Towards a History of Architecture in the Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture at a First Glance Is Published by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science

... Contents Section 1 Introduction 7 Section 2 General Outline 9 2.1 Geography and language 9 2.2 Population and demographics 9 2.3 The role of the city 11 2.4 Organisation of government 13 2.5 Politics and society 14 2.6 Economic and social trends 15 Section 3 Cultural Policy 19 3.1 Historical perspective 19 3.2 Division of roles in tiers of government in funding of culture 20 3.3 Government spending on culture 21 3.3.1 Central government’s culture budget for 2013-2016 21 3.3.2 Municipal spending on culture 22 3.3.3 Impact of cuts on funded institutions 25 3.4 Cultural amenities: spread 26 3.5 Priority areas for the Dutch government 29 3.5.1 Cultural education and participation in cultural life 29 3.5.2 Talent development 30 3.5.3 The creative industries 30 3.5.4 Digitisation 31 3.5.5 Entrepreneurship 31 3.5.6 Internationalisation, regionalisation and urbanisation 32 3.6 Funding system 33 3.7 The national cultural funds 34 3.8 Cultural heritage 35 3.9 Media policy 38 Section 4 Trends in the culture sector 41 4.1 Financial trends 41 4.2 Trends in offering and visits 2009-2014 44 4.2.1 Size of the culture sector 44 4.2.2 Matthew effects? 45 4.3 Cultural reach 45 4.3.1 More frequent visits to popular performances 47 4.3.2 Reach of the visual arts 47 4.3.3 Interest in Dutch arts abroad 51 4.3.4 Cultural tourism 53 4.3.5 Culture via the media and internet 54 4.4 Arts and heritage practice 57 4.5 Cultural education 59 5 1 Introduction Culture at a first Glance is published by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. -

The Art of Staying Neutral the Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918

9 789053 568187 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 1 THE ART OF STAYING NEUTRAL abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 2 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 3 The Art of Staying Neutral The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918 Maartje M. Abbenhuis abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 4 Cover illustration: Dutch Border Patrols, © Spaarnestad Fotoarchief Cover design: Mesika Design, Hilversum Layout: PROgrafici, Goes isbn-10 90 5356 818 2 isbn-13 978 90 5356 8187 nur 689 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2006 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 5 Table of Contents List of Tables, Maps and Illustrations / 9 Acknowledgements / 11 Preface by Piet de Rooij / 13 Introduction: The War Knocked on Our Door, It Did Not Step Inside: / 17 The Netherlands and the Great War Chapter 1: A Nation Too Small to Commit Great Stupidities: / 23 The Netherlands and Neutrality The Allure of Neutrality / 26 The Cornerstone of Northwest Europe / 30 Dutch Neutrality During the Great War / 35 Chapter 2: A Pack of Lions: The Dutch Armed Forces / 39 Strategies for Defending of the Indefensible / 39 Having to Do One’s Duty: Conscription / 41 Not True Reserves? Landweer and Landstorm Troops / 43 Few -

Modernist Heritage Conservation: an Evaluation of Theories and Current Practice

Modernist Heritage Conservation: An Evaluation of Theories and Current Practice Gaia Ileana Carla ZAMBURLINI School of the Built Environment College of Science and Technology University of Salford - UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, April 2016 Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................... II LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................. VII ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................ IX ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................... X ABSTRACT ……………………………………………………………………………………………................XIII PREFACE ....................................................................................................................... XIV RATIONALE .................................................................................................................... XIV METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................................. XVI AIM ............................................................................................................................... XXII OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................. XXII RESEARCH -

