Spectacle, Speculation, and the Hyperspace of Sovereignty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beijing City Day Tour to Forbidden City and Temple of Heaven

www.lilysunchinatours.com Beijing City Day Tour to Forbidden City and Temple of Heaven Basics Tour Code: LCT - BJ - 1D - 04 Duration: 1 Day Attractions: Forbidden City, Temple of Heaven, Summer Palace, Tian’anmen Square Overview: Embark on a journey to four major classic attractions in Beijing in a single day. Take the morning to explore the palatial and extravagant Forbidden City and the biggest city square in the world - Tian’anmen Square. In the afternoon, head for the old royal garden of Summer Palace and Temple of Heaven, the very place where emperors from Ming and Qing Dynasties held grand sacrifice ceremonies to the heaven. Highlights Stroll on the Tian’anmen Square and listen to the stories behind all the monuments, gates, museums and halls. Marvel at the exquisite Forbidden City - the largest palace complex in the world. Enjoy a peaceful time in Summer Palace. Meet a lot of Beijing local people in Temple of Heaven; Satisfy your tongue with a meal full of Beijing delicacies. Itinerary Date Starting Time Destination Day 1 09:00 a.m Forbidden City, Temple of Heaven, Summer Palace, Tian’anmen Square After breakfast, your tour expert and guide will take you to the first destination of the day - Tel: +86 18629295068 1 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] www.lilysunchinatours.com Tian’anmen Square. Seated in the center of Beijing, the square is well-known to be the largest city square in the world. The fact is the Tian’anmen Square is also a witness of numerous historical events and changes. At present, the square has become a place hosting a lot of monuments, museums, halls and the grand celebrations and military parades. -

Blue Territorialization of Asian Power

PROOF 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Buoyancy 12 13 Blue Territorialization 14 of Asian Power 15 16 AIHWA ONG 17 18 19 20 21 Are nations frmly delimited by national terrain? 22 Can sovereignty be expanded through the zoning of ocean and sky? 23 24 What are the implications of sovereign buoyancy for the world order? 25 26 27 Fixed and Contained? 28 Our notion of the nation- state as a physically fxed territoriality contained 29 by its formally delineated bound aries is increasingly difcult to uphold. It ap- 30 pears that the late twentieth- century global order is turning out to have been 31 a brief interregnum of agreed- upon sovereign power as contained within fxed 32 national borders. The League of Nations frst proposed an international sys- 33 tem of nation- states in the 1930s, and a global arrangement was formalized in 34 the aftermath of the Second World War. Defeated countries and newly inde - 35 pen dent ones were recognized as in de pen dent nation- states each with its own 36 politico- legal territoriality. Nevertheless, the requisite po liti cal infrastructure 37 of formal government with its own territoriality was not fully realized every- 38 where, and on some continents (with decolonized states or former Communist 39 218-85414_ch01_1P.indd 191 12/03/20 4:23 AM PROOF 1 Bloc countries), many nation- states have been challenged and fragmented by 2 breakaway groups, po liti cal uprisings, or drug cartels. The model of a sover- 3 eign nation- state with fxed physical borders may have a less stable temporality 4 than we imagined. -

TITLE Secret World of the Forbidden City: Splendors from Imperial China, 1644-1911 and Change and Continuity: Chinese Americans in California

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 480 599 SO 035 272 TITLE Secret World of the Forbidden City: Splendors from Imperial China, 1644-1911 and Change and Continuity: Chinese Americans in California. Exhibition Information and Curriculum Guide for Teachers Grades 2-11. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 101p.; Prepared by the Oakland Museum of California Education Department. Color transparencies may not reproduce adequately. AVAILABLE FROM Oakland Museum of California, 100 Oak Street, Oakland, CA 94607-4892. Tel: 510-238-2200; Web site: http://www.museumca.org/exhibit/exhib_forbiddencity.html. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Art Education; *Chinese Americans; *Chinese Culture; Curriculum Enrichment; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; Exhibits; Foreign Countries; Global Education; *Museums; State Standards; *Visual Arts IDENTIFIERS California; *China; *Chinese Art; Chinese Civilization; Cultural Resources ABSTRACT The materials in this curriculum guide were designed to prepare teachers and students in grades 2-11 for the "Secret World of the Forbidden City: Splendors from China's Imperial Palace 1644-1911" exhibition at the Oakland Museum of California Education Department, to inform teachers and students about Imperial China, and to illuminate the continuing traditions of U.S. Chinese people in California. The guide includes a detailed table showing grade level recommendations and connections to the State of California Content Standards and Visual Arts Framework. -

