28. Rights Defense and New Citizen's Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Introduction Chinese Citizens Continue to Face Substantial Obstacles in Seeking Remedies to Government Actions That Violate Th

1 ACCESS TO JUSTICE Introduction Chinese citizens continue to face substantial obstacles in seeking remedies to government actions that violate their legal rights and constitutionally protected freedoms. International human rights standards require effective remedies for official violations of citi- zens’ rights. Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that ‘‘Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the funda- mental rights granted him by the constitution or by law.’’ 1 Article 2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which China has signed but not yet ratified, requires that all parties to the ICCPR ensure that persons whose rights or free- doms are violated ‘‘have an effective remedy, notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity.’’ 2 The Third Plenum and Judicial Reform The November 2013 Chinese Communist Party Central Com- mittee Third Plenum Decision on Certain Major Issues Regarding Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (Third Plenum Decision) con- tained several items relating to judicial system reform.3 In June 2014, the office of the Party’s Central Leading Small Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reform announced that six provinces and municipalities—Shanghai, Guangdong, Jilin, Hubei, Hainan, and Qinghai—would serve as pilot sites for certain judicial reforms, including divesting local governments of their control over local court funding and appointments and centralizing -

Young Feminist Activists in Present-Day China: a New Feminist Generation?

China Perspectives 2018/3 | 2018 Twenty Years After: Hong Kong's Changes and Challenges under China's Rule Young Feminist Activists in Present-Day China: A New Feminist Generation? Qi Wang Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8165 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2018 Number of pages: 59-68 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Qi Wang, « Young Feminist Activists in Present-Day China: A New Feminist Generation? », China Perspectives [Online], 2018/3 | 2018, Online since 01 September 2019, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8165 © All rights reserved Articles China perspectives Young Feminist Activists in Present-Day China A New Feminist Generation? QI WANG ABSTRACT: This article studies post-2000 Chinese feminist activism from a generational perspective. It operationalises three notions of gene- ration—generation as an age cohort, generation as a historical cohort, and “political generation”—to shed light on the question of generation and generational change in post-socialist Chinese feminism. The study shows how the younger generation of women have come to the forefront of feminist protest in China and how the historical conditions they live in have shaped their feminist outlook. In parallel, it examines how a “po- litical generation” emerges when feminists of different ages are drawn together by a shared political awakening and collaborate across age. KEYWORDS: -

Hu Jia on Behalf of the Silenced Voices of China and Tibet

Sakharov Prize 2008 Year for China Hu Jia On behalf of the silenced voices of China and Tibet Hu Jia and his wife, Zeng Jinyan, were nominated for last year's Sakharov Prize and were among the final three short-listed candidates. Hu Jia was consequently imprisoned and remains in prison to this day. Hu Jia is a prominent human rights activist who works on various issues including civil rights, environmental protection and AIDS advocacy. He was arrested shortly after his testimony on 26 November 2007 via conference call before the European Parliament's sub-committee on Human Rights. In his statement, he expressed his desire that 2008 be the “year of human rights in China”. He also pointed out that the Chinese national security department was creating a human rights disaster with one million people persecuted for fighting for human rights and many of them detained in prison, in camps or mental hospitals. He also said: "The irony is that one of the people in charge of organising the Olympics is the head of the Public Security Bureau in Beijing who is responsible for so many human rights violations. The promises of China are not being kept before the games." As a direct result of his address to members of the European Parliament, Hu Jia was arrested, charged with "inciting subversion of state power", and sentenced on 3 April 2008 to three-and-a-half years' in jail with one year denial of political rights. He was found guilty of writing articles about the human rights situation in the run-up to the Olympic Games. -

Women and the Law Reprinted Congressional

WOMEN AND THE LAW REPRINTED FROM THE 2007 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 40–784 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:14 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\40784.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana MICHAEL M. HONDA, California CARL LEVIN, Michigan TOM UDALL, New Mexico DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey MEL MARTINEZ, Florida EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS PAULA DOBRIANSKY, Department of State CHRISTOPHER R. HILL, Department of State HOWARD M. RADZELY, Department of Labor DOUGLAS GROB, Staff Director MURRAY SCOT TANNER, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:14 Feb 20, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\40784.TXT DEIDRE C O N T E N T S Page Status of Women ............................................................................................. -

The Broad and Sustained Offensive on Human Rights That Started After President Xi Jinping Took Power Five Years Ago Showed No Sign of Abating in 2017

JANUARY 2018 COUNTRY SUMMARY China The broad and sustained offensive on human rights that started after President Xi Jinping took power five years ago showed no sign of abating in 2017. The death of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo in a hospital under heavy guard in July highlighted the Chinese government’s deepening contempt for rights. The near future for human rights appears grim, especially as Xi is expected to remain in power at least until 2022. Foreign governments did little in 2017 to push back against China’s worsening rights record at home and abroad. The Chinese government, which already oversees one of the strictest online censorship regimes in the world, limited the provision of censorship circumvention tools and strengthened ideological control over education and mass media in 2017. Schools and state media incessantly tout the supremacy of the Chinese Communist Party, and, increasingly, of President Xi Jinping as “core” leader. Authorities subjected more human rights defenders—including foreigners—to show trials in 2017, airing excerpted forced confessions and court trials on state television and social media. Police ensured the detainees’ compliance by torturing some of them, denying them access to lawyers of their choice, and holding them incommunicado for months. In Xinjiang, a nominally autonomous region with 11 million Turkic Muslim Uyghurs, authorities stepped up mass surveillance and the security presence despite the lack of evidence demonstrating an organized threat. They also adopted new policies denying Uyghurs cultural and religious rights. Hong Kong’s human rights record took a dark turn. Hong Kong courts disqualified four pro-democracy lawmakers in July and jailed three prominent pro-democracy student leaders in August. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report 2019

