The Investigation and Recording of Contemporary Taiwanese Calligraphers the Ink Trend Association and Xu Yong-Jin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006 Volkswagen Pro Tour Grand Finals Participating Players List (Updated As at 13/12/2006)

2006 Volkswagen Pro Tour Grand Finals Participating Players List (updated as at 13/12/2006) Men’s Singles Women’s Singles 01 MA Lin (CHN) ZHANG Yining (CHN) 02 WANG Liqin (CHN) WANG Yue Gu (SIN) 03 BOLL Timo (GER) *TIE Yana (HKG) 04 CHEN Qi (CHN) WANG Nan (CHN) 05 SAMSONOV Vladimir (BLR) LI Jia Wei (SIN) 06 WANG Hao (CHN) *JIANG Huajun (HKG) 07 HOU Yingchao (CHN) GUO Yan (CHN) 08 OH Sang Eun (KOR) LI Xiaoxia (CHN) 09 JOO Se Hyuk (KOR) LIU Jia (AUT) 10 CHEN Weixing (AUT) HIRANO Sayaka (JPN) 11 CHUAN Chih-Yuan (TPE) GAO Jun (USA) 12 SCHLAGER Werner (AUT) SHEN Yanfei (ESP) 13 *LI Ching (HKG) HIURA Reiko (JPN) 14 ELOI Damien (FRA) LI Jiao (NED) 15 GARDOS Robert (AUT) *ZHANG Rui (HKG) 16 KORBEL Petr (CZE) TAN MONFARDINI Wenling (ITA) Men’s Doubles Women’s Doubles 01 CHEN Qi / MA Lin (CHN) WANG Nan / ZHANG Yining (CHN) 02 CHEN Weixing / GARDOS Robert (AUT) *TIE Yana / ZHANG Rui (HKG) 03 *CHEUNG Yuk / LEUNG Chu Yan (HKG) GUO Yue / LI Xiaoxia (CHN) 04 *KO Lai Chak / LI Ching (HKG) LI Jia Wei / SUN Bei Bei (SIN) 05 BOLL Timo / SUSS Christian (GER) GAO Jun (USA) / SHEN Yanfei (ESP) 06 HAO Shuai / MA Long (CHN) HIRANO Sayaka / HIURA Reiko (JPN) 07 GAO Ning / YANG Zi (SIN) HEINE Veronika / LIU Jia (AUT) 08 AXELQVIST Johan / SVENSSON Robert (SWE) *LAU Sui Fei / LIN Ling (HKG) U21 Boys’ Singles U21 Girls’ Singles 01 *JIANG Tianyi (HKG) LI Qiangbing (AUT) 02 AXELQVIST Johan (SWE) POTA Georgina (HUN) 03 BAUM Patrick (GER) GRUNDISCH Carole (FRA) 04 BOBILLIER Loïc (FRA) RAMIREZ Sara (ESP) 05 JAKAB Janos (HUN) VACENOVSKA Iveta (CZE) 06 KIM Tae Hoon (KOR) *YU Kwok See (HKG) 07 MATSUMOTO Cazuo (BRA) HEINE Veronika (AUT) 08 DURAN Marc (ESP) PROKHOROVA Yulia (RUS) . -

Special Article 3 an Interview with Chu Wen-Ching, Advisor & Director, Taipei Cultural Center, Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office in Japan