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Ruizhong Ding aus Qishan, VR. China Bonn, 2019 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Dr. Manfred Hutter, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kubin, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Betreuer und Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Ralph Kauz, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Veronika Veit, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung:22.07.2019 Acknowledgements Currently, when this dissertation is finished, I look out of the window with joyfulness and I would like to express many words to all of you who helped me. Prof. Wolfgang Kubin accepted me as his Ph.D student and in these years he warmly helped me a lot, not only with my research but also with my life. In every meeting, I am impressed by his personality and erudition deeply. I remember one time in his seminar he pointed out my minor errors in the speech paper frankly and patiently. I am indulged in his beautiful German and brilliant poetry. His translations are full of insightful wisdom. Every time when I meet him, I hope it is a long time. I am so grateful that Prof. Ralph Kauz in the past years gave me unlimited help. In his seminars, his academic methods and sights opened my horizons. Usually, he supported and encouraged me to study more fields of research. -

Global Imaginaries and Global Capital

GLOBAL IMAGINARIES ideas of cultural difference through AND GLOBAL CAPITAL: Balibar’s notion of “neo-racism,” and Žižek ’s conception of multiculturalism. LAWRENCE CHUA’S GOLD Gold by the Inch illuminates how spaces BY THE INCH AND SPACES of global capitalism manage and OF GLOBAL BELONGING appropriate the desire to belong as a means of producing surplus labor populations and consumer subjects. Christopher Patterson 1 Introduction Abstract THE STRAITS TIMES, The unnamed narrator in Lawrence SINGAPORE, April 28, 1990— Chua’s novel Gold by the Inch is multiply Wijit Potha, a 28-year-old queered. He appears to the reader as a migrant worker from Thailand, gay Thai/Malay migrant of Chinese was found dead this morning by descent living in the United States. As a fellow workers who shared his traveler, his encounters with episodes of spare living quarters near a sexual desire lead him to different notions construction site at Tanjong of belonging as his race, class, and Pagar. (Chua 1998: 3) sexuality travel with him, marking him as an outsider from one space to another. These opening lines of Laurence Chua’s Likewise, every instance of mobility Gold by the Inch cite the daily broadsheet challenges his identity, allowing him to newspaper, The Strait Times . They provide bear witness to unique forms of structural evidence for an underclass of migrant violence relative to whichever locality he workers, coded within a language of happens to be in. In short, Chua’s superstition and commerce. The article narrator is faced with oppressions based reveals that “18 Thais, nearly all of them on radical assumptions by the outside construction workers with no previous world that utilize his race, gender, symptoms of illness, have died in their sexuality, and American cultural identity sleep in Singapore” (Chua 1998: 3). -

The Development and Status of Human Geography in Malaysia

Japanese Journal of Human Geography 60―6(2008) Th e Development and Status of Human Geography in Malaysia LEE Boon Th ong I Introduction II The historical proclivity towards human geography III Trends in teaching interests in human geography in UM IV Research and publication in human geography in UM V The state of human geography in Malaysia VI Some concluding comments Keywords : Geography, Human Geography, curriculum, research, publications. I Introduction There are six universities in Malaysia offering courses in geography. However, when the subject of human geography, or for that matter, geography as a discipline, is broached, there are effec- tively only three tertiary institutions that offer the subject to undergraduate students. These three tertiary institutions are : firstly, the Department of Geography, University of Malaya( UM), located in Kuala Lumpur, the capital city ; secondly, the Geography Programme in Universiti Ke- bangsaan Malaysia( UKM) or the National University of Malaysia, located in Bangi, just outside Kuala Lumpur ; and thirdly, the Geography Section in Universiti Sains Malaysia( USM) in Penang in the north of the country.( USM was formerly known as University of Pulau Pinang). A fourth university that offers some courses in human geography is Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris( UPSI), a for- mer teachers’ training institute―turned university in 1997. However, given its orientation towards teacher training and education to fulfil the national aspiration to have graduate teachers in all schools, only basic human geography courses are conducted. Two other universities, Universiti Malaysia Sabah( UMS), which was set up in 1994 and Universiti Utara Malaysia( UUM), set up in 1984 offer a token course on population resource and geography of tourism respectively. -