Ontgonnen Verleden

Ontgonnen Verleden Regiobeschrijvingen provincie Noord-Brabant Adriaan Haartsen Directie Kennis, juni 2009 © 2009 Directie Kennis, Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuur en Voedselkwaliteit Rapport DK nr. 2009/dk116-K Ede, 2009 Teksten mogen alleen worden overgenomen met bronvermelding. Deze uitgave kan schriftelijk of per e-mail worden besteld bij de directie Kennis onder vermelding van code 2009/dk116-K en het aantal exemplaren. Oplage 50 exemplaren Auteur Bureau Lantschap Samenstelling Eduard van Beusekom, Bart Looise, Annette Gravendeel, Janny Beumer Ontwerp omslag Cor Kruft Druk Ministerie van LNV, directie IFZ/Bedrijfsuitgeverij Productie Directie Kennis Bedrijfsvoering/Publicatiezaken Bezoekadres : Horapark, Bennekomseweg 41 Postadres : Postbus 482, 6710 BL Ede Telefoon : 0318 822500 Fax : 0318 822550 E-mail : [email protected] Voorwoord In de deelrapporten van de studie Ontgonnen Verleden dwaalt u door de historisch- geografische catacomben van de twaalf provincies in Nederland. Dat klinkt duister en kil en riekt naar spinnenwebben en vochtig beschimmelde hoekjes. Maar dat pakt anders uit. Deze uitgave, samengesteld uit twaalf delen, biedt de meer dan gemiddeld geïnteresseerde, verhelderende kaartjes, duidelijke teksten en foto’s van de historisch- geografische regio’s van Nederland. Zo geeft het een compleet beeld van Nederland anno toen, nu en de tijd die daar tussen zit. De hoofdstukken over de deelgebieden/regio’s schetsen in het kort een karakteristiek per gebied. De cultuurhistorische blikvangers worden gepresenteerd. Voor de fijnproevers volgt hierna een nadere uiteenzetting. De ontwikkeling van het landschap, de bodem en het reliëf, en de bewoningsgeschiedenis worden in beeld gebracht. Het gaat over de ligging van dorpen en steden, de verkavelingsvormen in het agrarisch land, de loop van wegen, kanalen en spoorlijnen, dijkenpatronen, waterlopen, defensielinies met fortificaties. -

Must-Sees and Icons of the City 2018

Cover: Markthal, Iris van den Broek van Markthal, Iris Cover: Must-sees and icons of the city 2018 Claire Droppert 1 Rotterdam Centraal Rotterdam Central Station (Team CS, 2014) is one of the most iconic architectural sites MUST DO! in Rotterdam. The roof over the tracks is Need time to take covered in solar panels and the striking hall in this architectural roof points towards the city centre. A number masterpiece? Relax of historic elements from the former station with a cup of coffee building (1957) by Sybold van Ravesteyn next door at Engels have been re-used, like the original clock restaurant, or take in the front façade and the letters spelling the lift in the Groot out ‘Centraal Station’. In the main hall you Handelsgebouw to the 7th floor for a can find several shops, information about beautiful view of public transport and the Rotterdam Tourist Rotterdam Central Information. If you’re looking for original Station. souvenirs, don’t miss shopping at ‘Love Rotterdam. Gifts, Food & More.’ 2 Markthal You’ll find an indoor market hall in various world-class cities, but the combination with luxury housing makes Rotterdam’s Market Hall (MVRDV & INBO, 2014) the first of its kind. The apartments are arched over the DID YOU KNOW? food market in a horseshoe configuration. One of the country’s The main hall houses the market itself, as biggest outdoor well as shops, various restaurants and a four- markets is held on storey car park situated below. Look up to the large square enjoy the massive artwork sprawled across (Binnenrotte) in front of the Markthal the ceiling: the ‘Horn of Plenty’. -

