University of Oklahoma Graduate College Language Ideologies and Practices Among University Learners of Native American Langua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborating for Prosperity with American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities

Collaborating for Prosperity With American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities USDA Rural Development Innovation Center Together, America Prospers From 2001 to 2018 USDA Rural Development invested more than $6.2 billion in Indian Country and Alaska. USDA Rural Development places a high value on its relationship with Tribes, American Indians, and Alaska Natives. We are committed to increasing investment throughout Indian Country and Alaska. We are collaborating and partnering with Tribes to realize a brighter future for families, children, and Tribal communities. Through loans, grants, and technical assistance, Rural Development makes critical investments in infrastructure, schools, health clinics, housing, and businesses, to benefit Native families and communities across rural America. Rural Development supports American Indians and Alaska Natives in holistic, sustainable, and culturally responsive ways. Every Tribal Nation has unique assets and faces distinct challenges. Maximizing the potential of these assets, and addressing local challenges, can only happen in an environment where relationships and trust provide a foundation for true partnership and collaboration. Rural Development staff understand that the legal, regulatory, governmental structure, protocols, and culture are unique to each Tribal Nation. We recognize that Tribes are distinct. We strive to understand those distinctions and tailor the delivery of services to be responsive to each Tribe’s circumstances -

71-28823 BADGER, Herbert Andrew, 1935- A

71-28,823 BADGER, Herbert Andrew, 1935- A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW. University of Southern Mississippi, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, linguistics University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHT BY HERBERT ANDREW BADGER 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. University of Southern Mississippi A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW by Herbert Andrew Badger A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: Director Dean of tfte Graduate School May, 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract A DESCRIPTIVE GRAMMAR OF MISSISSIPPI CHOCTAW by Herbert Andrew Badger May, 1971 The justification for a grammar of Mississippi Choctaw is contingent upon two factors. First, the forced removal of the Choctaws to Oklahoma following the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek had important linguistic effects, for while the larger part of the Choctaws removed to the West where their language probably followed its natural course, there remained in Mississippi a relatively small segment of Choctaws who, because they were fugitives from the removal, were fragmented into small, isolated bands. Thus, communication between the two groups and between the isolated bands of Mississippi Choctaws was extremely limited, resulting in a significant difference between the languages of the two groups. Second, the only grammar of Choctaw, Cyrus Byington's early nineteenth cen tury Grammar of the Choctaw Language, is inadequate because it was written before descriptive linguistic science was formalized, because it reflected the Choctaw language just 1 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Sacred Rain Arrow: Honoring the Native American Heritage of the States While Balancing the Citizens' Constitutional Rights Amelia Coates

American Indian Law Review Volume 38 | Number 2 1-1-2014 Sacred Rain Arrow: Honoring the Native American Heritage of the States While Balancing the Citizens' Constitutional Rights Amelia Coates Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Amelia Coates, Sacred Rain Arrow: Honoring the Native American Heritage of the States While Balancing the Citizens' Constitutional Rights, 38 Am. Indian L. Rev. 501 (2014), http://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol38/iss2/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT SACRED RAIN ARROW: HONORING THE NATIVE AMERICAN HERITAGE OF THE STATES WHILE BALANCING THE CITIZENS’ CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS Amelia Coates* Abstract Many states’ histories and traditions are steeped heavily in Native American culture, which explains why tribal imagery and symbolism are prevalent in official state paraphernalia such as license plates, flags, and state seals. Problems arise for states using Native American artwork when a citizen takes offense to the religious implications of Native American depictions, and objects to having it displayed on any number of items. This Comment will examine the likely outcome of cases involving Establishment Clause and compelled speech claims arising from Native American images and propose a solution for balancing the constitutional rights of the citizens while still honoring the states’ rich Native American heritage. -