Global Assemblages, Anthropological Problems 3 Stephen J

GLOBAL ASSEMBLAGES GLOBAL ASSEMBLAGES Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems EDITED BY AIHWA ONG AND STEPHEN J. COLLIER ©ȱ2005ȱbyȱBlackwellȱPublishingȱLtdȱ ȱ BLACKWELLȱPUBLISHINGȱ 350ȱMainȱStreet,ȱMalden,ȱMAȱ02148Ȭ5020,ȱUSAȱ 9600ȱGarsingtonȱRoad,ȱOxfordȱOX4ȱ2DQ,ȱUKȱ 550ȱSwanstonȱStreet,ȱCarlton,ȱVictoriaȱ3053,ȱAustraliaȱ ȱ TheȱrightȱofȱAihwaȱOngȱandȱStephenȱJ.ȱCollierȱtoȱbeȱidentifiedȱasȱtheȱAuthorsȱofȱtheȱEditorialȱMaterialȱ inȱthisȱWorkȱhasȱbeenȱassertedȱinȱaccordanceȱwithȱtheȱUKȱCopyright,ȱDesigns,ȱandȱPatentsȱActȱ1988.ȱ ȱ Allȱrightsȱreserved.ȱNoȱpartȱofȱthisȱpublicationȱmayȱbeȱreproduced,ȱstoredȱinȱaȱretrievalȱsystem,ȱorȱ transmitted,ȱinȱanyȱformȱorȱbyȱanyȱmeans,ȱelectronic,ȱmechanical,ȱphotocopying,ȱrecordingȱorȱ otherwise,ȱexceptȱasȱpermittedȱbyȱtheȱUKȱCopyright,ȱDesigns,ȱandȱPatentsȱActȱ1988,ȱwithoutȱtheȱpriorȱ permissionȱofȱtheȱpublisher.ȱ ȱ Firstȱpublishedȱ2005ȱbyȱBlackwellȱPublishingȱLtdȱ ȱ 4 2007 ȱ LibraryȱofȱCongressȱCatalogingȬinȬPublicationȱDataȱ ȱ Globalȱassemblagesȱ:ȱtechnology,ȱpolitics,ȱandȱethicsȱasȱanthropologicalȱ problemsȱ/ȱeditedȱbyȱAihwaȱOngȱandȱStephenȱJ.ȱCollier.ȱ p.ȱcm.ȱ Includesȱbibliographicalȱreferencesȱandȱindex.ȱ ISBNȱ0Ȭ631Ȭ23175Ȭ7ȱ(clothȱ:ȱalk.ȱpaper)–ISBNȱ1Ȭ4051Ȭ2358Ȭ3ȱ(pbk.ȱ:ȱalk.ȱpaper)ȱ 1.ȱSocialȱchange.ȱȱȱ2.ȱGlobalization–Socialȱaspects.ȱȱȱ3.ȱTechnologicalȱinnovations–Socialȱaspects.ȱ 4.ȱDiscoveriesȱinȱscience–Socialȱaspects.ȱȱȱI.ȱOng,ȱAihwa.ȱȱȱII.ȱCollier,ȱStephenȱJ.ȱ HM831.G49ȱ2005ȱ 303.4–dc22ȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ2003026675ȱ ȱ ISBNȬ13:ȱ978Ȭ0Ȭ631Ȭ23175Ȭ2ȱ(clothȱ:ȱalk.ȱpaper)–ISBNȬ13:ȱ978Ȭ1Ȭ4051Ȭ2358Ȭ7ȱ(pbk.ȱ:ȱalk.ȱpaper)ȱ -