Gelderse Gaten De Voortgang Van Gelderse Gemeenten Met Het Behalen Van De Doelen Uit Het Gelders Energie Akkoord

notitie Gelderse Gaten De voortgang van Gelderse gemeenten met het behalen van de doelen uit het Gelders Energie Akkoord datum auteurs maart 2018 Sem Oxenaar Derk Loorbach Chris Roorda Gelderse Gaten De voortgang van Gelderse gemeenten met het behalen van de doelen uit het Gelders Energie Akkoord auteurs Sem Oxenaar Derk Loorbach Chris Roorda over DRIFT Het Dutch Research Institute for Sustainability Transitions (DRIFT) is een toonaangevend onderzoeksinstituut op het gebied van duurzaamheidstransities. DRIFT staat (inter)nationaal bekend om haar unieke focus op transitiemanagement, een aanpak waarbij wetenschappelijke inzichten over transities door middel van toegepast actie-onderzoek worden vertaald in praktische handvatten en sturingsinstrumenten. Inhoud 1. Achtergrond 3 1.1. Opdracht 3 1.2. Opzet 3 1.3. Data 3 2. Waar staan gemeenten nu? 5 2.1. Energie praktijk 5 3. Tien gemeenten nader bekeken 11 3.1. Wat gebeurt er? 11 3.2. Wat valt op? 12 4. Lessen om te versnellen 13 4.1. Opgehaalde lessen 13 4.2. Vanuit Drift 13 4.3. Discussie 14 4.4. Dicht de Gelderse Gaten 15 5. Bijlagen 16 5.1. Bijlage 1: Kanttekeningen 16 5.2. Bijlage 2: Beschrijving 10 gemeenten 16 P. 2 1. Achtergrond 1.1. Opdracht DRIFT is gevraagd om vanuit transitieperspectief te reflecteren op de voortgang van gemeenten bij het behalen van doelen van het Gelders Energie Akkoord (GEA), en om hier conclusies en concrete aanbevelingen aan te verbinden. Centraal staan de hoofddoelen uit het akkoord, waaraan de gemeenten zich gecommitteerd hebben: → Een besparing in het totaal energieverbruik van 1,5% per jaar → Een toename van het aandeel hernieuwbare energieopwekking naar 14% van het totale verbruik in 2020 en 16% in 2023 → Klimaatneutraal in 2050 1.2. -

Reisgids 2020-2021 Chili Panama Peru Cuba Argentinië Bolivië Brazilië Suriname • REISGIDS 2020-2021 Noo Rd Groenland -At Lan Tis Ch E O Z Ce U Aa Id N -A Tla

reisgids 2020-2021 reisgids Kleine personen groepen 8 tot van 16 © johan van cutsem www.oogenblik.be cutsem van johan © HOBO • BEGELEIDE WERELDREIZEN • REISGIDS 2020-2021 Bondgenotenlaan 165 3000 Leuven e-mail [email protected] website www.hoboreizen.be Een overzicht van onze bestemmingen tel. 016 20 80 47 Jszee Noordelijke I Groenland Alaska IJsland Faroer Eilanden Canada n a a e c Kazachstan O e Mongolië h c Georgië is Oezbekistan t Noord-Korea n Armenië Kirgizstan Verenigde Staten a l Tibet Zuid-Korea t Libanon Japan A China an - Marokko Iran ea d c r Bhutan O o le Jordanië il o Nepal t Taiwan S Cuba N India Mexico Oman Laos Honduras Myanmar Guatemala Vietnam Panama Costa Rica Suriname Ethiopië Cambodja St Colombia Oeganda Sri Lanka ill Sulawesi e O Kenia Borneo cea Ecuador an Tanzania In n Peru Brazilië dische Oceaa Java/Bali Zambia Bolivië n Zimbabwe a a e Namibië Botswana Madagaskar c Australië O e h c Zuid-Afrika is Chili t Argentinië n la t Nieuw-Zeeland -A d ui Z www.hoboreizen.be VOORWOORD Waarde wereldreiziger, 32 jaar Hobo Wie het reisvirus eens te pakken heeft raakt nooit meer genezen. Met Hobo reizen kan u het virus de baas! In onze brochures wereldreizen en Europareizen vindt u ongetwijfeld een aangepaste remedie tussen de tientallen bestemmingen. Al meer dan 30 jaar bieden wij de fervente reiziger een hele reeks klassiekers aan zoals Peru, Canada, de Verenigde Staten en Zuid-Afrika, reizen die vroeg in het seizoen al het bordje uitverkocht opgespeld krijgen. Hobo reizen was in het verleden dikwijls de pionier van minder voor de hand liggende bestemmingen zoals Noord-Korea, Mongolië en Vietnam. -

