECTOR Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Charles W. Freeman III E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org PROJECT EDITOR Xiaoqing Lu March 2009 ISBN 978-0-89206-580-6 CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & Ë|xHSKITCy065806zv*:+:!:+:! CSIS INTERNATIONAL STUDIES China’s Capacity to Manage Infectious Diseases Global Implications A Report of the CSIS Freeman Chair in China Studies PROJECT DIRECTOR Charles W. Freeman III PROJECT EDITOR Xiaoqing Lu March 2009 About CSIS In an era of ever-changing global opportunities and challenges, the Center for Strategic and Inter- national Studies (CSIS) provides strategic insights and practical policy solutions to decisionmak- ers. CSIS conducts research and analysis and develops policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke at the height of the Cold War, CSIS was dedicated to the simple but urgent goal of finding ways for America to survive as a nation and prosper as a people. Since 1962, CSIS has grown to become one of the world’s preeminent public policy institutions. Today, CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. More than 220 full-time staff and a large network of affiliated scholars focus their expertise on defense and security; on the world’s regions and the unique challenges inherent to them; and on the issues that know no boundary in an increasingly connected world. -

Chinese Zheng and Identity Politics in Taiwan A

CHINESE ZHENG AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN TAIWAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSIC DECEMBER 2018 By Yi-Chieh Lai Dissertation Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Byong Won Lee R. Anderson Sutton Chet-Yeng Loong Cathryn H. Clayton Acknowledgement The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. First of all, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Frederick Lau, for his professional guidelines and mentoring that helped build up my academic skills. I am also indebted to my committee, Dr. Byong Won Lee, Dr. Anderson Sutton, Dr. Chet- Yeng Loong, and Dr. Cathryn Clayton. Thank you for your patience and providing valuable advice. I am also grateful to Emeritus Professor Barbara Smith and Dr. Fred Blake for their intellectual comments and support of my doctoral studies. I would like to thank all of my interviewees from my fieldwork, in particular my zheng teachers—Prof. Wang Ruei-yu, Prof. Chang Li-chiung, Prof. Chen I-yu, Prof. Rao Ningxin, and Prof. Zhou Wang—and Prof. Sun Wenyan, Prof. Fan Wei-tsu, Prof. Li Meng, and Prof. Rao Shuhang. Thank you for your trust and sharing your insights with me. My doctoral study and fieldwork could not have been completed without financial support from several institutions. I would like to first thank the Studying Abroad Scholarship of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan and the East-West Center Graduate Degree Fellowship funded by Gary Lin. -

The Investigation and Recording of Contemporary Taiwanese Calligraphers the Ink Trend Association and Xu Yong-Jin

The Investigation and Recording of Contemporary Taiwanese Calligraphers The Ink Trend Association and Xu Yong-jin Ching-Hua LIAO Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Professional Doctorate in Design National Institute for Design Research Faculty of Design Swinburne University of Technology March 2008 Ching-Hua LIAO Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Professional Doctorate in Design National Institute for Design Research Faculty of Design Swinburne University of Technology March 2008 Abstract The aim of this thesis is both to highlight the intrinsic value and uniqueness of the traditional Chinese character and to provide an analysis of contemporary Taiwanese calligraphy. This project uses both the thesis and the film documentary to analyse and record the achievement of the calligraphic art of the first contemporary Taiwanese calligraphy group, the Ink Trend Association, and the major Taiwanese calligrapher, Xu Yong-jin. The significance of the recording of the work of the Ink Trend Association and Xu Yong- jin lies not only in their skills in executing Chinese calligraphy, but also in how they broke with tradition and established a contemporary Taiwanese calligraphy. The documentary is one of the methods used to record history. Art documentaries are in a minority in Taiwan, and especially documentaries that explore calligraphy. This project recorded the Ink Trend Association and Xu Yong-jin over a period of five years. It aims to help scholars researching Chinese culture to cherish the beauty of the Chinese character, that they may endeavour to protect it from being sacrificed on the altar of political power, and that more research in this field may be stimulated. -

Chinese (Cantonese) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CHINESE (CANTONESE) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Inc. Penton Overseas | 250 pages | 01 Apr 2000 | PENTON OVERSEAS INC | 9781560156185 | English, Chinese | Carlsbad, CA, United States Chinese (Cantonese) PDF Book From these sources we can see how the question of a speech being a language or a dialect is not merely a linguistic issue, but also involves politics. However after reading the other answers and comments of which I think many are excellent , I felt this was missing from the whole picture:. In some ways this is similar to comparing the Italian and Spanish languages, they both share common roots in Latin but have developed into quite different languages. Chinese Language Stack Exchange is a question and answer site for students, teachers, and linguists wanting to discuss the finer points of the Chinese language. Both Mandarin and Cantonese refer to spoken languages that are members of the Sinitic linguistic family. Here is a banner from Hong Kong that shows some written Cantonese. The formal writing in HK and Taiwan is heavily influenced by Mandarin though. Ask Question. Families with children. Therefore Cantonese should be considered to be an independent language. StumpyJoePete Maybe it is a great argument whether it's a different language or dialect. Viewed 7k times. Here are some of the basic characters we have covered in Mandarin Chinese with the Cantonese equivalent. Improve this question. Quick Form Please complete the quick form below, we will get back to you within 12 hours working day. Chinese, Asian. Although Mandarin and Cantonese share some similarities, they differ in many linguistic aspects including phonology, syntax and semantics. -

On the Status of “Prenuclear” Glides in Mandarin Chinese: Articulatory

Temporal Organization of On-glides across Sinitic languages Feng-fan Hsieh, Guan-sheng Li and Yueh- chin Chang National Tsing Hua University Acknowledgements • We would like to thank Louis Goldstein, Mark Tiede, Jason Shaw, Donald Derrick, Cathi Best, Michael Kenstowicz, Yen-Hwei Lin, Chiu-yu Tseng for assistance, questions, and/or comments. • This work is funded by a Ta-you Wu Memorial Award Grant (103-2410-H-007-036-MY3) from Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Struck in the “medial”... • This work is a cross-linguistic/dialectal study of on-glides (a.k.a. pre-nuclear glides, the medial, etc.) in Sinitic languages. • How is the medial represented phonologically? • The medial (distinct sub-syllabic constituent) • Part of the onset • Part of the rime • Doubly linked/X-bar-based approach • Flat structure (no sub-syllabic constituents) Some previous attempts • See, e.g., Myers (2015) for a recent overview: • Rhyming • Phonotactics (static phonology) • Language game/syllable manipulation experiments • Acceptability judgment tasks • Speech errors • First language acquisition data • Acoustic measurements Puzzling diversity of results in the literature • Those conflicting results support either one of the following interpretations: • Part of the onset: Consonant cluster or secondary articulation • Part of the rime: Onglide or “true” diphthong • Mixed: E.g., /w/ belongs to the onset vs. /j/ belongs to the rime • Flat structure What about articulation? • Regarding syllables such as <suan> ‘sour’ in Mandarin Chinese, • Chao (1934) comments