Chahta Anumpa: a Multimodal Corpus of the Choctaw Language

Chahta Anumpa: A Multimodal Corpus of the Choctaw Language Jacqueline Brixey, Eli Pincus, Ron Artstein USC Institute for Creative Technologies 12015 E Waterfront Dr, Los Angeles, CA 90094 {brixey, pincus, artstein}@ict.usc.edu Abstract This paper presents a general use corpus for the Native American indigenous language Choctaw. The corpus contains audio, video, and text resources, with many texts also translated in English. The Oklahoma Choctaw and the Mississippi Choctaw variants of the language are represented in the corpus. The data set provides documentation support for the threatened language, and allows researchers and language teachers access to a diverse collection of resources. Keywords: endangered languages, indigenous language, multimodal, Choctaw, Native American languages 1. Introduction not abundant. The goal of this database is thus to first pre- This paper introduces a general use corpus for Choctaw, an serve a threatened language. The second contribution is to American indigenous language. The Choctaw language is compile a comprehensive data set of existing resources for spoken by the Choctaw tribe, who originally inhabited the novel research opportunities in history, linguistics, and nat- southeastern United States. The tribe is the fourth largest ural language processing. The final contribution is to pro- indigenous group by population in the United States with vide documentation of the language for language learners 220,000 enrolled members.1 The Choctaw language, how- and teachers, in order to assist in revitalization efforts. ever, is classified as “Threatened” by Ethnologue,2 as there are only 10,400 fluent speakers and the language is losing 2. Choctaw tribe and language users. 2.1. -

History and Civics of Oklahoma

Class- t~6^^ Book. '// /<^ (kpightl^' COPYRIGHT DEPOSIT. ( \U y d HISTORY AND CIVICS OF OKLAHOMA BY L: J: ABBOTT, LL.B, M.A. PROFESSOR OF AMERICAN HISTORY, CENTRAL STATE NORMAL SCHOOL EDMOND, OKLAHOMA GINN AND COMPANY BOSTON • NEW YORK • CHICAGO • LONDON Copyright, 1910 By L. J. ABBOTT ALL RIGHTS RESERVED GINN AND COMPANY • PRO- PRIETORS • BOSTON • U.S.A. eCU265302 5\ t HISTORY OF OKLAHOMA PREFACE While Oklahoma is the youngest of the states, yet it had a considerable population almost a generation earlier than any of the states west of those that border the Mississippi, Texas alone excepted. Here we find much the best example of a prolonged effort of the aborigines of the United States to de- velop their own civilization in their own way. The history of this effort should be of interest to every student of American institutions. How much of this civilization was due to white influence and how much can be credited to Indian initiative must be left to the judgment of the reader. One of the chief benefits of historical study is the testing of authorities. No field offers a better opportunity for this than Oklahoma history. Almost all data relating to the Indian na- tions is so interwoven with myth and fiction that it is difficult, indeed, to separate authoritative facts from endless legends and weird tales of Indian life. So while this little book is pre- sented in concise, and we trust simple, form, yet we have zealously sought to use in its preparation no source that will not bear most careful scrutiny. -

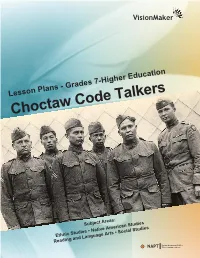

Choctaw Code Talkers

VisionMaker Lesson Plans - Grades 7-Higher Education Choctaw Code Talkers Subject Areas: Ethnic Studies • Native American Studies Reading and Language Arts • Social Studies NAPT Native American Public Telecommunications VisionMaker Procedural Notes for Educators Film Synopsis In 1918, not yet citizens of the United States, Choctaw men of the American Expeditionary Forces were asked to use their Native language as a powerful tool against the German Forces in World War I, setting a precedent for code talking as an effective military weapon and establishing them as America's original Code Talkers. A Note to Educators These lesson plans are created for students in grades 7 through higher education. Each lesson can be adapted to meet your needs. Robert S. Frazier, grandfather of Code Talker Tobias Frazier, and sheriff of Jack's Fork and Cedar Counties Image courtesy of "Choctaw Code Talkers" Native American Public 2 NAPT Telecommunications VisionMaker Objectives and Curriculum Standards a. Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, Objectives paragraph, or text; a word’s position or function in a sentence) These activities are designed to give participants as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase. learning experiences that will help them understand and b. Identify and correctly use patterns of word changes that indicate different meanings or parts of speech. consider the history of the sovereign Choctaw Nation c. Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., of Oklahoma, and its unique relationship to the United dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to States of America; specifically how that relates to the find the pronunciation of words, a word or determine or clarify documentary, Choctaw Code Talkers. -