In Conversation with Professor Aihwa Ong 21 May 2010, Singapore

Sinha & Ong In Conversation 95 KROEBER ANTHROPOLOGICAL SOCIETY, 100(1): 95-103 In Conversation with Professor Aihwa Ong 21 May 2010, Singapore Aihwa Ong, University of California, Berkeley Interviewed by Vineeta Sinha , National University of Singapore Vineeta Sinha (VS): So you went to the United States to study English and the fine arts. Why did you switch to anthropology? What attracted you to anthropology? Aihwa Ong (AO): When I first arrived at Barnard College in New York City, situated across the street from Columbia University, the place was taken over by students demonstrating against the “secret” bombings in Cambodia. Nevertheless, in the midst of this war, I found myself, in a day-to-day sense, having to explain who I was. After many months of sharing a dorm room, my roommate still described me simply as an “Asian.” Then I took an Anthropology 101 class where a graduate student demonstrated the art of stone tool making, and something clicked in my head. Anthropology seemed to me to be a field that combines the study of art, techniques, and language in cross- cultural contexts. It was an easy switch from English and the fine arts to anthropology. Two expatriate scholars – Clive Kessler and Joan Vincent – took me under their wing. At that time, there was very limited knowledge about Southeast Asia. VS: Do you think things are different today in an American context as far as the lack of awareness about the specificity of Southeast Asian experiences is concerned? AO: In the 1970s, the Southeast Asian field focused on indigenous political systems, a perspective shaped by Stanley Tambiah and Benedict Anderson. -

The Organization of the Gallery of Ancient Relics (Guwu Chenliesuo) Before 1925 — in Commemoration of the 100Th Anniversary of the Gallery of Ancient Relics

The Organization of The Gallery of Ancient Relics (Guwu Chenliesuo) before 1925 — in Commemoration of The 100th Anniversary of The Gallery of Ancient Relics Wu Shizhou The article Chinese appears Abstract: In accordance to The Conditions of Preferential Treatment of The Qing Royal Family the from page 006 to 015. ancient relics preserved in the imperial residences in Rehe and Fengtian got moved back to the Forbidden City with the Boxer Indemnity refunded by the foreign invaders after The Republic of China was founded. The Gallery of Ancient Relics (Guwu Chenliesuo) which was based on the Hall of Martial Valor (Wuying Dian) and Hall of Literary Glory (Wenhua Dian) was officially set up in February, 1924. However, as stipulated in the The Conditions of Preferential Treatment of The Qing Royal Family, all the private property of the Qing Court including the objects in the imperial residences of Rehe and Fengtian and the contents of the Forbidden City should be protected by the Government of The Republic of China. It has been tacitly admitted that the Qing Court was the original owner of the antiques. All the items that were back to the Forbidden City were checked before acceptance and endorsed by the imperial commissioners of The Interior Ministry that was closely linked with The Qing Court, which made it possible for the Qing Court Collected antiques to be purchased by the government in a peaceful way. But the government of the Republic of China could not afford the total objects at once because of financial shortage then, so it was agreed by both that the treasures were temporarily maintained in The Gallery of Ancient Relics (Guwu Chenliesuo) until they were fully paid for by the government of that time. -