Indeling Van Nederland in 40 COROP-Gebieden Gemeentelijke Indeling Van Nederland Op 1 Januari 2019

Indeling van Nederland in 40 COROP-gebieden Gemeentelijke indeling van Nederland op 1 januari 2019 Legenda COROP-grens Het Hogeland Schiermonnikoog Gemeentegrens Ameland Woonkern Terschelling Het Hogeland 02 Noardeast-Fryslân Loppersum Appingedam Delfzijl Dantumadiel 03 Achtkarspelen Vlieland Waadhoeke 04 Westerkwartier GRONINGEN Midden-Groningen Oldambt Tytsjerksteradiel Harlingen LEEUWARDEN Smallingerland Veendam Westerwolde Noordenveld Tynaarlo Pekela Texel Opsterland Súdwest-Fryslân 01 06 Assen Aa en Hunze Stadskanaal Ooststellingwerf 05 07 Heerenveen Den Helder Borger-Odoorn De Fryske Marren Weststellingwerf Midden-Drenthe Hollands Westerveld Kroon Schagen 08 18 Steenwijkerland EMMEN 09 Coevorden Hoogeveen Medemblik Enkhuizen Opmeer Noordoostpolder Langedijk Stede Broec Meppel Heerhugowaard Bergen Drechterland Urk De Wolden Hoorn Koggenland 19 Staphorst Heiloo ALKMAAR Zwartewaterland Hardenberg Castricum Beemster Kampen 10 Edam- Volendam Uitgeest 40 ZWOLLE Ommen Heemskerk Dalfsen Wormerland Purmerend Dronten Beverwijk Lelystad 22 Hattem ZAANSTAD Twenterand 20 Oostzaan Waterland Oldebroek Velsen Landsmeer Tubbergen Bloemendaal Elburg Heerde Dinkelland Raalte 21 HAARLEM AMSTERDAM Zandvoort ALMERE Hellendoorn Almelo Heemstede Zeewolde Wierden 23 Diemen Harderwijk Nunspeet Olst- Wijhe 11 Losser Epe Borne HAARLEMMERMEER Gooise Oldenzaal Weesp Hillegom Meren Rijssen-Holten Ouder- Amstel Huizen Ermelo Amstelveen Blaricum Noordwijk Deventer 12 Hengelo Lisse Aalsmeer 24 Eemnes Laren Putten 25 Uithoorn Wijdemeren Bunschoten Hof van Voorst Teylingen -