Special Article 3 An Interview with Chu Wen-Ching, Advisor & Director, Taipei Cultural Center, Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office in Japan By Japan SPOTLIGHT Editorial Section The last issue highlighted Japanese soft power. Soft power is in particular important in consolidating close diplomatic relations with a neighboring country. In this issue Japan SPOTLIGHT highlights Taiwan and Taiwan-Japan cultural exchanges in an interview with a senior Taiwanese expert on culture, Chu Wen- Ching, advisor and director at the Taipei Cultural Center. Q: How do you assess the current Japanese NHK programs can always be status of cultural exchanges seen in Taiwan, as Taiwanese Cable TV has between Taiwan and Japan? a contract with NHK. Japanese folk singers like Sachiko Kobayashi, Shinichi Mori, Chu: We have a very close relationship in Sayuri Ishikawa, and Hiroshi Itsuki are also terms of trade and human exchanges. Our very popular. Masaharu Fukuyama, another bilateral trade totaled $62 billion last year famous Japanese singer, was recently and the number of tourists coming and appointed by the Taiwanese Tourism going between us will soon reach 4 million. Bureau as an ambassador of tourism for I have recently heard that there were a Taiwan and he is expected to volunteer to number of Taiwanese tourists who could introduce in his Japanese radio program not reserve air tickets to Japan to see the Taiwanese cuisine and culture to his cherry blossoms in April this year because audience. there were not enough vacancies. As this Taiwanese rock group Mayday and episode shows, human exchanges between Japanese pop-rock band flumpool are good us have recently been significantly friends, and often visit each other, while increasing. -

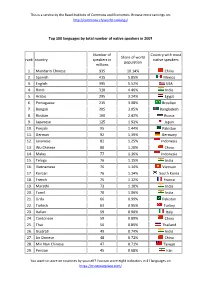

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Women and the Law Reprinted Congressional

WOMEN AND THE LAW REPRINTED FROM THE 2007 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 40–784 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:14 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\40784.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana MICHAEL M. HONDA, California CARL LEVIN, Michigan TOM UDALL, New Mexico DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey MEL MARTINEZ, Florida EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS PAULA DOBRIANSKY, Department of State CHRISTOPHER R. HILL, Department of State HOWARD M. RADZELY, Department of Labor DOUGLAS GROB, Staff Director MURRAY SCOT TANNER, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:14 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\40784.TXT DEIDRE C O N T E N T S Page Status of Women ............................................................................................. -

No. Venue Year Men's Team Women's Team Men's Singles

Asian Championships Results 1972 to 2007 No. Venue Year Men's Team Women's Men's Team Singles 1. Beijing 1972 Japan China HASEGAWA Nabuhiko (JPN) bt China bt Japan bt XI Enting (CHN) 2. Yokohama 1974 China Japan HASEGAWA Nabuhiko (JPN) Bt Japan Bt China bt XI Enting (CHN) 3. Pyongyang 1976 China Korea DPR LIANG Geliang (CHN) bt Japan bt China bt GUO Yuehua (CHN) 4. Kuala Lumpur 1978 China China GUO Yuehua(CHN) Bt Korea DPR Bt Korea DPR bt LIANG Geliang (CHN) 5. Calcutta 1980 China China SHI Zhihao (CHN) bt Japan bt Korea DPR bt XIE Saike (CHN) 6. Jakarta 1982 China China CAI Zhenhua (CHN) bt Japan bt Japan bt XIE Saike (CHN) 7. Islamabad 1984 China China XIE Saike (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt Korea DPR bt CHEN Longcan (CHN) 8. Shenzhen 1986 China China J1ANG Jialiang (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt Korea DPR bt TENG Yi (CHN) 9. Niigata 1988 China Korea R CHEN Longcan (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt Korea DPR Bt YOO Nam Kyu (KOR) 10. Kuala Lumpur 1990 China Korea R WANG Tao (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt Korea DPR bt MA Wenge (CHN) 11. New Delhi 1992 China Hong Kong XIE Chaojie (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt China bt KANG Hee Chan (KOR) 12. Tianjin 1994 China China KONG Linghui (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt Hong Kong bt LIU Guoliang (CHN) 13 Singapore 1996 Korea China Kong Linghui(CHN) Bt China Bt Hong Kong Bt Liu Guoliang(CHN) 14 Osaka 1998 China China WANG Liqin(CHN) Bt Korea R Bt Korea DPR Bt Seiko Iseki(JPN) 15 Doha 2000 China China CHIANG Peng-Lung(TPE) Bt Korea Bt Korea Bt MA Lin(CHN) 16 Bangkok 2003 China Bt China Bt Wang Hao(CHN) Chinese Taipei Hongkong,China Bt Tang Peng(CHN) 17 -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Mystical and Spiritual Worlds in Contemporary Taiwanese Art