Newsletter Xxvi:2

THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF THE INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES OF THE AMERICAS NEWSLETTER XXVI:2 July-September 2007 Published quarterly by the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Lan- SSILA BUSINESS guages of the Americas, Inc. Editor: Victor Golla, Dept. of Anthropology, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California 95521 (e-mail: golla@ ssila.org; web: www.ssila.org). ISSN 1046-4476. Copyright © 2007, The Chicago Meeting SSILA. Printed by Bug Press, Arcata, CA. The 2007-08 annual winter meeting of SSILA will be held on January 3-6, 2008 at the Palmer House (Hilton), Chicago, jointly with the 82nd Volume 26, Number 2 annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America. Also meeting concur- rently with the LSA will be the American Dialect Society, the American Name Society, and the North American Association for the History of the CONTENTS Language Sciences. The Palmer House has reserved blocks of rooms for those attending the SSILA Business . 1 2008 meeting. All guest rooms offer high speed internet, coffee makers, Correspondence . 3 hairdryers, CD players, and personalized in-room listening (suitable for Obituaries . 4 iPods). The charge for (wired) in-room high-speed internet access is $9.95 News and Announcements . 9 per 24 hours; there are no wireless connections in any of the sleeping Media Watch . 11 rooms. (The lobby and coffee shop are wireless areas; internet access costs News from Regional Groups . 12 $5.95 per hour.) The special LSA room rate (for one or two double beds) Recent Publications . 15 is $104. The Hilton reservation telephone numbers are 312-726-7500 and 1-800-HILTONS. -

Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in This Edition of Newspapers in Education

he American Indian Cultural Center and Museum (AICCM) is honored Halito! Oklahoma has a unique history that differentiates it from any other Tto present, in partnership with Newspapers In Education at The Oklahoman, state in the nation. Nowhere else in the United States can a visitor hear first the Native American Heritage educational workbook. Workbooks focus on hand-accounts from 39 different American Indian Tribal Nations regarding the cultures, histories and governments of the American Indian tribes of their journey from ancestral homelands, or discover how Native peoples have Oklahoma. The workbooks are published twice a year, around November contributed and woven their identities into the fabric of contemporary Oklahoma. and April. Each workbook is organized into four core thematic areas: Origins, Oklahoma is deeply rooted in American Indian history and heritage. We hope Native Knowledge, Community and Governance. Because it is impossible you will use this guide to explore our great state and to learn about Okla- to cover every aspect of the topics featured in each edition, we hope the Humma. (“Red People” in the Choctaw language.)–Gena Timberman, Esq., workbooks will comprehensively introduce students to a variety of new subjects and ideas. We hope you will be inspired to research and find out more information with the help of your teachers and parents as well as through your own independent research. The American Indian Cultural Center and Museum would like to give special thanks to the Oklahoma Tourism & Recreation Department for generously permitting us to share information featured in the Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in this edition of Newspapers in Education. -

The Chickasaw Nation, Muscogee Creek Nation, Sac & Fox Nation, and Choctaw Nation Present

The Chickasaw Nation, Muscogee Creek Nation, Sac & Fox Nation, and Choctaw Nation present NATIVE AMERICAN Language & Culture Newspapers for this educational program provided by: Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 List of Tribes in Oklahoma ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................4 The Chickasaw Nation ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................5-8 Sac & Fox Nation ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................9-13 Choctaw Nation ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................14-18 -