Toespraak Commissaris Van De Koning Beediging Burgemeester

1: N.B.: De uitgesproken toespraak kan afwijken van deze tekst. Meneer Van Maaren, mevrouw Van Maaren, kinderen, leden van de raad, leden van het college, dames en heren, Meneer Van Maaren, u bent niet de eerste burgemeester die ik mag beëdigen als commissaris van de Koning. Maar u bent wel de eerste burgemeester van wie ik de gehele benoemingsprocedure - van begin tot eind - zelf heb ‘gedaan’. Van de profielschetsvergadering op 28 maart, tot uw beëdiging en installatie vandaag. Daarom begin ik graag met een woord van dank aan de leden van de vertrouwenscommissie. Ik wil u complimenteren en danken voor de prettige en zorgvuldige manier waarop we dit benoemingsproces met elkaar hebben doorlopen. De heer Rehwinkel ben ik zeer erkentelijk voor de wijze waarop hij de afgelopen tweeënhalf jaar waarnemend burgemeester in Zaltbommel is geweest. In de profielschetsvergadering heb ik de fracties gevraagd in één woord te benoemen wat zij de belangrijkste kwaliteit voor de nieuwe burgemeester vonden. Dat was gemakkelijker gevraagd dan gedaan, want politici zitten doorgaans niet om woorden verlegen. Ik heb toen genoteerd: een échte bestuurder, iemand met levenservaring, stevig en betrouwbaar, ondernemend, mensgericht en daadkrachtig, Toespraak bij beëdiging burgemeester Zaltbommel, Pieter van Maaren, 19 september 2019 2: verbindend en empathisch, authentiek, communicatief en een stevige persoonlijkheid. Een mooi palet aan kwaliteiten, waar ik er graag nog één aan toevoeg: integer. Goed voorgaan doet goed volgen. In de Gemeentewet is vastgelegd dat de burgemeester de hoeder van de bestuurlijke integriteit is. Dertig kandidaten solliciteerden naar het burgemeesterschap van de gemeente Zaltbommel. De vertrouwenscommissie zag in u, meneer Van Maaren, de persoon die het best tegemoet kwam aan de profielschets. -

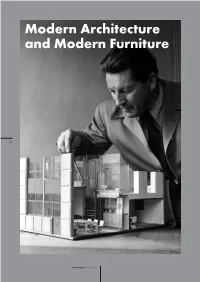

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture 14 docomomo 46 — 2012/1 docomomo46.indd 14 25/07/12 11:13 odern architecture and Modern furniture originated almost during the same period of time. Modern architects needed furniture compatible with their architecture and because Mit was not available on the market, architects had to design it themselves. This does not only apply for the period between 1920 and 1940, as other ambitious architectures had tried be- fore to present their buildings as a unit both on the inside and on the outside. For example one can think of projects by Berlage, Gaudí, Mackintosh or Horta or the architectures of Czech Cubism and the Amsterdam School. This phenomenon originated in the 19th century and the furniture designs were usually developed for the architect’s own building designs and later offered to the broader consumer market, sometimes through specialized companies. This is the reason for which an agree- ment between the architect and the commissioner was needed, something which was not always taken for granted. By Otakar M á c ˆe l he museum of Czech Cubism has its headquarters designed to fit in the interior, but a previous epitome of De in the Villa Bauer in Liboˇrice, a building designed Stijl principles that culminated in the Schröderhuis. Tby the leading Cubist architect Jiˆrí Gocˆár between The chair was there before the architecture, which 1912 and 1914. In this period Gocˆár also designed Cub- was not so surprising because Rietveld was an interior ist furniture. Currently the museum exhibits the furniture designer. The same can be said about the “father” of from this period, which is not actually from the Villa Bauer Modern functional design, Marcel Breuer. -

