Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beijing City Day Tour to Forbidden City and Temple of Heaven

www.lilysunchinatours.com Beijing City Day Tour to Forbidden City and Temple of Heaven Basics Tour Code: LCT - BJ - 1D - 04 Duration: 1 Day Attractions: Forbidden City, Temple of Heaven, Summer Palace, Tian’anmen Square Overview: Embark on a journey to four major classic attractions in Beijing in a single day. Take the morning to explore the palatial and extravagant Forbidden City and the biggest city square in the world - Tian’anmen Square. In the afternoon, head for the old royal garden of Summer Palace and Temple of Heaven, the very place where emperors from Ming and Qing Dynasties held grand sacrifice ceremonies to the heaven. Highlights Stroll on the Tian’anmen Square and listen to the stories behind all the monuments, gates, museums and halls. Marvel at the exquisite Forbidden City - the largest palace complex in the world. Enjoy a peaceful time in Summer Palace. Meet a lot of Beijing local people in Temple of Heaven; Satisfy your tongue with a meal full of Beijing delicacies. Itinerary Date Starting Time Destination Day 1 09:00 a.m Forbidden City, Temple of Heaven, Summer Palace, Tian’anmen Square After breakfast, your tour expert and guide will take you to the first destination of the day - Tel: +86 18629295068 1 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] www.lilysunchinatours.com Tian’anmen Square. Seated in the center of Beijing, the square is well-known to be the largest city square in the world. The fact is the Tian’anmen Square is also a witness of numerous historical events and changes. At present, the square has become a place hosting a lot of monuments, museums, halls and the grand celebrations and military parades. -

The Song Elite's Obsession with Death, the Underworld, and Salvation

BIBLID 0254-4466(2002)20:1 pp. 399-440 漢學研究第 20 卷第 1 期(民國 91 年 6 月) Visualizing the Afterlife: The Song Elite’s Obsession with Death, the Underworld, and Salvation Hsien-huei Liao* Abstract This study explores the Song elite’s obsession with the afterlife and its impact on their daily lives. Through examining the ways they perceived the relations between the living and the dead, the fate of their own afterlives, and the functional roles of religious specialists, this study demonstrates that the prevailing ideas about death and the afterlife infiltrated the minds of many of the educated, deeply affecting their daily practices. While affected by contem- porary belief in the underworld and the power of the dead, the Song elite also played an important role in the formation and proliferation of those ideas through their piety and practices. Still, implicit divergences of perceptions and practices between the elite and the populace remained abiding features under- neath their universally shared beliefs. To explore the Song elite’s interactions with popular belief in the underworld, several questions are discussed, such as how and why the folk belief in the afterlife were accepted and incorporated into the elite’s own practices, and how their practices corresponded to, dif- fered from, or reinforced folk beliefs. An examination of the social, cultural, * Hsien-huei Liao is a research associate in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at Harvard University, U.S.A. 399 400 漢學研究第20卷第1期 and political impact on their conceptualization of the afterlife within the broad historical context of the Song is key to understand their beliefs and practices concerning the underworld. -

Elixir, Urine and Hormone: a Socio-Cultural History of Qiushi (Autumn Mineral)*

EASTM 47 (2018): 19-54 Elixir, Urine and Hormone: A Socio-cultural History of Qiushi (Autumn Mineral)* Jing Zhu [ZHU Jing is an Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy, East China Normal University. She received her Ph.D. in history of science at Peking University and in 2015-2016 was a visiting scholar at University of Pennsylvania. She has published three articles about qiushi and two articles about Chinese alchemy. Her paper “Arsenic Prepared by Chinese Alchemist-Pharmacists” was published in Science China Life Sciences. Her work spans historical research on Chinese alchemy, Chinese medicine and public understanding of science. In addition to presenting papers at national and international conferences, she has been invited to present her research among other places at the National Tsinghua University (Taiwan), Brown University, and the University of Pennsylvania. Contact: [email protected]] * * * Abstract: Traditional Chinese medicine has attracted the attention of pharmacologists because some of its remedies have proved useful against cancer and malaria. However, a variety of controversies have arisen regarding the difficulty of identifying and explaining the effectiveness of remedies by biomedical criteria. By exploring the socio-cultural history of qiushi (literally, ‘autumn mineral’), a drug prepared from urine and used frequently throughout Chinese history, I examine how alchemy, popular culture, politics and ritual influenced pre-modern views of the efficacy of the drug, and explore the sharp contrast between views of the drug’s * I especially wish to acknowledge the great help of Professor Nathan Sivin, who has read the complete manuscript and provided me with many critical comments. -