The State of Oklahoma - an Introduction to the Sooner State from NETSTATE.COM

The State of Oklahoma - An Introduction to the Sooner State from NETSTATE.COM HOME INTRO The State of Oklahoma SYMBOLS ALMANAC ore than 50 languages are spoken in ECONOMY M GEOGRAPHY the state of Oklahoma. There are 55 STATE MAPS distinct Indian tribes that make the state PEOPLE their home, and each of these tribes has GOVERNMENT its own language or dialect. The colorful FORUM history of the state includes Indians, NEWS cowboys, battles, oil discoveries, dust COOL SCHOOLS storms, settlements initiated by offers of STATE QUIZ STATE LINKS free land, and forced resettlements of BOOK STORE entire tribes. MARKETPLACE NETSTATE.STORE Oklahoma, the Sooner State Oklahoma's Indian heritage is honored in NETSTATE.MALL its official state seal and flag. At the GUESTBOOK center of the seal is a star, and within CONTACT US each of the five arms of the star are symbols representing each of the five tribes (the "Five Civilized Tribes") that House Flags were forcefully resettled into the From $5.99 territory of Oklahoma. The tribes Great Selection. depicted on the seal are the Creeks, the Unbeatable Prices. Chickasaw, the Choctaw, the Cherokee, Flags For Every and the Seminoles. The present Season & Reason. www.discountdecorati… Oklahoma state flag depicts an Indian war shield, stars, eagle feathers, and an Indian peace pipe, as well as a white Find Birth man's symbol for peace, an olive branch. Records Online THE STATE NAME: 1) Search Birth Records for Free 2) Find the Oklahoma is a word that was made up by the native American missionary Allen Records Instantly! Birth.Archives.com Wright. -

Teaching with Beyond the Centennial by Carlos Tello

Teaching with Beyond the Centennial by Carlos Tello This printer-friendly document is designed to help teachers present, discuss, and teach about Oklahoma history and art literacy through the use of this work of art. The information and exercises here will aid in understanding and learning from this artwork. Contents: • First Analysis and Criticism • Overview of the Artwork • About the Artist • Oklahoma History Details • Visual Art Details • Suggested Reading • Final Analysis • PASS Objectives Oklahoma Arts Council • Teaching with Capitol Art First Analysis and Criticism The steps below may be used for group discussion or individual written work. Before beginning the steps, take two minutes to study the artwork. Look at all the details and subject matter. After studying the artwork in silence, follow these steps: Describe: Be specific and descriptive. List only the facts about the objects in the painting or sculpture. • What things are in the artwork? • What is happening? • List what you see (people, animals, clothing, environment, objects, etc.). Analyze: • How are the elements of art – line, shape, form, texture, space, and value used? • How are the principles of design – unity, pattern, rhythm, variety, balance, emphasis, and proportion used? Interpretation: Make initial, reasonable inferences. • What do you think is happening in the artwork? • Who is doing what? • What do you think the artist is trying to say to the viewer? Evaluate: Express your opinion. • What do you think about the artwork? • Is it important? • How does it help you understand the past? • Do you like it? Why or why not? Oklahoma Arts Council • Teaching with Capitol Art Overview of the Artwork As Oklahomans reflected on our first century of statehood in 2007, members of Friends of the Capitol envisioned Oklahoma’s next 100 years. -

Subject Index To

House Journal – Index 1 GENERAL SUBJECT INDEX First Session, 48th Legislature 2001 SUBJECT INDEX ABBREVIATIONS smad ........................................... Subject matter added (where code follows) smde ........................................... Subject matter deleted (where code follows) hc ................................................ House committee hf ................................................ House floor sc ................................................ Senate committee sf ................................................. Senate floor cc ................................................ Conference committee (Boldface = Measure Enacted) A ABORTION Actions against physician, granting for failure to provide sufficient information. HB 1331, Calvey-H Breast-Cancer Act, Abortion-, creating; link information; time; restrictions; intervention. HB 1079, Coleman-H Cause of action against physician for failure to provide sufficient information prior to. HB 1267 (smad hf), Stanley-H, Cain-S Child support payment. HB 1079, Coleman-H Coercion, prohibiting. HB 1079, Coleman-H Consent, allowing withdrawal. HB 1079, Coleman-H Defining. HB 1079, Coleman-H Information, requiring. HB 1079, Coleman-H Intervention. HB 1079, Coleman-H Intrauterine cranial decompression, defining. HB 1766, Balkman-H Life threatening, allowing. HB 1079, Coleman-H Medical treatment (see Minors, Parental notification, Performing, below) Mifepristone (RU-486), prohibiting selling, prescribing, dispensing or distributing; penalties. HB 1038, Graves-H; HB 1809,