Joni Low With Roots Skyward: Mystical and Spiritual Worlds in Contemporary Taiwanese Art he afternoon I visited the University of British Columbia (UBC) Museum of Anthropology’s exhibition (In)visible: The Spiritual TWorld of Taiwan through Contemporary Art (November 20, 2015–April 3, 2016), I serendipitously ran into Beau Dick, a renowned Kwakwaka’wakw chief and current artist-in-residence at UBC, whose exhibition was concurrently displayed at the nearby Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, also at UBC.1 In an unexpected yet meaningful encounter, Beau and a fellow artist, Vanessa Grondin, joined me on my walk through (In)visible. His presence completely transformed my experience of the exhibition, allowing me to draw parallels between the spiritual explorations of Indigenous Taiwanese artists and our Pacific Northwest coast First Nations artists and their deep connections to the land and traditional practices of both. It prompted me to think more deeply about the politics of representation and display and about the openness to spiritual questions in both contemporary art and anthropological frameworks in exhibition contexts. The Great Hall, Museum of Anthropology, UBC, Vancouver. The Museum of Anthropology, a handsome concrete and glass building perched atop a cliff in Point Grey, Vancouver, was designed by Arthur Erickson to acknowledge the cultural importance of Canada’s First Nations. Based on the layout of a Haida waterfront village, it brings together a diverse range of historic cultural architectures, from Haida post-and-beam structures to the torii style gates reminiscent of Japanese Shinto shrines. The back of the museum hosts the great hall, with a large a surface of glass that 98 Vol. -

Ran In-Ting's Watercolors

Ran In-Ting’s Watercolors East and West Mix in Images of Rural Taiwan May 28–August 14, 2011 Ran In-Ting (Chinese, Taiwan, 1903–1979) Dragon Dance, 1958 Watercolor (81.20) Gift of Margaret Carney Long and Howard Rusk Long in memory of the Boone County Long Family Ran In-Ting (Chinese, Taiwan, 1903–1979) Market Day, 1956 Watercolor (81.6) Gift of Margaret Carney Long and Howard Rusk Long in memory of the Boone County Long Family Mary Pixley Associate Curator of European and American Art his exhibition focuses on the art of the painter Ran In-Ting (Lan Yinding, 1903–1979), one of Taiwan’s most famous T artists. Born in Luodong town of Yilan county in northern Taiwan, he first learned ink painting from his father. After teach- ing art for several years, he spent four years studying painting with the important Japanese watercolor painter Ishikawa Kinichiro (1871–1945). Ran’s impressionistic watercolors portray a deeply felt record With a deep understanding of Chinese brushwork and the of life in Taiwan, touching on the natural beauty of rural life and elegant watercolor strokes of Ishikawa, Ran developed a unique vivacity of the suburban scene. Capturing the excitement of a style that emphasized the changes in fluidity of ink and water- dragon dance with loose and erratic strokes, the mystery and color. By mastering both wet and dry brush techniques, he suc- magic of the rice paddies with flowing pools of color, and the ceeded at deftly controlling the watery medium. Complementing shimmering foliage of the forests with a rainbow of colors and this with a wide variety of brushstrokes and the use of bold dextrous strokes, his paintings are a vivid interpretation of his colors, Ran created watercolors possessing an elegant richness homeland. -

Preliminary Research on Taiwanese Art Curriculum Design Based on Visual Culture

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Preliminary Research on Taiwanese Art Curriculum Design Based On Visual Culture Jui-Jung Chang Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Art Education Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1541 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Preliminary Research on Taiwanese Art Curriculum Design Based on Visual Culture By Jui-Jung Chang B.A. Chinese National Taiwanese Normal University 2002 Director: Dr. Pamela G. Taylor Art Education Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia April 2006 Acknowledgment I would like to thank my parents and my family for their unending love and support. I would also like to thank Dr. Taylor for her help and for her direction with this project. Last but not least, I would like to thank all of my friends in Richmond for their patience and love. Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................... iv Chapter I Introduction .................................................................................. 1 Chapter I1 Literature Review Postmodern Ideas of Education .................................................................. -