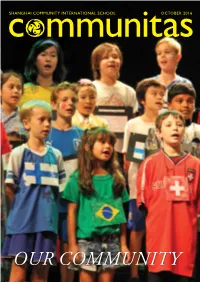

Our Community Table of Contents

SHANGHAI COMMUNITY INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL OCTOBER 2016 OUR COMMUNITY TABLE OF CONTENTS P. 4 // Director of School’s Letter Features P. 5-9 // Theme Feature Our SCIS Community Working Towards our Missions with the Learner Profile Building Community through the PYP and International Mindedness P. 16-17 // Community Feature Celebrating Sportsmanship P. 10-13 // Curriculum Building Bridges and Making Connections 24-25 // China Host Culture through Language and Culture Dragon Culture in China Building a Sense of Community P. 34-36 // Art Gallery in the Early Years Dowload our App! Hongqiao & Pudong Campus SHOP ANYWHERE, ANYTIME Welcome Change & Learning Together Your Online Expat Supermarket - www.epermarket.com P. 18-19 // PUDONG Campus Highlight United Nation’s Campus International Day of Peace Highlights P. 20-21 // Hongqiao Campus Highlight The Class of 2017 Goes to Hainan P. 22-23 // Hongqiao ECE Campus Highlight Celebrating Peace at the ECE Campus P. 14-15 // Favorite Spot in The City Family Friendly and Good Food Community P. 26-27 // Teacher Spotlight Discovering a Passion for International Teaching P. 32-33 // Alumni Spotlight Coming Full Circle Sport Recap P. 28-29 // Partner Dragons Volleyball P. 37-39 // LanguageOne P. 30-31 // Family Spotlight 5 Healthy Habits for Kids to Prevent The Vlas Family Cold and Flu in the Coming Winter The Reach for Better Health 4 DIRECTOR OF SCHOOL’S LETTER THEME FEATURE 5 Shanghai Community International School (SCIS) first opened its doors in 1996. Twenty years on and our success continues to be built upon the strong, quality relationships formed within our dynamic international OCTOBER 2016 school community of teachers, students, and parents. -

Inter-Asian Connections

Conference on Inter-Asian Connections Detail of migration map of Asia: courtesy UNHCR Conference Proceedings February 21-23, 2008 Dubai, United Arab Emirates Co-Organized by the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) and the Dubai School of Government (DSG) Funded by the Ford Foundation Sponsored by DSG, Zayed University, the University of Dubai, the National Bank of Dubai, and Dubai Properties INTRODUCTION This international conference brought together over one hundred fifty leading scholars from renowned universities to explore an exciting new frontier of “Inter-Asian” research. The conference was organized around eleven concurrent workshops featuring innovative research from the social sciences and related disciplines on themes of particular relevance across Asia. Workshop themes, directors, and participants were selected by an SSRC committee in a highly competitive process: the conference organizers received 105 applications for workshop directors and 582 applications for workshop participants. In addition to the eleven workshops, the conference also showcased the work of the South Asia Regional Fellowship Program (SARFP), bringing together fellows who had been awarded collaborative grants to work on inter-country projects in the South Asia region. The structure and schedule of the conference were designed to enable intensive working group interactions on a specific research theme, as well as broader interactions on topics of mutual interest and concern to all participants. Accordingly, a public keynote panel and plenaries addressing different aspects of Inter-Asian research were open to all participants as well as the general public. The concluding day of the conference brought all the workshops together in a public presentation and exchange of research agendas that emerged over the course of the deliberations in Dubai. -

The Ming Dynasty

The East Asian World 1400–1800 Key Events As you read this chapter, look for the key events in the history of the East Asian world. • China closed its doors to the Europeans during the period of exploration between 1500 and 1800. • The Ming and Qing dynasties produced blue-and-white porcelain and new literary forms. • Emperor Yong Le began renovations on the Imperial City, which was expanded by succeeding emperors. The Impact Today The events that occurred during this time still impact our lives today. • China today exports more goods than it imports. • Chinese porcelain is collected and admired throughout the world. • The Forbidden City in China is an architectural wonder that continues to attract people from around the world. • Relations with China today still require diplomacy and skill. World History Video The Chapter 16 video, “The Samurai,” chronicles the role of the warrior class in Japanese history. 1514 Portuguese arrive in China Chinese sailing ship 1400 1435 1470 1505 1540 1575 1405 1550 Zheng He Ming dynasty begins voyages flourishes of exploration Ming dynasty porcelain bowl 482 Art or Photo here The Forbidden City in the heart of Beijing contains hundreds of buildings. 1796 1598 1644 1750 White Lotus HISTORY Japanese Last Ming Edo is one of rebellion unification emperor the world’s weakens Qing begins dies largest cities dynasty Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World History Web site at 1610 1645 1680 1715 1750 1785 tx.wh.glencoe.com and click on Chapter 16–Chapter Overview to preview chapter information. 1603 1661 1793 Tokugawa Emperor Britain’s King rule begins Kangxi begins George III sends “Great 61-year reign trade mission Peace” to China Japanese samurai 483 Emperor Qianlong The meeting of Emperor Qianlong and Lord George Macartney Mission to China n 1793, a British official named Lord George Macartney led a mission on behalf of King George III to China.