Naturalism in the Philosophies of Dewey and Zhuangzi

Naturalism in the Philosophies of Dewey and Zhuangzi: The Live Creature and the Crooked Tree by Christopher C. Kirby A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: John P. Anton Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Martin Schönfeld Ph.D. Sidney Axinn Ph.D. Alexander Levine Ph.D. Date of Approval: December 12, 2008 Keywords: Pragmatism, Daoism, Metaphysics, Epistemology, Ethics © Copyright 2008 Christopher C. Kirby Dedication For P.J. – “Nature speaks louder than the call from the minaret.” (Inayat Khan, Bowl of Saki) Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................. ii Abstract ..................................................................................................................... iii Preface: West Meets East........................................................................................... 1 Dewey’s Encounter with China ............................................................................. 6 Chapter One: What is Naturalism? .......................................................................... 15 Naturalism and the Organic Point of View .......................................................... 16 Nature and the Language of Experience .............................................................. 22 Naturalistic Strategies in Philosophy .................................................................. -

ILMU MAKRIFAT JAWA SANGKAN PARANING DUMADI Eksplorasi Sufistik Konsep Mengenal Diri Dalam Pustaka Islam Kejawen Kunci Swarga Miftahul Djanati

ILMU MAKRIFAT JAWA SANGKAN PARANING DUMADI Eksplorasi Sufistik Konsep Mengenal Diri dalam Pustaka Islam Kejawen Kunci Swarga Miftahul Djanati Nur Kolis, Ph.D. CV. NATA KARYA ILMU MAKRIFAT JAWA SANGKAN PARANING DUMADI Eksplorasi Sufistik Konsep Mengenal Diri dalam Pustaka Islam Kejawen Kunci Swarga Miftahul Djanati Penulis : Hak Cipta © Nur Kolis, Ph.D. ISBN : 978-602-5774-11-9 Layout : Team Nata Karya Desain Sampul: Team Nata Karya Hak Terbit © 2018, Penerbit : CV. Nata Karya Jl. Pramuka 139 Ponorogo Telp. 085232813769 Email : [email protected] Cetakan Pertama, 2018 Perpustakaan Nasional : Katalog Dalam Terbitan (KDT) 260 halaman, 14,5 x 21 cm Dilarang keras mengutip, menjiplak, memfotocopi, atau memperbanyak dalam bentuk apa pun, baik sebagian maupun keseluruhan isi buku ini, serta memperjualbelikannya tanpa izin tertulis dari penerbit . KATA PENGANTAR بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم Segala puji bagi Allah Tuhan Yang Maha Kuasa, atas segala limpahan nikmat, hidâyah serta taufîq-Nya, sehingga penulis bisa menyelesaikan buku ini. Shalawat dan salam semoga senantiasa dilimpahkan kepada rasul-Nya, yang menjadi uswah hasanah bagi seluruh umat. Buku ini merupakan bagian penting dari pengembangan khazanah Islam di Nusantara yang berhubungan dengan ranah kehidupan mistis masyarakat Jawa, khususnya yang berhubungan dengan pustaka kuno yang dikaji oleh pengamal ajaran mistik Islam kejawen, yaitu ilmu mengenal diri yang dikemas dalam kaweruh sangkan paraning dumadi. Dalam naskah Kunci Swarga Miftahul Djanati terdapat suatu upaya orang Jawa untuk menarik teori tasawuf ke ranah pengamalan praktis dengan menggunakan cara pandang dengan lebih menekankan aspek esoterikal dalam perilaku kehidupan sehari-hari masyarakat Jawa, khususnya dalam memandang hubungan hamba dengan Tuhan dan alam semesta. Tentu saja penekanan aspek kualitas personal manusia sempurna (insan kamil) dikedepankan. -

Spectacle, Speculation, and the Hyperspace of Sovereignty

8 Hyperbuilding: Spectacle, Speculation, and the Hyperspace of Sovereignty Aihwa Ong The Chinese love the monumental ambition …. CCTV headquarters is an ambi- tious building. It was conceived at the same time that the design competition for Ground Zero took place – not in backward-looking US, but in the parallel universe of China. In communism, engineering has a high status, its laws resonating with Marxian wheels of history. Rem Koolhaas and OMA (2004: 129) Urban Spectacles The proliferation of metropolitan spectacles in Asia indexes a new cultural regime as major cities race to attain even more striking skylines. Beijing’s cluster of Olympic landmarks, Shanghai’s TV tower, Hong Kong’s forest of corporate towers, Singapore’s Marina Sands complex, and super-tall Burj Khalifa in Dubai are urban spectaculars that evoke the “technological sublime.” Frederic Jameson famously made the claim that the postmodern sublime has dissolved Marxian historical consciousness, but nowhere did he consider the role of architectural sublime in indexing a different kind of historical consciousness, one of national arrival on the global stage (Jameson 1991: 32–8). Despite the 2008–9 economic downturn, Shanghai’s urban transformation for the 2010 World Expo will exceed Beijing’s makeover for the 2008 Olympics.1 Spectacular architecture is often viewed as the handiwork of corporate capital in the colonization of urban markets. For instance, Anthony King and Abidin Kusno, writing about “On Be(ij)ing in the world,” argue that the rise of cutting-edge buildings in Beijing is an instantiation of postmodern globalization transforming the Chinese capital into a “transnational Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global, First Edition. -