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Ruizhong Ding aus Qishan, VR. China Bonn, 2019 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Dr. Manfred Hutter, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kubin, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Betreuer und Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Ralph Kauz, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Veronika Veit, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung:22.07.2019 Acknowledgements Currently, when this dissertation is finished, I look out of the window with joyfulness and I would like to express many words to all of you who helped me. Prof. Wolfgang Kubin accepted me as his Ph.D student and in these years he warmly helped me a lot, not only with my research but also with my life. In every meeting, I am impressed by his personality and erudition deeply. I remember one time in his seminar he pointed out my minor errors in the speech paper frankly and patiently. I am indulged in his beautiful German and brilliant poetry. His translations are full of insightful wisdom. Every time when I meet him, I hope it is a long time. I am so grateful that Prof. Ralph Kauz in the past years gave me unlimited help. In his seminars, his academic methods and sights opened my horizons. Usually, he supported and encouraged me to study more fields of research. -

Exploring the Chinese Metal Scene in Contemporary Chinese Society (1996-2015)

"THE SCREAMING SUCCESSOR": EXPLORING THE CHINESE METAL SCENE IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE SOCIETY (1996-2015) Yu Zheng A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2016 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Kristen Rudisill © 2016 Yu Zheng All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This research project explores the characteristics and the trajectory of metal development in China and examines how various factors have influenced the localization of this music scene. I examine three significant roles – musicians, audiences, and mediators, and focus on the interaction between the localized Chinese metal scene and metal globalization. This thesis project uses multiple methods, including textual analysis, observation, surveys, and in-depth interviews. In this thesis, I illustrate an image of the Chinese metal scene, present the characteristics and the development of metal musicians, fans, and mediators in China, discuss their contributions to scene’s construction, and analyze various internal and external factors that influence the localization of metal in China. After that, I argue that the development and the localization of the metal scene in China goes through three stages, the emerging stage (1988-1996), the underground stage (1997-2005), the indie stage (2006-present), with Chinese characteristics. And, this localized trajectory is influenced by the accessibility of metal resources, the rapid economic growth, urbanization, and the progress of modernization in China, and the overall development of cultural industry and international cultural communication. iv For Yisheng and our unborn baby! v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to show my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Dr. -

Local Information

Local information Wikimania 2007 Taipei :: a Globe in Accord English • Deutsch • Français • Italiano • 荳袿ᣩ • Nederlands • Norsk (bokmål) • Português • Ο錮"(顔覓/ヮ翁) • Help translation Taipei is the capital of Republic of China, and is the largest city of Taiwan. It is the political, commercial, media, educational and pop cultural center of Taiwan. According to the ranking by Freedom House, Taiwan enjoys the most free government in Asia in 2006. Taiwan is rich in Chinese culture. The National Palace Museum in Taipei holds world's largest collection of Chinese artifacts, artworks and imperial archives. Because of these characteristics, many public institutions and private companies had set their headquarters in Taipei, making Taipei one of the most developed cities in Asia. Well developed in commercial, tourism and infrastructure, combined with a low consumers index, Taipei is a unique city of the world. You could find more information from the following three sections: Local Information Health, Regulations Main Units of General Weather safety, and Financial and Electricity Embassies Time Communications Page measurement Conversation Accessibility Customs Index 1. Weather - Local weather information. 2. Health and safety - Information regarding your health and safety◇where to find medical help. 3. Financial - Financial information like banks and ATMs. 4. Regulations and Customs - Regulations and customs information to help your trip. 5. Units of measurement - Units of measurement used by local people. 6. Electricity - Infromation regarding voltage. 7. Embassies - Information of embassies in Taiwan. 8. Time - Time zone, business hours, etc. 9. Communications - Information regarding making phone calls and get internet services. 10. General Conversation - General conversation tips. 1.