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–743 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate JAMES P. MCGOVERN, Massachusetts, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Co-chair Chair JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TOM COTTON, Arkansas THOMAS SUOZZI, New York STEVE DAINES, Montana TOM MALINOWSKI, New Jersey TODD YOUNG, Indiana BEN MCADAMS, Utah DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California CHRISTOPHER SMITH, New Jersey JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon BRIAN MAST, Florida GARY PETERS, Michigan VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Department of State, To Be Appointed Department of Labor, To Be Appointed Department of Commerce, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed JONATHAN STIVERS, Staff Director PETER MATTIS, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT C O N T E N T S Page I. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2003: China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong and Macau)

Page 1 of 66 China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau) Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 (Note: Also see the section for Tibet, the report for Hong Kong, and the report for Macau.) The People's Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which, as directed by the Constitution, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or Party) is the paramount source of power. Party members hold almost all top government, police, and military positions. Ultimate authority rests with the 24-member political bureau (Politburo) of the CCP and its 9-member standing committee. Leaders made a top priority of maintaining stability and social order and were committed to perpetuating the rule of the CCP and its hierarchy. Citizens lacked both the freedom peacefully to express opposition to the Party-led political system and the right to change their national leaders or form of government. Socialism continued to provide the theoretical underpinning of national politics, but Marxist economic planning has given way to pragmatism, and economic decentralization increased the authority of local officials. The Party's authority rested primarily on the Government's ability to maintain social stability; appeals to nationalism and patriotism; Party control of personnel, media, and the security apparatus; and continued improvement in the living standards of most of the country's 1.3 billion citizens. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, in practice, the Government and the CCP, at both the central and local levels, frequently interfered in the judicial process and directed verdicts in many high-profile cases. -

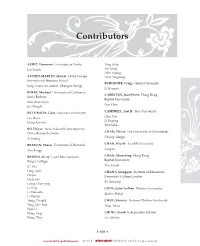

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman Or Degrading Treatment Or Punishment, Juan E

United Nations A/HRC/22/53/Add.4 General Assembly Distr.: General 12 March 2013 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Twenty-second session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Juan E. Méndez Addendum Observations on communications transmitted to Governments and replies received* * The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only. GE.13-11820 A/HRC/22/53/Add.4 Contents Paragraphs Page Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1–5 6 II. Observations by the Special Rapporteur ................................................................. 6–162 6 Angola ................................................................................................................ 6 6 Argentina ................................................................................................................ 7 7 Azerbajan ................................................................................................................ 8–9 7 Bahrain ................................................................................................................ 10–14 8 Bangladesh -

Gagging the Lawyers: China’S Crackdown on Human Rights Lawyers and Implica- Tions for U.S.-China Relations

GAGGING THE LAWYERS: CHINA’S CRACKDOWN ON HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYERS AND IMPLICA- TIONS FOR U.S.-CHINA RELATIONS HEARING BEFORE THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 28, 2017 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 26–342 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 08:36 Jan 29, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\26342.TXT PAT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Chairman CHRIS SMITH, New Jersey, Cochairman TOM COTTON, Arkansas ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina STEVE DAINES, Montana TRENT FRANKS, Arizona JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois TODD YOUNG, Indiana MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon TED LIEU, California GARY PETERS, Michigan ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Not yet appointed ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Staff Director PAUL B. PROTIC, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 08:36 Jan 29, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\26342.TXT PAT CO N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Opening Statement of Hon. Christopher Smith, a U.S. Representative From New Jersey; Cochairman, Congressional-Executive Commission on China .... 1 Statement of Hon. -

China's Pervasive Use of Torture

CHINA’S PERVASIVE USE OF TORTURE HEARING BEFORE THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 14, 2016 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 99–773 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 14:06 Jul 21, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\99773.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate CHRIS SMITH, New Jersey, Chairman MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Cochairman ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina TOM COTTON, Arkansas TRENT FRANKS, Arizona STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma DIANE BLACK, Tennessee BEN SASSE, Nebraska TIM WALZ, Minnesota DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon MICHAEL HONDA, California GARY PETERS, Michigan TED LIEU, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS CHRISTOPHER P. LU, Department of Labor SARAH SEWALL, Department of State STEFAN M. SELIG, Department of Commerce DANIEL R. RUSSEL, Department of State TOM MALINOWSKI, Department of State PAUL B. PROTIC, Staff Director ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 14:06 Jul 21, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\99773.TXT DEIDRE CO N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Opening Statement of Hon.