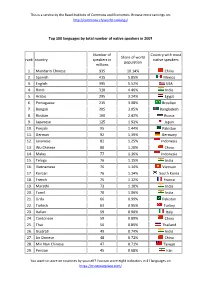

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Women and the Law Reprinted Congressional

WOMEN AND THE LAW REPRINTED FROM THE 2007 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 40–784 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:14 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\40784.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana MICHAEL M. HONDA, California CARL LEVIN, Michigan TOM UDALL, New Mexico DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey MEL MARTINEZ, Florida EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS PAULA DOBRIANSKY, Department of State CHRISTOPHER R. HILL, Department of State HOWARD M. RADZELY, Department of Labor DOUGLAS GROB, Staff Director MURRAY SCOT TANNER, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:14 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\40784.TXT DEIDRE C O N T E N T S Page Status of Women ............................................................................................. -

Recent Articles from the China Journal of System Engineering Prepared

Recent Articles from the China Journal of System Engineering Prepared by the University of Washington Quantum System Engineering (QSE) Group.1 Bibliography [1] Mu A-Hua, Zhou Shao-Lei, and Yu Xiao-Li. Research on fast self-adaptive genetic algorithm and its simulation. Journal of System Simulation, 16(1):122 – 5, 2004. [2] Guan Ai-Jie, Yu Da-Tai, Wang Yun-Ji, An Yue-Sheng, and Lan Rong-Qin. Simulation of recon-sat reconing process and evaluation of reconing effect. Journal of System Simulation, 16(10):2261 – 3, 2004. [3] Hao Ai-Min, Pang Guo-Feng, and Ji Yu-Chun. Study and implementation for fidelity of air roaming system above the virtual mount qomolangma. Journal of System Simulation, 12(4):356 – 9, 2000. [4] Sui Ai-Na, Wu Wei, and Zhao Qin-Ping. The analysis of the theory and technology on virtual assembly and virtual prototype. Journal of System Simulation, 12(4):386 – 8, 2000. [5] Xu An, Fan Xiu-Min, Hong Xin, Cheng Jian, and Huang Wei-Dong. Research and development on interactive simulation system for astronauts walking in the outer space. Journal of System Simulation, 16(9):1953 – 6, Sept. 2004. [6] Zhang An and Zhang Yao-Zhong. Study on effectiveness top analysis of group air-to-ground aviation weapon system. Journal of System Simulation, 14(9):1225 – 8, Sept. 2002. [7] Zhang An, He Sheng-Qiang, and Lv Ming-Qiang. Modeling simulation of group air-to-ground attack-defense confrontation system. Journal of System Simulation, 16(6):1245 – 8, 2004. [8] Wu An-Bo, Wang Jian-Hua, Geng Ying-San, and Wang Xiao-Feng. -

Ming China As a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2018 Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duan, Weicong, "Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1719. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Dissertation Examination Committee: Steven B. Miles, Chair Christine Johnson Peter Kastor Zhao Ma Hayrettin Yücesoy Ming China as a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 by Weicong Duan A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 St. Louis, Missouri © 2018, -

TITLE Secret World of the Forbidden City: Splendors from Imperial China, 1644-1911 and Change and Continuity: Chinese Americans in California

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 480 599 SO 035 272 TITLE Secret World of the Forbidden City: Splendors from Imperial China, 1644-1911 and Change and Continuity: Chinese Americans in California. Exhibition Information and Curriculum Guide for Teachers Grades 2-11. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 101p.; Prepared by the Oakland Museum of California Education Department. Color transparencies may not reproduce adequately. AVAILABLE FROM Oakland Museum of California, 100 Oak Street, Oakland, CA 94607-4892. Tel: 510-238-2200; Web site: http://www.museumca.org/exhibit/exhib_forbiddencity.html. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Art Education; *Chinese Americans; *Chinese Culture; Curriculum Enrichment; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; Exhibits; Foreign Countries; Global Education; *Museums; State Standards; *Visual Arts IDENTIFIERS California; *China; *Chinese Art; Chinese Civilization; Cultural Resources ABSTRACT The materials in this curriculum guide were designed to prepare teachers and students in grades 2-11 for the "Secret World of the Forbidden City: Splendors from China's Imperial Palace 1644-1911" exhibition at the Oakland Museum of California Education Department, to inform teachers and students about Imperial China, and to illuminate the continuing traditions of U.S. Chinese people in California. The guide includes a detailed table showing grade level recommendations and connections to the State of California Content Standards and Visual Arts Framework. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise).