Women and the Law Reprinted Congressional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immigration Coverage in Chinese-Language Newspapers Acknowledgments This Report Was Made Possible in Part by a Grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York

Building the National Will to Expand Opportunity in America Media Content Analysis: Immigration Coverage in Chinese-Language Newspapers Acknowledgments This report was made possible in part by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. Project support from Unbound Philanthropy and the Four Freedoms Fund at Public Interest Projects, Inc. (PIP) also helped support this research and collateral communications materials. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. The research and writing of this report was performed by New America Media, under the direction of Jun Wang and Rong Xiaoqing. Further contributions were made by The Opportunity Agenda. Ed - iting was done by Laura Morris, with layout and design by Element Group, New York. About The Opportunity Agenda The Opportunity Agenda was founded in 2004 with the mission of building the national will to expand opportunity in America. Focused on moving hearts, minds and policy over time, the organization works closely with social justice organizations, leaders, and movements to advocate for solutions that expand opportunity for everyone. Through active partnerships, The Opportunity Agenda uses communications and media to understand and influence public opinion; synthesizes and translates research on barriers to opportunity and promising solutions; and identifies and advocates for policies that improve people’s lives. To learn more about The Opportunity Agenda, go to our website at www.opportunityagenda.org. The Opportunity Agenda is a project of the Tides Center. Table of Contents Foreword 3 1. Major Findings 4 2. Research Methodology 4 3. Article Classification 5 4. A Closer Look at the Coverage 7 5. -

Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media

China Perspectives 2018/3 | 2018 Twenty Years After: Hong Kong's Changes and Challenges under China's Rule Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media Francis L. F. Lee Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.8009 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2018 Number of pages: 9-18 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Francis L. F. Lee, “Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media”, China Perspectives [Online], 2018/3 | 2018, Online since 01 September 2018, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 8009 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media FRANCIS L. F. LEE ABSTRACT: Most observers argued that press freedom in Hong Kong has been declining continually over the past 15 years. This article examines the problem of press freedom from the perspective of the political economy of the media. According to conventional understanding, the Chinese government has exerted indirect influence over the Hong Kong media through co-opting media owners, most of whom were entrepreneurs with ample business interests in the mainland. At the same time, there were internal tensions within the political economic system. The latter opened up a space of resistance for media practitioners and thus helped the media system as a whole to maintain a degree of relative autonomy from the power centre. However, into the 2010s, the media landscape has undergone several significant changes, especially the worsening media business environment and the growth of digital media technologies. -

Media Capture with Chinese Characteristics

JOU0010.1177/1464884917724632JournalismBelair-Gagnon et al. 724632research-article2017 Article Journalism 1 –17 Media capture with Chinese © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: characteristics: Changing sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917724632DOI: 10.1177/1464884917724632 patterns in Hong Kong’s journals.sagepub.com/home/jou news media system Nicholas Frisch Yale University, USA Valerie Belair-Gagnon University of Minnesota, USA Colin Agur University of Minnesota, USA Abstract In the Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong, a former British territory in southern China returned to the People’s Republic as a semi-autonomous enclave in 1997, media capture has distinct characteristics. On one hand, Hong Kong offers a case of media capture in an uncensored media sector and open market economy similar to those of Western industrialized democracies. Yet Hong Kong’s comparatively small size, close proximity, and broad economic exposure to the authoritarian markets and politics of neighboring Mainland China, which practices strict censorship, place unique pressures on Hong Kong’s nominally free press. Building on the literature on media and politics in Hong Kong post-handover and drawing on interviews with journalists in Hong Kong, this article examines the dynamics of media capture in Hong Kong. It highlights how corporate-owned legacy media outlets are increasingly deferential to the Beijing government’s news agenda, while social media is fostering alternative spaces for more skeptical and aggressive voices. This article develops a scholarly vocabulary to describe media capture from the perspective of local journalists and from the academic literature on media and power in Hong Kong and China since 1997. -

28. Rights Defense and New Citizen's Movement

JOBNAME: EE10 Biddulph PAGE: 1 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Fri May 10 14:09:18 2019 28. Rights defense and new citizen’s movement Teng Biao 28.1 THE RISE OF THE RIGHTS DEFENSE MOVEMENT The ‘Rights Defense Movement’ (weiquan yundong) emerged in the early 2000s as a new focus of the Chinese democracy movement, succeeding the Xidan Democracy Wall movement of the late 1970s and the Tiananmen Democracy movement of 1989. It is a social movement ‘involving all social strata throughout the country and covering every aspect of human rights’ (Feng Chongyi 2009, p. 151), one in which Chinese citizens assert their constitutional and legal rights through lawful means and within the legal framework of the country. As Benney (2013, p. 12) notes, the term ‘weiquan’is used by different people to refer to different things in different contexts. Although Chinese rights defense lawyers have played a key role in defining and providing leadership to this emerging weiquan movement (Carnes 2006; Pils 2016), numerous non-lawyer activists and organizations are also involved in it. The discourse and activities of ‘rights defense’ (weiquan) originated in the 1990s, when some citizens began using the law to defend consumer rights. The 1990s also saw the early development of rural anti-tax movements, labor rights campaigns, women’s rights campaigns and an environmental movement. However, in a narrow sense as well as from a historical perspective, the term weiquan movement only refers to the rights campaigns that emerged after the Sun Zhigang incident in 2003 (Zhu Han 2016, pp. 55, 60). The Sun Zhigang incident not only marks the beginning of the rights defense movement; it also can be seen as one of its few successes. -

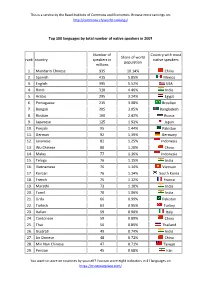

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Author: Works Won Immediate Acclaim