Tiel NIJMEGEN Oss ARNHEM Wageningen Zaltbommel

Fietsroutenetwerk Noordoost-Brabant en Rivierenland In Noordoost-Brabant vindt u veel afwisselend natuurschoon en het gebied is uitstekend geschikt om te verkennen met de U bepaalt zelf uw route en het aantal kilometers dat u wilt fietsen. U kunt in twee richtingen fietsen, van knooppunt naar fiets of te voet. Van Lith tot aan Grave kunt u vanaf de dijk genieten van de prachtige uitzichten over de Maas. Een stukje Veer Informatie knooppunt, via (wit-groene) borden. Op elk knooppunt vindt u een handig informatiepaneel, waarop u kunt zien waar u zich op zuidelijker ligt het natuurgebied De Maashorst en Herpenduin, met een oppervlakte van maar liefst 4000 ha één van de Westbroek Amersfoort Kootwijkerbroek AarkanaaNoordeindel Achterwetering dat moment bevindt. Ontbrekende bordjes in Noordoost-Brabant kunt u doorgeven op www.routesinbrabant.nl, in Rivierenland grootste aaneengesloten natuurgebieden van Brabant. Bos, heide en cultuurgrond worden hier afgewisseld met stuifduinen, Kockengen Soestduinen Harskamp Maarssen www.uiterwaarde.nlMusschendorp op www.uiterwaarde.nl beekdalen en vennen. Zutphen Download de gratis overzetveren app! Barneveldsche Beek Aarlanderveen Maarssenbroek Bilthoven Wandel of struin eens ‘AndersBarnevel langsd de Maas’ Cultuur A Hoven Nieuwe Wetering Bilthoven Den Dolder Leusden-Centrum Liniepont (over de Lek) Vlasakkers Achterveld Heerlijk uitwaaien langs de Maas in de zomer en winter! Het ‘Anders langs de Maas’-struinpad staat garant voor urenlang wandel- Op zoek naar culturele uitstapjes in Rivierenland, bezoek www.rivierenland.nl voor een volledig overzicht. In Noordoost- Vaartijden: zomerdienst. Zuidhoek Teckop Leusden April t/m september volgens vaarschema. Maarn Laagnieuwkoop N230 plezier. Deze middellange afstandsroute tussen ‘s-Hertogenbosch en Cuijk van circa 70 km kent een zomer- én wintertraject, BrabantHarsk maaktamp u kennis met de eeuwenoude vestingstadjes Megen, Ravenstein en Grave. -

Manifestasi Budaya Indis Dalam Arsitektur Dan Tata Kota Semarang Pada Tahun 1900 - 1950

MANIFESTASI BUDAYA INDIS DALAM ARSITEKTUR DAN TATA KOTA SEMARANG PADA TAHUN 1900 - 1950 SKRIPSI Diajukan Untuk Melengkapi Persyaratan Guna Mencapai Gelar Sarjana Sastra Jurusan Ilmu Sejarah Fakultas Sastra Dan Seni Rupa Universitas Sebelas Maret Surakarta Disusun Oleh : T R I P A R T O N O C 0 5 0 5 0 0 3 F A K U L T A S S A S T R A D A N S E N I R U P A UNIVERSITAS NEGERI SEBELAS MARET S U R A K A R T A 2 0 1 0 i HALAMAN PERSETUJUAN MANIFESTASI BUDAYA INDIS DALAM ARSITEKTUR DAN TATA KOTA SEMARANG PADA TAHUN 1900 - 1950 Disusun Oleh : T R I P A R T O N O C 0 5 0 5 0 0 3 Telah Disetujui oleh Pembimbing Tiwuk Kusuma H, S.S. M.Hum NIP. 197306132000032002 Mengetahui Ketua Jurusan Ilmu Sejarah Dra. Sri Wahyuningsih, M.Hum NIP. 19540223198601200 ii HALAMAN PENGESAHAN Disusun Oleh : T R I P A R T O N O C 0 5 0 5 0 0 3 Telah disetujui oleh Tim Penguji Skripsi Fakultas Sastra Dan Seni Rupa Universitas Sebelas Maret Pada Tanggal ..... ................ 2010 Jabatan Nama Tanda Tangan Drs. Warto, M. Pd Ketua NIP. 196109251986031001 (………………) Dra. Hj. Isnaini W. W, M. Pd Sekretaris NIP. 195905091985032001 (………………) Tiwuk Kusuma H, S.S. M.Hum Penguji I NIP. 197306132000032002 (………………) Drs. Soedarmono, SU Penguji II NIP. 194908131980031001 (………………) Dekan Fakultas Sastra Dan Seni Rupa Universitas Sebelas Maret Drs. Sudarno, M.A NIP. 195303141985061001 iii PERNYATAAN Nama : TRI PARTONO Nim : C 0505003 Menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa skripsi berjudul “Manifestasi Budaya Indis dalam Arsitektur dan Tata Kota Semarang Pada Tahun 1900-1950” adalah betul-betul karya sendiri, bukan dari plagiat dan tidak dibuat oleh orang lain.