Thursday, November 1, 2018 CHINA DAILY HONG KONG EDITION 2 PAGE TWO Louis Cha (second left) poses with cast members of the filmThe Story of the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping meets with Louis Cha and his family in Beijing Louis Cha displays his novel Book and Sword, Gratitude and Revenge at his Great Heroes in 1960. PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY in 1983. LYU XIANGYOU / CHINA NEWS SERVICE office in Hong Kong in 2002. BOBBY YIP / FILE PHOTO / REUTERS Author: Works won immediate acclaim From page 1 transitions from the Song to Yuan years ago, said, “Despite relatively and Ming to Qing dynasties, and low salaries, Ming Pao is still a popu His ideals fascinated his publish explores topics including the ethnic lar choice for youngsters looking for ers abroad more than martial arts. conflict between Han and nonHan a job”. Christopher MacLehose, a veteran peoples, the collective memory Apart from its professionalism, he of the profession in London, pub under colonial rule, and broad and said another reason is that the news lished Legends of Condor Heroes in narrow nationalisms. paper is willing to recruit diversified the United Kingdom in February. According to Petrus Liu, associate talent, including Hui himself, who He said, “The story he tells is part of professor of comparative literature had never studied journalism his view and opinion. I think it’s at Boston University, Cha’s works before. inaccurate to simply call it martial contain an encyclopedic knowledge Tam Yiuchung, a Hong Kong dep arts fiction.” of traditional Chinese history, medi uty to the Standing Committee of the Albert Yeung Hingon, honorary cine, geography, cosmology and National People’s Congress, the coun chairman of the Hong Kong Novel even mathematics. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2003: China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong and Macau)

Page 1 of 66 China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau) Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 (Note: Also see the section for Tibet, the report for Hong Kong, and the report for Macau.) The People's Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which, as directed by the Constitution, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or Party) is the paramount source of power. Party members hold almost all top government, police, and military positions. Ultimate authority rests with the 24-member political bureau (Politburo) of the CCP and its 9-member standing committee. Leaders made a top priority of maintaining stability and social order and were committed to perpetuating the rule of the CCP and its hierarchy. Citizens lacked both the freedom peacefully to express opposition to the Party-led political system and the right to change their national leaders or form of government. Socialism continued to provide the theoretical underpinning of national politics, but Marxist economic planning has given way to pragmatism, and economic decentralization increased the authority of local officials. The Party's authority rested primarily on the Government's ability to maintain social stability; appeals to nationalism and patriotism; Party control of personnel, media, and the security apparatus; and continued improvement in the living standards of most of the country's 1.3 billion citizens. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, in practice, the Government and the CCP, at both the central and local levels, frequently interfered in the judicial process and directed verdicts in many high-profile cases. -

The Long Shadow of Chinese Censorship: How the Communist Party’S Media Restrictions Affect News Outlets Around the World

The Long Shadow of Chinese Censorship: How the Communist Party’s Media Restrictions Affect News Outlets Around the World A Report to the Center for International Media Assistance By Sarah Cook October 22, 2013 The Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA), at the National Endowment for Democracy, works to strengthen the support, raise the visibility, and improve the effectiveness of independent media development throughout the world. The Center provides information, builds networks, conducts research, and highlights the indispensable role independent media play in the creation and development of sustainable democracies. An important aspect of CIMA’s work is to research ways to attract additional U.S. private sector interest in and support for international media development. CIMA convenes working groups, discussions, and panels on a variety of topics in the field of media development and assistance. The center also issues reports and recommendations based on working group discussions and other investigations. These reports aim to provide policymakers, as well as donors and practitioners, with ideas for bolstering the effectiveness of media assistance. Don Podesta Interim Senior Director Center for International Media Assistance National Endowment for Democracy 1025 F Street, N.W., 8th Floor Washington, DC 20004 Phone: (202) 378-9700 Fax: (202) 378-9407 Email: [email protected] URL: http://cima.ned.org Design and Layout by Valerie Popper About the Author Sarah Cook Sarah Cook is a senior research analyst for East Asia at Freedom House. She manages the editorial team producing the China Media Bulletin, a biweekly news digest of media freedom developments related to the People’s Republic of China. -

Media Kit2019

Ming Pao Daily News | Western Edition MEDIA KIT 2019 Compared with Chinese Daily Newspaper Ming Pao Daily News has the highest numbers readers 309,359 Weekly Readership* *Source: Forward Research Group, Vancouver Chinese Media Survey 2018. Survey conducted October 2 to October 29, 2018 from a sample of 560 Chinese- Speaking adults aged 18 or older living in the Vancouver CMA. The result reported on the total sample are considered accurate +/- 0.5%, based on cell weighting Ming Pao is not just a newspaper | 1 Ming Pao Daily News | Western Edition About Ming Pao Daily News Ming Pao Daily News is not just a newspaper! MING PAO IS #1 ounded and headquartered in Hong Kong since 1959, Ming Pao Newspapers develops Finto a global media company with multiple subsidiaries across Asia and North America. In 1993, Ming Pao Newspapers established its branch in Canada, and has been serving the Chinese communities ever since. Our deep understanding of local, regional, and international issues has established our reputation as a leading authority on current a airs. Widely respected as an important voice, Ming Pao is recognized as one of the most in uential papers for Chinese professionals and business leaders throughout Western Canada. CREDIBILITY. TRUST. While continue to stay prominent in traditional channels, Ming Pao Newspapers also embarks With decades of continuous high-standard on a digital transformation – to create and journalism as well as dedication to the principle deliver editorial content across various platforms, of “Truth, Fairness, and Credibility”, channels, and formats. Ming Pao Newspapers has become the leading ethnic print media followed by a substantial Our teams consist of great talents including amount of readers.